I’ve mentioned Capillary Refill and Shock from Dr. Fox’s Pediatric EM Morsels in the past on my blog. Today I’m going to review it again and complete the CME credit that is available from FOAMbase. I’ll also be reviewing Dr. Fox’s Pediatric Shock Index post. And I’ll be reviewing Episode 48 – Pediatric Fever Without A Source in a later post. And today’s post I’ll also review Episode 50 Recognition and Management of Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock from the incomparable Emergency Medicine Cases.

The big task in all pediatric patients is determining at the earliest moment whether the patient is seriously ill and potentially or actually unstable [what doctors mean when they say “the patient looks sick” versus not seriously ill]. And once that determination is made, we need to immediately begin appropriate therapy.

This determination is not at all easy. An infant or child can look deceptively normal until he or she becomes obviously critically ill (prearrest).

So with every pediatric patient we want to be alert for early signs of pediatric danger.

What follows are extracts from my review of Dr. Fox’s Pediatric Shock Index:

Fortunately, the critically ill child is not as common in the Emergency Department as the critically ill adult. Unfortunately, when the critically ill child does arrive, it can be challenging to recognize him/her initially. This can lead to delays in resuscitation care. . . . Often, though, by focusing on the Basics, we can met the challenge of detecting Pediatric Shock and act aggressively to treat it!

Pediatric Shock

- Broadly speaking, shock is the state in which there is a failure to meet the metabolic demands of the body leading to anaerobic metabolism. (Mtaweh, 2013)

- Often categorized as:

- Hypovolemic

- Cardiogenic

- Distributive

- Toxin mediated – Septic

- Hypersensitivity reaction – Anaphylaxis

- Loss of sympathetic tone – Neurogenic

Pediatric Shock: A Challenge

- The diagnosis is initially suspected based upon clinical exam.

- There is no lab value or “test” that defines shock. (See Lactate)

- Clinical Findings:

- Tachycardia

- Must account for age-adjusted values!

- Often children present with elevated heart rates without overt illness.

- Poor Capillary Refill

- Normal capillary refill can vary with age and is influenced by the environment. (Schriger, 1988)

- The initial cap refill in the ED, may artificially affected by the pre-hospital environment.

- Peripheral Pulse Quality

- Altered Mental Status

- Cold/Mottled Extremities

- Poor Urine Output

- Not likely useful in the initial assessment in the ED.

- If the patient is “hanging out” in your ED for some time, monitor this!

- Of these clinical findings, only Altered Mental Status and Poor Peripheral Pulse Quality was associated with development of Organ Dysfunction. (Scott, 2014)

- No single finding defines shock, but the absence of all of them is reassuring.

What follows are extracts from my review of Capillary Refill and Shock:

Shock: Pediatric Sepsis

- Significant cause of Non-traumatic childhood mortality in the USA. [Osterman, 2015]

- When recognized early and treated aggressively, morbidity and mortality can be decreased by 50%. [Han, 2003]

- Definition of pediatric SIRS differs from adult definition in that at least one diagnostic criteria must be fever or hypothermia. [Prusakowski, 2017]

- SIRS Criteria (2 of the following, with one being fever/hypothermia)

- Fever or Hypothermia (>38.5 degrees Celsius or <36 degrees Celsius.)

- Tachycardia

- No criterion to adjust for tachycardia in the presence of fever.

- Tachypnea

- Leukocytosis or Leukopenia (abnormal for age)

- Bandemia (>10% immature neutrophils)

- Sepsis, as with adults, requires the patient have SIRS criteria AND a known or suspected infection (bacterial or viral).

- Septic Shock is Sepsis with cardiovascular dysfunction (tachycardia/bradycardia AND impaired perfusion).

Shock: Recognition

- There is no single pathognomonic finding that defines shock.

- Hypotension is a late finding, but an ominous one, in kids.

- Constellation of findings:

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnea

- Poor perfusion

- Poor pulse quality

- Altered mental status

- Cold Shock findings:

- High Systemic Vascular Resistance

- Cold, clammy, mottled, or cyanotic extremities

- Capillary Refill > 2 seconds

- Diminished / thready pulses

- Narrow pulse pressure.

- Respect the “just ain’t right” findings:

- Poor feeding

- Jittery

- Irritable

- Lethargic

Be Aggressive Early

- Once recognized, be aggressive within 1st hour!

- IV or IO 40-60 ml/kg of isotonic fluids PUSHED rapidly

- Optimize oxygenation

- Supplemental may be all that is initially needed.

- 30-40% of a child’s cardiac output goes to the work of breathing when critically ill, so often will require additional support (i.e., intubation).

- [However, intubation and positive pressure ventilation can really drop the blood pressure. So be sure to fluid resuscitate patient first and have your push dose pressor (epinephrine) ready to go if you need it]

- Broad spectrum antibiotics

- Press the Pressors!

- Fluid-refractory shock is present if the patient, after 40-60 ml/kg, is hypotensive or has poor perfusion.

- Fluid-refractory shock should be treated with vasopressors via peripheral IV or IO.

- Ideally, they would be given via central line…

- The ED is, however, NOT an ideal environment…

- So start them peripherally and plan to change to central line once time permits.

Moral of the Morsel

- Shock is difficult to recognize and requires vigilance! Pay attention to capillary refill!

- Be aggressive early! Push the fluids in, don’t hang to gravity.

- Respect what the skin is telling you! Monitor the capillary refill time. If it is still prolonged after IV boluses, treat it like refractory shock.

The initial evaluation in all worrisome pediatric patients should include an immediate finger stick blood sugar. You don’t want to miss hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia (in the rare patient presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis).

The following is from Episode 50 Recognition and Management of Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock:

Adjunct Treatments in the Management of Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock

- Glucose: Remember to check the glucose in all children and treat as necessary. Both hypo and hyperglycemia are associated with worse outcomes. For glucose <6mmol, start D10W 5cc/kg (avoid higher concentration). (2)

- Corticosteroids: The use of hydrocortisone in pediatric septic shock is currently being investigated and its role is unclear. Consider using hydrocortisone 2mg/kg in any child that has fluid and inotropic resistant septic shock or proven adrenal insufficiency (1).

Goals of Resuscitation in Pediatric Septic Shock

Normalization of vital signs is a main goal. Aim for a normal blood pressure, pulse (without differences between central and peripheral pulses).

Clinically, the child should have a normal capillary refill, warm extremities and urine output >1ml/kg/hour indicating improved perfusion. Lactate and mental status should be normalized as well.

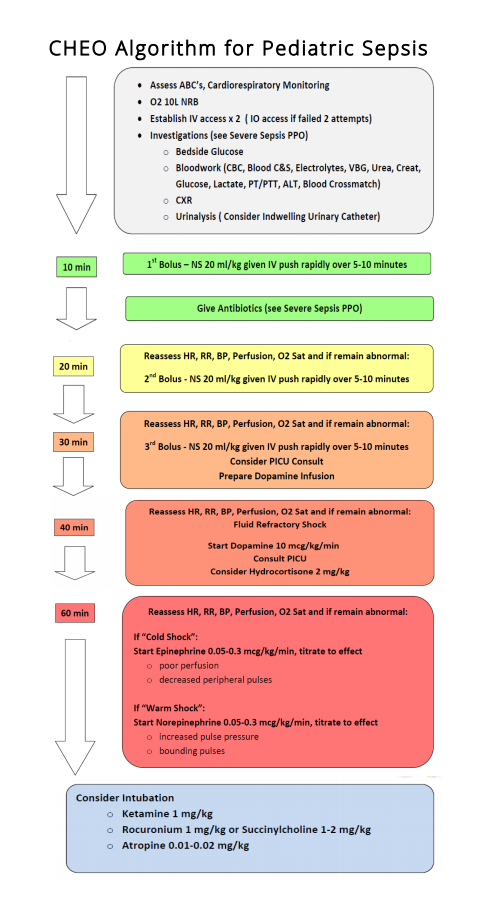

See below for The Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario pediatric sepsis algorithm.