In addition to the resource below, please see The Alzheimer’s Association clinical practice guideline for the diagnostic evaluation, testing, counseling, and disclosure of suspected Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (DETeCD-ADRD): Validated clinical assessment instruments. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Alzheimers Dement. 2025 Jan;21(1):e14335. doi: 10.1002/alz.14335. Epub 2024 Dec 23. From the above article see:

- TABLE 1 Validated instruments to assist in the structured reporting of symptoms of cognitive impairment. P 4 of 20.

- TABLE 2 Validated instruments to assist in the assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD/ADRD. P 6 of 20.

- TABLE 3 Validated instruments to assist in the structured assessment of functional impairment in instrumental and basic ADL in patients with cognitive impairment. P 8 of 20.

- TABLE 4 Validated mental status test instruments. P 11 of 20.

- TABLE 5 Comparison of selected brief cognitive tests to detect cognitive impairment or dementia. P 13 of 20.

Today I review, link to, and excerpt from Alzheimer’s Association clinical practice guideline for the Diagnostic Evaluation, Testing, Counseling, and Disclosure of Suspected Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (DETeCD-ADRD): Executive summary of recommendations for primary care [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Alzheimers Dement. 2025 Jun;21(6):e14333. doi: 10.1002/alz.14333. Epub 2024 Dec 23.

In addition to the above article, please review:

There are 101 similar articles in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above article.

- Abstract

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. METHODS

- 3. DISCUSSION

- 4. CONCLUSIONS

- AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

- CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

- Supporting information

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Contributor Information

- REFERENCES

- Associated Data

Abstract

US clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or AD and related dementias (ADRD) are decades old and aimed at specialists. This evidence-based guideline was developed to empower all-including primary care-clinicians to implement a structured approach for evaluating a patient with symptoms that may represent clinical AD/ADRD. Through a modified-Delphi approach and guideline-development process (7374 publications were reviewed; 133 met inclusion criteria) an expert workgroup developed recommendations as steps in a patient-centered evaluation process. This summary focuses on recommendations, appropriate for any practice setting, forming core elements of a high-quality, evidence-supported evaluation process aimed at characterizing, diagnosing, and disclosing the patient’s cognitive functional status, cognitive-behavioral syndrome, and likely underlying brain disease so that optimal care plans to maximize patient/care partner dyad quality of life can be developed; a companion article summarizes specialist recommendations. If clinicians use this guideline and health-care systems provide adequate resources, outcomes should improve in most patients in most practice settings. Highlights US clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or AD and related dementias (ADRD) are decades old and aimed at specialists. This evidence-based guideline was developed to empower all-including primary care-clinicians to implement a structured approach for evaluating a patient with symptoms that may represent clinical AD/ADRD. This summary focuses on recommendations, appropriate for any practice setting, forming core elements of a high-quality, evidence-supported evaluation process aimed at characterizing, diagnosing, and disclosing the patient’s cognitive functional status, cognitive-behavioral syndrome, and likely underlying brain disease so that optimal care plans to maximize patient/care partner dyad quality of life can be developed; a companion article summarizes specialist recommendations. If clinicians use this guideline and health-care systems provide adequate resources, outcomes should improve in most patients in most practice settings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease; Lewy body dementia; cerebrospinal fluid; dementia; diagnosis; frontotemporal dementia; magnetic resonance imaging; mild cognitive impairment; molecular biomarkers; positron emission tomography; vascular cognitive impairment.

© 2024 The Author(s). Alzheimer’s & Dementia published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Alzheimer’s Association.

Highlights

- US clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or AD and related dementias (ADRD) are decades old and aimed at specialists.

- This evidence‐based guideline was developed to empower all—including primary care—clinicians to implement a structured approach for evaluating a patient with symptoms that may represent clinical AD/ADRD.

- This summary focuses on recommendations, appropriate for any practice setting, forming core elements of a high‐quality, evidence‐supported evaluation process aimed at characterizing, diagnosing, and disclosing the patient’s cognitive functional status, cognitive–behavioral syndrome, and likely underlying brain disease so that optimal care plans to maximize patient/care partner dyad quality of life can be developed; a companion article summarizes specialist recommendations.

- If clinicians use this guideline and health‐care systems provide adequate resources, outcomes should improve in most patients in most practice settings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrospinal fluid, dementia, diagnosis, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, magnetic resonance imaging, mild cognitive impairment, molecular biomarkers, positron emission tomography, vascular cognitive impairment 1. INTRODUCTION

A major global health challenge is the timely detection, accurate diagnosis, appropriate disclosure, and proper management of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (ADRD), which include frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Lewy body disease (LBD), vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID), mixed etiology dementias, and others. By mid‐century, the number of Americans living with dementia will more than double from 5.8 to 13.8 million, 1 leading to an explosion of the already exorbitant individual and societal costs and burden. 2 , 3

All too often, cognitive and behavioral symptoms due to AD/ADRD are undiagnosed, undisclosed, or misattributed. 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 A minority of primary care providers (PCPs) report feeling highly confident in making a diagnosis of AD or ADRD, 12 39% of PCPs report “never or only sometimes” being comfortable making a dementia diagnosis, 2 and many PCPs say they lack the tools to care for patients with cognitive problems and rely on specialists (although recognizing the challenges of accessing specialists in many settings). 1 In 50% of individuals with US billing records indicating dementia due to AD or ADRD, the patient or care partner report not being informed of the diagnosis 4 —even though the vast majority want to know their diagnosis— 4 , 13 , 14 , 15 despite evidence supporting individually and societally meaningful medical and psychosocial benefits of timely diagnosis. 3 , 4 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 As a result of delayed diagnosis and disclosure, patients and families experience distressing, costly, and potentially harmful delays in receiving appropriate care. 4 , 17 Barriers to timely and accurate diagnosis and appropriate disclosure of MCI or dementia due to AD/ADRD are multifactorial, but many could be mitigated by the establishment—followed by effective dissemination and implementation—of evidence‐supported clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of suspected MCI or dementia in primary as well as specialty care settings.

This executive summary distills the core elements of a high‐quality, evidence‐supported, patient‐centered evaluation and disclosure process that are appropriate for primary care and any other practice setting. A companion article summarizes recommendations for specialists (Dickerson BC, et al.). 32

2. METHODS

The Alzheimer’s Association convened a multi‐disciplinary DETeCD‐ADRD CPG expert workgroup composed of 10 voting members from primary care, specialty and subspecialty care, long‐term and palliative care, health economics, and bioethics, and retained a team from Avalere Health with expertise in developing clinical appropriate use criteria and practice guidelines.

The process included a systematic review of the published evidence focused on the diagnosis of MCI and dementia likely due to AD based on six PICOTS (patient population/intervention/comparator/outcome/timing/setting) framework questions formulated by the workgroup and was conducted and independently graded by the Pacific Northwest Evidence‐based Practice Center at Oregon Health & Science University.

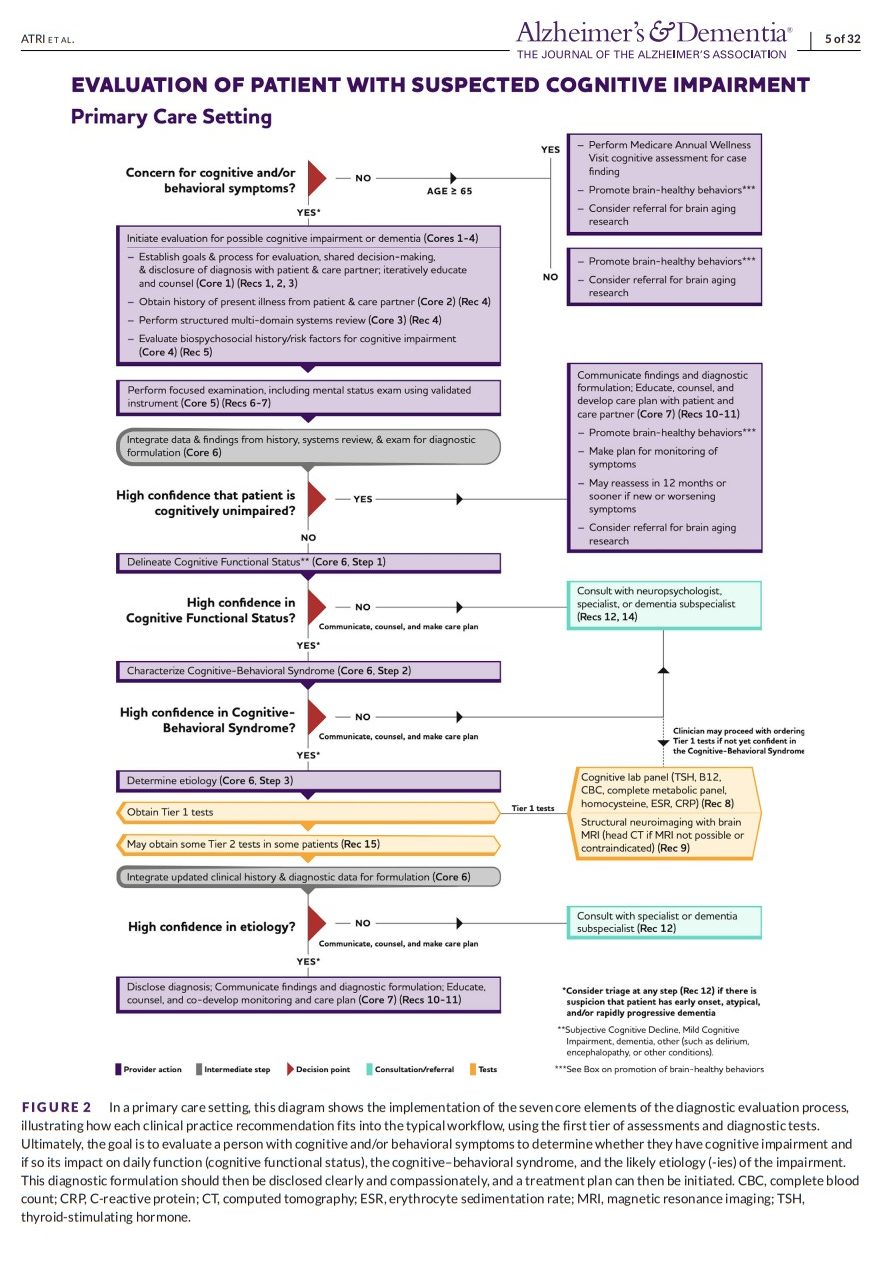

The workgroup attempted to phrase each recommendation as a practical action that is considered one of a series of steps in the evaluation and disclosure process. Recommendations 1 through 11 were purposefully written (and re‐written several times after several rounds of modified‐Delphi discussions and voting by the workgroup) so that they could be assigned the highest strength of recommendation. That is, the benefit of performing the recommended action, as part of the goal‐oriented and dynamic evaluation and disclosure process delineated in Figures 1 and 2, outweighs the potential harm and burden in the majority of circumstances. In so doing, the workgroup sought to describe the fundamental principles and steps of the process of a patient‐centered evaluation that should usually be performed from start to finish.

For patients who may be exhibiting symptoms and/or signs of cognitive impairment due to AD or ADRD, the three steps of the diagnostic formulation may be accomplished by following a process of seven core elements. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Dx, diagnosis; Hx, history.

BOX 1: DETeCD‐ADRD Recommendations

RECOMMENDATION 1: For patients who self‐report or whose care partner or clinician report cognitive, behavioral, or functional changes, the clinician should initiate a multi‐tiered evaluation focused on the problem (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- The timely evaluation of an individual with cognitive or behavioral symptoms concerning for MCI or dementia represents best medical practice.

Considerations for Implementation

- Any middle‐aged or older patient who self‐reports—or whose spouse, family, or other informant (or clinician) reports concern regarding symptoms of cognitive, behavioral, or functional decline—should undergo an evaluation to determine whether they might have a cognitive–behavioral syndrome arising as a result of a specific neuropathology. A clinician should not assume “normality” or ascribe cognitive or behavioral symptoms to “normal aging” without an appropriate evaluation, which would constitute suboptimal care.

- The evaluation process for possible cognitive or behavioral impairment can be initiated and in most cases completed at any of a variety of clinical practice settings: primary care, specialty care, or dementia subspecialty care. The practitioner’s proficiency with this patient population and the profile of the individual patient should guide the evaluation process.

- The evaluation begins with a history from not only the patient but also—importantly—from someone who knows the patient well (an informant).

RECOMMENDATION 2: The clinician should use patient‐centered communication to develop a partnership with the patient or with patient and a care partner to (1) establish shared goals for the evaluation process and (2) assess capacity (understanding and appreciation) to engage in the goal‐setting process for the evaluation (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- Competent, hence ethical, medicine relies on a clinician and patient freely and openly exchanging facts as a foundation to allow a patient to exercise her or his autonomy.

- Clinicians caring for patients with cognitive–behavioral syndromes may face unique challenges arising from impairments that may be present in a patient’s awareness of the illness (anosognosia) or understanding and appreciation of medical facts and the ability to use this information to make decisions about medical care or other important activities (capacity).

- Impairments in awareness and capacity can impact the evaluation process, including the ability to provide accurate information and to fully participate in the goal‐setting process.

- Impairments in awareness and capacity that may be present at the outset or that will arise sooner or later in all patients with dementia due to AD or ADRD dictate the need to engage a care partner in the communication of the diagnosis, usually from the beginning.

Considerations for Implementation

- The clinician should establish a critical triadic clinician–patient–informant/care partner relationship during the evaluation and disclosure process. This relationship seeks to build a strong foundation to establish shared goals, obtain information necessary for an accurate diagnosis, effectively communicate an appropriate explanation of the illness being faced, and help formulate and implement a robust plan of care.

- Throughout the process, the clinician should develop a dialogue with the patient and care partner that uses patient‐centered communication to collaboratively set goals and to adjust them, when necessary, as the process unfolds.

- Throughout the process, the clinician should assess informational and educational needs, capacity, and the impact of the evaluation and disclosure process on the patient and care partner, providing structured information and educational resources, while tailoring the communication of this information to the individuals; the clinician’s assessment of awareness and capacity should guide the timing and content of the information shared with the patient and their care partner.

RECOMMENDATION 3: The evaluation process should use tiers of assessments and tests based on individual presentation, risk factors, and profile to establish a diagnostic formulation, including (1) the overall level of impairment, (2) the cognitive–behavioral syndrome, and (3) the likely cause(s) and contributing factors (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- A structured yet personalized diagnostic evaluation of cognitive or behavioral symptoms—with hierarchical use of tiers of assessments and tests tailored to the patient—balances effectiveness and efficiency.

- This structured yet individualized approach ensures that essential information is collected in all cases while allowing leeway for clinical judgment regarding need for further assessments, tests, or consultative input.

- Ultimately, the clinician will integrate available data to arrive at a confident diagnosis based on established clinical criteria (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4), or to exclude such diagnoses.

- The first step of this three‐step approach to diagnostic formulation is fundamentally important: for the clinician to delineate the patient’s cognitive functional status—the overall level of functional independence or dependence related to their cognitive or behavioral condition (i.e., cognitively unimpaired; subjective cognitive decline; mild cognitive impairment; mild, moderate, severe, or terminal dementia; Table 1). This determination has important implications for the evaluation process and care planning.

- The second step in diagnostic formulation is to characterize the specific clinical profile of the patient’s cognitive–behavioral syndrome (i.e., “syndromic diagnosis”; Tables 2, 3, 4), because this places the patient in an epidemiologic context of prior probabilities of specific disease processes that can cause the syndrome (Tables 2, 3, 4)—influencing next steps in the diagnostic approach—and also heavily impacts symptom management and care planning.

- Although each cognitive–behavioral syndrome is probabilistically more associated with specific neurodegenerative pathologic changes and diseases than others—most clinical syndromes can be caused by more than one type of pathology or disease—the probability/likelihood of a particular syndrome being due to a specific disease is also a function of individual patient demographics, characteristics, and dementia risk factors (e.g., age, developmental and educational history, family history, cerebrovascular risk factors).

- The third step in diagnostic formulation is to establish the most likely brain disease (or condition) causing the clinical syndrome (i.e., “etiological diagnosis”; Tables 2, 3, 4); and to delineate any other conditions or factors that may be contributing to the illness.

Considerations for Implementation

- A structured and individualized approach, detailed in Recommendations 4 to 9, should be used to first attempt to delineate, characterize, and establish the status, syndrome, and likely cause(s) of the illness, which in many patients will be sufficient to allow a highly confident diagnosis to be made. Some patients may require more specialized assessments and tests.

- For a majority of individuals with a typical presentation of dementia due to AD, a first tier of clinical assessments, laboratory tests, and neuroimaging (Figure 2) should be sufficient for the clinician to achieve high probabilistic diagnostic confidence.

- For each individual, the clinician must then decide if sufficient data exist to make a probabilistically confident etiological diagnosis, with reference to established clinical diagnostic criteria (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4), or if additional tests or referrals are needed to achieve the desired level of confidence in the diagnosis. Molecular biomarker confirmation may be desired for a variety of reasons.

- To establish each of the three steps of the diagnostic formulation, in some cases, multiple tiers of assessments or diagnostic testing may need to be pursued, depending on the complexity of the patient, the proficiency of the clinician, and the availability of resources.

- Clinicians should consider that there is substantial variability between patients in the clinical manifestations of cognitive impairment or dementia arising from AD/ADRD which may relate to factors associated with the disease itself, other comorbid conditions, or patient‐specific vulnerability or resilience factors.

- While clinicians should weigh that with increasing age, there is greater likelihood that a patient’s cognitive or behavioral symptoms may result from multiple neurodegenerative brain diseases or comorbidities, a primary driver(s) or cause(s) of the symptoms—a specific primary etiologic diagnosis—that is most likely, should be established and communicated.

RECOMMENDATION 4: During history taking for a patient being evaluated for cognitive or behavioral symptoms, the clinician should obtain reliable information involving an informant regarding changes in (1) cognition, (2) activities of daily living (ADLs and instrumental ADLs [IADLs]), (3) mood and other neuropsychiatric symptoms, and (4) sensory and motor function. Use of structured instruments for assessing each of these domains is helpful (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- The history of present illness (HPI) is the cornerstone of the approach to medical diagnosis. In the evaluation of a patient when a diagnosis of AD or another dementia syndrome is a consideration, the goal of the HPI is to provide a narrative account of the patient’s principal cognitive and behavioral symptoms and their impact on their daily function, and community.

- Careful characterization of symptoms of concern, exploration of plausible relationships between symptoms and pertinent events, and a comprehensive survey of all major domains (cognition, daily function, behavior/neuropsychiatric, sensorimotor) using a structured approach is important for sensitive detection and accurate delineation of potentially clinically relevant changes and syndromes. A structured comprehensive approach is critical because patients and care partners often do not possess the knowledge or vocabulary to represent changes; may not recognize, or may under‐report, misclassify, or misattribute symptoms; and, without a structured approach, busy or distracted clinicians may not inquire about all relevant domains.

Considerations for Implementation

- To obtain the HPI, the clinician should integrate information from an interview with the patient and an informant (care partner) to: (a) characterize the nature of the symptoms about which there is concern; (b) establish the time course of the symptoms (i.e., sequential order of onset, frequency, tempo, and nature of change over time); (c) explore plausible relationships between events and the presenting symptoms (and any potential triggers or contextual features); (d) evaluate impact of symptoms on the patient’s function in activities of daily living, interpersonal relationships, personal and public health and safety, and the need for care partner support.

- In due course, a structured survey of all major domains of cognition, mood/behavior, and sensorimotor function should be performed to try to identify relevant symptoms not volunteered by the patient or informant during the HPI.

RECOMMENDATION 5: During history taking for a patient being evaluated for cognitive or behavioral symptoms, the clinician should obtain reliable information about individualized risk factors for cognitive decline (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- Each person has his or her own individual profile of risk factors—some of which are potentially modifiable (Box 2)—for the underlying brain diseases associated with dementia.

- Each person has a profile of resilience and risk factors that can modify the likelihood, types, and trajectory of cognitive, behavioral, and functional changes associated with neuropathological changes. These factors can also impact the reporting of symptoms and performance on cognitive tests and must be considered uniquely for each individual and informant.

- In older people, cognitive and behavioral symptoms may arise from a combination of several factors, including one or multiple types of neuropathological changes (e.g., AD neuropathologic change with or without Vascular Ischemic Brain Injury or LBD) or contributing conditions (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, use of medications that may impair cognition, mood disorder, high alcohol consumption).

- Some conditions that contribute to cognitive impairment are, to varying amounts, modifiable during the life course.

Considerations for Implementation

- During the evaluation process, the clinician should systematically obtain knowledge regarding the patient’s risk factors for neurodegenerative, cerebrovascular, and other diseases or conditions that may cause brain dysfunction.

- During the evaluation process, the clinician should obtain information about the patient’s reserve and vulnerability profile with regard to cognitive and behavioral function.

- The clinician should integrate this information regarding risk factors into the diagnostic evaluation process to: (a) contextualize symptoms and test performance against the patient’s risk profile; (b) estimate the likelihood that the patient’s symptoms may be due to potential effects of one or more diseases, conditions, or other factors, some of which may require specific diagnostic testing and may be more responsive to intervention than others; (c) incorporate the patient’s risk factor profile into the overall care plan by educating and counseling the patient and care partner regarding modifiable risk factors and likely non‐modifiable processes, developing a plan that includes treatments of specific diseases and conditions, and identifying strategies to mitigate the effects of modifiable risk factors, while promoting brain healthy lifestyles (Box 2).

RECOMMENDATION 6: In a patient being evaluated for cognitive or behavioral symptoms, the clinician should perform an examination of cognition, mood, and behavior (mental status exam), and a dementia‐focused neurologic examination, aiming to diagnose the cognitive–behavioral syndrome (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale and Considerations for Implementation

- If a clinician ascertains a history of symptoms of changes in memory, thinking, reasoning, language, attention, perception, or behavior, a structured examination should be performed that includes a dementia‐focused mental status examination and an elemental neurologic examination.

- In addition to the history discussed in Recommendation 5, the examination enables the clinician to characterize the cognitive–behavioral syndrome if one is present and generate hypotheses about the differential diagnosis of the possible etiology (‐ies).

- The examination may identify signs of neurologic or psychiatric impairment that suggest an atypical cognitive–behavioral syndrome, such as one with prominent sensorimotor, language, perceptual, or behavioral components, which may warrant referral to a specialist.

RECOMMENDATION 7: In a patient being evaluated for cognitive or behavioral symptoms, clinicians should use validated tools to assess cognition (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale and Considerations for Implementation

- While there is no single cognitive assessment instrument that fits all circumstances, the use of a validated instrument to detect cognitive impairment is an invaluable step in the evaluation process for the identification of potentially clinically significant cognitive impairment.

- The interpretation of an individual’s cognitive test score profile (not simply whether performance is below or above a cut‐off score) facilitates accurate detection and diagnosis of the cognitive functional status and cognitive–behavioral syndrome.

- The patient’s performance on a validated brief cognitive test should not be interpreted in isolation but should be carefully integrated with patient’s overall risk profile (Recommendation 6), history of presenting illness (Recommendation 5), and other physical or medical examination and diagnostic findings.

- It is possible that when a concern exists, a validated brief cognitive test may not be sufficiently informative or may not capture mild but clinically significant impairments (e.g., in individuals with extremes of age, education, and intelligence, or in those with complex medical or demographic considerations including language and culture); in such situations a clinician should strongly consider referral to a neuropsychologist or specialist.

RECOMMENDATION 8: Laboratory tests in the evaluation of cognitive or behavioral symptoms should be multi‐tiered and individualized to the patient’s medical risks and profile. Clinicians should obtain routine Tier 1 laboratory studies in all patients (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- A multi‐tiered approach to the selection of laboratory diagnostic tests in a patient with cognitive or behavioral impairment should balance individualized risk factors and medical conditions the patient is known to have or is suspected of having.

- A routine laboratory panel as first‐line diagnostic testing (in conjunction with structural neuroimaging, see Recommendation 9) aids in the recognition and treatment of common comorbid conditions that rarely cause but may often contribute to cognitive or behavioral symptoms.

- Routine first‐line laboratory testing in patients suspected of having AD/ADRD is nearly universally recommended by specialty society practice parameters, and non‐US health authority guidelines, but lack consistency regarding which tests should be included.

Considerations for Implementation

- In all, or almost all, patients with suspected cognitive or behavioral symptoms, the clinician should obtain a basic set of Tier 1 laboratory tests (“cognitive lab panel”; Table 5) that includes complete blood count (CBC) with differential; complete metabolic (e.g., Chem‐20) panel with renal and hepatic panels, electrolytes, glucose, calcium, magnesium, and phosphate; thyroid‐stimulating hormone (TSH); vitamin B12 level; homocysteine level; C‐reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

RECOMMENDATION 9: In a patient being evaluated for a cognitive–behavioral syndrome, the clinician should obtain structural brain imaging to aid in establishing the cause(s). If magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not available or is contraindicated, computed tomography (CT) should be obtained (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- Structural brain imaging is useful to exclude non‐AD/ADRD‐related conditions and for diagnostic inclusion of changes related to AD/ADRD.

- Structural brain imaging may show evidence of regional brain atrophy consistent with AD or another neurodegenerative disease. Absence of such changes does not exclude presence of underlying AD/ADRD pathological changes.

- The regional atrophy pattern on structural brain imaging is often probabilistically associated with a type of neurodegenerative pathologic change, although not specific for only that type of pathologic change.

- Some patients who present with gradually progressive cognitive or behavioral symptoms have a brain tumor or other lesion (e.g., infarct, neuroinflammatory, infectious) that can be readily identified using structural brain imaging.

- Structural brain imaging, particularly MRI, is often very helpful for determining the potential contribution of VCID, including cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Considerations for Implementation

- As part of Tier 1 testing for etiological diagnosis, structural brain imaging should be obtained in almost all patients. When available, brain MRI without contrast provides standard of care for individuals that do not have an absolute or relative contraindication—a head CT should be considered in others.

- An individualized risk–benefit calculus, based on goals, circumstances, and clinical status, should also guide the type and timing of brain imaging. For example, without highly compelling clinical reasons, obtaining neuroimaging in a bed‐bound and non‐communicative individual with longstanding and very severe dementia should be avoided.

- The interpretation of structural brain imaging must also take into consideration the patient’s age, because aging itself can be associated with relatively minimal/mild and diffuse cerebral atrophy, leukoaraiosis (white matter changes, better detected on T2 and fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery MRI sequences), or isolated microhemorrhage (better detected on gradient echo/susceptibility weighted imaging MRI sequences), and indication for the scan (e.g., when a cognitive symptom or disorder is being evaluated), because patterns and extent of atrophy, leukoaraiosis, and microhemorrhage are associated with AD/ADRD and VCID. Cerebral atrophy, leukoaraiosis, or microhemorrhage should not be routinely interpreted as “age related” in a patient with cognitive or behavioral symptoms, particularly if not obviously minimal/very mild and diffuse; instead, in such cases, the extent and pattern should be clearly delineated and clinical correlation should be advised.

- The interpretation of structural brain imaging is often facilitated through a dialogue between the clinicians involved in evaluating the patient and the radiologist who is interpreting the scan.

RECOMMENDATION 10: Throughout the evaluation process, the clinician should establish a dialogue with the patient and care partner about the understanding (knowledge of facts) and appreciation (recognition that facts apply to the person) of the presence and severity of the cognitive–behavioral syndrome. The patient and care partner’s understanding and appreciation of the syndrome guide education, diagnostic disclosure, and methods for communicating and documenting diagnostic findings (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- Competent, ethical medicine relies on a doctor and patient freely and openly exchanging facts to allow a patient to exercise autonomy.

- Clinicians caring for patients with cognitive–behavioral syndromes often face unique challenges arising from impairments in patient capacity (understanding and appreciation of the illness).

- Impairments in capacity, along with the impact of the information, will determine the timing and content of information told to the patient, and the level of involvement of a care partner as the patient’s proxy. While a structured diagnostic disclosure process is recommended, it always has to be tailored to the individual patient and care partner(s). Competent, ethical medicine relies on a doctor and patient freely and openly exchanging facts to allow a patient to exercise autonomy.

Considerations for Implementation

- Clinicians caring for patients with cognitive–behavioral syndromes often face unique challenges arising from impairments in patient capacity (understanding and appreciation of the illness).

- Impairments in capacity, along with the impact of the information, will determine the timing and content of information told to the patient, and the level of involvement of a care partner as the patient’s proxy. While a structured diagnostic disclosure process is recommended, it always has to be tailored to the individual patient and care partner(s).

RECOMMENDATION 11: In communicating diagnostic findings the clinician should honestly and compassionately inform both the patient and their care partner of the following information using a structured process: the name, characteristics, and severity of the cognitive–behavioral syndrome; the disease(s) likely causing the cognitive–behavioral syndrome; the stage of the disease; what can be reasonably expected in the future; treatment options and expectations; potential safety concerns; and medical, psychosocial, and community resources for education, care planning and coordination, and support services (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- The purpose of diagnostic disclosure is to accurately and compassionately explain to the patient and care partner(s) the illness they are facing.

- When a clinician communicates the diagnosis, stage, prognosis, and options for care of an illness, a patient (and care partner) can exercise his/her autonomy.

- A standardized approach to the communication of the diagnosis, stage, and prognosis creates structure so that the clinician conveys a large amount of information in a cohesive and supportive manner and assesses the patient’s understanding and appreciation of the information, engaging in a dialogue to personalize the communication of diagnostic information to the individual(s).

- Diagnostic disclosure for patients with cognitive impairment presents important challenges: a patient may not be able to understand or appreciate the information because of the nature of their impairments including, in some cases, lack of insight. In this case, the involvement of a care partner is critical.

Considerations for Implementation

- The patient and care partner’s informational needs, the patient’s capacity, and the clinician’s judgment about the likely impact of diagnostic information on the patient and care partner will guide the process, content, and timing of the information shared with the patient and their care partner. The clinician should deliver the personalized education necessary for the patient and care partner to understand the diagnosis, its implications, and to develop the foundation for care planning.

- The clinician may decide, based on impairments in the patient’s capacity, to use different methods to disclose the diagnosis to the patient and to the care partner(s).

RECOMMENDATION 12: A patient with atypical findings or in whom there is uncertainty about how to interpret the evaluation, or that is suspected of having an early‐onset or rapidly progressive cognitive–behavioral condition, should be further evaluated expeditiously, usually including referral to a specialist (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale

- Delirium and rapidly progressive dementia (usually defined as developing subacutely within weeks or months) are considered to be urgent medical problems requiring rapid, and in some cases inpatient, evaluation and management.

- Atypical, rapidly progressive or early‐onset (young age of onset, age < 65 years) dementias pose unique diagnostic and care challenges due to the potential for a broad differential diagnosis that may require comprehensive neuropsychiatric evaluation; Tier 3 and 4 studies (see Recommendation 15); and specialist assessment, interpretation, or management.

- Atypical dementia presentations are not uncommon, but symptom recognition and accurate diagnosis are frequently delayed for several years.

- Patients with atypical forms of neurodegenerative dementias may have substantially different care and management needs and considerations regarding safety than patients with typical presentations of dementia due to AD.

- Delays in accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of patients with atypical and early‐onset dementias may cause substantial distress, harm, and costs to patients, families, and society, especially when a patient is working and/or raising children at home.

Considerations for Implementation

- The diagnosis of delirium may be clinically straightforward or may be challenging depending on the presentation and medical context, but in all settings requires urgent or emergent care for diagnosis and management (Box 3).

- The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with rapidly progressive dementia requires urgency and is usually complex, often requiring specialist consultation.

- The evaluation of a patient with atypical or early‐onset cognitive impairment or dementia requires proactive and expedited management by the evaluating clinician and should usually involve prompt specialist referral.

- Atypical examination findings in patients with suspected cognitive–behavioral syndromes may include: (1) attentional impairments difficult to differentiate between dementia and delirium, (2) prominent language or social–behavioral abnormalities, (3) sensory or motor dysfunction of cerebral origin, (4) cognitive performance that may be confounded by high or low educational/occupational attainment.

RECOMMENDATION 13: A specialist evaluating a patient with cognitive or behavioral symptoms should perform a comprehensive history and office‐based examination of cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and neurologic functions, aiming to diagnose the cognitive–behavioral syndrome and its cause(s) (Strength of Recommendation A).

- See Dickerson BC et al. 32 for specialists for rationale and considerations for implementation of Recommendations 13 and 15 through 19.

RECOMMENDATION 14: Neuropsychological evaluation is recommended when office‐based cognitive assessment is not sufficiently informative. Specific examples are when a patient or caregiver report concerning symptoms in daily life, but the patient performs within normal limits on a cognitive examination, or when the examination of cognitive–behavioral function is not normal but there is uncertainty about interpretation of results due to a complex clinical profile or confounding demographic characteristics. The neuropsychological evaluation, at a minimum, should include normed neuropsychological testing of the domains of learning and memory (in particular delayed free and cued recall/recognition); attention, executive function, visuospatial function, and language (Strength of Recommendation A).

Rationale and Considerations for Implementation

- The neuropsychological evaluation may detect very mild but clinically important cognitive impairment which a mental status examination (see Recommendation 6) using brief validated cognitive tests (see Recommendation 7)—such as those done in most office examinations—may not capture.

- The neuropsychological evaluation can provide recommendations for potential further studies and a care plan that considers a patient‐centered profile of strengths and limitations and can inform the differential diagnosis of potential etiologies.

- Neuropsychological evaluation can aid in distinguishing neuropsychiatric disorders from the effects of medical and emotional comorbidities or of confounding patient characteristics such as limited or advanced education or language limitations.

- Neuropsychological evaluation should be considered when a clinician needs to better delineate the cognitive functional status or to define the cognitive–behavioral syndrome or when there are complex psychosocial, medical, or demographic characteristics or significant confounding conditions.

- The referring clinician should provide a consultation question that the neuropsychological evaluation can be structured to answer.

RECOMMENDATION 15: When diagnostic uncertainty remains, the clinician can obtain additional (Tier 2–4) laboratory tests guided by the patient’s individual medical, neuropsychiatric, and risk profile (Strength of Recommendation A).

RECOMMENDATION 16: In a patient with an established cognitive–behavioral syndrome in whom there is continued diagnostic uncertainty regarding cause(s) after structural imaging has been interpreted, a dementia specialist can obtain molecular imaging with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET to improve diagnostic accuracy (Strength of Recommendation B).

RECOMMENDATION 17: In a patient with an established cognitive–behavioral syndrome in whom there is continued diagnostic uncertainty regarding cause(s) after structural imaging with or without FDG PET, a dementia specialist can obtain CSF according to appropriate use criteria for analysis of amyloid beta (Aβ)42 and tau/phosphorylated tau (p‐tau) profiles to evaluate for AD neuropathologic changes (Strength of Recommendation B).

RECOMMENDATION 18: If diagnostic uncertainty still exists after obtaining structural imaging with or without FDG PET and/or CSF Aβ42 and tau/p‐tau, the dementia specialist can obtain an amyloid PET scan according to the appropriate use criteria to evaluate for cerebral amyloid pathology (Strength of Recommendation B).

RECOMMENDATION 19: In a patient with an established cognitive–behavioral syndrome and a likely autosomal dominant family history, the dementia specialist should consider whether genetic testing is warranted. A genetic counselor should be involved throughout the process (Strength of Recommendation A).

BOX 2: Brain‐healthy behaviors

Accruing evidence indicates that there are a variety of potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia. 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 In their report, Livingston et al. identified three mid‐life risk factors for dementia, including hearing loss, hypertension, and obesity. 47 In later life, five potentially modifiable risk factors include smoking, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, and diabetes. Although it is impossible to completely eliminate these risks, estimates suggest that risk could be reduced by ≈ 20% if these factors were adequately addressed. Additional evidence is cited in this report indicating that patients with MCI or dementia may benefit—even after symptoms are clearly present—from brain‐healthy behaviors to reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia. 47 Several ongoing studies are evaluating the efficacy of multifaceted lifestyle interventions as preventative approaches or to treat progressive decline in people with dementia.

Although a small group of studies suggest that primary care clinicians are not aware of this evidence, they have a positive attitude toward the promotion of brain health and would like a risk prediction tool and more time to promote brain health. 49 An evidence‐based consensus 50 recommended that clinicians perform individualized risk assessment and counseling, focusing on the American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7. 44 These include the promotion of four health‐related behaviors: non‐smoking status, physical activity at goal levels, body mass index < 25 kg/m2, healthy diet consistent with current guidelines; and three health‐related factors: untreated blood pressure < 120/< 80 mm Hg, untreated total cholesterol < 200 mg/dL, and fasting blood glucose < 100 mg/dL. Citing substantial evidence, they also recommend the pursuit of cognitively stimulating and rewarding activities. 50 Screening and evaluating for obstructive sleep apnea and excessive alcohol use are also important.

We recommend that primary care clinicians work toward bringing this evidence into their practice by performing a personalized assessment of dementia risk factors in any middle‐aged or older adult and providing counseling on “brain‐healthy behaviors.” 51 In many settings, approaches similar to those taken for diabetes treatment and prevention are worth considering, including the development of a “champion” member of the team who provides a summary of evidence and motivational information. 49 If a patient has sought evaluation for symptoms of cognitive decline and been determined to be cognitively normal or experiencing subjective cognitive decline, clinicians should take the opportunity to engage the patient in promoting brain‐healthy behaviors while continuing to monitor cognitive function longitudinally. 52

TABLE 1.

Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment and dementia.

NIA‐AA diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment 39 Cognitive concern reflecting a change in cognition reported by patient or informant or clinician (i.e., historical or observed evidence of decline over time) Objective evidence of impairment in one or more cognitive domains (i.e., formal or “bedside” testing to establish level of cognitive function in multiple domains) Preservation of independence in functional abilities Not demented DSM‐5 diagnostic criteria for mild neurocognitive disorder 40 Evidence of modest cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual‐motor, or social cognition) based on:

- Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a mild decline in cognitive function; and

- A modest impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment.

The cognitive deficits do not interfere with capacity for independence in everyday activities (i.e., complex instrumental activities of daily living such as paying bills or managing medications are preserved, but greater effort, compensatory strategies, or accommodation may be required). The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of delirium. The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia). NIA‐AA diagnostic criteria for dementia 41 Dementia is diagnosed when there are cognitive or behavioral (neuropsychiatric) symptoms that:

- Interfere with the ability to function at work or at usual activities; and

- Represent a decline from previous levels of functioning and performing; and

- Are not explained by delirium or major psychiatric disorder.

Cognitive impairment is detected and diagnosed through a combination of:

The cognitive or behavioral impairment involves a minimum of two of the following domains:

- Impaired ability to acquire and remember new informationSymptoms include: repetitive questions or conversations, misplacing personal belongings, forgetting events or appointments, getting lost on a familiar route.

- Impaired reasoning and handling of complex tasks, poor judgmentSymptoms include: poor understanding of safety risks, inability to manage finances, poor decision‐making ability, inability to plan complex or sequential activities.

- Impaired visuospatial abilitiesSymptoms include: inability to recognize faces or common objects or to find objects in direct view despite good acuity, inability to operate simple implements, or orient clothing to the body.

- Impaired language functions (speaking, reading, writing)Symptoms include: difficulty thinking of common words while speaking, hesitations; speech, spelling, and writing errors.

- Changes in personality, behavior, or comportmentSymptoms include: uncharacteristic mood fluctuations such as agitation, impaired motivation, initiative, apathy, loss of drive, social withdrawal, decreased interest in previous activities, loss of empathy, compulsive or obsessive behaviors, socially unacceptable behaviors.

DSM‐5 diagnostic criteria for major neurocognitive disorder 40 Evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual‐motor, or social cognition) based on:

- Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a significant decline in cognitive function; and

- A substantial impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment.

The cognitive deficits interfere with independence in everyday activities (i.e., at a minimum, requiring assistance with complex instrumental activities of daily living such as paying bills or managing medications). The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of delirium. The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Abbreviations: DSM‐5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition; NIA‐AA, National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association.

TABLE 2.

Cognitive–behavioral syndromes (syndromic diagnosis) and the differential diagnosis for diseases that cause them (etiologic diagnosis).

Cognitive–behavioral syndrome Major clinical features Differential diagnosis of neuropathologic etiology(ies) Progressive amnesic syndrome (single or multi‐domain) Difficulty with learning and remembering new information, sometimes as the main feature, often accompanied by other features (e.g., executive dysfunction, depression, anxiety) Usually AD Often AD with co‐pathologies (AD + VCID, AD + LBD > AD + VCID + LBD)

Sometimes hippocampal sclerosis, argyrophilic grain disease, pure VCID, pure LBD, TDP‐43 proteinopathy/LATE, PART

Rarely FTLD

Progressive aphasic syndrome (e.g., PPA or progressive aphasic multi‐domain syndrome) Speech and language impairments including word‐finding difficulty (anomia), agrammatism, speech sound errors, impaired repetition (often due to auditory‐verbal working memory impairment), impaired comprehension, impaired reading (alexia), impaired writing (agraphia) Usually logopenic variant PPA is due to AD, less commonly FTLD Usually semantic variant PPA is due to FTLD‐TDP43, rarely FTLD‐tau or AD

Usually non‐fluent variant PPA is due to FTLD‐tau, sometimes FTLD‐TDP43, rarely AD

Progressive visuospatial dysfunction (e.g., posterior cortical atrophy syndrome) Difficulty with visual and/or spatial perception and cognition, often with limb apraxia (difficulty planning or performing learned motor tasks or movements), alexia, agraphia, acalculia, and related cognitive dysfunction localizable to posterior cortical regions Usually AD Sometimes FTLD‐CBD or AD + LBD

Rarely LBD

Very rarely FTLD‐TDP43

Progressive dysexecutive and/or behavioral syndrome (e.g., bvFTD) Changes in executive function (judgment, problem solving, reasoning) with or without apathy or changes in personality or social or emotional behavior Frequently FTLD (FTLD‐tau or FTLD‐TDP43) Frequently AD or AD + VCID

Sometimes FTLD‐PSP, FTLD‐CBD, or VCID

Rarely LBD

Progressive cognitive‐behavioral‐parkinsonism syndrome (e.g., dementia with Lewy bodies syndrome or PDD syndrome) Fluctuating levels of cognitive impairment, recurrent visual hallucinations, spontaneous extrapyramidal motor features and a history of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) Often LBD Often LBD with AD

Sometimes LBD with FTLD or VCID

Rarely FTLD‐CBD or FTLD‐PSP

Progressive cortical cognitive‐somatosensorimotor syndrome (e.g., corticobasal syndrome) Cortical sensorimotor (e.g., limb apraxia) and cognitive difficulties especially including executive dysfunction, with asymmetric rigidity and other motor dysfunction Often CBD Sometimes AD, FTLD‐PSP, FTLD‐Pick’s or FTLD‐TDP43

Rarely LBD

Progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome (e.g., PSP Richardson’s syndrome) Postural instability, supranuclear gaze palsy, with varying degrees of cognitive, behavioral, or other movement symptoms Usually FTLD‐PSP Sometimes FTLD‐CBD

Rarely LBD

Note: The syndromic diagnosis is defined by the nature of the cognitive and/or behavioral domain most prominently impacted. There is a probabilistic—not deterministic—relationship between syndromic diagnosis and etiologic diagnosis. AD neuropathologic changes can be associated with many clinical syndromes; multiple etiologies are likely in individuals older than 85 years. VCID may be the primary etiology or a contributor to a host of syndromes. 31 , 42 Korsakoff’s syndrome, limbic encephalitis, anoxic brain injury, traumatic brain injury, temporal lobe epilepsy, sequelae of herpes encephalitis may cause amnesic syndromes but are usually distinguishable by history. In addition, cognitive–behavioral impairment may be a feature of other rare diseases including Huntington’s disease, FTD with ALS, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, multiple‐system atrophy, etc.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease (referring specifically to the neuropathologic changes); bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (referring specifically to the neuropathologic changes; many neuropathologists consider FTLD‐tau to include the neuropathologic entities of Pick’s disease, PSP, and CBD); LATE, limbic‐predominant age‐related TDP‐43 encephalopathy; LBD, Lewy body disease (referring specifically to the neuropathologic changes); PART, primary age‐related tauopathy; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; PPA, Primary Progressive Aphasia; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; VCID, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia.

TABLE 3.

NIA‐AA core diagnostic criteria for probable AD dementia 41 and for MCI due to AD, 39 and AA diagnostic criteria for AD. 80

Diagnostic criteria for AD NIA‐AA core diagnostic criteria for probable AD dementia A diagnosis of probable AD dementia can be made when the patient

A. Insidious onset: symptoms have a gradual onset over months to years, not sudden over hours or days; B. Clear‐cut history of worsening of cognition by report or observation; and C. The initial and most prominent cognitive deficits are evident on history and examination in one of the following categories:

D. The diagnosis of probable AD dementia should not be applied when there is evidence of

Biomarker evidence may increase the certainty that the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome is the AD pathophysiological process. If biomarkers of both Aβ (PET or CSF) and neuronal injury (structural brain MRI, FDG PET, CSF tau) are present, likelihood is high that dementia is due to AD. If both are absent, the dementia is highly likely not due to AD. If they are conflicting, likelihood is intermediate. NIA‐AA core diagnostic criteria for MCI due to AD

- Cognitive concern reflecting a change in cognition reported by patient or informant or clinician (i.e., historical or observed evidence of decline over time)

- Objective evidence of impairment in one or more cognitive domains, typically including memory (i.e., formal or bedside testing to establish level of cognitive function in multiple domains)

- Preservation of independence in functional abilities

- Not demented

Supportive

- Evidence of longitudinal decline in cognition, when feasible

- Rule out vascular, traumatic, medical causes of cognitive decline, where possible

- Report history consistent with AD genetic factors, where relevant

Likelihood of MCI being due to AD

- High: biomarkers of both amyloid‐beta (PET or CSF) and neuronal injury (structural brain MRI, FDG PET, CSF tau) are present

- Intermediate: a biomarker of either amyloid‐beta or neuronal injury is present and the other is untested; or one is positive and one is negative

- Low: biomarkers of both Aβ and neuronal injury are absent

AA diagnostic criteria for AD * Biomarker categorization

Core AD biomarkers

Non‐specific processes involved in AD pathophysiology

Biomarkers of non‐AD pathology

Biological staging (e.g., by PET)

Clinical staging for individuals on the AD continuum

- Stage 0 (asymptomatic, deterministic genetic abnormality, no biomarker abnormality)

- Stage 1 (asymptomatic, biomarker evidence for AD)

- Stage 2 (Transitional cognitive/behavioral decline (including subjective cognitive decline))

- Stage 3 (MCI)

- Stage 4 (mild dementia)

- Stage 5 (moderate dementia)

- Stage 6 (severe dementia)

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AA, Alzheimer’s Association; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NIA, National Institute on Aging; PET, positron emission tomography; p‐tau, phosphorylated tau.

* As this manuscript was in press, an international working group published an alternative proposal for contemporary clinical diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease, maintaining the tradition of viewing it as a clinical‐biological construct. 73TABLE 4.

Diagnostic criteria for major forms of non‐AD dementia (AD‐related dementia).

Diagnostic criteria for various types of ADRD Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia 81 Primary progressive aphasia a 40 , 82 Dementia with Lewy bodies/Parkinson’s disease dementia 40 , 83 Vascular dementia/vascular cognitive impairment 40 , 84 , 85 , 86 LATE 87 Progressive supranuclear palsy 88 Corticobasal degeneration 89 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with frontotemporal dementia 90 Huntington’s disease 91 , 92 Creutzfeldt‐Jacob disease 93 Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LATE, Limbic‐predominant Age‐related TDP‐43 encephalopathy; PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

a PPA can be an atypical presentation of AD, especially when characteristics are consistent with the logopenic variant of PPA.2.2.2. Core elements two through five: history, systems review, risk profile, and exam

Recommendations 4 through 7 provide guidance regarding the next four core elements of the evaluation process, including the use of a structured approach to obtain history and systems review information in the key domains of cognition, daily function, mood and behavior, and sensorimotor function, representing not only the patient’s perspective but in most cases also reliable collateral information from an informant. These recommendations also emphasize the importance of eliciting personalized information regarding risk factors for cognitive decline. The clinician should perform a mental status examination that assesses cognition, mood and behavior, and a dementia‐focused neurologic examination, using validated tools whenever feasible. A separate article in this special issue provides detailed descriptions of instruments that can be used to facilitate these assessments (Atri A, et al). 94 It is also fundamentally important to consider psychiatric history and psychiatric disorders in the differential diagnosis in patients with cognitive impairment, recognizing that it is not uncommon for neurologic diseases to present with primary psychiatric symptoms (Box 3).

BOX 3: Psychiatric disorders and dementia

start here.