I’ve divided these my study notes on the European high blood pressure guidelines into several parts for ease of my review. Links to all my post on the 2018 European Hypertension Guidelines are in Additional Resources after this post.

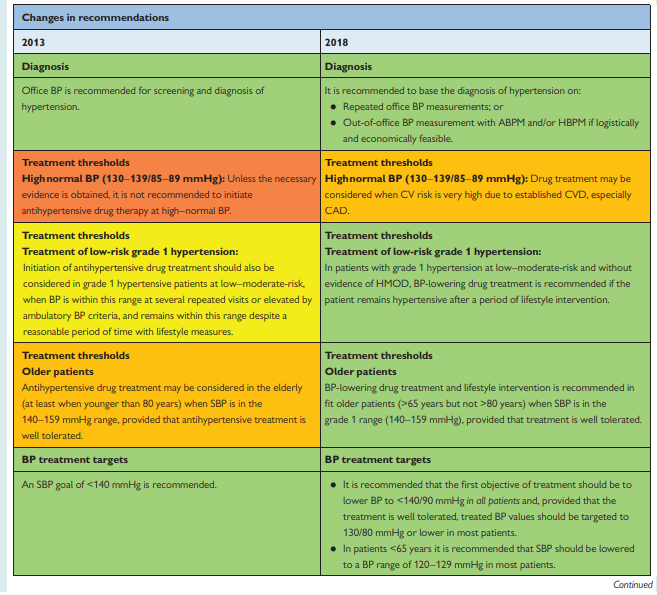

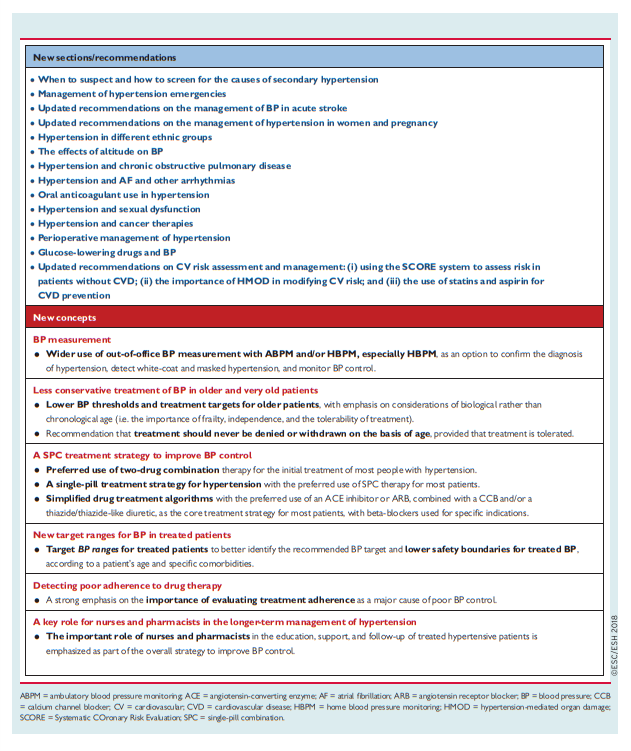

The following are Diagnosis Excerpts section from the 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39(33):3021-3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339:

3.4 Blood pressure relationship with risk of cardiovascular and renal events

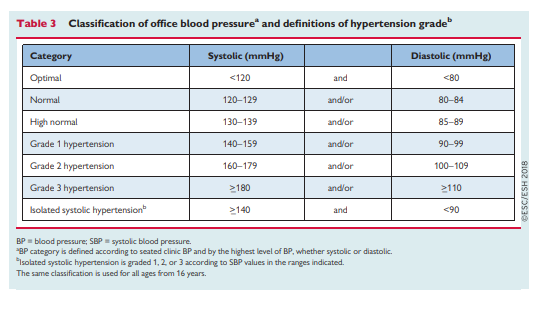

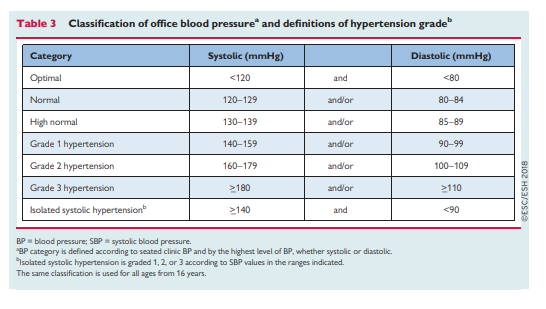

Elevated BP was the leading global contributor to premature death in 2015, accounting for almost 10 million deaths and over 200 million disability-adjusted life years.3 Importantly, despite advances in diagnosis and treatment over the past 30 years, the disability-adjusted life years attributable to hypertension have increased by 40% since 1990.3 SBP >_140 mmHg accounts for most of the mortality and disability burden (70%), and the largest number of SBP-related deaths per year are due to ischaemic heart disease (4.9 million), haemorrhagic stroke (2.0 million), and ischaemic stroke (1.5 million).3

Both office BP and out-of-office BP have an independent and continuous relationship with the incidence of several CV events [haemorrhagic stroke, ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, and peripheral artery disease (PAD)], as well as end-stage renal disease.4 Accumulating evidence is closely linking hypertension with an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation (AF),20 and evidence is emerging that links early elevations of BP to increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia.21,22

The continuous relationship between BP and risk of events has

been shown at all ages23 and in all ethnic groups,24,25 and extends from high BP levels to relatively low values.SBP appears to be a better predictor of events than DBP after the age of 50 years.23,26,27

High DBP is associated with increased CV risk and is more commonly elevated in younger (<50 years) vs. older patients. DBP tends to decline from midlife as a consequence of arterial stiffening; consequently, SBP assumes even greater importance as a risk factor from midlife.26 In middle-aged and older people, increased pulse pressure (the difference between SBP and DBP values) has additional adverse prognostic significance.28,29

Text

Text

Text

Text

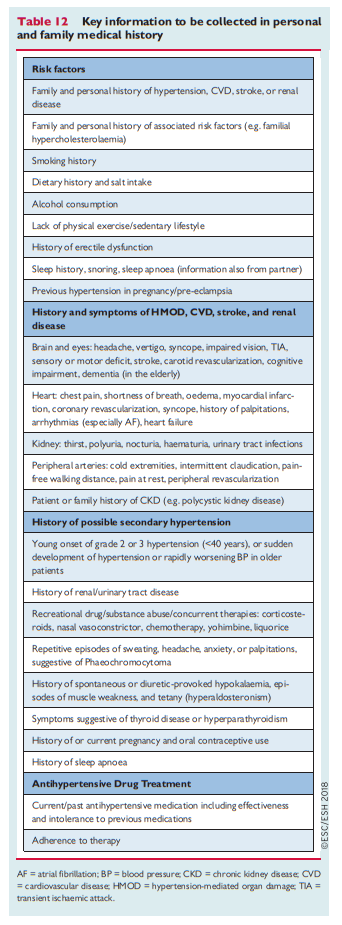

3.5 Hypertension and total cardiovascular risk assessment

Since 2003, the European Guidelines on CVD prevention have recommended use of the Systematic COronary Risk

Evaluation (SCORE) system because it is based on large, representative European cohort data sets (available at: https://www.escardio.org/

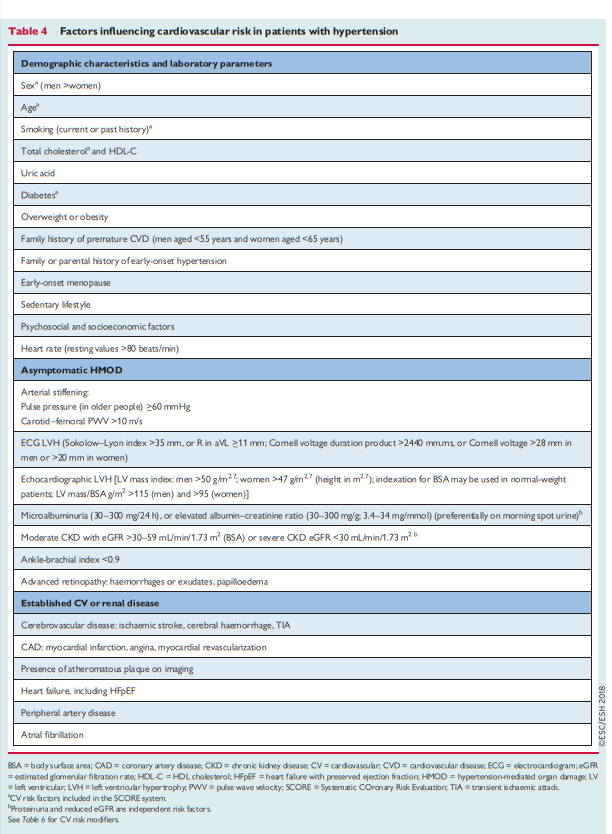

Guidelines-&-Education/Practice-tools/CVD-prevention-toolbox/SCORE-Risk-Charts). The SCORE system estimates the 10 year risk of a first fatal atherosclerotic event, in relation to age, sex, smoking habits, total cholesterol level, and SBP.Factors influencing CV risk factors in patients with hypertension

are shown in Table 4.

Hypertensive patients with documented CVD, including asymptomatic atheromatous disease on imaging, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, very high levels of individual risk factors (including grade 3 hypertension), or chronic kidney disease (CKD; stages 3 – 5), are automatically considered to be at very high (i.e. >_10% CVD mortality) or high (i.e. 5 – 10% CVD mortality) 10 year CV risk (Table 5 [below]). Such patients do not need formal CV risk estimation to determine their need for treatment of their hypertension and other CV risk factors.

For all other hypertensive patients, estimation of 10 year CV risk using the SCORE system is recommended. Estimation should be complemented by assessment of hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD), which can also increase CV risk to a higher level, even when asymptomatic (see Table 4 [Above] and sections 3.6 and 4)

The SCORE system only estimates the risk of fatal CV events.

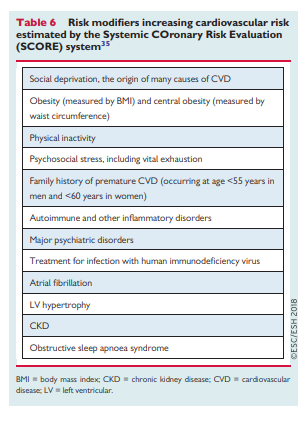

The risk of total CV events (fatal and non-fatal) is approximately three times higher than the rate of fatal CV events in men and four times higher in women. This multiplier is attenuated to less than three times in older people in whom a first event is more likely to be fatal.37There are important general modifiers of CV risk (Table 6) as well as specific CV risk modifiers for patients with hypertension. CV risk modifiers are particularly important at the CV risk boundaries, and especially for patients at moderate-risk in whom a risk modifier might convert moderate-risk to high risk and influence treatment decisions with regard to CV risk factor management.

3.6 Importance of hypertension mediated organ damage in refining cardiovascular risk assessment in hypertensive patients

A unique and important aspect of CV risk estimation in hypertensive patients is the need to consider the impact of HMOD.

Consequently, the inclusion of HMOD assessment is

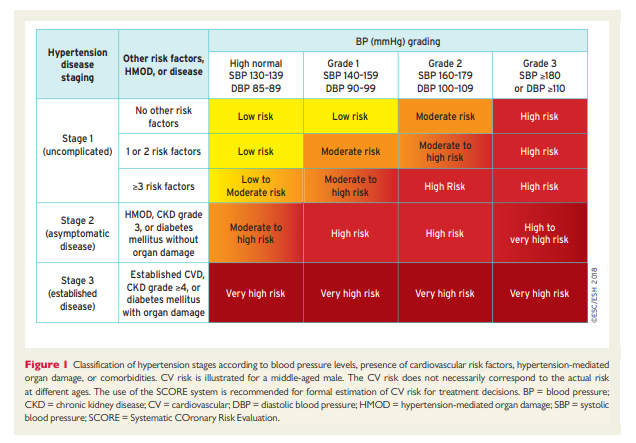

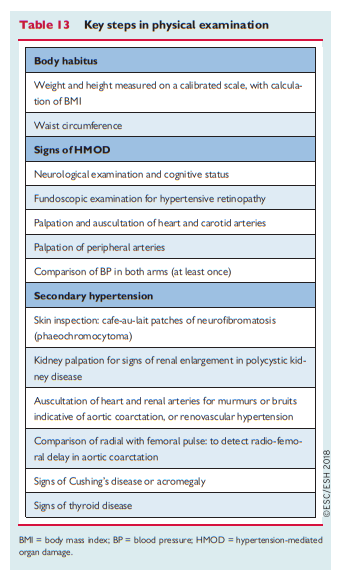

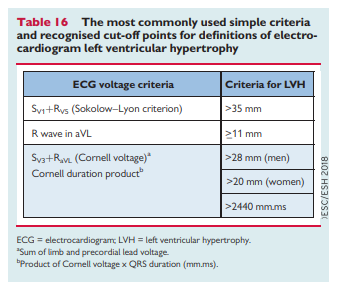

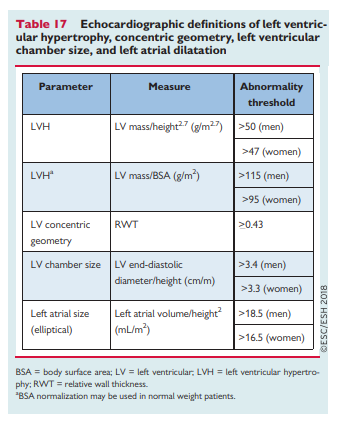

important in patients with hypertension and helps identify high-risk or very high-risk hypertensive patients who may otherwise be misclassified as having a lower level of risk by the SCORE system.42 This is especially true for the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), CKD with albuminuria or proteinuria, or arterial stiffening43 (see section 5). [See Table 4 above]The impact of progression of the stages of

hypertension-associated disease (from uncomplicated through to asymptomatic or established disease), according to different grades of hypertension and the presence of CV risk factors, HMOD, or comorbidities, is illustrated in Figure 1 for middle-aged individuals

4.1 Conventional office blood pressure measurement

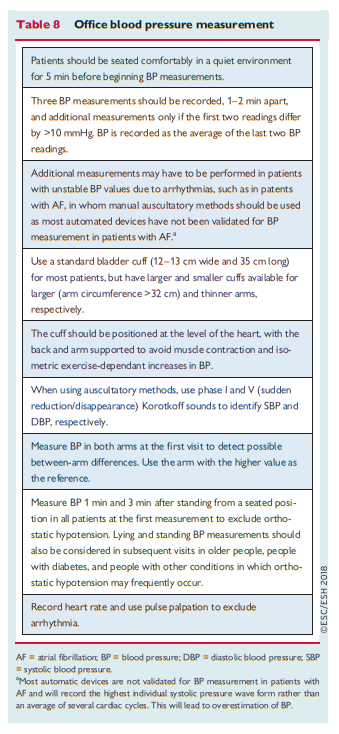

Auscultatory or oscillometric semiautomatic or automatic sphygmomanometers are the preferred method for measuring BP in the doctor’s office. These devices should be validated according to standardized conditions and protocols.44*

*See “HOW TO CHECK A HOME BLOOD PRESSURE MONITOR FOR ACCURACY” From The American Medical Association

Posted on November 14, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

Resuming excerpt from 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension:

4.4 Home blood pressure monitoring

Home BP is the average of all BP readings performed with a semiautomatic, validated BP monitor, for at least 3 days and preferably for 6–7 consecutive days before each clinic visit, with readings in the morning and the evening, taken in a quiet room after 5 min of rest, with the patient seated with their back and arm supported. Two measurements should be taken at each measurement session, performed 1–2 min apart.57

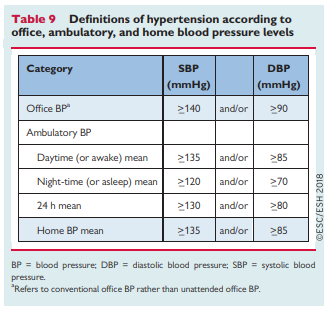

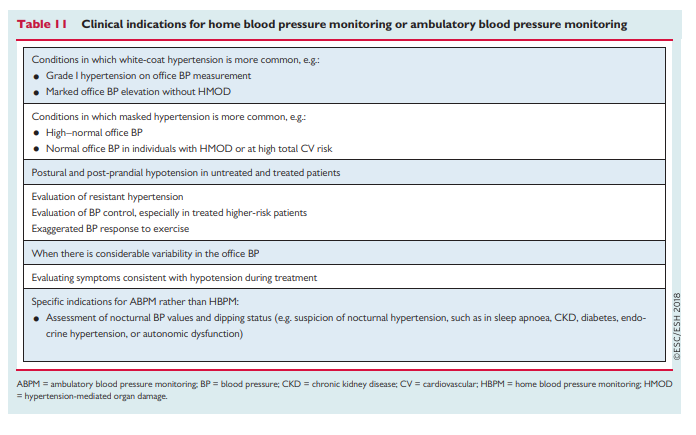

Compared with office BP, HBPM values are usually lower, and the diagnostic threshold for hypertension is >_135/85 mmHg (equivalent to office BP >_140/90 mmHg) (Table 9) when considering the average of 3–6 days of home BP values. Compared with office BP, HBPM provides more reproducible BP data and is more closely related to HMOD, particularly LVH.58

4.9 Confirming the diagnosis of hypertension

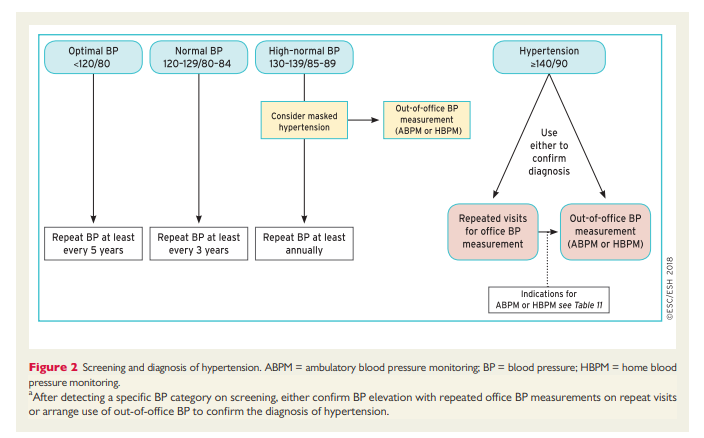

BP can be highly variable, thus the diagnosis of hypertension should not be based on a single set of BP readings at a single office visit, unless the BP is substantially increased (e.g. grade 3 hypertension) and there is clear evidence of HMOD (e.g. hypertensive retinopathy with exudates and haemorrhages, or LVH, or vascular or renal damage). For all others (i.e. almost all patients), repeat BP measurements at repeat office visits have been a long-standing strategy to confirm a persistent elevation in BP, as well as for the classification of the hypertension status in clinical practice and RCTs. The number of visits and the time interval between visits varies according to the severity of the

hypertension, and is inversely related to the severity of hypertension. Thus, more substantial BP elevation (e.g. grade 2 or more) requires fewer visits and shorter time intervals between visits (i.e. a few days or weeks), depending on the severity of BP elevation and whether there is evidence of CVD or HMOD. Conversely, in patients with BP elevation in the grade 1 range, the period of repeat measurements may extend over a few months, especially when the patient is at low risk and there is no HMOD. During this period of BP assessment, CV risk assessment and routine screening tests are usually performed

(see section 3).These Guidelines also support the use of out-of-office BP measurements (i.e. HBPM and/or ABPM) as an alternative strategy to repeated office BP measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension, when these measurements are logistically and economically feasible (Figure 2).99

And now go on to

- Part 2 Hypertension Therapy-Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension

Posted on November 10, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

Resources:

(1) Diagnosis Of Hypertension-Part 1 Of Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension

Posted on November 10, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

(2) Treatment Of Hypertension- Part 2 Of Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension

Posted on November 10, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

(3) The Drug Treatment Algorithm For Hypertension – Part 3 Of Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension Posted on November 16, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

(4) Resistant Hypertension – Part 4 Of Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension

Posted on November 16, 2019 by Tom Wade

(5) Secondary Hypertension – Part 5 Of Links To And Excerpts From The 2018 European Guidelines For The Management Of Hypertension

Posted on November 18, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

(1) 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39(33):3021-3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.

(2) 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. [PubMed Citation] [Full Text PDF]. Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. Epub 2017 Nov 13.

(3) Screening for Endocrine Hypertension: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Endocrine Reviews, Volume 38, Issue 2, 1 April 2017, Pages 103–122

(4) 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Atherosclerosis. 2016 Sep;252:207-274. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.037.

(5) “HOW TO CHECK A HOME BLOOD PRESSURE MONITOR FOR ACCURACY” From The American Medical Association

Posted on November 14, 2019 by Tom Wade MD