Please see and review Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8 to 60 Days Old [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. 2021 Aug;148(2):e2021052228.

The Cribsiders’ podcast #33 is based on the above resource.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Cribsiders’ #33: Febrile Infants – When Babies Are Too Hot. SEPTEMBER 1, 2021 By DR SAM MASUR.

All that follows is from the above outstanding resource.

Summary

Dr. Paul Aronson (Yale) joins the Cribsiders to help interpret the AAP’s new Febrile Infant Guidelines (July 2021) in this jam-packed episode. He teaches us about the new 22-28 day-old group, updated antibiotic recommendations, other major changes in the guidelines, and the evidence behind it all.

Febrile Infant Pearls

- The AAP released new guidelines for the febrile infant in July 2021. These guidelines apply to full-term infants, ages 8-60 days old, with temperature ≥ 38.0C in the past 24 hours, who are considered well appearing.

- The guidelines have divided these infants into 3 groups: ages 8-21 days-old, 22-28 days-olds, and 29-60 days-old.

- 8-21 day-old infants should receive the standard workup, including blood, urine, and CSF studies.

- 22-28 day-old infants should also be tested for abnormal inflammatory markers, which include height of fever, procalcitonin, absolute neutrophil count, and C-reactive protein. These tests can help determine the need for a lumbar puncture.

- 22-28 day-old infants can be sent home after a dose of ceftriaxone if CSF studies and inflammatory markers are normal.

- 29-60 day-old infants can avoid lumbar puncture entirely with normal inflammatory markers.

Febrile Infant Show Notes

Overview of Neonatal Fever [In The Well-Appearing Infant]

As of July 2021, the AAP has released new guidelines for the management of the well-appearing febrile infant, ages 8 to 60 days-old (Pediatrics 2021). These guidelines apply to full-term infants, ages 8-60 days old, with temperature(s) ≥ 38.0C in the past 24 hours, who are considered well-appearing.

The goal of the management of infants with fever is to catch and treat underlying bacterial infection. The term serious bacterial infection is no longer being used, rather it has been replaced with invasive bacterial infection (IBI) to refer to disease processes such as bacteremia and meningitis. The prevalence of IBI decreases as children get older. The distribution of bacterial infection in the febrile infant is broken down as below.

- Urinary tract infection is most common, accounting for > 10% of febrile infants

- Bacteremia accounts for approximately 2%

- Meningitis accounts for approximately 1%

Exclusion Criteria: for whom the guidelines do not apply

- Birth to 7 day-old infants. These infants are considered high risk, and full workup should be applied

- Infants less than 14 days old whose perinatal courses were complicated by maternal fever, infection, and/or antimicrobial use.

- Diagnosis of bronchiolitis

- Diagnosis of another focal bacterial infection such as cellulitis

- Premature infant

- Chronic medical condition or immunocompromised

- Infant who has received an immunization within the last 48 hours

- Infants with high suspicion of HSV infection such as vesicles on exam

- Ill-appearing

Dr. Aronson defines well-appearing as a personal assessment of how the infant is acting within his/her/their environment, which includes breathing pattern, color, tone, and ability to be consoled. This will always be a subjective assessment.

8 to 21 Day-Old Infants

Dr. Aronson recommends completing the following workup regardless of associated symptoms. Clinical exam alone does not exclude bacterial infection in this age group (Pediatrics 2017).

Workup

- Blood culture.

- Urinalysis. If positive, send urine culture. Positive UA defined as: +leuk esterase, +nitrites, or WBC > 5 cells/hpf. Diagnosis of bacterial UTI can only be made with BOTH a positive urine culture AND urinalysis.

- CSF cell count, protein, glucose, enterovirus (if appropriate), and culture; and HSV testing if there is an increased risk (entire episode on neonatal HSV!).

- Rapid viral panel does not change the recommended workup in this age. There is not enough literature yet to change the algorithm

- Inflammatory markers are not needed for diagnosis as they will not change management. They can be considered if they will guide your ongoing clinical decisions.

- Dr. Aronson recommends chest x-ray only in the presence of respiratory symptoms. The risk of pneumonia without respiratory symptoms is very uncommon.

- Dr. Aronson recommends stool studies only with profuse diarrhea or hematochezia. Nevertheless, the prevalence of gastroenteritis is quite low in this age group.

LP Pearls

- CSF pleocytosis is defined as >18 nucleated cells. Unless positive for enterovirus, Dr. Aronson recommends covering for HSV and bacterial meningitis with a CSF pleocytosis. Nevertheless, bacterial culture is considered the definitive test for bacterial meningitis. [Emphasis added]

- The guidelines recommend against correcting the WBC count for RBCs because the risk of a corrected false negative is not a tolerable risk.

- However, as an LP pearl for other situations, Dr. Aronson recommends using the traumatic tap correction factor of 1000 RBC:1 WBC above 10,000 RBCs (Pediatric Infectious Disease 2017).

- Dr. Aronson asks us to consider changing the “Champagne Tap” to the “Donation Tap”. He hopes that money used to buy champagne can go to a good cause instead.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to cover the most prevalent bacteria in this age group. E. Coli has become the most common pathogen for both UTI and bacteremia. Group B strep remains the most common organism for bacterial meningitis, followed by E. Coli. Recommendations for antibiotics and duration are as follows:

- If not concerned about meningitis, start: [ampicillin + gentamicin] OR [ampicillin + ceftazidime]

- If concerned about meningitis, start [ampicillin + ceftazidime] as gentamicin does not cross the blood brain barrier as well.

- These children should be admitted to the hospital on antibiotics awaiting culture growth. If cultures remain negative at 24-36 hours, the child may be discharged with close PCP follow up. This is because 90% and 95% of pathogens in the blood should grow within 24 hours and 36 hours, respectively.

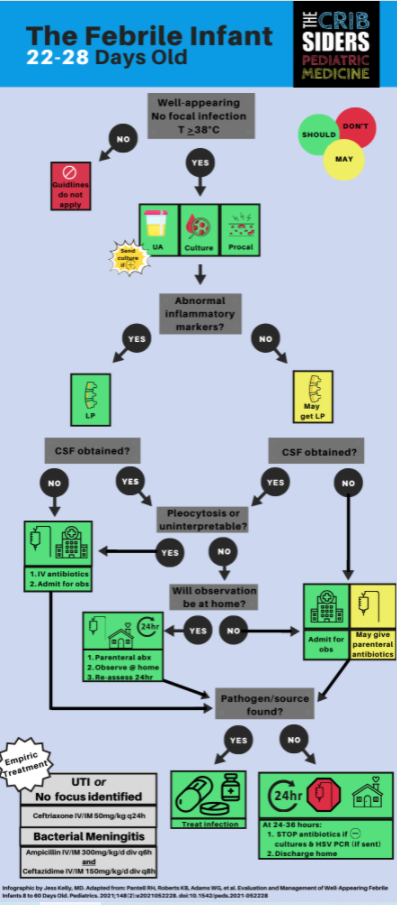

22 to 28 Day-Old Infants

Workup

- Blood culture

- Urinalysis (see recommendations above)

- Inflammatory markers, which is a new addition to the guidelines based on the PECARN (JAMA Pediatrics 2019) and Step-By-Step (Pediatrics 2016) algorithms. Inflammatory markers include: procalcitonin, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- If your institution has procalcitonin, Dr. Aronson recommends using either the PECARN or Step-By-Step approach to risk stratify, which also includes ANC or CRP.

- If your institution does not have procalcitonin, ANC and CRP should be used together. Abnormal inflammatory markers are defined as: fever ≥ 38.5C, ANC > 4000-5200, and CRP > 20mg/L. If all three are normal, the risk of IBI is considered to be low.

- Lumbar puncture is not necessarily required. Dr. Aronson recommends shared decision-making when choosing to perform a lumbar puncture. Although open to interpretation, lumbar puncture is recommended with abnormal inflammatory markers.

Treatment

The AAP guidelines include a new decision tree for 22-28 day old infants, which involves discharge home vs admission to the hospital. Shared decision-making should always be done when discussing the following options. Physicians should involve all parents equitably in this decision-making process, regardless of language, ethnicity, or financial resources.

- If no lumbar puncture is performed, the child should be admitted to the hospital. Antibiotics may be started or the child may be observed off antibiotics.

- As for the decision to start antibiotics vs observe, Dr. Aronson recommends observing off antibiotics (after talking with the admitting hospitalist and parents) as most well-appearing children with IBI do well, even with delayed antibiotic treatment.

- If the lumbar puncture is performed with normal inflammatory markers, and there is no pleocytosis, these children may be discharged home after a single dose of ceftriaxone with close PCP follow up.

- If not concerned about meningitis, the antibiotic of choice is ceftriaxone alone. The risk of bilirubin displacement and kernicterus due to ceftriaxone is considered extremely low at this age.

- If concerned about meningitis, the antibiotic of choice is [ampicillin + ceftazidime], similar to the 8-21 day-old infant.

- Once admitted, these children should remain in the hospital for 24-36 hours of negative culture data, similar to the 8-21 day-old infant.

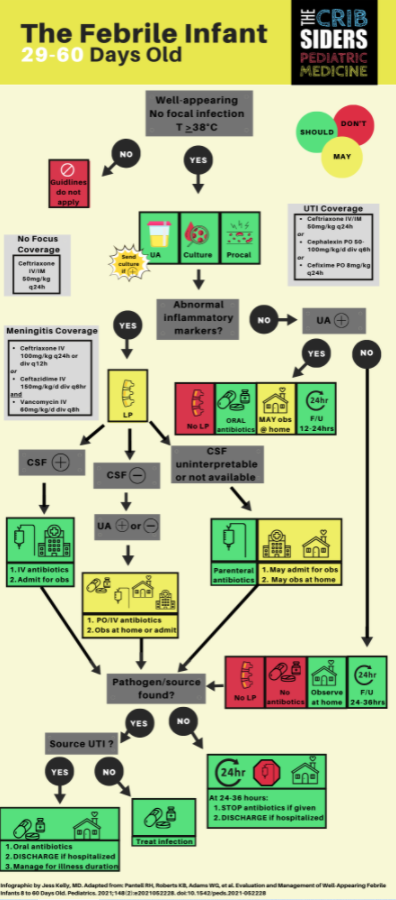

29 to 60 Day-Old Infants

Workup

- Blood culture

- Urinalysis. Bag method can be used; but if positive, the test should be repeated with a catheterization.

- Inflammatory markers (see above).

- If inflammatory markers are normal, lumbar puncture is unnecessary. This applies even if the infant has a UTI.

- If the inflammatory markers are abnormal, shared-decision making should occur, similar to the 22-28 day-old infant.

- Although there is not enough evidence to place the rapid viral panel in the guidelines, Dr. Aronson’s practice is to forgo the lumbar puncture in 29-60 day-old well-appearing infants with a positive viral test. This remains a very individualized choice.

Treatment

- If inflammatory markers are normal, these children may be discharged home with close PCP follow up.

- If the inflammatory markers are abnormal, shared decision-making regarding admission and antibiotics should occur, similar to the 22-28 day-old infant.

- If concerned about meningitis, the antibiotic of choice is [ceftriaxone/ceftazidime + vancomycin] to cover resistant gram-positives.

- If not concerned about meningitis, the antibiotic of choice is ceftriaxone alone, similar to the 22-28 day-old infant. The caveat is if there is a presumed UTI (positive UA and normal inflammatory markers), the infant should be started on oral antibiotics, such as cephalexin at home.

Take-Home Points

- The goal of these new guidelines is to balance the harms of overtreatment with the risks of missing invasive bacterial infection. There is no 100% correct way to do this, but these guidelines are a good summary of the current evidence.

- The febrile infant is now broken up into three age groups, including ages 8-21 day-olds, 22-28 day-olds, and 29-60 day-old infants.

- The 22-28 day-old infant is the new frontier, as we are now re-assessing how many invasive tests need to be performed.

- It is important to engage parents in decision-making, as we attempt to safely do less. These discussions need to be performed equitably with all parents, regardless of background.

Links

- The AAP REVISE-II QI collaborative to help standardize febrile infant care

- PECARN Research Group