Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ Ep 208 Paradigm Shift in Ischemic Stroke Management Part 1: Disabling Strokes.*

*Helman, A. Himmel, W. Lin, K. A Paradigm Shift in Ischemic Stroke Management Part 1: Disabling Strokes. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2025. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/ischemic-stroke-management-disabling-strokes. Accessed November 10, 2025

All that follows is from the above outstanding resource.

Ep 208 Paradigm Shift in Ischemic Stroke Management Part 1: Disabling Strokes

We are amidst a paradigm shift in the emergency management of acute ischemic stroke. The traditional way of categorizing ischemic strokes as ‘minor’ vs ‘major’ is no longer relevant to what we do in the ED. It’s now about ‘disabling’ vs ‘non-disabling’ strokes. And this is no small change. This categorization dictates urgency of ED work-up and treatments, imaging choices, treatment decisions and goals of care. In this Part 1 or our 2-part main episodes EM Cases podcast series on management of ischemic stroke with Dr. Walter Himmel and Dr. Katie Lin, we answer questions like: How can we best rapidly determine if an ischemic stroke is disabling or non-disabling at the bedside? In what ways are ‘wake up strokes’ managed uniquely and what’s the latest thinking on their pathophysiology? How should we best prioritize imaging depending on timing, geography and resources? How do we best predict large vessel occlusion amenable to endovascular therapy (EVT) at the bedside? How can we efficiently establish goals of care at the bedside to inform our emergency decision making around strokes? Which is better for thrombolysis in ischemic stroke – Tenecteplase or Alteplase? How have contraindications to IV thrombolysis changed over the last decade? When should we consider bridge therapy with EVT after IV thrombolysis? What are 4 key items the ED physician should have ready for the stroke neurologist on the first call? and many more…

Podcast: Play in new window

Download (Duration: 1:36:12 — 88.1MB)

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman; Voice editing by Braedon Paul

Written Summary and blog post by Anton Helman October, 2025

Major vs Minor Stroke – An impractical categorization of stroke

The historical “major (NIHSS ≥5) vs minor (NIHSS <5)” dichotomy is convenient for research stratification but problematic clinically: so-called “minor” presentations (e.g., isolated aphasia, dense hemianopia, disabling distal limb weakness of the dominant hand) frequently carry marked functional morbidity and should not be excluded from reperfusion solely on the basis of a low NIHSS. The contemporary approach reframes categorization around disability and patient-centred outcomes rather than an arbitrary score threshold.

NIHSS is a descriptor, not a decision tool. A low score can still be functionally catastrophic and should not exclude reperfusion.

Pitfall: One pitfall in the decision to employ IV thrombolytics and/or endovascular therapy (EVT) is to assume that a minor stroke (NIHSS <5) is not eligible for such therapies. Many patients who have an NIHSS <5 have disabling stroke that do fulfill criteria for these aggressive, time dependent therapies.

Major vs Minor Stroke – An impractical categorization of stroke

The historical “major (NIHSS ≥5) vs minor (NIHSS <5)” dichotomy is convenient for research stratification but problematic clinically: so-called “minor” presentations (e.g., isolated aphasia, dense hemianopia, disabling distal limb weakness of the dominant hand) frequently carry marked functional morbidity and should not be excluded from reperfusion solely on the basis of a low NIHSS. The contemporary approach reframes categorization around disability and patient-centred outcomes rather than an arbitrary score threshold.

NIHSS is a descriptor, not a decision tool. A low score can still be functionally catastrophic and should not exclude reperfusion.

Pitfall: One pitfall in the decision to employ IV thrombolytics and/or endovascular therapy (EVT) is to assume that a minor stroke (NIHSS <5) is not eligible for such therapies. Many patients who have an NIHSS <5 have disabling stroke that do fulfill criteria for these aggressive, time dependent therapies.

Disabling vs Non-disabling – The practical categorization of ischemic stroke

Reframe the first decision point as disabling vs non-disabling. A structured conversation around values helps determine whether a deficit is “disabling” for this patient. At the bedside, determine whether the deficit is disabling for this patient—i.e., likely to compromise independent living, employment, or meaningful communication. Cortical signs (aphasia/dysphasia, neglect, gaze deviation, hemianopia) combined with significant motor deficits imply a high pretest probability of large-vessel occlusion (LVO) and generally warrant aggressive reperfusion pathways when imaging and contraindication screening align with benefit. [Emphasis added] A patient-centred frame improves both selection for reperfusion and shared decision-making. Classify the presentation as disabling when it threatens independence or meaningful quality of life (speech/language, vision, ambulation, dominant-hand function, or level of consciousness), and nondisabling when deficits are unlikely to impact these domains if untreated. This “disability” lens operationalizes risk-benefit conversations around things patients value (home, work, communication), rather than a numerical threshold.

Core principle: Focuses on deficits that disrupt independence and meaningful activities, e.g., speech, vision, motor, consciousness.

Features typically considered disabling:

Speech: Major speech deficit (severe aphasia or dysarthria compromising functional communication)

Motor: Dense motor loss (especially dominant hand/arm, profound leg weakness)

Vison: Amaurosis fugax, cortical blindness, dense hemianopia.

Consciousness/Brainstem: depressed level of consciousness, locked-in syndrome from basilar occlusion.

Patient and family context:

What is disabling varies with occupation, age, lifestyle.

Shared decision-making is vital for subtle deficits.

Implementation: ED teams must weigh patient’s premorbid status, functional demands, and goals of care.

Bedside script (shared decision-making): “There are time-sensitive treatments that can help, but they carry bleeding risks (~3–5% symptomatic ICH with IV thrombolysis).* Given your deficits and what matters to you, are these risks acceptable to try to preserve speech/hand/ambulation?”

*For more information on the consequences of post IV thrombolysis intracranial hemorrhage, please see my Google search:What are the clinical results of intracranial hemorrage from IV thrombolysis?

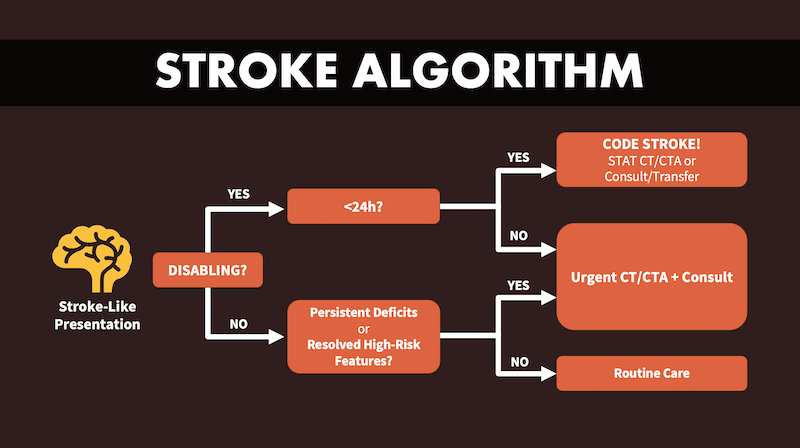

Below is Dr. Lin’s basic ischemic stroke algorithm based on the ‘disabling’ vs ‘non-disabling’ categorizations of stroke to be used as a framework for these 2 EM Cases episodes on ED management of ischemic stroke.

The Importance of Time Windows in Disabling Ischemic Stroke Management

- 0–4.5 h: May be eligible for IV thrombolysis (per local protocol); a subset also proceeds to EVT when CTA confirms large vessel occlusion (LVO) – see ‘bridge therapy’ below.

- 4.5–6 h: IV thrombolysis generally excluded; EVT remains indicated when CTA demonstrates large vessel occlusion (LVO)—no additional imaging beyond CTA is required for selection in this interval.

- 6–24 h (late window): Selection hinges on advanced imaging beyond CTA to demonstrate a small infarct core with a robust penumbra (e.g., favorable CTP, multiphase CTA collaterals, or MRI mismatch).

The Significance of ‘Last Seen Normal’ in Ischemic Stroke Management

- Definition: Last time patient was at neurologic baseline (not just symptom onset).

- Utility: Determines upper time boundary for treatment eligibility.

- Application: Especially critical in unwitnessed and “wake-up” strokes.

- Acute therapies: IV thrombolysis usually offered up to 4.5 hours, EVT up to 24 hours, all measured from “last seen normal.”

- Evidence: Late window trials (DAWN, DEFUSE3) justify aggressive intervention ≤24 hours with favorable imaging.

“Last seen normal” (LSN) anchors onset time when symptoms are unwitnessed; however, LSN should not be conflated with tissue viability. Patients presenting close to 24 h from LSN may still be candidates for late-window endovascular therapy (EVT) if imaging reveals a small infarct core with a substantial penumbra. Practically, LSN documents chronology; selection for therapy is driven by imaging-demonstrated salvageable tissue.

“Wake Up” Strokes – Where urgent imaging is paramount

A wake up stroke occurs when precise onset is unknown, but “last seen normal” is when patient went to sleep. Most wake-up strokes occur just before awakening due to physiologic changes (cortisol/BP spikes), a time at which there is likely to be more salvagable tissue that can be saved by EVT than if the time of the stroke occurred upon falling asleep. Imaging may be more likely to reveal salvageable tissue, making many wake-up stroke patients candidates for EVT. Many patients treated in the extended (≤24 h) reperfusion window in landmark thrombectomy trials (Dawn, Extended IA, Diffuse 3) were wake-up strokes; physiology (diurnal BP/cortisol surge) suggests many such events occur shortly before waking. Unknown onset should trigger, not throttle, reperfusion work-up. Do not exclude patients from EVT on time grounds for wake up strokes; instead, expedite imaging for all suspected wake-up strokes.

Pitfall: Do not exclude wake up stroke patients from EVT on time grounds alone; instead, expedite imaging for all suspected wake-up strokes, as many of these strokes occur close to the time of awakening.

Treat wake up strokes as time-critical like any stroke: Non-contrast CT to exclude hemorrhage + CTA head/neck to assess for LVO; add advanced imaging (CTP, multiphase CTA, or MRI DWI–FLAIR mismatch) when beyond standard IV thrombolysis windows or onset is uncertain. Consider IV thrombolytics (TNK or tPA per local protocol) when advanced imaging shows salvageable tissue (e.g., DWI–FLAIR mismatch or favorable CTP profile) and there are no contraindications. If CTA shows LVO, proceed down your EVT pathway. In unknown/late windows, use CTP/multiphase CTA/MRI to confirm a small core with salvageable penumbra. Bridging lysis is still reasonable when eligible (anatomy may preclude rapid catheter access, and early recanalization can occur while mobilizing the suite).