Please see also Links To And Excerpts From “Ovarian Torsion Myths” And “Ovarian Torsion Imaging” From EMC

Posted on April 24, 2020 by Tom Wade MD

In this post I link to and excerpt from Adnexal Torsion in Adolescents from ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 783, August 2019.

Here are excerpts:

Abstract:

Adnexal torsion is the fifth most common gynecologic emergency. The most common ovarian pathologies found in adolescents with adnexal torsion are benign functional ovarian cysts and benign teratomas. Torsion of malignant ovarian masses in this population is rare. In contrast to adnexal torsion in adults, adnexal torsion in pediatric and adolescent females involves an ovary without an associated mass or cyst in as many as 46% of cases. The most common clinical symptom of torsion is sudden-onset abdominal pain that is intermittent, nonradiating, and associated with nausea and vomiting. If ovarian torsion is suspected, timely intervention with diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated to preserve ovarian function and future fertility.

In 50% of cases, adnexal torsion is not found at laparoscopy; however, in most instances, alternative gynecologic pathology is identified and treated. Adnexal torsion is a surgical diagnosis.

[Some] Recommendations And Conclusions [See the article for the complete list]

- The most common clinical symptom of torsion is sudden-onset abdominal pain that is intermittent, nonradiating, and associated with nausea and vomiting.

- There are no clinical or imaging criteria sufficient to confirm the preoperative diagnosis of adnexal torsion.

- Doppler flow alone should not guide clinical decision making.

- Although more than one half of cases of pediatric and adolescent adnexal torsion occur in the setting of an adnexal mass, cancer in this age group rarely presents as adnexal torsion.

- If ovarian torsion is suspected, timely intervention with diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated to preserve ovarian function and future fertility.

Background

Adnexal torsion, including torsion of a normal or pathologic ovary, torsion of the fallopian tube, paratubal cyst, or a combination of these conditions, is the fifth most common gynecologic emergency. Thirty percent of all cases of adnexal torsion occur in females younger than 20 years.

The risk of torsion increases when pelvic masses exceed 5 cm 7. The most common ovarian pathologies found in adolescents with adnexal torsion are benign functional ovarian cysts and benign teratomas 8. Torsion of malignant ovarian masses in this population is rare 9 6.

Sixty-four percent of torsions occur on the right side 10. The lower rate of torsion on the left side is attributed to the protective nature of the descending colon. In contrast to adnexal torsion in adults, adnexal torsion in pediatric and adolescent females involves an ovary without an associated mass or cyst in as many as 46% of cases 11. . . . If ovarian torsion is suspected, timely intervention with diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated to preserve ovarian function and future fertility.

Evaluation Of Adolescents With Adnexal Torsion

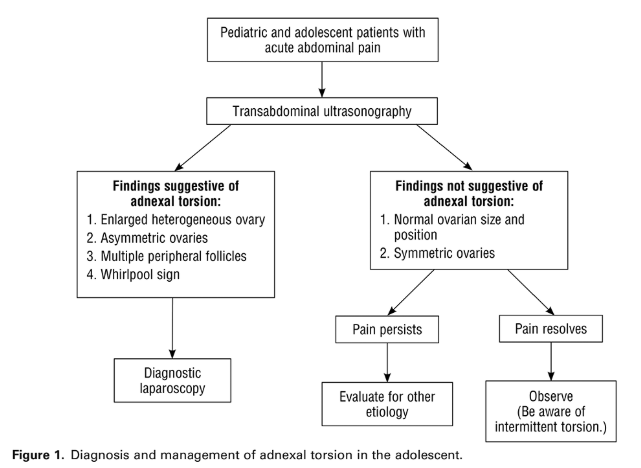

When evaluating adolescents with suspected adnexal torsion, an obstetrician–gynecologist or other health care provider should bear in mind that there are no clinical or imaging criteria sufficient to confirm the preoperative diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Patients with a clinical suspicion for adnexal torsion should undergo emergent diagnostic laparoscopy 13 Figure 1.

The differential diagnosis of an adolescent presenting with abdominal pain is broad 11 and the presentation of adnexal torsion is nonspecific. The most common clinical symptom of torsion is sudden-onset abdominal pain that is intermittent, nonradiating, and associated with nausea and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting are reported in 62% and 67% of cases, respectively 14. . . . Clinical signs of adnexal torsion include abdominal tenderness, which is reported in up to 88% of patients with adnexal torsion. Rebound and peritoneal signs are reported in only 12–27% of patients 14 16. Clinical signs also may include a palpable adnexal mass 17. However, a bimanual examination generally is not necessary or tolerated in pediatric and adolescent patients 6.

Transabdominal ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice. It has a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 96% in detecting adnexal torsion 18. When torsed, all ovaries are enlarged. A completely normal-appearing ovary on ultrasonography is unlikely to be twisted. In a study of 41 pediatric and adolescent patients with torsion, torsed ovaries on ultrasonography were on average 12 times the volume of the normal contralateral side 19.

Ultrasonography findings suggestive of ovarian torsion include unilateral ovarian enlargement, ovarian edema characterized by the presence of a hyperechogenic ovary with peripherally displaced follicles and echogenic stroma, free fluid, and a coiled vascular pedicle (referred to as the “whirlpool sign”) 17 Figure 2. The whirlpool sign is highly specific but technically difficult to visualize on transabdominal ultrasonography.

The use of Doppler studies in detecting adnexal torsion is limited because of their low sensitivity and operator dependency. The presence of Doppler arterial flow does not rule out torsion; for instance, one study reported normal Doppler arterial flow in as many as 60% of surgically confirmed cases of adnexal torsion 11. Preservation of Doppler arterial flow can be explained by intermittent torsion, collateral blood supply from the utero-ovarian vessels or infundibulopelvic vessels, or a torsed paratubal cyst. Doppler flow alone should not guide clinical decision making.

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging often is performed while evaluating a patient for causes of abdominal pain. If computed tomography imaging is obtained, findings that may indicate adnexal torsion include asymmetric ovarian enlargement, uterine deviation toward the pathologic side, pelvic free fluid, and fat stranding adjacent to the ovary 20. When computed tomography imaging suggests torsion, surgery should not be delayed to wait for ultrasonography 21. Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging may show decreased ovarian enhancement post contrast, asymmetric enlargement of the ovary, uterine deviation toward the pathologic side, and presence of multiple small peripherally located follicles, typically best seen on T2-weighted images 22

Adnexal torsion is a surgical diagnosis 7.