In addition to today’s resource, please see and review Links To “A Safe and Simple Algorithm for Adding and Adjusting Mealtime Insulin to Basal-Only Therapy”

Posted on January 3, 2024 by Tom Wade MD

Today, I reviewed and link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ #397: Insulin, Type 2 Diabetes, Fanny Packs, and Hypoglycemia with Dr. Jeff Colburn*.

*Valdez I, Colburn J, Williams PN, Watto MF. “#397: Insulin, Type 2 Diabetes, Fanny Packs, and Hypoglycemia with Dr. Jeff Colburn”. The Curbsiders Internal Medicine Podcast. thecurbsiders.com/category/curbsiders-podcast May 29, 2023.

All that follows is from the show notes of the above outstanding resource.

Managing the Ups and Downs of Insulin from Start to Finish in Patients Living with Type 2 Diabetes

Don’t be scared of insulin or hypoglycemia anymore! Our Kashlak Friend of the Pod Dr. Jeff Colburn gives us all the essentials you’ll need in your fanny pack for navigating the ups and downs of insulin in type 2 diabetes.

Claim free CME for this episode at curbsiders.vcuhealth.org!

Show Segments

- Intro

- Rapid fire questions/Picks of the Week

- Case #1: Starting insulin

- Types of basal insulin: glargine, detemir, NPH, 70/30 NPH/regular

- Glucose monitoring while on insulin

- Glucose targets when taking insulin

- Overbasalization

- Adding additional agents to basal insulin

- Case #2: Deescalating insulin

- Insulin use in the geriatric population

- Hypoglycemia Rule of 15

- Glucagon how-to

- Outro

Insulin, Type 2 Diabetes, Fanny Packs, and Hypoglycemia Pearls

- Starting insulin does not mean the patient failed to do what they were supposed to do, but instead it means their beta cells are failing to do what they’re supposed to do

- Insulin could be started when other treatments are cost-prohibitive or if the HbA1c is over 10%

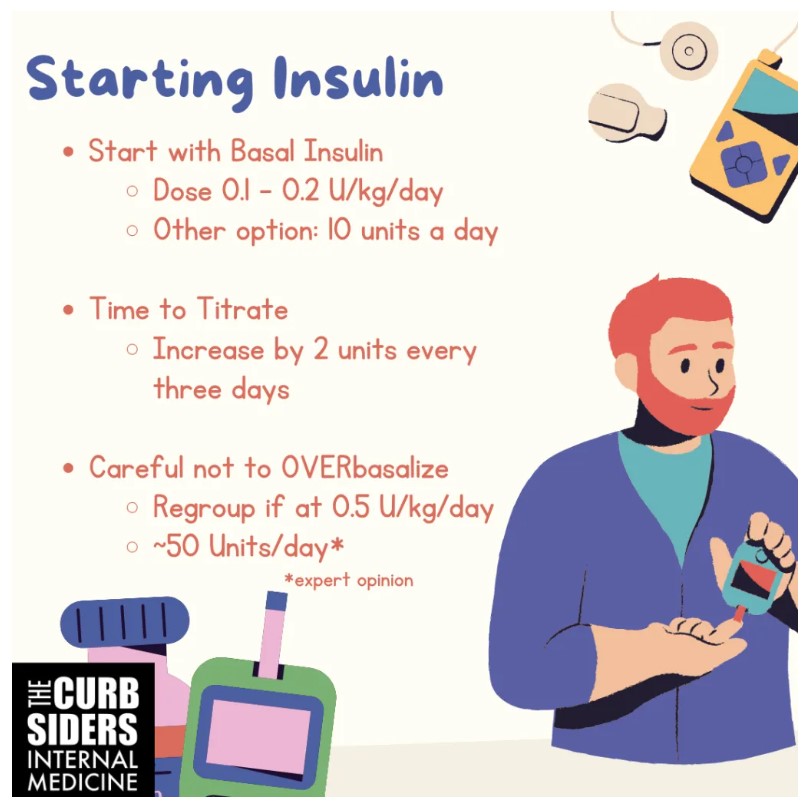

- Start basal insulin at 0.1U – 0.2U/kg/day or at 10U/day and increase basal insulin by 2 units every three days until morning fasting glucose is consistently 90 to 130 mg/dl

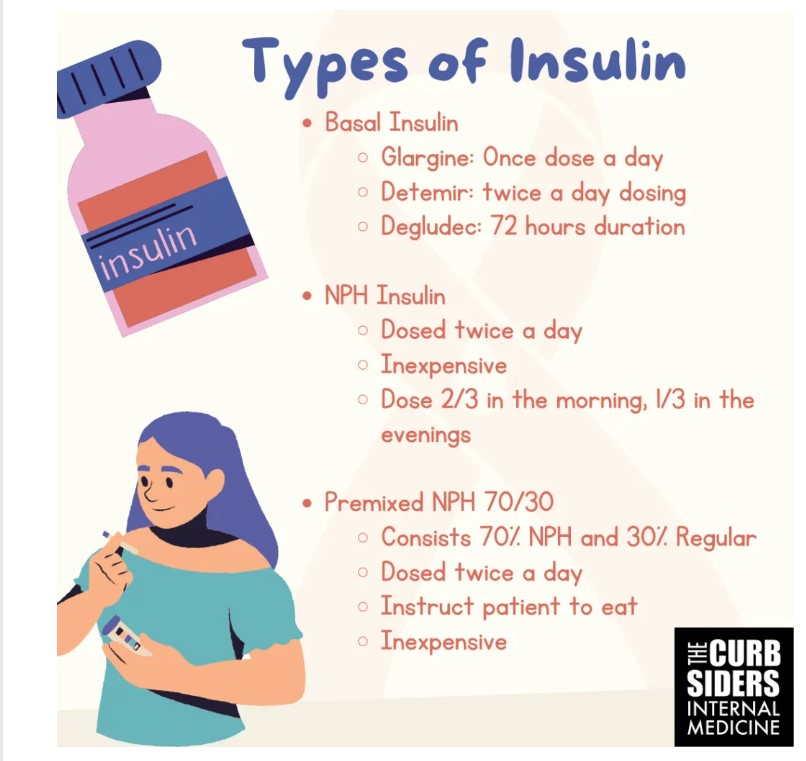

- NPH and pre-mixed insulin should be dosed twice a day with two-thirds of the insulin during the day and one-third in the afternoon/evening.

- It is OK to dose basal insulin in the morning; determir is a basal insulin that should be dosed twice a day.

- In the US, big box retailers have $25 regular and NPH insulin available to patients when cost is an issue (google where to find)

- Recognize overbasalization; suspect it if the patient is using ~50 units of basal insulin a day or ~0.5U/kg/day; review the daily blood sugar patterns with the patient to adjust basal insulin or add another agent

- Decrease basal insulin when adding other agents such as mealtime insulin, GLP-1 RA, or SGLT2-1.

- Mealtime insulin doses should approximately total the basal insulin in patients that approach absolute insulin deficiency and require complete replacement of insulin

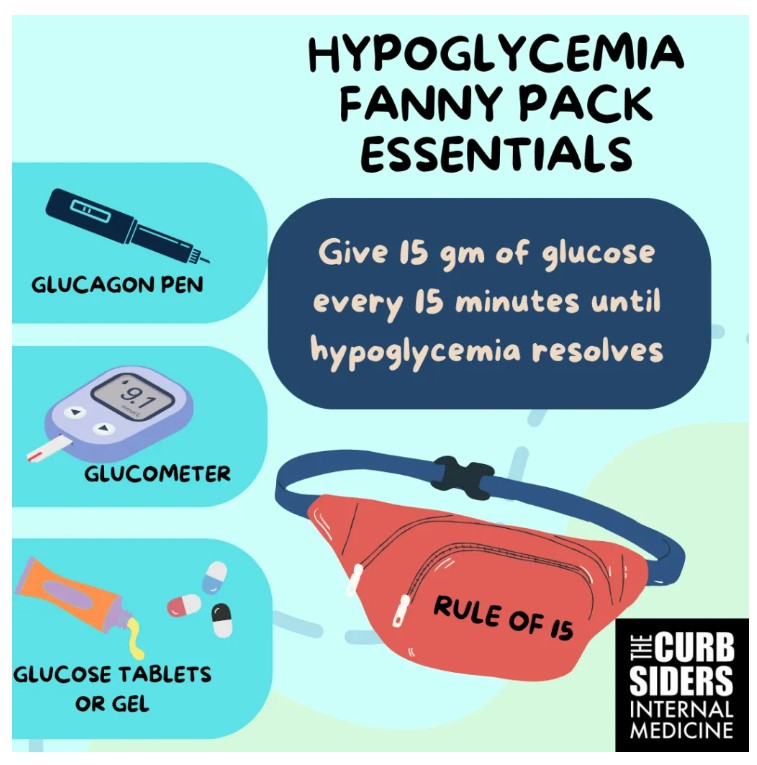

- The Rule of 15 for hypoglycemia: Teach patients and caregivers to identify hypoglycemia and treat it with 15gm of glucose every 15 minutes until corrected. Prescribe glucagon to patients starting multiple daily insulin injections (they are at higher risk of hypoglycemia)

When Insulin is the Right Call

Half of the beta cells have lost their function in type 2 diabetes by the time of diagnosis (UK Prospective Diabetes Study 16, 1996). Current guidelines published by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend starting with non-insulin agents such as GLP-1 RA or SGLT2-i, however insulin can be initiated in a patient with HbA1c above 10% to achieve more rapid glycemic control.

It’s not you, it’s the Beta-Cell

Dr. Colburn reflects on patient concerns about insulin initiation– they may have resistance to starting insulin, because they have seen friends or family start insulin and shortly after experience a diabetic complication (such as amputation or dialysis), which they see as cause and effect. It is important to address such misconceptions, and explain that long-accumulating microvascular complications were the cause of the complication, not insulin itself.

Recently published guidelines emphasize the need to steer away from framing insulin as a threat or punishment. Dr. Colburn says that a patient starts insulin not because they failed, but because their beta cells have failed them. Fat deposits in the pancreas decrease beta-cell functionality thereby reaching a threshold where only insulin will be an effective therapy (Inashi and Saisho, 2020).

Starting Insulin: Are we there yet?

Per ADA guidelines (ElSayed et al, 2023; Section 9), insulin should be started when a patient with type 2 diabetes has severe hyperglycemia with catabolic symptoms (e.g. glycosuria, ketosis) or when the HbA1c is above 10%. Additionally, insulin could be started when glucose control does not improve with non-insulin treatments, such as metformin, GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2 inhibitors, or if these treatments are cost-prohibitive. It is important to remember that insulin can cause weight gain because it creates a state of over-insulinization from lagging in the subcutaneous tissue. Decreasing the dose of insulin while on other treatments should help mitigate weight gain (and many of these newer agents help with weight loss).

Step One: Basal Insulin

The pancreas produces approximately one unit of basal insulin per hour in an individual without insulin resistance, to match the liver’s sugar output (and more when we eat to cover food intake). To determine how much basal insulin to prescribe, the ADA guidelines recommend starting at a rate of 0.1 or 0.2 units of basal insulin per kilogram per day OR 10 units a day.

Step Two: Time to Titrate

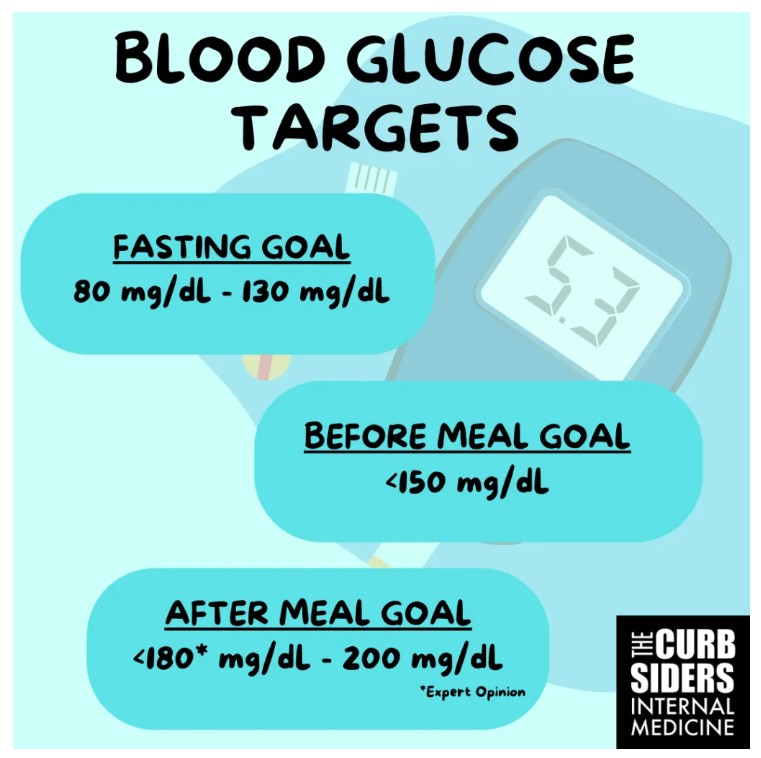

Dr. Colburn recommends that patients on insulin check am fasting blood glucose every single day. The fasting glucose goal should be between 90 to 130 mg/dL (ElSayed et al, 2023; Section 6). The ADA recommends increasing a once-daily basal insulin such as glargine by 2 units every three days until the patient meets this fasting glucose goal.

Step Three: Overbasalized? When to Stop Titrating and Regroup

Overbasalization is the titration of the basal insulin dose above what is useful for glucose management (with potential side effects of hypoglycemia and undertreatment of mealtime highs). As the patient approaches 0.5U/kg/day of basal insulin (or per Dr. Colburn, simplify the math and use 50 units a day as the upper threshold of basal insulin), they are at risk of overbasalization and it is time to connect with the patient to discuss mealtime insulin (Cowart 2020; Cowart et al 2023). At this point, mealtime insulin may be needed to address the blood sugar patterns that are not being corrected by basal insulin.

Basal Insulin: Glargine and Detemir

Glargine is one of the most common basal insulin formulations. It has an onset of 2 hours and duration of action of 24 hrs. Determir has a duration of 12 hours and was developed to be used as a twice a day basal insulin. Dr. Colburn reminds us that the same dose should be administered in each injection. Degludec has a 72 hour duration of function and does not peak. This insulin still has to be given every day but as Dr. Colburn mentions, it is more “forgiving” if the next dose is not given at the exact same time. This may be a more useful option for patients that experience low blood sugars while on glargine as can be seen in patients with type 1 diabetes, but less common in type 2 diabetes.

Premixed 70/30 Insulin

An alternative to NPH is premixed insulin which contains 70% NPH insulin and 30% regular, fast acting insulin. This insulin is also dosed twice a day and it will peak around 6 hours from when it is given. In Dr. Colburn’s experience, this insulin could be used for patients that need to use a mealtime insulin but are not able to frequently check blood sugars or give themselves frequent injections. The risk of hypoglycemia is also increased with this premixed insulin, thus Dr. Colburn warns us to ensure that patients eat when this peaks to prevent hypoglycemia (Ilag et al 2007). For example, if a patient injects this insulin in the mornings, they must have a meal around lunchtime. Assuming the patient has a larger meal that is slower to digest in the evening, the risk of nighttime hypoglycemia could be mitigated but is still present.

Sulfonylurea, Metformin and Basal Insulin

Metformin should be continued when basal insulin is started as recommended in the ADA guidelines. Sulfonylureas trigger insulin release from the beta-cells and should be given at mealtime. As part of his personal practice, Dr. Colburn reduces the sulfonylurea in half when starting basal insulin and continues at this dose unless the patient continues to have hyperglycemia. He suggests checking blood glucose before and after meals until the patient establishes a reliable and stable range of blood glucose without hypoglycemia. These readings should help determine the dosing or discontinuation of sulfonylureas while the patient is using insulin.

GLP-1 RA and Basal Insulin

Generally speaking, weekly GLP-1 RA injections take about four weeks to reach a steady state and demonstrate their impact on the blood sugars (Hinnen, 2017). Dr. Colburn recommends decreasing the basal insulin by approximately 20% to reduce the chances of hypoglycemia. It should be noted that there are fixed-ratio combination products of basal insulin with GLP-1 RA available on the market that include specific instructions to guide the patient through dosing and titration. Our expert reminds us to counsel patients on the GLP-1 RA side effects including nausea and constipation, which patients can experience even at low doses.

SGLT2-inhibitors and Basal Insulin

This class of drug can be very effective in patients with blood sugars over 180mg/dL and are less likely to trigger hypoglycemia. Even with this low risk for hypoglycemia, Dr. Colburn’s expert recommendation is to decrease the basal insulin by 10%.

Tracking Blood Glucose

Glucose monitoring is needed when the patient is taking insulin and sulfonylureas but not necessary while the patient is taking metformin, SLGT2-i or GLP-1 RA (ElSayed et al, 2023; Section 7). The fasting morning blood glucose is the most important number to follow because it will inform adjustments made to the basal insulin dose. The recommended fasting blood glucose goal is 90 mg/dL to 130 mg/dL.

Similarly, blood glucose monitoring is needed before administering mealtime insulin, as the reading may affect the amount of meal-time insulin needed.* While we didn’t get into the details of correctional insulin in this episode, Dr. Colburn gave an example of lowering the dose of pre-meal insulin if a patient has a blood glucose level at or below 70 mg/dL to prevent hypoglycemia or adding insulin (a correction scale) if the pre-meal blood glucose is quite high.

*See A Safe and Simple Algorithm for Adding and Adjusting Mealtime Insulin to Basal-Only Therapy. Corresponding author: Mary L. Johnson, Mary.L.Johnson@ParkNicollet.com Clin Diabetes 2022;40(4):489–497 https://doi.org/10.2337/cd21-0137 PubMed: 36381310

The Colburn Approach to Pattern Management ™

Dr. Colburn’s practice is to get a sense of the patient’s blood glucose pattern based on their lifestyle and adjust treatment with the following approach.

- Detect the Pattern:

- For a few days ahead of a follow-up visit with him, he asks patients to track their fasting blood sugars and at bedtime as well as before and after different meals each day, such as breakfast on one day and lunch and dinner on other days. This practice allows him and the patient to detect a pattern of high and low blood sugars.

- Fix the Lows

- He investigates the why behind the low blood sugars and if there is no discernible cause for low sugars (ie: skipped meals, over-exertion, etc), he reduces the basal insulin dose.

- Fix the Highs

- If the high blood sugars occur around meals, he recommends adding mealtime insulin if other agents such as GLP-1 RA or SGLT2-inhibitors are not available.

- If mealtime insulin is needed, ease the patient into using it once a day with the largest meal. The ADA guidelines suggest starting 4-6 units of mealtime insulin with the biggest meal of the day and reducing the basal insulin dose by approximately the same amount.

- As the need for mealtime insulin increases, the total amount of mealtime insulin should equal the amount of basal insulin the patient is using; for example, if the patient is using 30U of basal insulin, the total of mealtime insulin should equal 30U divided by the number of meals.

Less is More in the Older Adult Patient

Deintensify insulin treatment in geriatric patients with multimorbidity and impaired “constitutional health”, to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia (ElSayed et al, 2023; Section 13). Insulin demands drop as patients eat less and lose muscle mass which can happen in anyone but occurs more often with aging (Won Park et al 2006). Additionally, the effect of insulin increases as it lingers longer in patients as kidney function declines. Dr. Colburn’s routine approach for older adults is to decrease insulin by 10% to 20% depending on the degree of hypoglycemia. If compliance with nighttime basal insulin is an issue, the ADA guidelines suggest dosing basal insulin in the mornings. Mealtime bolus doses should be adjusted or even skipped depending on the patient’s diet such as meal frequency or portion sizes (Munshi et al, 2016; Jude et al 2022). Dr. Colburn cautions about the use of GLP-1 RA in geriatric patients; using these agents in severe CKD (GFR <15) is off-label and the side effects could worsen existing conditions such as frailty and weight loss.

The Hypoglycemia Rule of 15 Fanny Pack Essentials

Planning for hypoglycemia is a critical part of starting insulin! Encourage patients and their caregivers to be familiar with how to identify and treat hypoglycemia. They should be equipped to identify hypoglycemia symptoms (hunger, anxiety, or sweating), carry a glucose monitoring device (hypoglycemia is blood glucose under 70 mg/dL), and carry a glucose treatment (glucose tabs, gel and glucagon). Once hypoglycemia is identified, it should be treated with 15 grams of glucose such as three or four over-the-counter glucose tablets or glucose gels that can be squeezed into the inside of the patient’s cheek (ElSayed et al, 2023; Section 6). After 15 minutes from dosing with glucose tablets or gel, recheck the patient’s blood sugar to ensure it is no longer in the range of hypoglycemia, otherwise you should repeat the treatment. Emergency services should be contacted if there is no improvement after several attempts.

Glucagon to the Rescue

Dr. Colburn suggests prescribing glucagon injections or intranasal powders to patients who use insulin, and instruct patients to carry this with them. Patients and caregivers should be taught how to administer glucagon since the injection has to be reconstituted. Because glucagon stimulates the liver to release its glycogen reserve, it can only be used once a day and the patient should be advised to resume their normal eating schedule to build up their hepatic glycogen reserve (Boido et al, 2014). The most common side effect after using glucagon is nausea or vomiting so patients should be placed on their side in a recovery position to reduce the risk of aspiration.

Take-Home Points

- Insulin is used because the beta-cells have failed, not because the patient failed

- Basal insulin is a useful, powerful medicine; do not be afraid to use it

- Metformin and other non-insulin medications might be able to stall the loss of beta-cell function while helping with weight loss

- Start basal insulin at a dose of 0.1 to 0.2 units/kg/day until your patient achieves a fasting glucose between 90mg/dL to 130mg/dL

- Easily titrate up on basal insulin by increasing the dose by 2 units every three days until the patient reaches their target.

- Pair hypoglycemia teaching with the Rule of 15 when starting a patient on insulin

- Don’t be afraid of insulin!

Links

- ADA Standards of Care in Diabetes – 2023 App

- American Diabetes Association Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Practice Guidelines -202

- #387 Diabetes Updates 2023 New Tools for the New Rules

- #296 Diabetes FAQ 2021 with Dr. Jeff Colburn

- #168 Diabetes Update 2019 with Dr Jeff Colburn