Below are some resources on pediatric dehydration. And this post is my review of these resources (my review notes on the subject).

- Pediatric Dehydration Guideline From the Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne

- Assessing the Degree of Dehydration on Physical Examination, from Dr. Brad Sobolewski of pemcincinnati.com covers pediatric dehyation in a very short time.

- Oral Rehydration Therapy for Acute GastroEnteritis

BY SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 30, 2011 · UPDATED FEBRUARY 7, 2013 - Diarrhea and Dehydration BY SEAN FOX · MAY 10, 2013

- Oral Rehydration Therapy is Faster

BY SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED JANUARY 31, 2014 · UPDATED JULY 7, 2014 - Options to Intravenous Fluids

BY SEAN FOX · AUGUST 30, 2013

The first resource is Pediatric Dehydration Guideline From the Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne. Here are excerpts:

Background:

Dehydration can occur with many childhood illnesses. When assessing dehydration it is important to consider:

Degree of dehydration (deficit)

plus

Maintenance fluid requirements

plus

Ongoing lossesNote: If a child is haemodynamically unstable (ie shock) the shock needs to be corrected. [That is they need immediate parenteral fluid (IV or IO)]

Hypovolaemia

Give boluses of 10-20ml/kg of normal (0.9%) saline, which may be repeated. Do not include this fluid volume in any subsequent calculations of hydration.

Assessment

Degree of dehydration

Assess on clinical signs and documented recent loss of weight (NB: Bare weight on same scales is most accurate). Weigh bare child and compare with any recent (within 2 weeks) weight recordings. Precise calculation of water deficit due to dehydration using clinical signs is usually inaccurate. The best method relies on the difference between the current body weight and the immediate pre-morbid weight. Unfortunately this is often not available.

Clinical signs of dehydration give only an approximation of the deficit.

Patients with mild ( <4%) dehydration have no clinical signs. They may have increased thirst.

Moderate dehydration (4-6%) Severe dehydration (>/= 7%)

- Delayed CRT

(Central Capillary Refill Time) > 2 secs- Increased respiratory rate

- Mild decreased tissue turgor

- Very delayed CRT > 3 secs, mottled skin

- Other signs of shock (tachycardia, irritable or reduced conscious level, hypotension)

- Deep, acidotic breathing

- Decreased tissue turgor

Other ‘signs of dehydration’ (such as sunken eyes, lethargy & dry mucous membranes) may be considered in the assessment of dehydration, although their significance has not been validated in studies, and they are less reliable than the signs listed above.

Unless an accurate & recent loss of weight is available as a guide, calculating percentage weight loss by clinical signs is only an estimation.

Deficit

A child’s water deficit in mls can be calculated following an estimation of the degree of dehydration expressed as % of body weight. (e.g. a 10kg child who is 5% dehydrated has a water deficit of 500mls). The deficit is replaced over a time period that varies according to the child’s condition. Precise calculations (eg 4.5%) are not necessary. The rate of rehydration should be adjusted with ongoing assessment of the child

Replacement of deficit

Replacement may be rapid in most cases of gastroenteritis (best achieved by oral or nasogastric fluids), but should be slower in diabetic ketoacidosis and meningitis, and much slower in states of hypernatraemia (aim to rehydrate over 48 hours, the serum sodium should not fall by >1mmol/litre/hour).Ongoing losses (eg from drains, ileostomy, profuse diarrhoea)

These are best measured and replaced – calculations may be based on each previous hour, or each 4 hour period depending on the situation. (eg. 200ml loss over previous 4 hours becomes replacement of 50ml/hr for the next 4 hours.)Replacement of ongoing losses

Normal (0.9%) saline may be sufficient, or 5% albumin may be used if sufficient protein is being lost to lower the serum albumin. See Burns guideline for additional losses from burns.

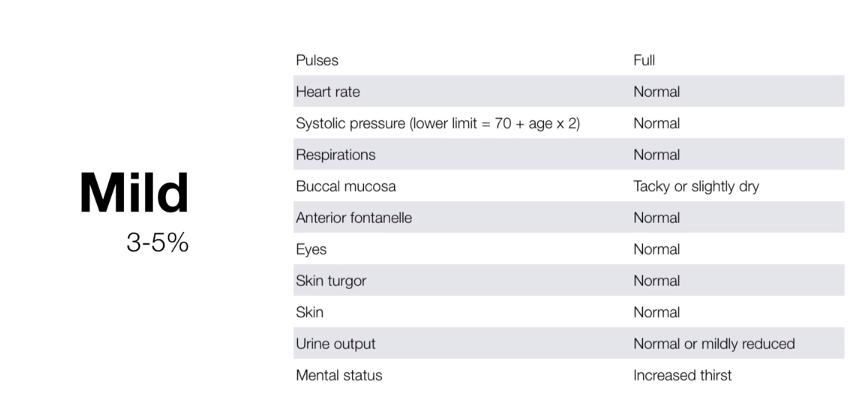

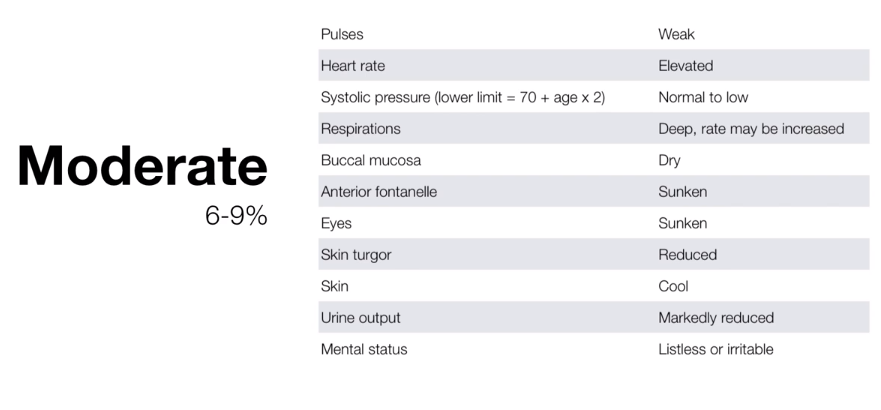

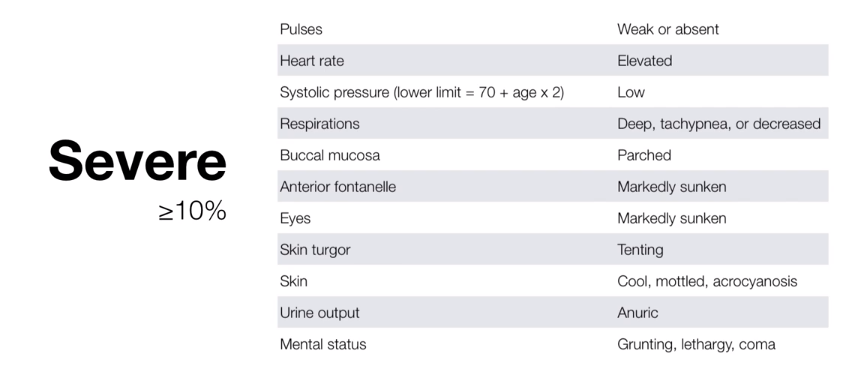

My second resource contains slides from the brief video (2:31) Assessing the Degree of Dehydration on Physical Examination, from Dr. Brad Sobolewski of pemcincinnati.com. This video is simply a very short review of the different degrees of dehydration. Here are the slides:

With mild dehydration, the vital sciences and mental status are all normal except that the buccal mucosa may be slightly dry.

In moderate dehydration the vital signs and mental status are abnorml. Be alert for compensated shock, and if suspected, begin vigorous parenteral fluid resuscitation.

In severe dehydration these patients are in critically ill and require immediate vigorous parenteral therapy.

Here are some excerpts from Oral Rehydration Therapy for Acute GastroEnteritis

BY DR SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 30, 2011:

- Oral Rehydration Solution, which was developed in the ~1970’s, have proven to be useful in preventing and treating dehydration from diarrhea of any eitiology in patients of all ages.

- Remember that Glucose enhances the absorption of sodium and water in the bowel.

- This works even with diarrhea present.

- Currently, Oral Rehydration Therapy is recommended as the first line therapy for mild to moderate dehydration regardless of where you live.\

- While worldwide ORT is known to be the 1st line, in the US, IV therapy is still often the default method for rehydration – why?

- [Oral Rehydration] CANNOT rapidly rehydrate someone – not useful in Sever Dehydration (AKA compensated SHOCK).

A few additional Morsels to consider when assessing the child with vomiting/diarrea:

- How dehydrated are they?

- Dehydration is not defined by any lab value (yes, labs may be affected, but an elevated BUN or specific gravity does not define dehydration or correlate with severity).

- Your physical exam defines the level of dehydration

- Carefully assess skin turgor, capillary refill, and respiratory pattern as these can be most useful in detecting severe dehydration early and are often underappreciated.

- For Mild/Moderate dehydration, educate about advantages of ORT and start them on the path (very useful if everyone is on the same page – so a protocol is fantastic (see attached)).

- For severe dehydration

- Check a glucose stat. Replete as needed. Start an IV and give 20ml/kg rapidly (over 5 minutes)… and then reassess.

- If you think the kid “looks punky” or “puny” or “kinda green” but they don’t fit the severe dehydration classification… think GLUCOSE, and check a fingerstick.

- Children will use up their glycogen stores rapidly and if they are not repleting them, they can easily become hypoglycemic. (I like to say, “They are like little alcoholics!”)

- Don’t wait for the BMP to return to show you that their sugar is 30 and for you to realize that the last 60 minutes of IVF hasn’t done them any good.

- There is no such thing as “PO Challenge” when it comes to AGE in children [Bold statement I know]

- You should not try to demonstrate that child is safe to go home by the fact that he/she doesn’t vomit while in the ED, because, the child will either throw-up on your discharge papers or in the parking lot or once they get home… and then the family will be back to see you and will be positive that the condition now warrants an IV.

- Instead, teach that the vomiting and diarrhea will continue and that via ORT (which you have been teaching them) performed at home will be sufficient to maintain the child’s hydration throughout the illness.

- Give them appropriate anticipatory guidance regarding the need to monitor for urine output (at least one urination in ~8hrs) and signs of true lethargy – for which they should return to the ED.

- Fluids can be given via NasoGastric Tube also!

The following are some excerpts from Diarrhea and Dehydration BY SEAN FOX · MAY 10, 2013:

Dr. Fox points out that the vomitting can be helped with Ondansetron but that it is actually the diarrhea that leads to dehydration:

however, in all honesty, it is the amount of diarrhea that will more likely lead to dehydration. What can be done for diarrhea and dehydration?

We have already reinforced the efficacy of Oral Rehydration Solutions in the treating dehydration. What, however, can you tell the family to help prevent dehydration in the first place?

It’s about volume!

- While, it is difficult to truly measure the amount of emesis or diarrhea, most recommend the following:

- For every episode of emesis, replete 2ml/kg.

- For every episode of diarrhea, replete 10ml/kg.

- Use an acceptable Oral Rehydration Solution to help maintain hydration.

- Fluids with too much sugar (ex, fruit juice) can lead to greater osmotic load in the intestinal lumen, producing more diarrhea.

However, the above formula for vomitting and diarrhea is pretty useless for American parents. You need to translate the information into a more useable form.

- [So], give [the parents] tangible goals based on [the above] information.

- For instance, let’s consider a 6 month old who weighs ~8kg

- After each episode of diarrhea, we would recommend 80mL of formula / breastmilk / oral rehydration solution.

- 30mL = 1 oz

- So, if the child consumes about 2.5 oz for every episode of diarrhea, the family can help prevent dehydration.

- Families understand this concept much better, as their lives often focus on fluid ounces, particularly early on in the child’s life.

- It can be useful to write out this goal on a prescription or other discharge instructions.