Note to myself and to my readers: Although today’s article is outstanding, clinicians need only review the following which occurs at the end of this comprehensive article.

SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND APOB TARGETS

The totality of data suggests that apoB may be a superior marker not only of risk of ASCVD but also of the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy compared with LDL-C. ApoB testing has practical benefits, including that patients do not need to fast, and is more accurate than LDL-C testing in patients with high triglyceride or very low LDL-C levels. Guidelines are increasingly recommending more aggressive lipid reduction; therefore, obtaining precise lipid measurements is essential. This has led many to call for the preferential use of apoB over LDL-C testing. However, consistent recommendations for how clinicians should use apoB results are lacking, and different guidelines have provided variable apoB targets for given LDL-C levels.Some guidelines have compared population- or study-specific percentiles of LDL-C and apoB to identify equivalent levels. Whereas this approach has a benefit of potentially identifying similar numbers of individuals for treatment, variability across populations in the distribution of LDL-C and apoB could lead to continued variability in global guidelines for optimal apoB targets. Discordance analyses have confirmed that people with metabolic syndrome or hypertriglyceridemia are at highest risk of discordantly high apoB levels and reinforce current guideline recommendations to measure apoB in these populations. However, variability across analyses in how discordance was defined limits their use in guiding clinical management. Nevertheless, all discordance analyses demonstrated that regardless of LDL-C levels, those with elevated apoB levels are at increased risk of ASCVD, reinforcing the importance of measurement of apoB.Percentage Reductions in ApoB

Given this, trial data appear to be most useful in developing clinical recommendations for how to implement apoB data to guide treatment recommendations. In terms of proportional reduction, all the lipid-lowering therapy included appeared to reduce apoB levels slightly less than LDL-C levels. Thus, if targeting a ≥50% LDL-C reduction (as recommended by many guidelines) with statins, ezetimibe, PSCK-9i, inclisiran, or bempedoic acid, a comparable apoB reduction would be 40% to 45%.ApoB Treatment Targets

To guide treatment targets, the trial data provide a straightforward path. Because the on-treatment LDL-C levels and on-treatment apoB levels were nearly identical, the same number can be used for apoB as LDL-C. Thus, if a target LDL-C level is <70 mg/dL, the target apoB level should also be <70 mg/dL (0.70 g/L). In high-risk patients with a target of LDL-C level <55 mg/dL, the corresponding goal for apoB should be <55 mg/dL (0.55 g/L). This simple approach can be communicated easily to patients and treating physicians and could eliminate confusion between guidelines.CONCLUSIONS

ApoB testing offers a standardized, accurate, and cost-effective measurement of the total number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles in plasma, providing a more accurate assessment of ASCVD risk and effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapy. Unlike LDL-C testing, apoB testing is particularly advantageous in patients with discordant lipid profiles, such as those with high triglyceride levels, or in patients with insulin resistance, who are more likely to have cholesterol-depleted apoB particles. ApoB testing is also more accurate when the levels of LDL-C are lower, a common situation in clinical practice when guidelines suggest more aggressive treatment targets. Despite this, apoB testing faces barriers to widespread adoption in clinical practice, primarily due to the absence of consistent guidance on its interpretation and application. To address these challenges and on the basis of evidence in RCTs, this review suggests the use of the same number for LDL-C as for apoB when establishing treatment targets. Simplification of the interpretation of apoB values, by aligning apoB targets with LDL-C levels, could enhance its integration into routine practice. The use of apoB levels in clinical decision-making holds promise for more accurate ASCVD risk prediction and tailored lipid-lowering strategies.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Today, I link to and excerpt from Circulation‘s Apolipoprotein B: Bridging the Gap Between Evidence and Clinical Practice. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Circulation. 2024 Jul 2;150(1):62-79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.068885. Epub 2024 Jul 1.

There are 101 similar articles in PubMed.

The above article has been cited 21 times in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

Despite data suggesting that apolipoprotein B (apoB) measurement outperforms low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level measurement in predicting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, apoB measurement has not become widely adopted into routine clinical practice. One barrier for use of apoB measurement is lack of consistent guidance for clinicians on how to interpret and apply apoB results in clinical context. Whereas guidelines have often provided clear low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets or triggers to initiate treatment change, consistent targets for apoB are lacking. In this review, we synthesize existing data regarding the epidemiology of apoB by comparing guideline recommendations regarding use of apoB measurement, describing population percentiles of apoB relative to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, summarizing studies of discordance between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and apoB levels, and evaluating apoB levels in clinical trials of lipid-lowering therapy to guide potential treatment targets. We propose evidence-guided apoB thresholds for use in cholesterol management and clinical care.Lipid measurement is performed with the main goal of identifying and treating individuals with or at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1 Cholesterol circulates in plasma within lipoprotein particles, of which apolipoproteins are essential structural and functional components. There are 2 main isoforms of apolipoprotein B (apoB) found on lipoproteins: apoB48, which is present in lipoproteins of intestinal origin, including chylomicrons and chylomicron remnants; and apoB100, which is found in lipoproteins of hepatic origin, including very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and lipoprotein(a).2 Chylomicrons are too large to enter the arterial wall, but the other apoB-containing lipoproteins, including chylomicron remnants, can be trapped in the arterial wall and deposit cholesterol, therefore driving the atherogenesis process.3 High-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles do not contain apoB. Because each atherogenic lipoprotein particle only contains 1 molecule of apoB, plasma apoB measurement provides a measurement of the total number of atherogenic particles in plasma (Figure 1).4Figure 1. Schematic illustration of apolipoprotein B48-containing and apolipoprotein B100-containing lipoproteins. apoB indicates apolipoprotein B; IDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) particles derived from the VLDL lipolysis contain different types of lipids and proteins, including apoB, in a micelle-like arrangement (Figure 1). Different types of assays have been developed to quantify LDL in plasma, the most widely used being LDL-C, which quantifies the amount of cholesterol carried collectively by the LDL lipoproteins.5All atherogenic lipoproteins, including VLDL and LDL, contain a single apoB molecule (Figure 1). In accordance, measurement of apoB provides a direct assessment of the number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles. The use of apoB clinically, however, remains low. Rather, mass-based estimates of LDL-C (the total mass of cholesterol carried collectively by all LDL particles) have been, and remain, the primary measure used to guide treatment.6–11 LDL-C level can be measured directly with ultracentrifugation, but is usually calculated indirectly on the basis of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride levels using one of several formulas.There are multiple reasons for using apoB clinically. Although LDL-C and apoB levels are highly correlated, a large body of previous research indicates that apoB is a better predictor of ASCVD risk than LDL-C for several reasons.3,12,13 First, the cholesterol mass per LDL particle is variable, as shown in Figure 2, which can lead to cholesterol-depleted or cholesterol-enriched lipoproteins that vary in their atherogenicity. People with large numbers of cholesterol-depleted lipoproteins (and a high apoB level) may have an apparently low LDL-C level despite being at higher risk of ASCVD.14 In addition, patients may have high LDL-C levels but low apoB levels because of the presence of cholesterol-enriched lipoproteins. In these patients, ASCVD risk is overestimated by LDL-C levels.2 Second, LDL-C measurements fail to capture the risk conferred by VLDL and IDL particles, which are also atherogenic.15 As illustrated in Figure 2 with 2 hypothetical cases, patients with the same level of LDL-C can have different risk profiles on the basis of the number of atherogenic particles in plasma, illustrating the importance of measuring apoB level.Figure 2. Cholesterol mass and particle measures. Hypothetical representation of 2 patients with the same low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level but different apolipoprotein B (apoB) levels. The patient with higher apoB level has more atherogenic particles and therefore greater cardiovascular risk. VLDL indicates very low-density lipoprotein.Another reason for using apoB clinically is that it does not have the same challenges related to measurement as LDL-C. LDL-C level is usually estimated from total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglyceride levels, based on a formula. The most commonly used formula—the Friedewald equation—has known limitations, particularly in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Newer formulas, including the Martin/Hopkins equation and the Sampson method, have been proposed, but uncertainty remains about the ideal method. Furthermore, all methods have limited performance at very low levels of LDL-C, which is now increasingly common with the introduction of novel lipid-lowering therapies,16–18 and in the presence of severe hypertriglyceridemia, in which fasting LDL-C measurements are recommended.19 In contrast, the measurement of apoB is standardized, accurate, and inexpensive, and can be applied on automated chemistry platforms that are widely available in clinical laboratories.20 The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and the World Health Organization endorsed the standardization of apoB measurement in 1994, introducing a reference material that minimized variability across laboratories.21 Nevertheless, to further enhance the standardization, there are ongoing efforts to develop a new Reference Measurement System using direct apoB measurement through mass spectrometry.22ApoB is unaffected by fasting state. Although the apoB immunoassay measures both apoB100 (which is found on VLDL, IDL, and LDL particles) and apoB48 (which is found on chylomicrons), even in a postprandial state, the number of chylomicrons relative to apoB100-containing particles is low.10 On average, there are 9 LDL apoB100 particles for every VLDL apoB100 particle. Likewise, there are 9 VLDL apoB100 particles for each apoB48 particle. This ratio underlines why total apoB, even in a postprandial state, essentially equates to total apoB100 and is largely unaffected by fasting.3In epidemiologic studies, apoB outperforms LDL-C to predict ASCVD. The first evidence that apoB serves as a more precise indicator of risk emerged in 1980, with a study showing that apoB, particularly LDL apoB, more effectively distinguished between patients with and without coronary atherosclerosis.23 Since then, the evidence supporting superiority of apoB has grown substantially. A meta-analysis by Sniderman et al24 of 12 epidemiologic studies containing estimates of relative risk of ischemic cardiovascular events of different lipid markers found that apoB was the most potent marker of cardiovascular relative risk ratio compared with non-HDL. In addition, changes in apoB may better capture the potential benefit of lipid-lowering therapy. A meta-analysis of 29 randomized clinical trials involving 332 912 patients taking lipid-lowering therapy (statins, ezetimibe, PSCK9 inhibitors, cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors, fibrates, niacin, or n-3 fatty acids) demonstrated that absolute reduction in apoB was associated with decreased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (relative risk for every 10 mg/dL decrease in apoB, 0.95 [0.92–0.99] and 0.93 [0.88–0.98], respectively).25 Moreover, Thanassoulis et al,26 using a frequentist and a Bayesian approach with data from 7 placebo-controlled statin trials, found that mean relative risk reduction of cardiovascular events per standard deviation change in lipid marker from statin therapy was more closely related to reductions in apoB than to reductions in either non–HDL-C or LDL-C. In ODYSSEY-Outcomes (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With Alirocumab), achieved levels of LDL-C or non–HDL-C were not predictive of major adverse cardiovascular events after taking achieved apoB into account.18 Data from other trials have also supported the superiority of apoB over LDL-C as predictor of cardiovascular events. For example, an analysis that included individuals from the UK Biobank (primary prevention cohort) and FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk) and IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial; secondary prevention cohort) demonstrated that apoB was the only lipid measure independently associated with incident myocardial infarction.13 The risk captured by apoB was independent from the type of lipid (cholesterol or triglycerides) or lipoprotein (either LDL or triglycerides-rich, such as VLDL and IDL) across both cohorts.13 Furthermore, data from the Copenhagen General Population Study showed that in statin-treated patients, apoB was a superior marker for all-cause mortality risk than both non–HDL-C and LDL-C.27Using non–HDL-C instead of LDL-C can help improve risk prediction by capturing the burden of non-LDL, apoB-containing lipoproteins, such as VLDL and IDL particles. However, in a large proportion of individuals (ranging between 8% and 23%), apoB and non–HDL-C remain discordant, and apoB remains a better predictor of ASCVD risk.28 Welsh et al,29 analyzing data from the UK Biobank of patients without cardiovascular disease and not taking statins, found that 18% of participants had discordant apoB and LDL-C values (defined as ≥10% absolute difference in baseline percentile of direct LDL and apoB). In those patients, apoB was associated with increased ASCVD risk (adjusted hazard ratio per SD, 1.23 [1.12–1.35]; P<0.001), but directly measured or calculated LDL-C (by either Friedewald or Martin-Hopkins formula) or non–HDL-C were not.Measurement of apoB levels is also needed for accurate differential diagnosis and targeted treatment of hypertriglyceridemia (ie, to differentiate hypertriglyceridemia attributable to excess VLDL particles from hyperchylomicronemia).30 Furthermore, for the identification of familial dysbetalipoproteinemia, also known as type III hyperlipoproteinemia, apoB measurement is necessary. This is a highly atherogenic and treatable dyslipoproteinemia characterized by elevated levels of both cholesterol and triglycerides attributable to a substantial increase in cholesterol-rich chylomicron and VLDL remnant lipoprotein particles.30 Using apoB alongside a traditional lipid panel allows for the reliable diagnosis of type III hyperlipoproteinemia and its differentiation from mixed hyperlipidemia.31HOW HAVE GUIDELINES INCORPORATED APOB?

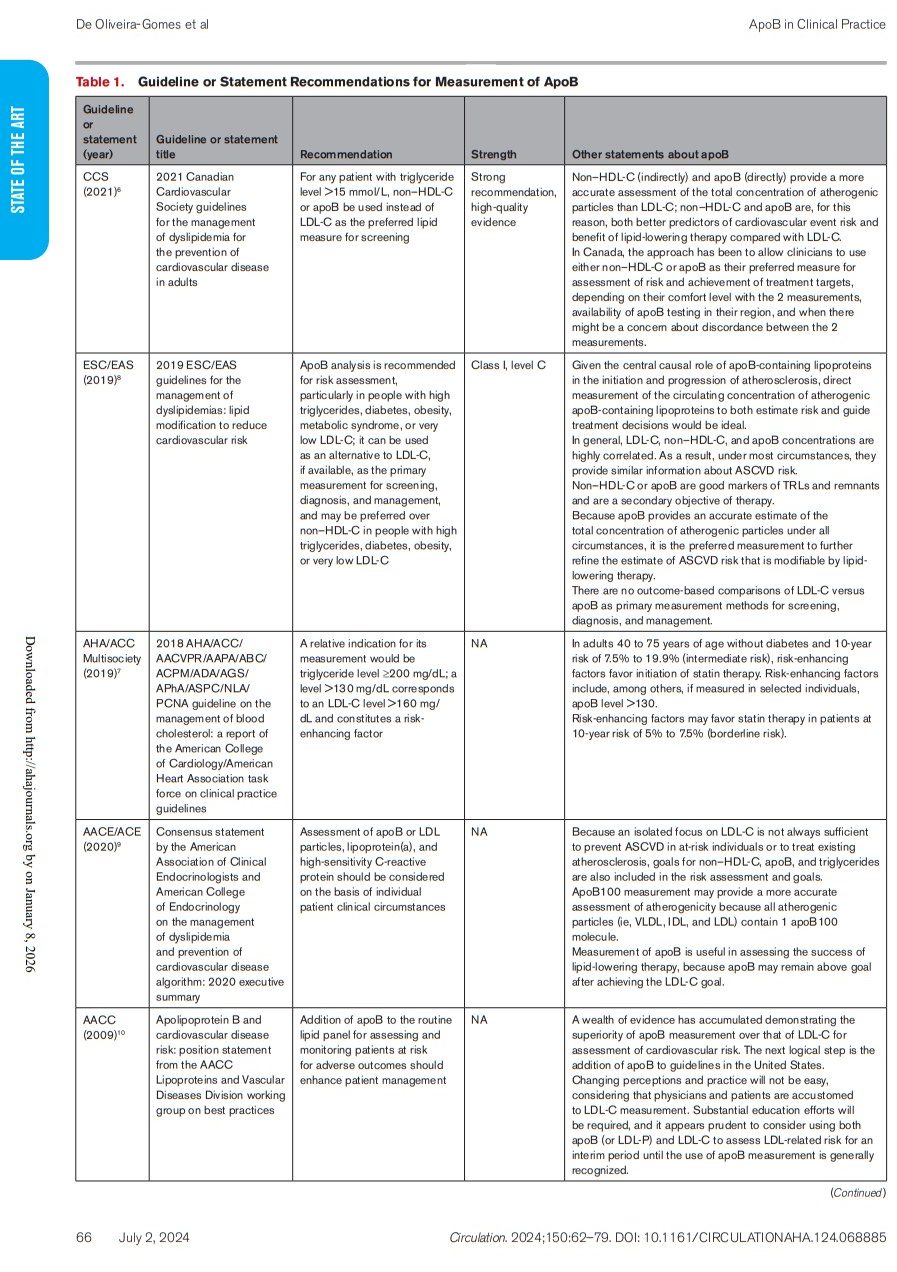

ApoB Measurement

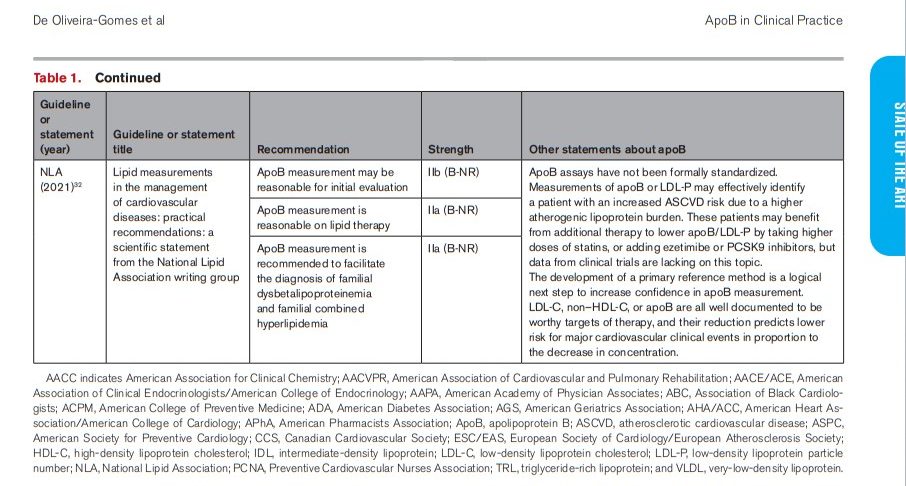

Although major clinical guidelines on management of blood cholesterol levels focus on LDL-C, measurement of apoB is increasingly recommended in certain populations, particularly those with elevated triglyceride levels.6,8 Specific apoB measurement recommendations and statements about apoB measurement by the principal lipid guidelines are shown in Table 1.Canadian and European guidelines have recommended apoB measurement in certain populations for many years. Since 2012, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia has recognized the use of measuring apoB levels in people with high triglyceride levels (defined as triglyceride levels >1.5 mmol/L [131 mg/dL] in the CCS guideline).33 In the most recent guideline (from 2021), the CCS strongly recommended using either apoB or non–HDL-C instead of LDL-C as the preferred lipid measure for screening in any patient with triglyceride levels >1.5 mmol/L (133 mg/dL).6 The guideline further recognized that there could be discordance between apoB and non–HDL-C levels in some patients, and suggested that the decision on which to use should be guided by availability and clinical expertise. Meanwhile, since 2016, the European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) have recommended considering apoB levels, when available, in patients with high triglyceride levels, and expanded this recommendation in the 2019 guideline.8,34 In this most recent document, ESC/EAS recommended apoB measurement as an alternative to LDL-C measurement (and possibly even preferred over non–HDL-C measurement) as the primary marker for screening, diagnosis, and management in people with high triglyceride levels, diabetes, obesity, or very low LDL-C levels (Class I; Level of Evidence C). The 2019 ESC/EAS guideline stated that in the aforementioned individuals, LDL-C levels may underestimate ASCVD risk by underestimating both the total concentration of cholesterol carried by LDL and the total concentration of apoB-containing lipoproteins. Compared with Canadian and European guidelines, American guidelines have been more limited in recommending measurement of apoB.7 One of the oldest recommendations for use of apoB measurement in the United States comes from the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, whose 2009 Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division working group on best practices statement supported the use of apoB measurement for assessing and monitoring patients at risk for cardiovascular disease. In that statement, the authors noted that “changing perceptions and practice will not be easy, considering that physicians and patients are accustomed to LDL-C. Significant education efforts will be required.”10 Indeed, over the subsequent decade, LDL-C remained the main recommended measure of lipid-related risk by US guidelines. The 2018 multisociety guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, in collaboration with multiple leading medical organizations, stated that those with triglyceride levels ≥200 mg/dL have a “relative indication” for apoB measurement.7 The guideline also states that an apoB level >130 mg/dL should be considered a “risk-enhancing factor” for considering lipid-lowering therapy, but does not recommend universal testing. The 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guideline stated that apoB may provide a more accurate assessment of atherogenicity, because apoB levels can be elevated in individuals with normal LDL-C levels, particularly in those with insulin resistance, who often could have small dense LDL.9 It also recognized that apoB is useful in assessing the success of lipid-lowering therapy, because apoB level may remain above the goal after achieving the LDL-C target. However, the recommendation to measure apoB levels—or LDL particles, lipoprotein(a), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein—was only made “based on individual patient clinical circumstances.” In 2021, a scientific statement from the National Lipid Association endorsed that the measurement of apoB is reasonable, not only as part of the initial lipid evaluation, but also in patients on lipid therapy.32 The document recognized that in high-risk patients with LDL-C level <70 mg/dL on lipid-lowering therapy, apoB measurement may effectively identify a patient with an increased ASCVD risk due to residual atherogenic lipoprotein burden who could benefit from additional therapy. Whereas various guidelines have recognized value in measuring apoB levels, there is considerably less agreement in apoB thresholds for risk or treatment.Guidelines consistently support that apoB level is a more accurate predictor of cardiovascular risk than triglyceride level, particularly in the presence of cholesterol-depleted apoB particles, and is recommended as the marker of choice for individuals with high triglyceride levels. However, no agreement exists on the specific triglyceride levels that define hypertriglyceridemia. Evidence also indicates that cholesterol-depleted apoB lipoproteins can occur outside of high triglyceride levels. In further exploring the link among triglycerides, apoB, and LDL-C, De Marco et al35 analyzed LDL-C:apoB ratios in a cohort of 6272 participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). They found that cholesterol-depleted apoB particles, as indicated by a low LDL-C:apoB ratio, can be present across all triglyceride levels, reporting that 21.4% of individuals with triglyceride levels <100 mg/dL exhibited a low LDL-C:apoB ratio.35 These findings reinforce the argument for the routine inclusion of apoB in clinical assessments for all patients, not just those with elevated triglyceride levels.Guideline Recommendations for ApoB Targets or Triggers

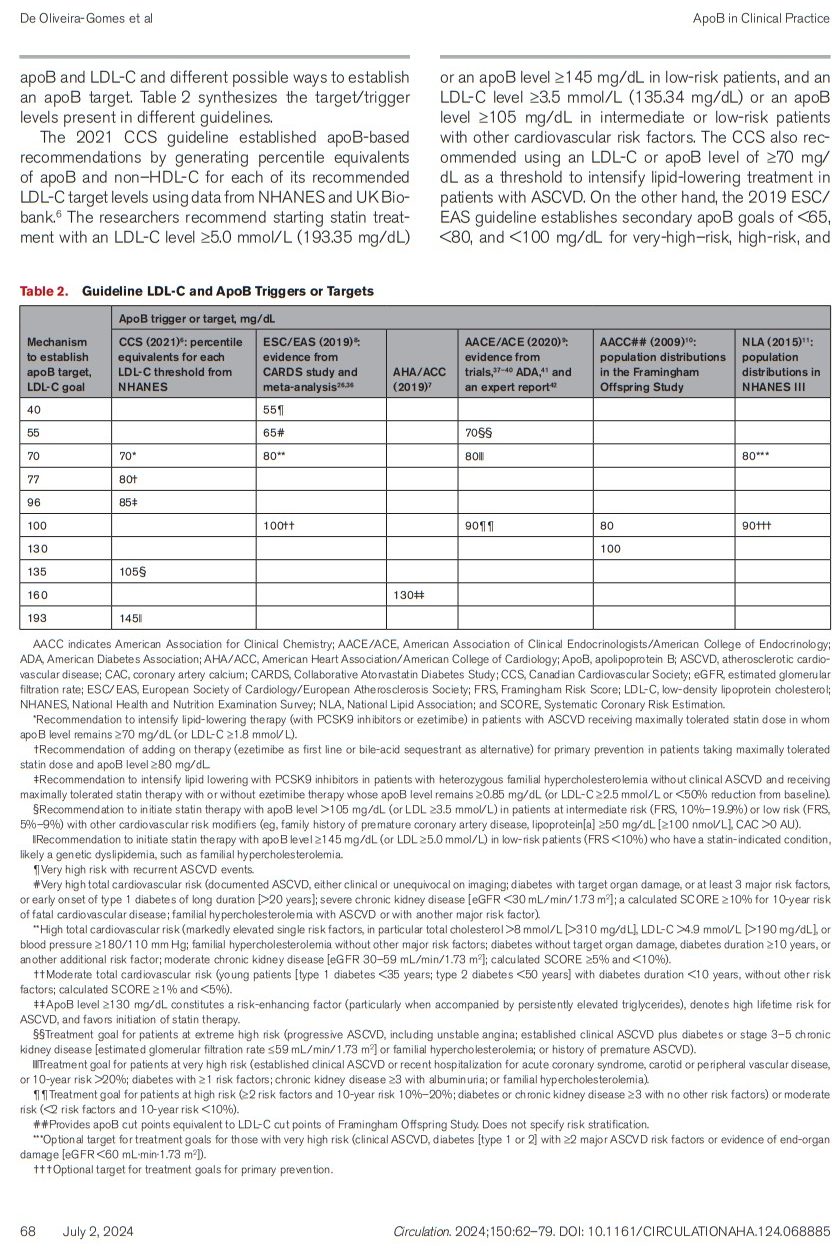

Guideline-based LDL-C targets vary considerably, partly on the basis of guideline publication year and temporal updates from iterative trial data, and partly because of differences among guidelines. However, even when the same LDL-C target is used (ie, <70 mg/dL), guidelines vary in the corresponding apoB level. This reflects the lack of a universally agreed upon conversion between apoB and LDL-C and different possible ways to establish an apoB target. Table 2 synthesizes the target/trigger levels present in different guidelines.The 2021 CCS guideline established apoB-based recommendations by generating percentile equivalents of apoB and non–HDL-C for each of its recommended LDL-C target levels using data from NHANES and UK Biobank.6 The researchers recommend starting statin treatment with an LDL-C level ≥5.0 mmol/L (193.35 mg/dL) or an apoB level ≥145 mg/dL in low-risk patients, and an LDL-C level ≥3.5 mmol/L (135.34 mg/dL) or an apoB level ≥105 mg/dL in intermediate or low-risk patients with other cardiovascular risk factors. The CCS also recommended using an LDL-C or apoB level of ≥70 mg/dL as a threshold to intensify lipid-lowering treatment in patients with ASCVD. On the other hand, the 2019 ESC/EAS guideline establishes secondary apoB goals of <65, <80, and <100 mg/dL for very-high–risk, high-risk, and moderate-risk patients, respectively, which corresponded to LDL-C targets of <55, <70, and <100 mg/dL.8In the United States, the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Multi-Society Cholesterol Guideline states that an apoB level ≥130 mg/dL corresponds to an LDL-C level ≥160 mg/dL and constitutes a risk-enhancing factor (particularly when accompanied by persistently elevated triglyceride levels) for which statin initiation or intensification can be considered.7 Meanwhile, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology suggests an apoB goal of <70, <80, or <90 mg/dL for individuals at extremely high risk (persistent ASCVD), very high risk (established ASCVD or diabetes plus ≥1 additional risk factor), or high or moderate risk (risk of ASCVD, including diabetes), respectively.9 In the 2015 National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia, the apoB recommendations are <80 mg/dL for high-risk patients and <90 mg/dL in primary prevention, both on the basis of NHANES III data.11 In 2009, an American Association for Clinical Chemistry working group established apoB cut points equivalent to LDL cut points on the basis of the Framingham Offspring Study.10 In this document, apoB levels of 80 and 100 mg/dL are considered equivalent to LDL-C levels of 100 and 130 mg/dL.POPULATION PERCENTILES OF APOB RELATIVE TO LDL-C

ApoB equivalents for LDL-C have been determined through various approaches using population percentiles. One method involves determining corresponding apoB values in individuals with a particular LDL-C level; the other involves aligning the LDL-C percentile corresponding to a particular LDL-C value and determining the same percentile value for apoB in that population. One challenge to this approach globally is that the population distribution of apoB in a population varies by region. Figure 3 shows the levels of apoB corresponding to the 10th, 50th, and 90th population percentiles based on studies from the United States, Canada, South Korea, India, Mexico, Finland, and Sweden.43–49 Not only do apoB levels vary in different populations, so do the levels of LDL-C and non–HDL-C.50,51 The CCS was the only guideline that established apoB triggers on the basis of LDL-C population percentile equivalents using data from NHANES and the UK Biobank.6 In contrast, in other guidelines, the equivalent apoB level suggested relative to LDL-C can be considerably higher in terms of population percentile.52 For example, the ESC/EAS, AACE/ACE, and National Lipid Association guidelines all use an apoB level of 80 mg/dL to correspond to an LDL-C level of 70 mg/dL. However, in NHANES and the Very Large Database of Lipids, an LDL-C level of 70 mg/dL corresponded to a population percentile–equivalent apoB value of 60 mg/dL (≈7th–9th percentile), whereas an apoB level of 80 mg/dL corresponded to a population percentile–equivalent LDL-C value of 100 mg/dL (≈31st–36th percentile).52Figure 3. Illustration of apolipoprotein B 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles in different countries. Data from the United States obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1991).43 Data from Canada obtained from a random sample of men and women age 18 to 74 years selected from Saskatchewan and Quebec (1989–1990).49 Data from South Korea obtained from patients residing in Seoul and Kyung-gee Do with an average age of 43.5±8.3 years.44 Data from India obtained from the health checkup program at Hinduja National Hospital.48 Data from Mexico obtained from the 1990 National Census.45 Data from Finland obtained from the population registers of the city of Turku and some adjacent rural and urban communities in southwestern Finland.47 Data from Sweden obtained from a Swedish population sample including individuals <20 to >80 years of age (1985–1996).46 apoB indicates apolipoprotein B.DISCORDANCE BETWEEN LDL AND APOB

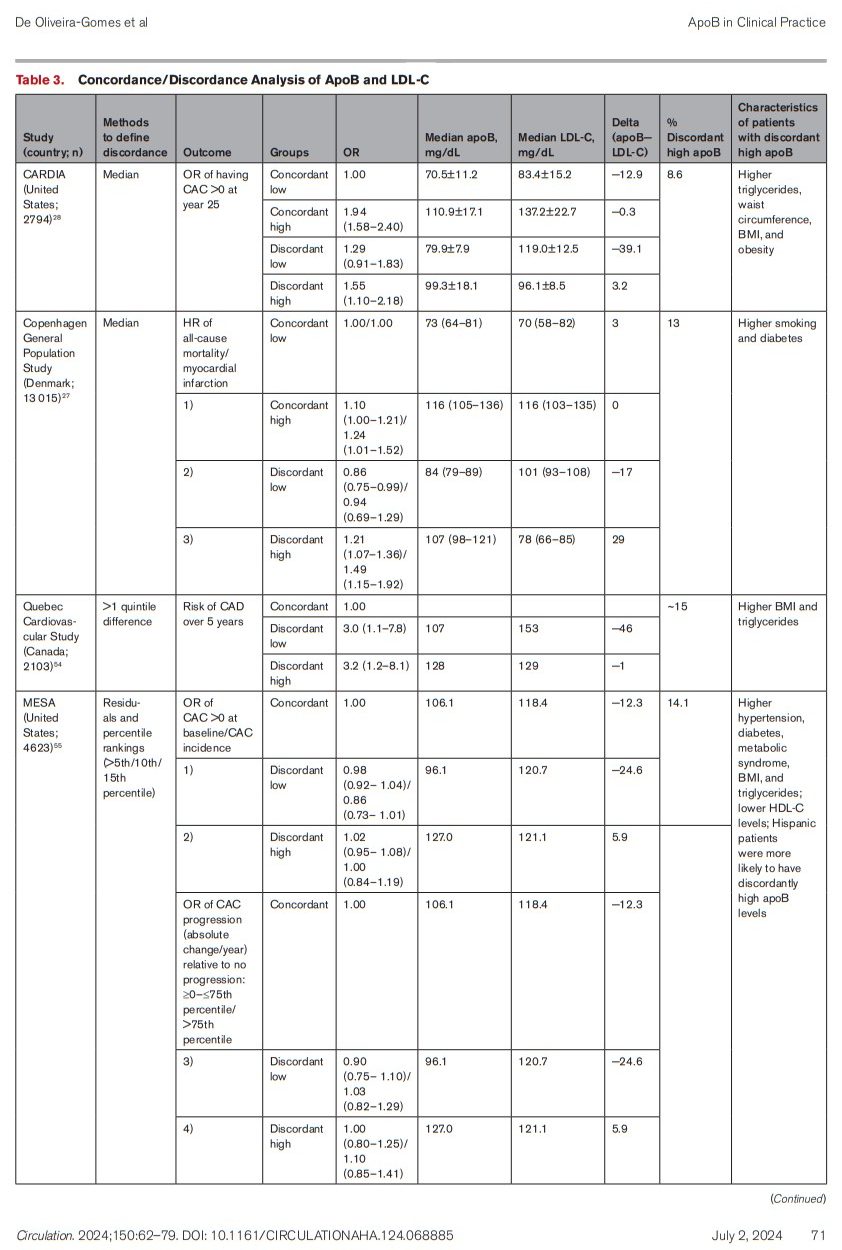

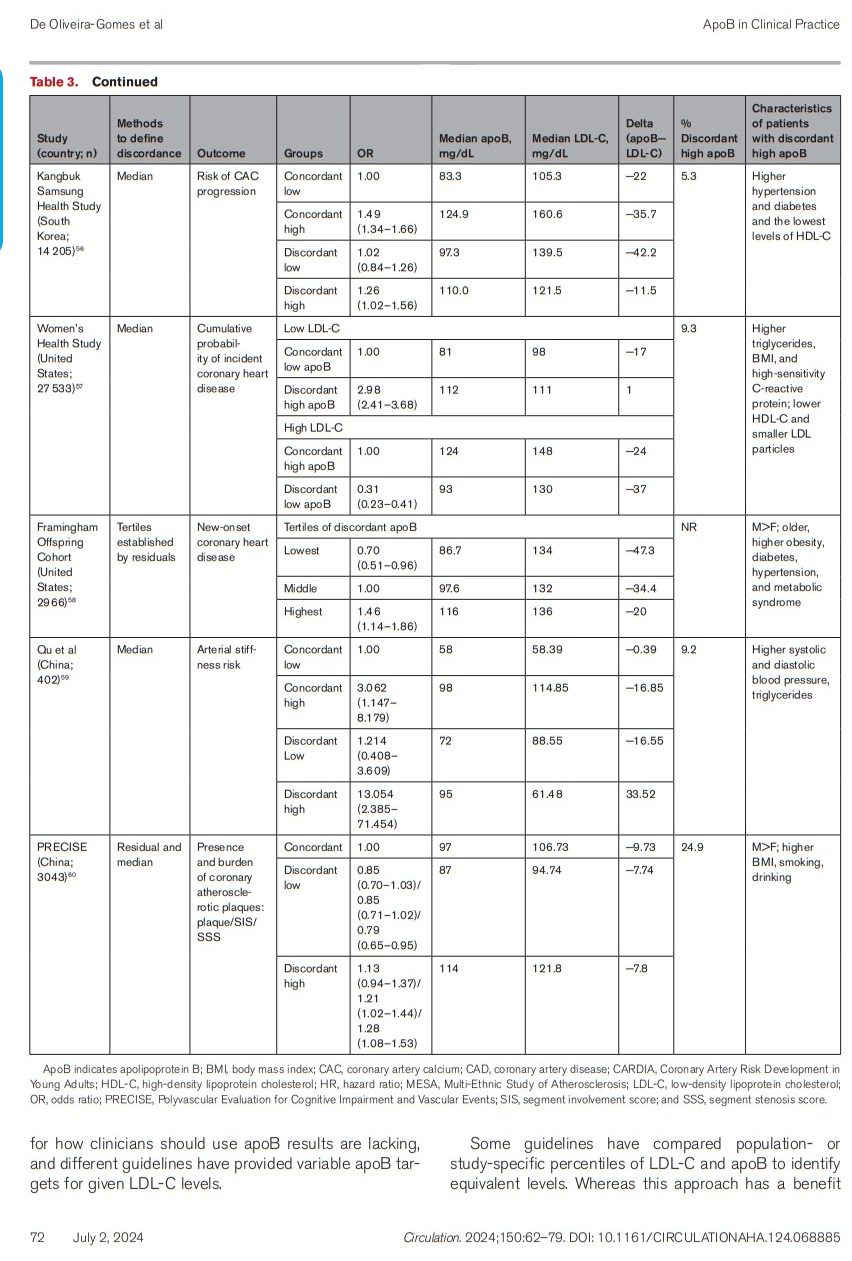

As mentioned previously, substantial variability exists in the amount of cholesterol carried by every lipoprotein; therefore, apoB, LDL-C, and non–HDL-C are not equivalent cardiovascular risk markers.53 For most patients, apoB and LDL-C levels are highly correlated, such that using LDL-C level accurately captures the majority of the patient’s atherogenic risk. Multiple “discordance analyses” have attempted to identify patients with discordant apoB and LDL-C levels and analyze their risk of cardiovascular events. Because there is no definitive ratio between LDL-C and apoB that defines a cholesterol-depleted versus cholesterol-enriched lipoprotein phenotype, most of the discordance studies have used median values of LDL-C and apoB to establish 4 different groups (ie, concordantly high or low apoB or discordantly high or low apoB in relation to LDL-C or non–HDL-C) to compare cardiovascular outcomes among them. Other studies have used various other methods. The manner of defining discordance, as well as the results of these discordance analyses, are summarized in Table 3.27,28,54–61Because of differences in the populations studied as well as the definition of discordance, the cutoffs used to identify adults with “discordantly high” and “discordantly low” apoB varied. Most of the studies used median values to define discordance; therefore, there was no specific difference between apoB and LDL-C levels to consider someone “discordantly high,” and the difference between apoB and LDL-C levels in these groups ranged from −11.5 to 33.52. The percentage of people with discordantly high apoB level ranged from 5.3% to 24.9%. Overall, men, smokers, and people with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, higher body mass index, higher triglyceride levels, or lower HDL levels were most likely to have discordantly high apoB relative to LDL-C, highlighting the need to test apoB levels in these populations because LDL-C data can be insufficient to fully capture ASCVD risk. [Emphasis added]APOB LEVELS ACHIEVED IN RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIALS

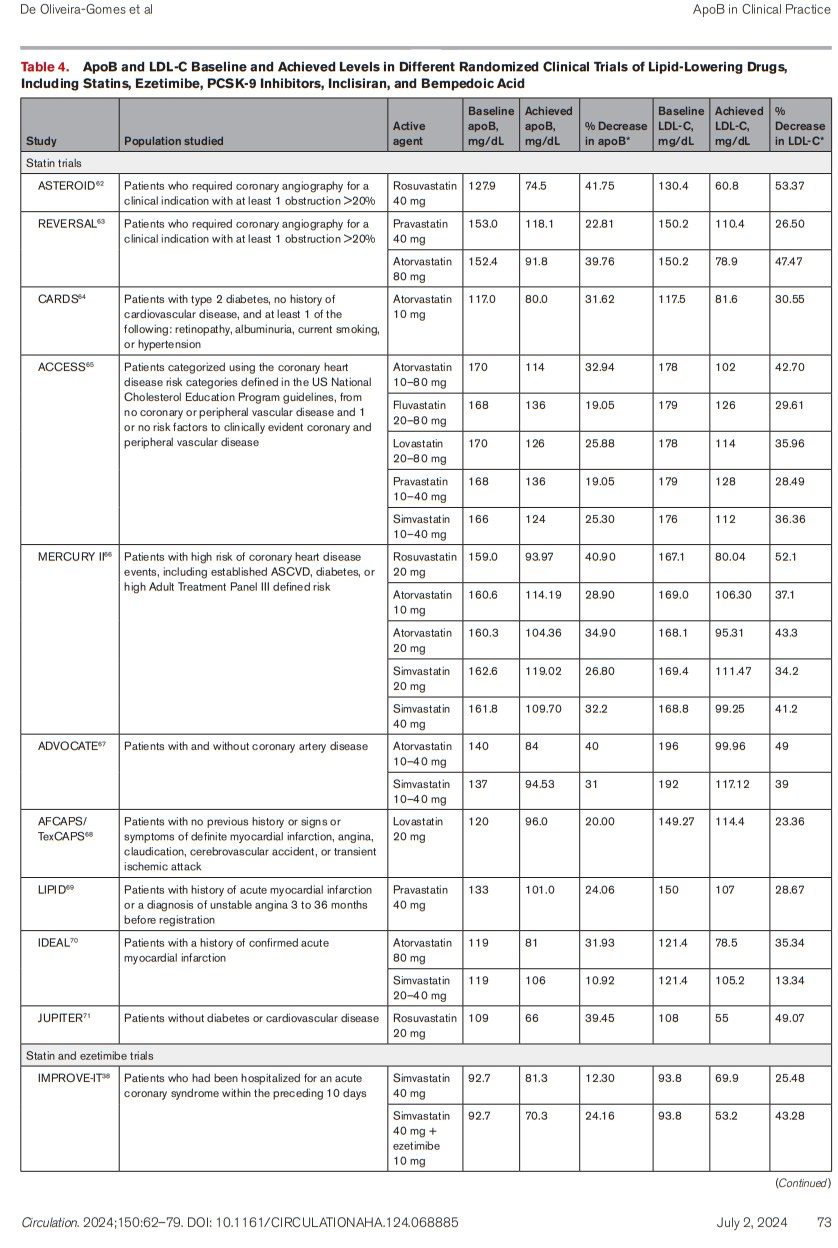

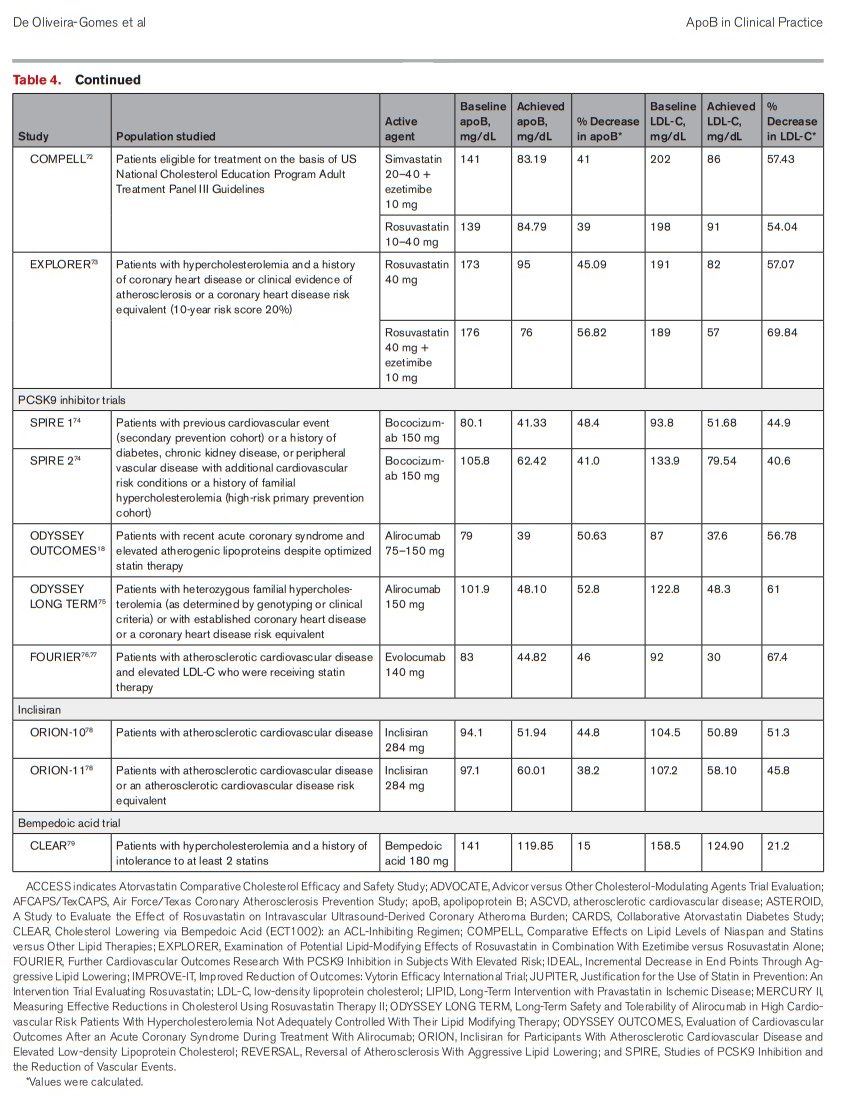

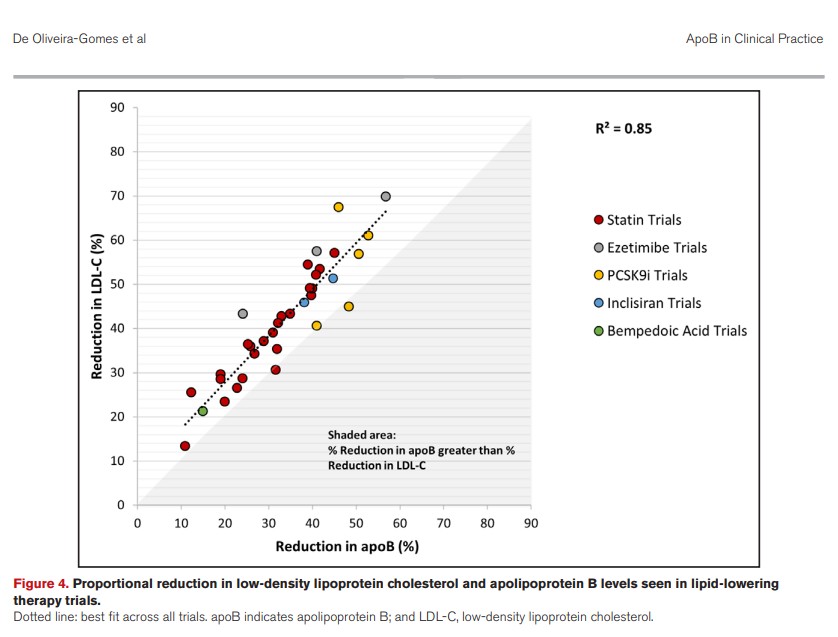

Whereas LDL-C level has been the main target for clinical trials of lipid-lowering therapy, many trials have also measured apoB levels both at baseline and on treatment. Data from trials that reported apoB level at baseline and achieved apoB levels are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4. Whereas the degree of LDL-C lowering varied across and within therapeutic classes, in statin, ezetimibe, PCSK9i, inclisiran, and bempedoic acid trials, the proportional reduction in LDL-C was greater than the proportional reduction in apoB. The degree of apoB reduction was highly correlated with the degree of LDL-C reduction, and the correlation between the percent reduction in apoB and the percent reduction in LDL-C across all other trials is high (R2=0.85). Overall, across all trials, the percent reduction of apoB was slightly lower than LDL-C. For statin, PCSK-9i, inclisiran, and bempedoic acid trials, the mean reduction in apoB was ~6% to 8% lower than the mean reduction in LDL-C; meanwhile, for the ezetimibe trials, the mean reduction in LDL-C was 16% higher than the apoB reduction. This difference could be explained by the mechanism of action of ezetimibe (ie, inhibiting cholesterol absorption from the small intestine) or attributable to differences in the populations enrolled in the trials.* Values were calculated.With respect to what the actual target apoB level should be, trial data can provide further evidence. Figure 5 shows the achieved LDL-C and apoB levels across statin, ezetimibe, PCSK9i, inclisiran, and bempedoic acid trials from Table 3. Across all trials, the on-treatment LDL-C and apoB levels attained are highly correlated (R2=0.85). For most trials of statins, ezetimibe, and inclisiran, on-treatment LDL-C levels were slightly lower than on-treatment apoB levels, whereas for PCSK9i and bempedoic acid, on-treatment LDL-C levels were slightly higher than on-treatment apoB levels. However, across all trials, the on-treatment LDL-C levels and on-treatment apoB levels were roughly equivalent.Figure 5. Achieved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and apolipoprotein B levels in lipid-lowering therapy trials. Dotted line: best fit across all trials. apoB indicates apolipoprotein B; and LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.Across clinical trials, the levels of apoB achieved in the treatment arms has varied on the basis of the population being studied and the type of treatment used, although trial data have consistently shown that with respect to apoB and LDL-C, lower is better. For instance, in statin trials, apoB levels ranged from 119 mg/dL in REVERSAL (Reversal of Atherosclerosis with Aggressive Lipid Lowering; pravastatin 40 mg) to 66 mg/dL in JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin; rosuvastatin 20 mg).63,71 When ezetimibe was combined with simvastatin in IMPROVE-IT, the apoB level reached 70 mg/dL.38 Contemporary outcomes trials of PSCK-9 inhibitor monoclonal antibodies achieved the lowest on-treatment apoB levels, averaging 39 mg/dL and 45 mg/dL in ODYSSEY and FOURIER, respectively.75–77 The latter 2 trials suggest a target apoB level in secondary prevention of at least <55 mg/dL, consistent with current European guideline recommendations.7SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND APOB TARGETS

The totality of data suggests that apoB may be a superior marker not only of risk of ASCVD but also of the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy compared with LDL-C. ApoB testing has practical benefits, including that patients do not need to fast, and is more accurate than LDL-C testing in patients with high triglyceride or very low LDL-C levels. Guidelines are increasingly recommending more aggressive lipid reduction; therefore, obtaining precise lipid measurements is essential. This has led many to call for the preferential use of apoB over LDL-C testing. However, consistent recommendations for how clinicians should use apoB results are lacking, and different guidelines have provided variable apoB targets for given LDL-C levels.Some guidelines have compared population- or study-specific percentiles of LDL-C and apoB to identify equivalent levels. Whereas this approach has a benefit of potentially identifying similar numbers of individuals for treatment, variability across populations in the distribution of LDL-C and apoB could lead to continued variability in global guidelines for optimal apoB targets. Discordance analyses have confirmed that people with metabolic syndrome or hypertriglyceridemia are at highest risk of discordantly high apoB levels and reinforce current guideline recommendations to measure apoB in these populations. However, variability across analyses in how discordance was defined limits their use in guiding clinical management. Nevertheless, all discordance analyses demonstrated that regardless of LDL-C levels, those with elevated apoB levels are at increased risk of ASCVD, reinforcing the importance of measurement of apoB.Percentage Reductions in ApoB

Given this, trial data appear to be most useful in developing clinical recommendations for how to implement apoB data to guide treatment recommendations. In terms of proportional reduction, all the lipid-lowering therapy included appeared to reduce apoB levels slightly less than LDL-C levels. Thus, if targeting a ≥50% LDL-C reduction (as recommended by many guidelines) with statins, ezetimibe, PSCK-9i, inclisiran, or bempedoic acid, a comparable apoB reduction would be 40% to 45%.ApoB Treatment Targets

To guide treatment targets, the trial data provide a straightforward path. Because the on-treatment LDL-C levels and on-treatment apoB levels were nearly identical, the same number can be used for apoB as LDL-C. Thus, if a target LDL-C level is <70 mg/dL, the target apoB level should also be <70 mg/dL (0.70 g/L). In high-risk patients with a target of LDL-C level <55 mg/dL, the corresponding goal for apoB should be <55 mg/dL (0.55 g/L). This simple approach can be communicated easily to patients and treating physicians and could eliminate confusion between guidelines.CONCLUSIONS

ApoB testing offers a standardized, accurate, and cost-effective measurement of the total number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles in plasma, providing a more accurate assessment of ASCVD risk and effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapy. Unlike LDL-C testing, apoB testing is particularly advantageous in patients with discordant lipid profiles, such as those with high triglyceride levels, or in patients with insulin resistance, who are more likely to have cholesterol-depleted apoB particles. ApoB testing is also more accurate when the levels of LDL-C are lower, a common situation in clinical practice when guidelines suggest more aggressive treatment targets. Despite this, apoB testing faces barriers to widespread adoption in clinical practice, primarily due to the absence of consistent guidance on its interpretation and application. To address these challenges and on the basis of evidence in RCTs, this review suggests the use of the same number for LDL-C as for apoB when establishing treatment targets. Simplification of the interpretation of apoB values, by aligning apoB targets with LDL-C levels, could enhance its integration into routine practice. The use of apoB levels in clinical decision-making holds promise for more accurate ASCVD risk prediction and tailored lipid-lowering strategies.