In this post, I link to and excerpt from Dr. Josh Farkas‘ outstanding Internet Book Of Critical Care’s [Link is to the book’s table of contents] chapter, Autoimune Encephalitis, May 29, 2021 by Dr Josh Farkas.

I excerpt from materials I have reviewed on the internet because doing so helps me to remember the subject.

But readers should just review Dr. Farkas chapter directly as it is outstanding.

All that follows is from the chapter:

CONTENTS

- Definitions & classifications

- General clinical features

- Diagnostic evaluation

- Anatomic classification

- Classification by antibody

- Management of autoimmune encephalitis

- Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

definitions & classifications

autoimmune encephalitis

- Autoimmune encephalitis refers to a group of disorders which vary along numerous dimensions, as shown in the table below. This includes disorders associated with malignancy (paraneoplastic encephalitides), as well as postinfectious and idiopathic disorders.

- Diseases can also be subclassified based on their anatomic location, as well as the causative antibody. Both of these classifications will be explored further below, since both are useful in the process of diagnosing and treating these varied diseases.

- Our understanding of autoimmune encephalitis has advanced enormously in the past two decades. It is currently estimated that autoimmune encephalitis is as common as viral encephalitis (although historically, most cases of autoimmune encephalitis have eluded accurate diagnosis). With the increasing use of checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of malignancy, it’s conceivable that autoimmune encephalitis could become the most common form of encephalitis.

general clinical features

time course

- These disorders usually evolve over days to weeks.

- A nonspecific, viral-like prodromal illness is common (e.g., respiratory or gastrointestinal). Some cases may be preceded by a known viral illness (e.g., HSV encephalitis or COVID).

epidemiological risk factors

- Malignancy:

- Paraneoplastic encephalitides should be considered in patients with known malignancy or who are at-risk for malignancy (especially small cell lung carcinoma).

- Highest risk is associated with patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors.*

*Immune-related adverse events from checkpoint inhibitors

December 19, 2018 by Josh Farkas from The Internet Book of Critical Care.

- Autoimmune disorders:

- 25% of patients with autoimmune encephalitis may have an underlying autoimmune disorder.(PMC7122238)

- Family history of autoimmune disease may also increase risk.

symptoms

- Symptoms vary dramatically, depending on which neurological structures are involved.

- The most common symptoms include altered cognition, psychosis, or seizures. Various symptom patterns are discussed further below.

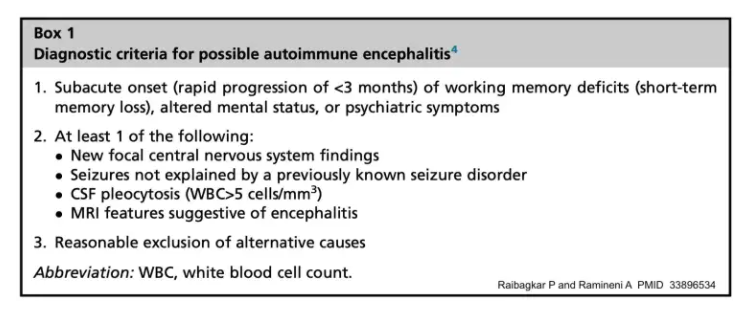

diagnostic criteria

- Describing a single set of diagnostic criteria for autoimmune encephalitis is largely impossible, since these disorders are so heterogeneous. Nonetheless, the criteria below may be useful to highlight some core aspects of these disorders.

CSF evaluation

CSF labs to consider

- Basic tests (e.g., cell count and differential, protein, glucose).

- Autoimmune tests:

- (1) CSF oligoclonal bands.

- (2) CSF albumin and IgG level (to allow for determination of the CSF IgG index).

- (3) Autoimmune encephalitis panel.

- Broad viral studies (including at least HSV 1/2 PCR & VZV PCR).

- Bacterial and fungal studies as appropriate.

- Cytology and flow cytometry.

accompanying serum labs

- Serum albumin and IgG level.

- Serum for oligoclonal bands.

- Serum autoimmune encephalitis panel. Some antibodies are easier to find in the CSF, whereas others are easier to find in the serum.

CSF findings

- CSF abnormalities seem to be relatively uniform across different types of autoimmune encephalitis.

- Pleocytosis with lymphocyte predominance. Generally, there are ~20-200 white blood cells/mm3, but there can be up to 900. Greater than five cells/mm3 is sufficient to meet the diagnostic criteria for pleocytosis.

- Protein is generally mildly elevated.

- Oligoclonal bands may be present (which can be absent in the serum).

- Elevated immunoglobulin G index (may be calculated using an online calculator).

limitations of laboratory testing

- Normal CSF studies don’t exclude autoimmune encephalitis. Thus, a CSF autoimmune encephalitis panel may be considered even if the routine CSF tests are normal.(33649022)

- Serum testing can yield false-positive antibody results (so if an isolated antibody is found in the serum and this doesn’t fit with the clinical picture, consider repeat testing).

- As more and more antibodies are discovered, there may be an increase in the rate of false-positive antibody test results.

- Some patients with autoimmune encephalitis may have negative serologic tests, because their antibody target hasn’t been discovered yet. Thus, lack of an identifiable antibody doesn’t exclude autoimmune encephalitis.

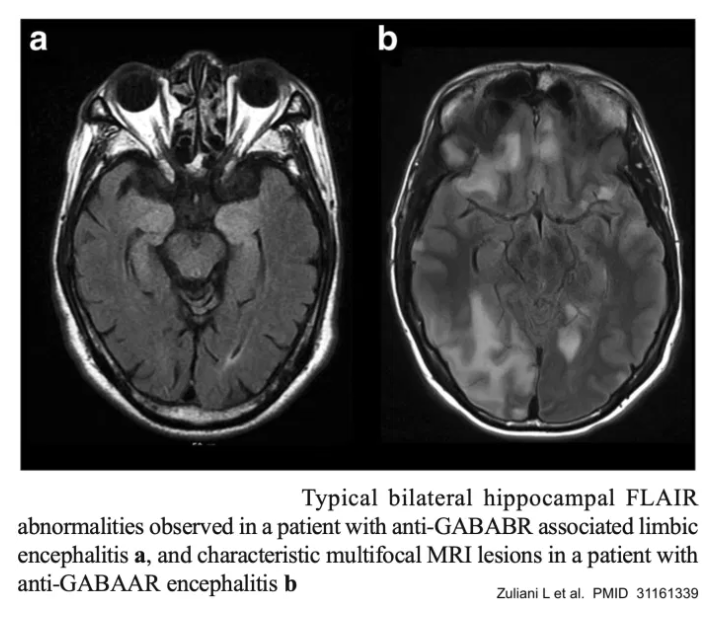

MRI

- MRI can reveal abnormalities that may point towards a specific anatomic syndrome (e.g., hyperintensities on FLAIR or T2 sequences).

- Overall, the sensitivity of MRI may be on the order of 70%, but this varies depending on the specific antibody involved.(31161339) MRI can be initially normal, with a repeat MRI subsequently showing abnormalities.(33649022)

- Mesial temporal lobe sclerosis may be a late finding, especially among autoimmune limbic encephalitides.(PMC7122238)

EEG

- EEG may show focal or multifocal abnormalities when MRI is negative. Abnormal EEG findings may support a diagnosis of encephalitis (rather than metabolic encephalopathy or schizophrenia), for example:(33649022)

- Focal slowing or seizures, especially localized to the temporal lobes.

- Periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs).

- Extreme delta brush, if seen, strongly suggests anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

evaluation for underlying malignancy

In patients where an autoimmune encephalitis is known or highly suspected, it may be reasonable to evaluate for an underlying malignancy. Depending on the context, the following studies may be considered:

- CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

- Transvaginal or testicular ultrasound.

- Whole body PET scan.

evaluation for underlying malignancy

In patients where an autoimmune encephalitis is known or highly suspected, it may be reasonable to evaluate for an underlying malignancy. Depending on the context, the following studies may be considered:

- CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

- Transvaginal or testicular ultrasound.

- Whole body PET scan.

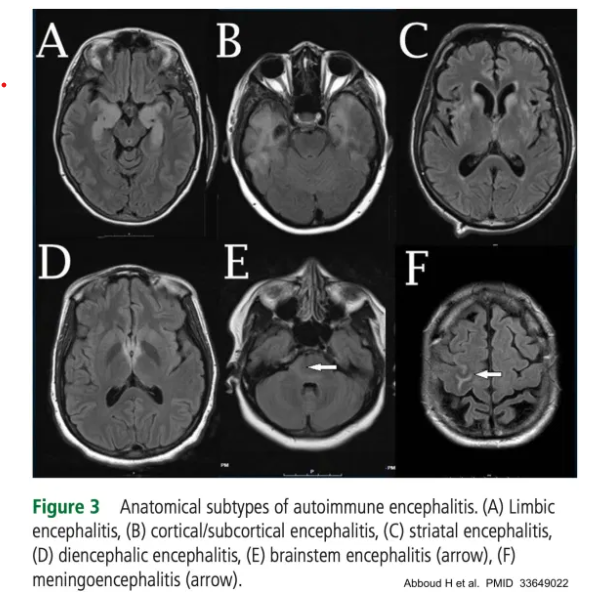

anatomic classification

Autoimmune encephalitides can be subclassified into groups based on which neuroanatomic structures are involved. This is an imperfect science, because many disorders can involve several anatomic regions simultaneously. Thus, for many patients, it will be impossible to neatly classify the encephalitis into a single category. Nonetheless, in some cases, anatomic subclassification can provide a useful approach to help narrow and focus the differential diagnosis. The classification below is based largely on a best practice recommendation by Abboud et al.(33649022)

limbic encephalitis

clinical syndromes

- Cognitive presentation (e.g., short-term memory loss).

- Psychiatric presentation (e.g., mood changes, psychosis).

- Epileptic presentation (e.g., complex partial seizures, status epilepticus which may be treatment-refractory).

- Hypothalamic dysfunction may cause hyperthermia, endocrine abnormalities, or somnolence.

differential diagnosis

- HSV, VZV.

- HHV-6 (human herpesvirus 6), among immunocompromised patients.

- Glioma (if unilateral or asymmetric abnormalities).

additional evaluations

- CSF viral PCR.

- CSF VZV IgG/IgM.

- CSF PCR microarray such as BioFire, if available.

diagnosis

- EEG may show epileptiform activity in the temporal regions.

- MRI may show T2 or FLAIR hyperintensity in the medial temporal lobes.

- This finding is ~80% sensitive (although sensitivity may vary between different antibodies).

- A characteristic MRI pattern with negative viral workup may be sufficient to render the diagnosis (even in the absence of an identified antibody; see diagnostic criteria below).

cortical-subcortical encephalitis

corresponding clinical syndromes

- Cognitive presentation.

- Seizure presentation.

differential diagnosis

- ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis).

- Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis.

- Tumefactive multiple sclerosis.

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

- Lupus cerebritis.

- Behcet’s disease.

- Neurosarcoidosis.

- Neurosyphilis.

- Lymphoma.

- Anoxic injury.

- Seizure-related changes.

possible additional tests

- Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein – IgG.

- JC virus PCR.

- CSF prior panel (14:3:3, with reflex tau and RT-QuIC).

- ANA.

- HLA-B51.

- Chest imaging to evaluate for sarcoidosis and possibly serum/CSF ACE levels.

- Treponemal antibodies.

- CSF cytology & flow cytology.

associated antibodies

- PCA-2 (MAP1b), NMDAR, GABA A/B R, DPPX, MOG

striatal encephalitis

presentation

- Movement disorder presentation.

differential diagnosis

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- West Nile virus.

- Toxic encephalopathy.

- Anoxic injury.

- Hyperglycemic injury.

- Uremia.

evaluation

- CSF prior panel (14:3:3, with reflex tau and RT-QuIC).

- West Nile virus IGM.

- CSF viral PCR.

- Metabolic panel.

- Toxicology screen.

associated antibodies

- CRMP5/CV2, DR2, NMDAR, LGl1, PD10A.

diencephalic encephalitis

start here