In this post, I link to and excerpt from Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8 to 60 Days Old [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. 2021 Aug;148(2):e2021052228. From the American Academy of Pediatrics.

All that follows is from the outstanding resource above.

Abstract

This guideline addresses the evaluation and management of well-appearing, term infants, 8 to 60 days of age, with fever ≥38.0°C. Exclusions are noted. After a commissioned evidence-based review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, an additional extensive and ongoing review of the literature, and supplemental data from published, peer-reviewed studies provided by active investigators, 21 key action statements were derived.

For diagnostic testing, the committee has attempted to develop numbers needed to test, and for antimicrobial administration, the committee provided numbers needed to treat.

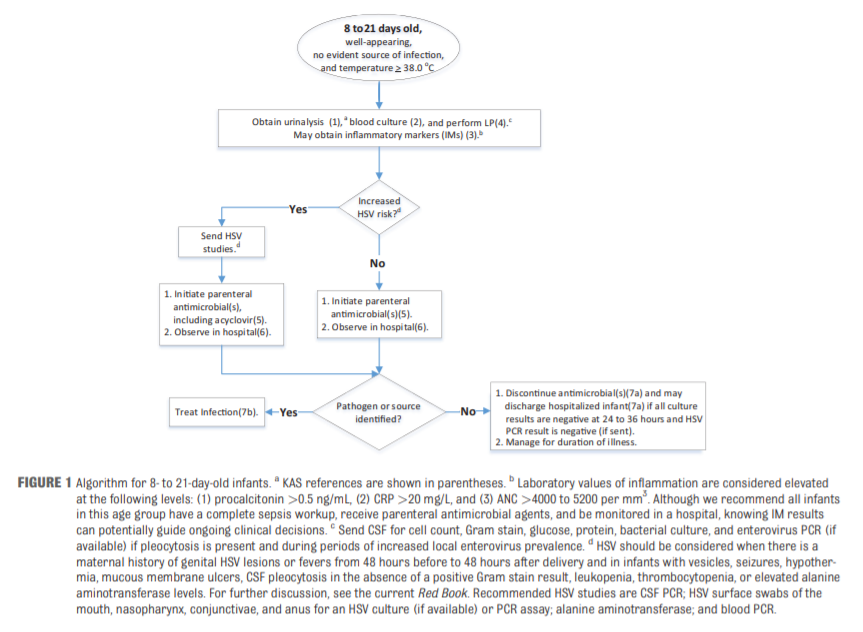

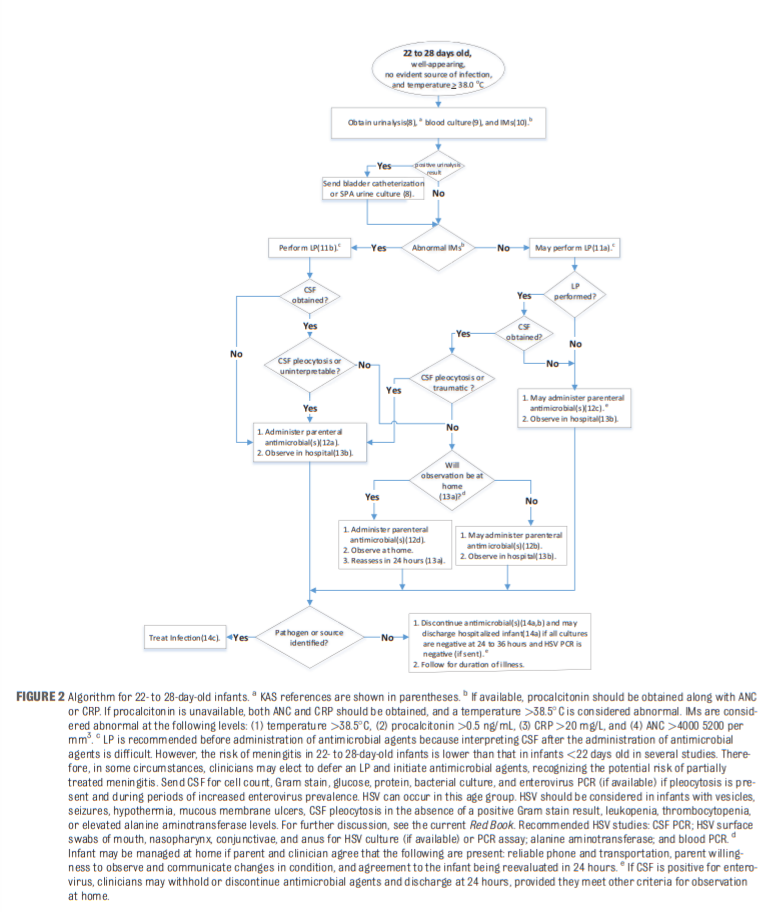

Three algorithms summarize the recommendations for infants 8 to 21 days of age, 22 to 28 days of age, and 29 to 60 days of age. The recommendations in this guideline do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

Three algorithms summarize the recommendations for infants 8 to 21 days of age, 22 to 28 days of age, and 29 to 60 days of age.

The recommendations in this guideline do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

BACKGROUND

Efforts to develop an evidence-based approach to the evaluation and management of young febrile infants have spanned more than 4 decades.1

In the 1970s, concerns arose about the emergence and rapid

progression of group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in neonates, whose clinical appearance and preliminary laboratory evaluations did not always reflect the presence of serious disease.2Such concerns led to extensive evaluations, hospitalizations, and antimicrobial treatment of all febrile infants younger than 60 days,3 with many institutions extending complete sepsis workups to 90 days.

However, the seminal 1983 study by De Angelis et al4

highlighted the iatrogenic complications that accompany

hospitalizing young, febrile infants and provided an impetus for

developing clinical strategies that would be more selective for

hospitalizations.Today, the consequences of medical errors during hospitalizations are [also] well known.5–7

In the 1980s and 1990s, there were numerous efforts to develop andvalidate clinical prediction modelsfor detecting serious bacterial illness (SBI).8–15

All [definitions] included urinary tract infection (UTI),

bacteremia, and bacterial meningitis, but UTI is so much more common than the other infections that it distorts models attempting to identify all causes.These prediction models involved a combination of clinical and

laboratory test parameters that were based on a priori criteria and were not derived from the primary data. Each variable was defined arbitrarily, such as age groupings in weeks or months and integers ending in zero, for which there is no real physiologic or biological basis.The models were promulgated because of moderately high sensitivities (90% to 95%) and high negative predictive values

(NPVs ) (97%–99%).The high NPVs were expected because of the uncommon occurrence of the most serious infections, which, along with

modest specificities, also explained the relatively low positive predictive values (20% to 40%).Despite these substantial efforts to develop prediction models, there has been ongoing evidence that community and emergency physicians do not routinely follow these recommendations in realworld settings.17,21–27

Clinical outcomes have not been shown to suffer despite nonadherence to contemporaneous standards of care.

Differing approaches to the management of very young febrile

infants indicated the need for a guideline that is current, evidence based, and developed by a national professional society or organization with broad representation.1. Changing Bacteriology

Sart here.