In this post I link to and excerpt from the Internet Book Of Critical Care‘s [Link is to the Table Of Contents] chapter, Bradycardia, by Dr. Josh Farkas, January 2017.*

*I excerpt from the chapter only because doing so helps me fix the chapter in my memory much like in olden days students would highlight their lecture notes or textbooks. Readers should just go to the chapter, Bradycardia, and review that because my excerpts are just that, excerpts, and don’t contain all the resources of Dr. Farkas’ chapter.

Dr. Farkas introduces the chapter by reminding us that:

Bradycardia emergencies are uncommon, but these cases can go sideways fast. An appropriately aggressive approach is needed to avoid cardiac arrest. Sometimes the answer is as simple as the appropriate epinephrine dose.

All that follows is from the above outstanding chapter.

CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference

- Why bradycardia is dangerous: physiology review

- Causes

- Evaluation

- Resuscitation overview

- Medical resuscitation arm

- Electrical resuscitation arm

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

rapid reference

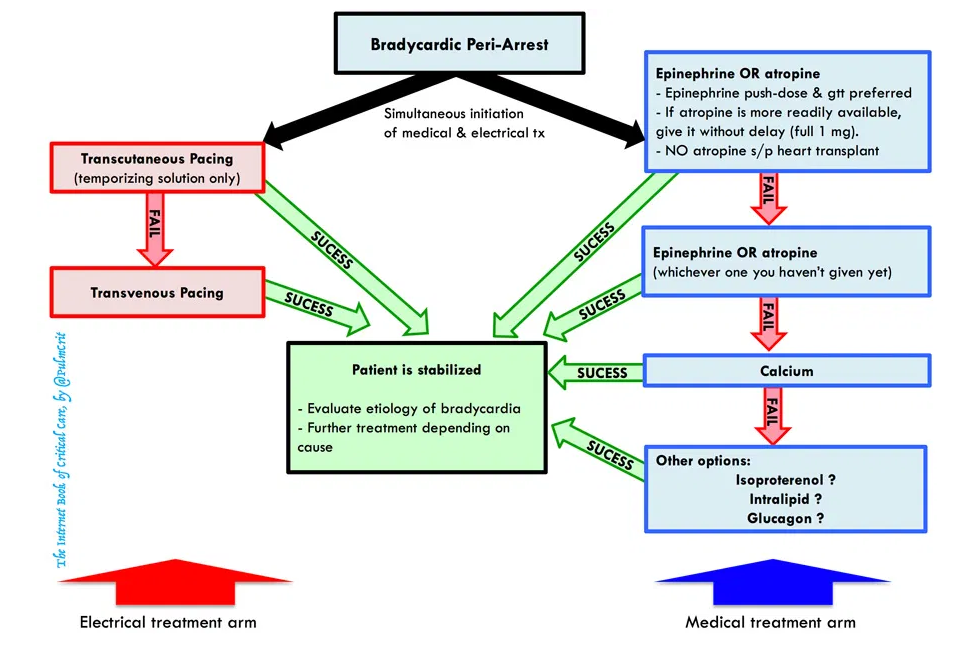

bradycardic peri-arrest:

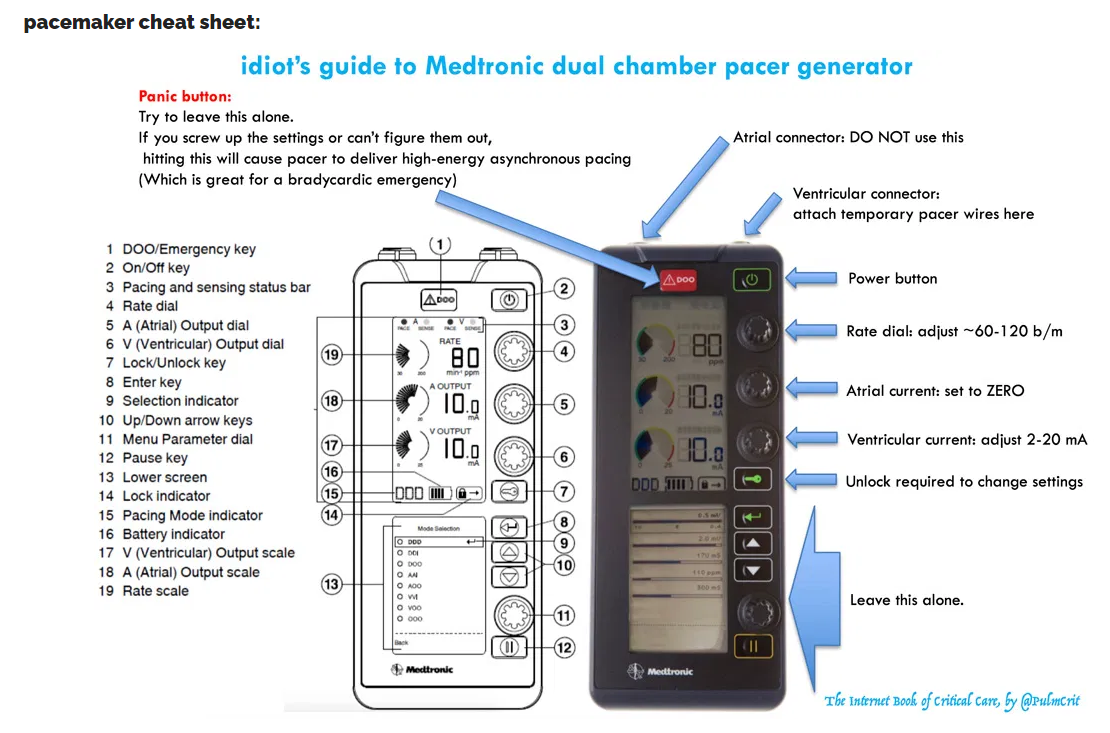

pacemaker cheat sheet:

why bradycardia is dangerous: physiology review

the effect of tachycardia on cardiac output is often over-estimated [See chapter for critical details]

the effect of bradycardia on cardiac output is often under-estimated [See chapter for critical details]

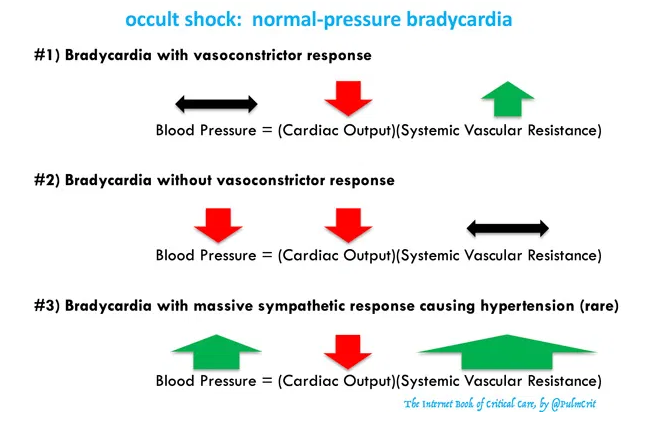

don’t be fooled by normal-pressure bradycardia [See chapter for critical details]

progressive bradycardia is often a harbinger of death

- Progressively worsening bradycardia is often seen immediately preceding death (“the patient is bradying down”).

- If the patient’s heart rate is consistently dropping in front of your eyes don’t just stand there – get some epinephrine. Fast.

- The differential diagnosis of bradycardia here is broader than usual and may include such entities as severe hypoxemia and right ventricular failure from massive PE. Immediate evaluation should focus on the ABCs: airway, breathing, and circulation (bedside echocardiogram).

one more reason to fear bradycardia: torsade de pointes

- Torsade de pointes is a pause-dependent arrhythmia, which is more likely to occur at slower heart rates. Furthermore, bradycardia itself may prolong the QT interval.1 2 It’s possible that leaving patients in a severely bradycardic state may increase their risk of torsade.

common causes

- Medication/intoxication:

- Beta-blocker or calcium-channel blocker.

- Central alpha-2 agonist (e.g., clonidine, dexmedetomidine, guanfacine).

- Cholinergic agent.

- Digoxin, antiarrhythmics.

- Propofol infusion syndrome.

- Alpha-blockers (e.g. prazosin).

- Intoxication with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or opioids can reduce the heart rate somewhat, but this isn’t usually a primary feature of the intoxication.

- Metabolic:

- Hyperkalemia, BRASH syndrome.

- Hypermagnesemia.

- Hypothyroidism (myxedema coma).

- Hypothermia.

- Hypoglycemia.

- Severe hypoxia / hypercapnia / acidemia (sinus bradycardia is a common pathway of impending death from any cause).

- MI

- Neurologic catastrophe:

- Cushing’s reflex due to increased ICP.

- Neurogenic shock.

- Infection:

- Lyme disease, syphilis.

- Aortic valve endocarditis with ring abscess (conduction block).

- Senile degeneration of sinus node or conduction system.

- Failure of a permanent pacemaker.

evaluation

physical exam

- Primary focus is adequacy of perfusion.

- Overt bradycardic shock: altered mental status.

- Occult bradycardic shock: Blood pressure and mental status intact, but cool extremities & poor urine output.

- Cardiopulmonary exam with ultrasound

- Volume status?

- Evidence of myocardial infarction (e.g. inferior wall motion abnormality)?

- Evidence of pulmonary congestion (e.g. B-lines throughout the lung fields)?

- Neuro/toxicologic exam

- Evidence of elevated intracranial pressure (e.g. stupor, widened optic nerve sheath)?

- Pinpoint pupils may suggest toxic ingestion (e.g. clonidine or cholinergic agent)

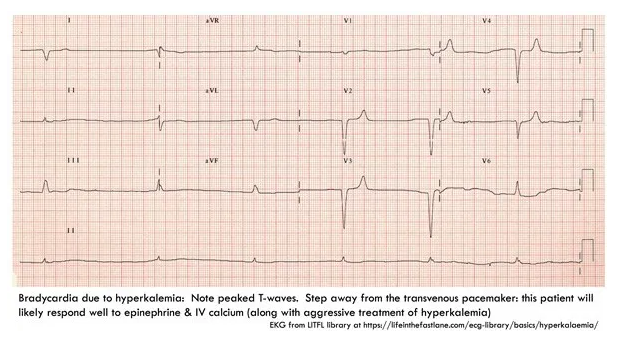

EKG: Focus on three things

- Rhythm diagnosis (e.g. sinus bradycardia vs. heart block)

- Signs of hyperkalemia (e.g. peaked T-waves)

- Signs of ischemia

medication review

- Active medication list?

- Recent medication changes, including dose titration?

- Some medications can unexpectedly cause bradycardia (e.g. donepezil, tizanadine).3 So if the patient just started a medication, look up whether it can cause bradycardia.

- Even eye drops with sympatholytic properties may be enough to cause bradycardia in elderly patients.4

- Interactions?

- Renally cleared meds plus acute kidney injury?

labs

- Fingerstick glucose if altered mental status

- Chemistries including Ca & Mg

- Troponin, if MI suggested by history/EKG

- Digoxin level, for patients taking digoxin

- Consider checking TSH, Lyme serology

resuscitation

atropine?

problems with atropine

- At low doses, atropine may cause paradoxical bradycardia.5 6 7 8

- Atropine works by poisoning the vagus nerve, so it is only effective for bradycardias mediated by excess vagal tone. It will predictably fail in cases of high-degree AV block.

- Contraindicated in patients who have had cardiac transplantation, in whom atropine may precipitate asystole.5

- Atropine may stabilize the patient for 30-60 minutes, but then wear off. This may initially make the patient appear stable, only to deteriorate later on (once everyone has stopped paying so much attention).

strategy when using atropine?

- If atropine is the most immediately available drug, then give it. Alternatively, if you have immediate access to epinephrine, it may be more effective to go straight to epinephrine.

- Atropine is traditionally the 1st-line medical therapy. However, for very unstable patients, epinephrine is more reliably effective and may be preferable.

- Start at 1 mg atropine, additional doses can be given to a maximal dose of ~3 mg.9

- Overall only ~25% of patients have a complete response to atropine, so don’t delay other therapies while waiting for atropine to work.10

- Don’t give atropine, sit back, and expect that it will fix everything. Give atropine while simultaneously preparing epinephrine and transcutaneous pacing, with the full expectation that the atropine will often fail.

epinephrine

epinephrine strategy

- Boluses for peri-arrest patient

- For patient on verge of a cardiac arrest, bolus with doses of ~20-50 mcg epinephrine.

- Boluses will stabilize the patient for a few minutes, but this is only a temporary bridge to an epinephrine infusion.

- Epinephrine infusion

- The usual dose is 2-10 mcg/min (but there is no hard upper limit in a crashing patient).

- Dosing strategy depends on how unstable the patient is. For more unstable patients, start high and down-titrate as the patient responds. For patients who are fairly stable, start low and gradually up-titrate.

- Figure out how to achieve this at your unit:

- a) If you have immediate access to pre-mixed epinephrine bags, know how to use them (know their concentration and how many ml’s are needed to deliver push-dose epinephrine).

- b) If you don’t have immediate access to pre-mixed epinephrine, then, read on…

creating & using a “dirty epi drip”

Mixing a bag of epinephrine is easy. This is conventionally termed a “dirty epi drip,” but if done properly it’s a safe and precise way to deliver epinephrine.

step #1: create the epinephrine reservoir bag

- Inject 1 mg of epinephrine into a liter bag of normal saline. One milligram of epinephrine can be obtained either from an entire syringe of cardiac epinephrine (1:10,000) or an entire vial of IM epinephrine (1:1000).

- Squish around the bag to mix well.

- Label the bag. The most elegant way to do this is using a pre-printed label which includes dosing instructions as shown below. But obviously this isn’t necessary.

step #2: push dose epinephrine

- For a patient in peri-arrest, you will want to deliver small boluses of epinephrine until the patient stabilizes.

- Fill up an empty 20 cc syringe with diluted (1 mcg/ml) epinephrine from your one-liter bag.

- Bolus the patient with 20 ml of this solution, which will deliver a bolus of 20 mcg epinephrine.

- Refill your 20 ml syringe and repeat as needed.

- Push-dose epinephrine is a temporizing solution. As soon as the patient stabilizes, start an epinephrine infusion.

step #3: epinephrine infusion

- Attach your bag of epinephrine to an infusion pump and set the rate. For example:

- Infuse at 60 ml/hour to achieve 1 mcg/min infusion

- Infuse at 240 ml/hour to achieve 4 mcg/min infusion

- Infuse at 600 ml/hour to achieve 10 mcg/min infusion

advantages of the “dirty epi” bolus & drip strategy:

- Relatively idiot-proof. As long as you mix well and label the bag, it should be pretty difficult to make dosing errors:

- Regardless of what type of epinephrine you use, you will be fine (either 1:1,000 or 1:10,000 will work).

- It’s physically impossible to bolus a lethal dose of epinephrine after it’s been diluted to 1 mcg/ml (you would need a >100 ml syringe, which doesn’t exist).

- Even if you run the epinephrine bag in wide open, you would only be delivering about ~30 mcg/min of epinephrine – so again, it’s basically impossible to deliver a lethally high epinephrine dose.

- Encourages a rapid transition from push-dose epinephrine to an epinephrine infusion (which is ultimately a safer and more controlled strategy).

- Viable approach during epinephrine shortages:

- Easily performed with 1:1000 epinephrine, if your shop runs out of 1:10,000 epinephrine.

- One vial of epinephrine can be used for both pushes & drip, conserving drug.

For more on vasopressors and shock, please see Vasopressors And Shock-Help From Drs. Weingart, Farkas, And Other Great Medical Educators.

Posted on June 25, 2021 by Tom Wade MD

The above post has an excellent infographic on the causes of vasopressor failure from EM Quick Hits 29 Vasopressor Failure, Asplenic Considerations, Bronchiolitis Update, ICD Electrical Storm, Night Shift Tips by Emergency Medicine Cases

And it is important to have an already prepared syringe of push-dose epinephrine for every Rapid Sequence Intubation and every case of procedural sedation for the rapid initial treatment of unexpected hypotension.

Please review the YouTube video, Push-Dose Pressors [Epinephrine and Phenylephrine], March 14, 2019 from CORE EM. This brief video shows you how to prepare syringes for the two medicines.

Returning now to the Internet Book Of Critical Care‘s [Link is to the Table Of Contents] chapter, Bradycardia, by Dr. Josh Farkas, January 2017.

calcium

Along with epinephrine, calcium is a drug which is often under-utilized in bradycardia. IV calcium is potentially effective for various etiologies listed below. Calcium is pretty safe (unless it extravasates), so when other therapies fail it makes sense to try to some calcium.*

*For more details on the administration of IV calcium gluconate, please see Calcium Gluconate. Anumita Chakraborty; Ahmet S. Can. Last Update: July 2, 2021. StatPearls [Internet].

calcium-responsive bradycardias:

- Hyperkalemia

- Hypocalcemia

- Hypermagnesemia

- Calcium-channel blocker

- Beta-blocker (maybe effective)

dosing

- Bradycardia of unknown etiology: Try one round of calcium (1 gram calcium chloride or 3 grams calcium gluconate).

- Known or suspected hyperkalemia: Start with 1 gram of calcium chloride or 3 grams of calcium gluconate. If ineffective and patient is dangerously unstable, consider additional calcium. The max dose of calcium is unknown in this situation. Bedside chemistry monitoring with an iSTAT might be helpful here, shooting for moderate hypercalcemia (e.g. ionized calcium level of 2-3 mM).

other medications [Please review this section of the chapter]

transcutaneous pacing [Please review this section of the chapter]*

*I have excerped the above section of the Bradycardia chapter in a separate post on my blog so that I can easily access the material. Please see Link To And Excerpt Of The Transcutaneous Pacing Section Of The Bradycardia Chapter From The IBCC

Posted on September 8, 2021 by Tom Wade MD

transvenous pacing [Please review this section of the chapter]*

*I have excerped the above section of the Bradycardia chapter in a seperate post on my blog so that I can easily access the material. Please see