Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. [No Abstract Available] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Eur Heart J. 2024 Sep 29;45(36):3415-3537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177.

There are 101 similar articles in PubMed.

The above article has been cited 572 times in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Keywords: Guidelines, Antianginal therapy, Antithrombotic therapy, Atherosclerosis, Clinical likelihood, Chronic coronary syndromes, Coronary artery disease, Diagnostic testing/algorithm, Heart team, Lipid-lowering therapy, Microvascular disease, Myocardial ischaemia, Myocardial revascularization, Outcomes, PROMS/PREMS, Shared decision-making, Stable angina, Vasospasm

Topic: angina pectorisfibrinolytic agentsischemiamyocardial ischemiacoronary artery bypass surgerycoronary arteriosclerosiscoronary arterycoronary revascularizationfollow-updiagnosisdiagnostic imagingguidelinesheartmortalityantianginal therapyrevascularizationct angiography of coronary arteriesmulti vessel coronary artery diseaseeuropean society of cardiology

Issue Section: ESC guidelines

Collection: ESC PublicationsArticle Contents

2. Introduction

The 2019 ESC (European Society of Cardiology) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes introduced the term chronic coronary syndromes (CCS)1 to describe the clinical presentations of coronary artery disease (CAD) during stable periods, particularly those preceding or following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). CAD was defined as the pathological process characterized by atherosclerotic plaque accumulation in the epicardial arteries, whether obstructive or non-obstructive. Based on expanded pathophysiological concepts, a new, more comprehensive definition of CCS is introduced:

‘CCS are a range of clinical presentations or syndromes that arise due to structural and/or functional alterations related to chronic diseases of the coronary arteries and/or microcirculation. These alterations can lead to transient, reversible, myocardial demand vs. blood supply mismatch resulting in hypoperfusion (ischaemia), usually (but not always) provoked by exertion, emotion or other stress, and may manifest as angina, other chest discomfort, or dyspnoea, or be asymptomatic. Although stable for long periods, chronic coronary diseases are frequently progressive and may destabilize at any moment with the development of an ACS.’

Of note, ‘disease’ refers to the underlying coronary pathology, and ‘syndrome’ refers to the clinical presentation.

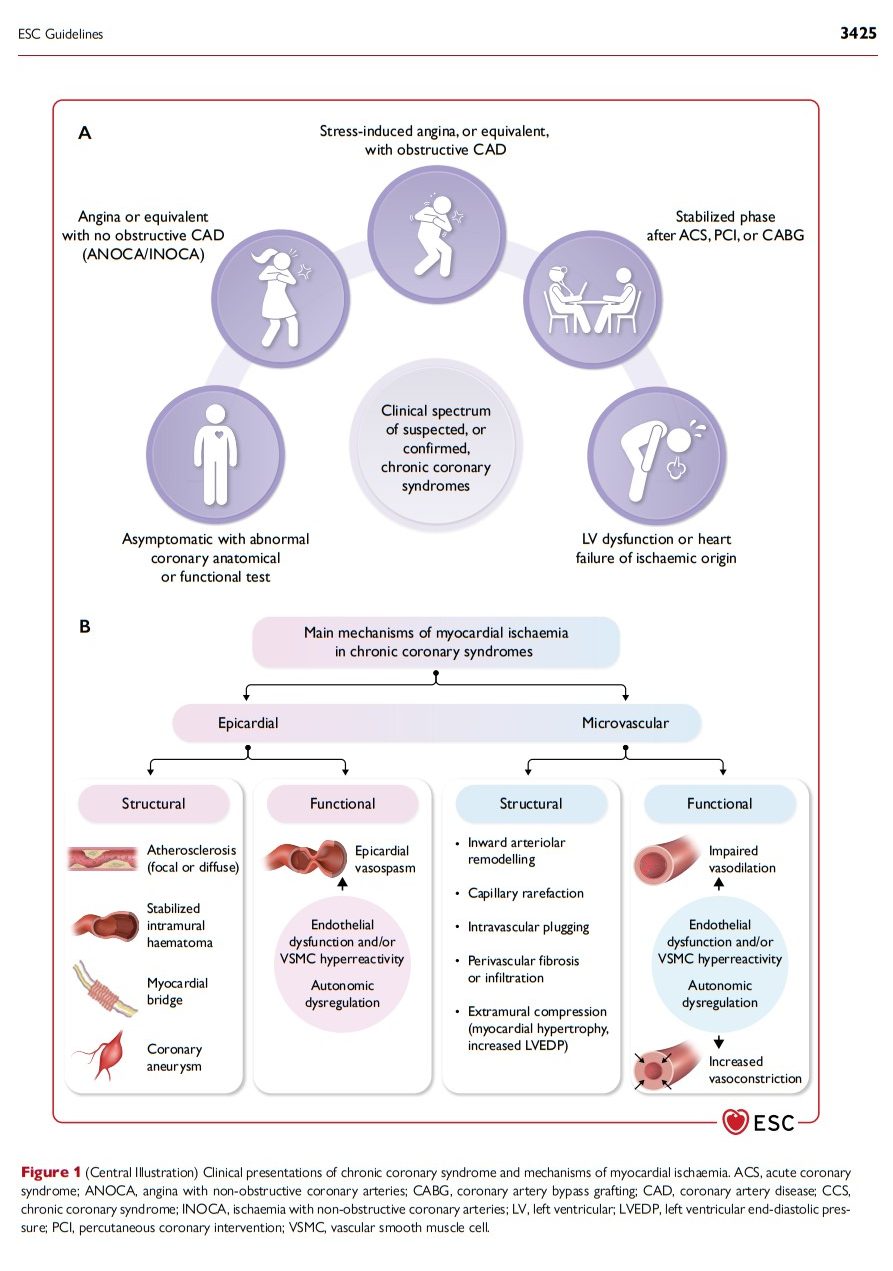

2.1. Evolving pathophysiological concepts of chronic coronary syndromes

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of CCS is transitioning from a simple to a more complex and dynamic model. Older concepts considered a fixed, focal, flow-limiting atherosclerotic stenosis of a large or medium coronary artery as a sine qua non for inducible myocardial ischaemia and ischaemic chest pain (angina pectoris). Current concepts have broadened to embrace structural and functional abnormalities in both the macro- and microvascular compartments of the coronary tree that may lead to transient myocardial ischaemia. At the macrovascular level, not only fixed, flow-limiting stenoses but also diffuse atherosclerotic lesions without identifiable luminal narrowing may cause ischaemia under stress;2,3 structural abnormalities such as myocardial bridging4 and congenital arterial anomalies5 or dynamic epicardial vasospasm may be responsible for transient ischaemia. At the microvascular level, coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is increasingly acknowledged as a prevalent factor characterizing the entire spectrum of CCS;6 functional and structural microcirculatory abnormalities may cause angina and ischaemia even in patients with non-obstructive disease of the large or medium coronary arteries [angina with non-obstructive coronary arteries (ANOCA); ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA)].6 Finally, systemic or extracoronary conditions, such as anaemia, tachycardia, blood pressure (BP) changes, myocardial hypertrophy, and fibrosis, may contribute to the complex pathophysiology of non-acute myocardial ischaemia.7

The risk factors that predispose to the development of epicardial coronary atherosclerosis also promote endothelial dysfunction and abnormal vasomotion in the entire coronary tree, including the arterioles that regulate coronary flow and resistance,8–10 and adversely affect myocardial capillaries,6,11–14 leading to their rarefaction. Potential consequences include a lack of flow-mediated vasodilation in the epicardial conductive arteries9 and macro- and microcirculatory vasoconstriction.15 Of note, different mechanisms of ischaemia may act concomitantly.

2.2. Chronic coronary syndromes: clinical presentations (Figure 1)

In clinical practice, the following, not entirely exclusive, CCS patients seek outpatient medical attention: (i) the symptomatic patient with reproducible stress-induced angina or ischaemia with epicardial obstructive CAD; (ii) the patient with angina or ischaemia caused by epicardial vasomotor abnormalities or functional/structural microvascular alterations in the absence of epicardial obstructive CAD (ANOCA/INOCA); (iii) the non-acute patient post-ACS or after a revascularization; (iv) the non-acute patient with heart failure (HF) of ischaemic or cardiometabolic origin. A further growing category (v) are the asymptomatic individuals in whom epicardial CAD is detected during an imaging test for refining cardiovascular risk assessment,16 screening for personal or professional purposes, or as an incidental finding for another indication.17 Patients may experience a variable and unpredictable course, transitioning between different types of CCS and ACS presentations throughout their lifetime.

The clinical presentations of CCS are not always specific for the mechanism causing myocardial ischaemia; thus, symptoms of dysfunctional microvascular angina (MVA) may overlap with those of vasospastic or even obstructive large–medium artery angina. Furthermore, it is important to note that CCS doesn’t always present as classical angina pectoris and symptoms may vary depending on age and sex. Sex-stratified analyses indicate that women with suspected angina are usually older and have a heavier cardiovascular risk factor burden, more frequent comorbidities, non-anginal symptoms such as dyspnoea and fatigue, and greater prevalence of MVA than men.18–21

2.3. Changing epidemiology and management strategies

Contemporary primary prevention,16 including lifestyle changes and guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), has led to a decline of the age-standardized prevalence22,23 of obstructive epicardial coronary atherosclerosis in patients with suspected CCS.24–28 As a consequence, the diagnostic and prognostic risk prediction models applied in the past to identify obstructive epicardial CAD in patients with suspected angina pectoris have required updating and refinement.27,29,30 Initial use of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA)31,32 for detecting and assessing epicardial coronary atherosclerosis is increasingly being adopted since it has shown similar performance to non-invasive stress testing for detecting segmental myocardial ischaemia.33–35 Invasive coronary angiography (ICA), classically used to detect anatomically significant stenoses, has expanded to become a functional test36 that includes refined haemodynamic assessment of epicardial stenoses, provocative testing for the detection of epicardial or microvascular spasm,37–40 and a functional assessment of CMD.41–43 Moreover, there is a growing interest in non-invasive imaging methods such as stress positron emission tomography (PET)44,45 or stress magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),46 which allow accurate assessment of the coronary microcirculation in a quantitative manner.

Medical therapy for CCS patients, including antithrombotic strategies, anti-inflammatory drugs, statins and new lipid-lowering, metabolic, and anti-obesity agents, has significantly improved survival after conservative treatment, making it harder to demonstrate the benefits of early invasive therapy.47 However, revascularization can still benefit patients with obstructive CAD at high risk of adverse events, not only for symptom relief48–52 but also to prevent spontaneous myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death and, in some groups, to improve overall survival53–56 during long-term follow-up. Recently, revascularization through percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was shown to provide more angina relief than a placebo procedure in patients with stable angina and evidence of ischaemia, on minimal or no antianginal therapy, confirming the beneficial effects of revascularization.52

The present guidelines deal with the assessment and diagnostic algorithm in patients with symptoms suspected of CCS (Section 3) and their treatment (Section 4), special subgroups of CCS patients (Section 5) and finally, long-term follow-up and care (Section 6).

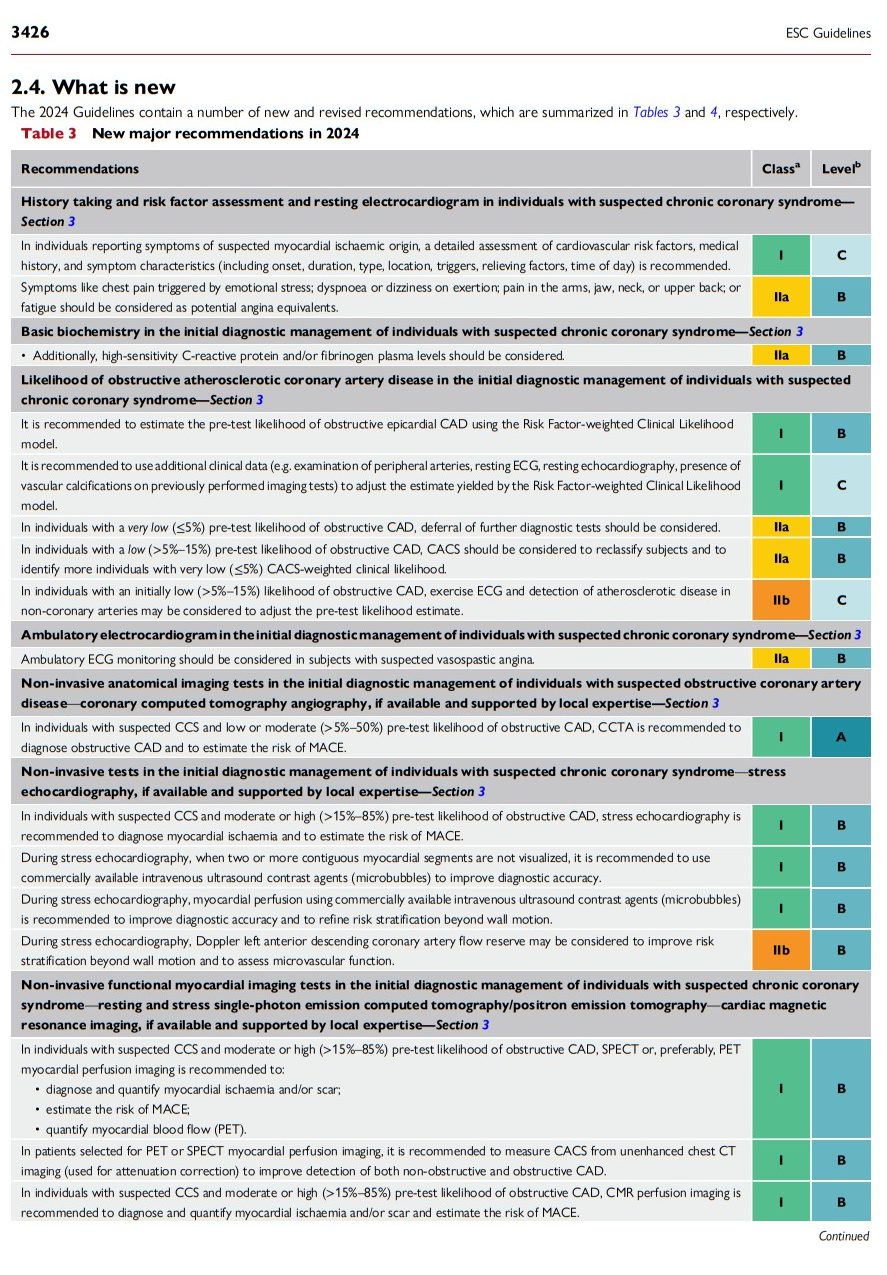

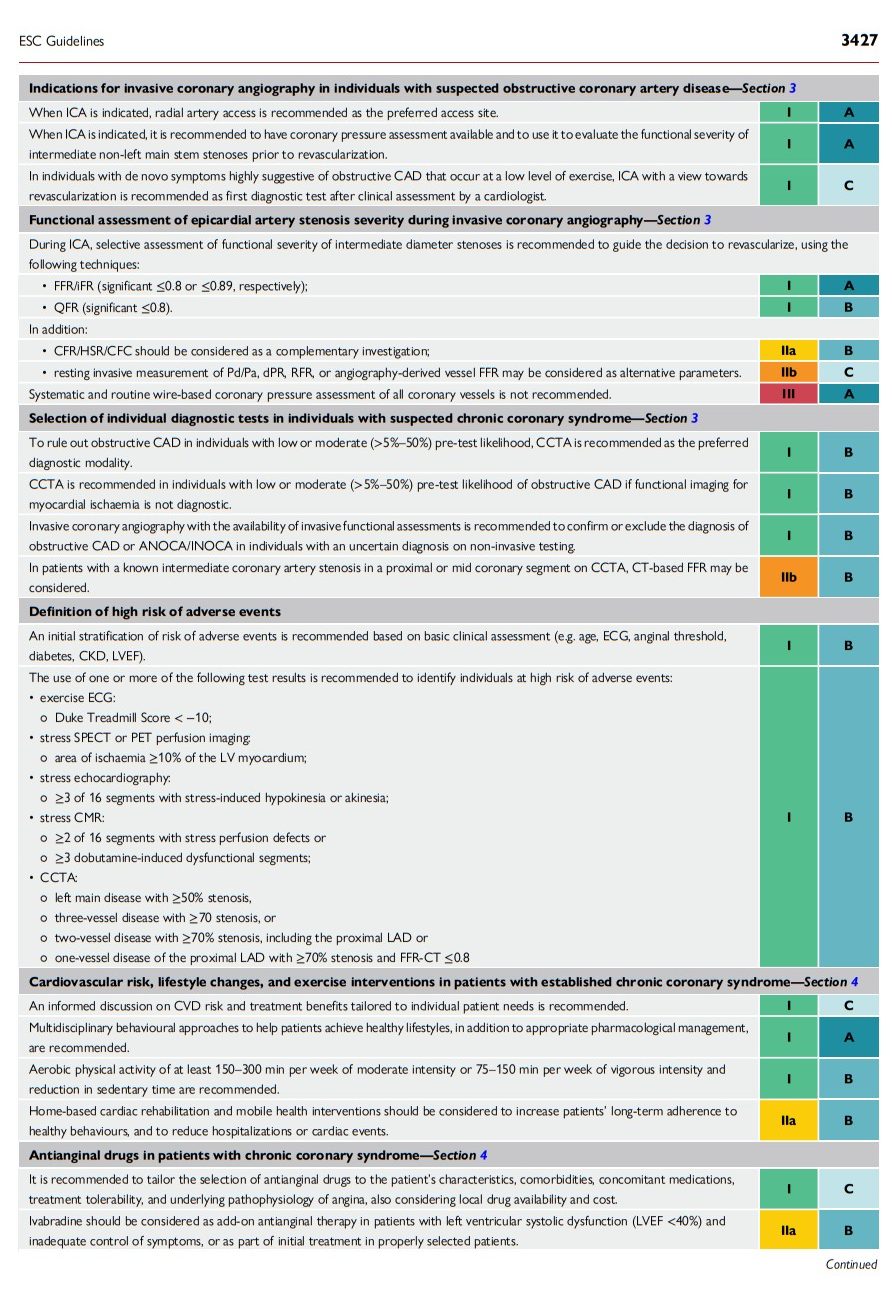

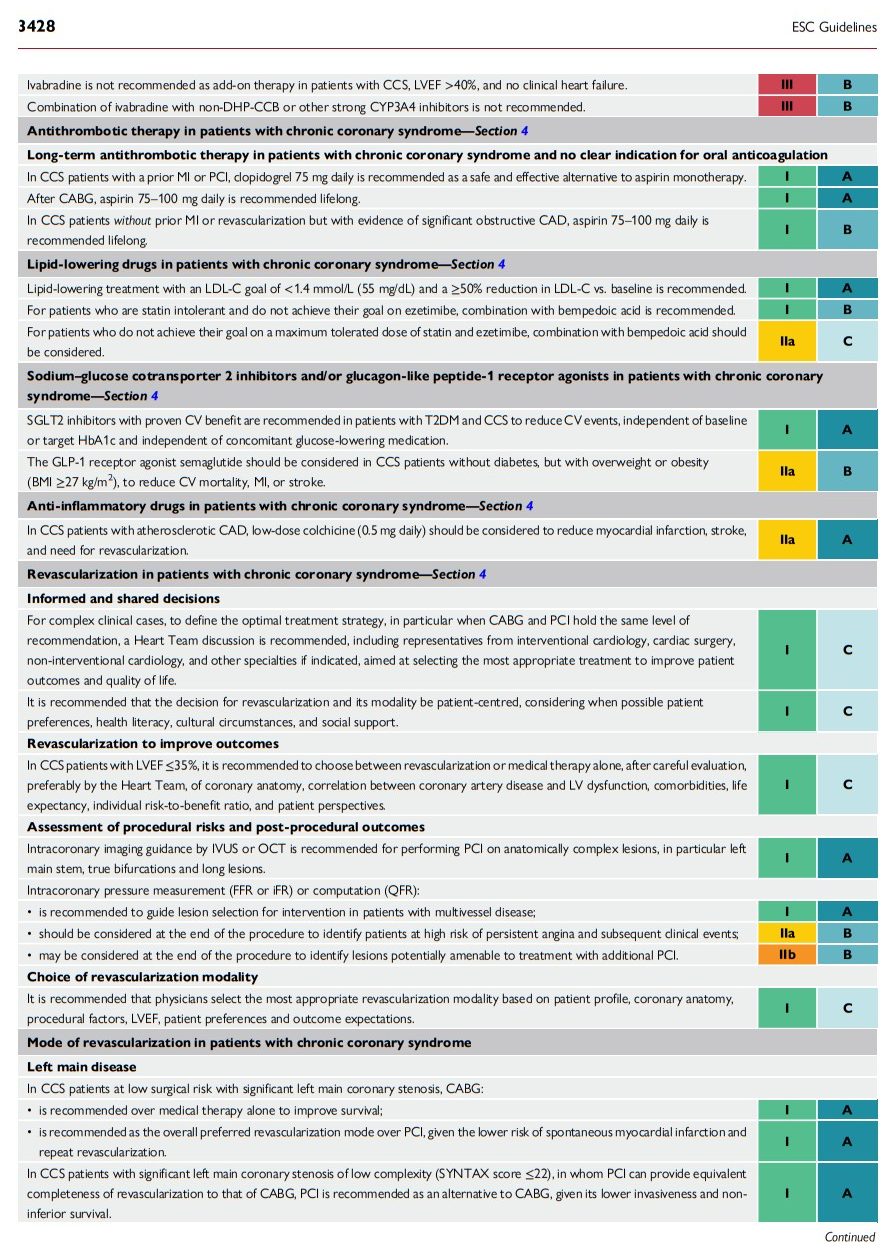

2.4. What is new

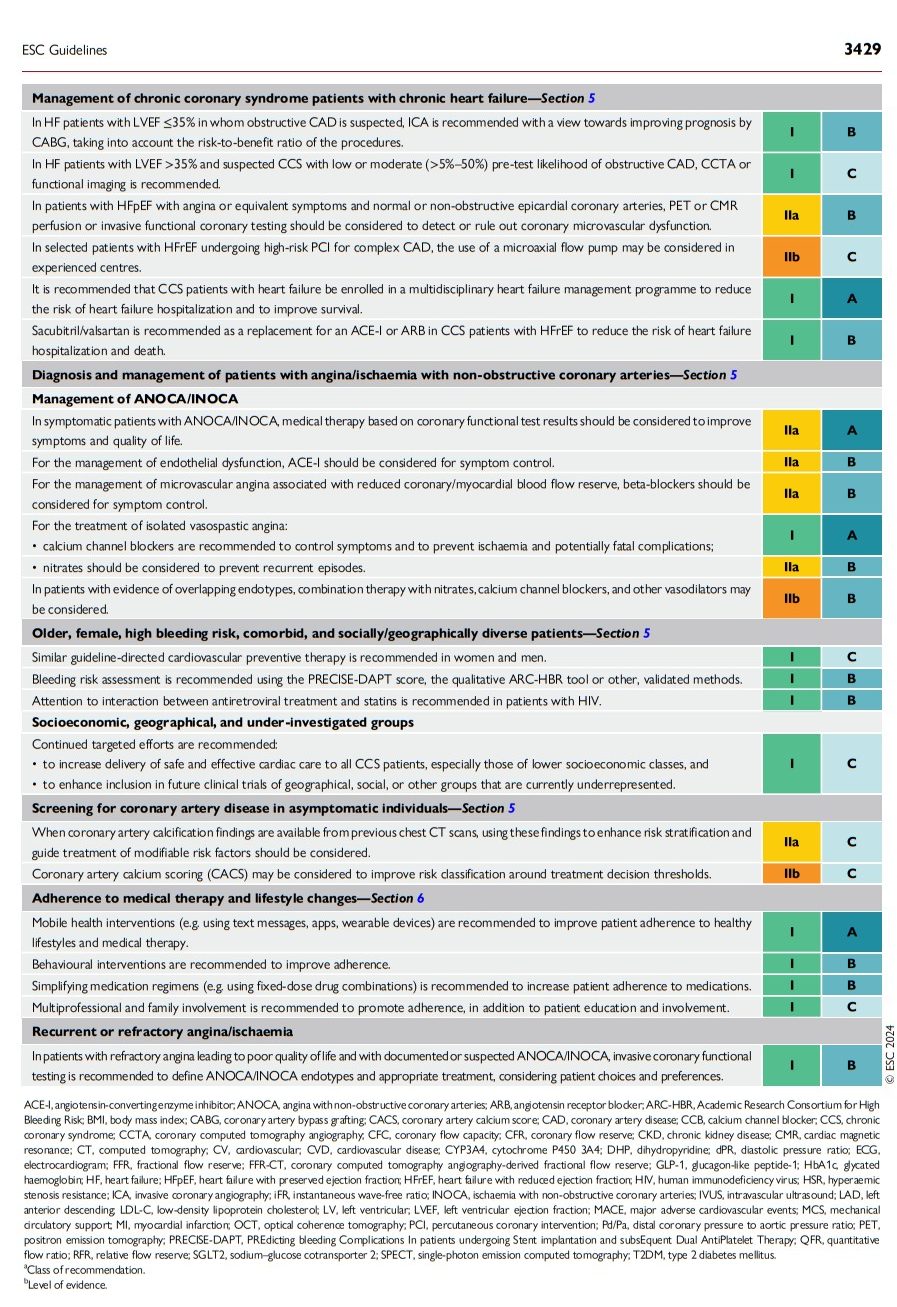

The 2024 Guidelines contain a number of new and revised recommendations, which are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.