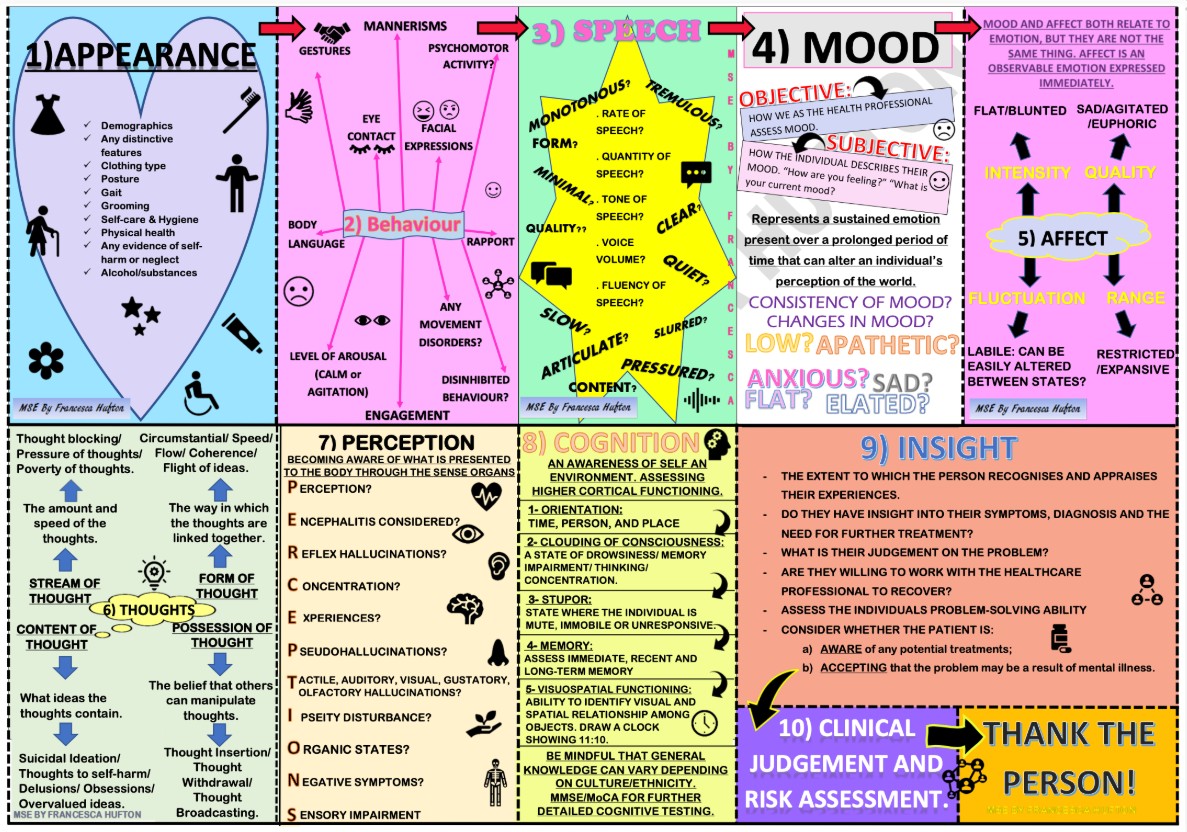

In addition to today’s resource, please see and review 10 Point Guide To Mental State Examination (MSE) In Psychiatry: (Click on the image below to enlarge the image)

Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from The Alzheimer’s Association clinical practice guideline for the diagnostic evaluation, testing, counseling, and disclosure of suspected Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (DETeCD-ADRD): Validated clinical assessment instruments. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Alzheimers Dement. 2025 Jan;21(1):e14335. doi: 10.1002/alz.14335. Epub 2024 Dec 23.

All that follows is from the above resource.

- Abstract

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. CONCLUSIONS

- AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

- CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

- Supporting information

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Contributor Information

- DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

- REFERENCES

- Associated Data

Abstract

US clinical practice guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) or AD and related dementias (ADRD) are decades old and aimed at specialists. This evidence-based guideline was developed to empower all-including primary care-clinicians to implement a structured approach for evaluating a patient with symptoms that may represent clinical AD/ADRD. As part of the modified Delphi approach and guideline development process (7374 publications were reviewed; 133 met inclusion criteria) an expert workgroup developed recommendations as steps in a patient-centered evaluation process. The workgroup provided a summary of validated instruments to measure symptoms in daily life (including cognition, mood and behavior, and daily function) and to test for signs of cognitive impairment in the office. This article distills this information to provide a resource to support clinicians in the implementation of this approach in clinical practice. The companion articles provide context for primary care and specialty clinicians with regard to how to fit these instruments into the workflow and actions to take when integration of performance on these instruments with clinical profile and clinician judgment support potential cognitive impairment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease; Lewy body dementia; cerebrospinal fluid; dementia; diagnosis; frontotemporal dementia; magnetic resonance imaging; mild cognitive impairment; molecular biomarkers; positron emission tomography; vascular cognitive impairment.

© 2024 The Author(s). Alzheimer’s & Dementia published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Alzheimer’s Association.

TABLE 1.

Validated instruments to assist in the structured reporting of symptoms of cognitive impairment.

Instrument Purpose Features Comments IQCODE 29 , 30 , 31 The first informant‐based questionnaire to rate change in cognitive function from the person’s previous ability. Original had 26 items; short version has 16 questions that measure cognitive decline from premorbid level. Each item is rated on a 5‐point scale from 1 (“much better”) to 5 (“much worse”) and ratings are averaged, with 3 representing no change. Validated in people with dementia against other measures of cognitive decline. Not influenced by education, pre‐morbid ability, or language proficiency, but is affected by informant characteristics and the quality of the relationship between the informant and the subject. Less sensitive to MCI. Available at https://nceph.anu.edu.au/research/tools‐resources/informant‐questionnaire‐cognitive‐decline‐elderly Information from the IQCODE and the MMSE can be combined in the DemeGraph (https://biostats.com.au/Demegraph/) to aid in assessing for dementia.

AD8 32 Brief screening (2–3 minutes) interview that can differentiate between individuals with and without cognitive impairment. A patient or informant rates yes/no questions about memory, orientation, judgment, and everyday function. The AD8 is a valid and reliable dementia screening measure compared to the expert clinical judgment and neuropsychological assessments. The AD8 is an appropriate screening tool for dementia but may not be sensitive to other more acute or subtle forms of cognitive dysfunction. Available at https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/ad8‐dementia‐screening.pdf QDRS 33 10 item questionnaire completed by informant, rating change from premorbid baseline on an ordinal scale from 0 to 3, which when summed aim to capture the types and severity of cognitive and behavioral symptoms and impact on daily function. The QDRS is a free screening and staging tool (not a diagnostic tool). It can be used as a structured screen for cognitive, behavioral, and functional changes and symptoms as well as for staging severity. QDRS scores correlate with the longer CDR (see Table 3). Takes 7‐10 min of informant time. Score range interpretations: normal 0‐1; MCI 2‐5; mild dementia 6‐12; moderate dementia 12‐20; severe dementia 21‐30. Available at https://umiamibrainhealth.org/downloads/the-quick-dementia-rating-system-qdrs-patient-and-informant-versions/ AQ 34 , 35 Developed as primary care tool to detect cognitive impairment due to AD. The AQ is an informant‐based assessment consisting of 21 yes/no questions that can be administered in ≈ 3 minutes. The individual items are divided into the domains of memory, orientation, functional ability, visuospatial, and language. Items that receive a “yes” response are given 1 point; six items particularly associated with clinical AD more weighted and are given 2 points. The total AQ score ranges from 0 to 27; normal ≤4; MCI 5–14; AD dementia ≥15. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3207359/pdf/nihms325035.pdf

ECog 36 , 37 Assesses functional abilities that are linked to specific cognitive abilities. 39‐item questionnaire can be given to informants and separately to patients. Scoring produces one global factor and six domain‐specific factors. Subsequent studies support validity of short‐form ECog‐12 in discriminating against people with dementia from cognitively normal individuals, but less sensitivity for MCI. Validated against other measures of functional and neuropsychological impairment. The original ECog and ECog‐12 are detailed in Farias et al. 36 and Tomaszewski Farias et al. 37 CFI 38 The CFI was developed to facilitate evaluation of cognitive symptoms in dementia prevention studies. 14‐item questionnaire focused on change in cognitive and functional abilities over the previous year, which is completed by patient or separately by informant. Total scores range from 0 to 14 (yes = 1, no = 0, and maybe = 0.5), with higher scores indicating greater subjective cognitive complaints. In people with MCI, informant rating is useful for prognosis. 39 Full questionnaires are available in Li et al. 39 Cognitive Change Index 40 Originally developed from measures to detect subjective cognitive decline A 20‐item questionnaire asking patients and informants to separately rate change in cognitive function compared to the previous 5 years on a scale of 1 (no change) to 5 (severe change). Questions cover memory, executive function, and language. Validation study showed that scores from informant reports are abnormally elevated in people with MCI or dementia. Available from the authors upon request. Cambridge Behavioural Inventory 41 , 42 , 43 Developed to assist in the differential diagnosis of different forms of dementia. A 45‐item informant‐completed questionnaire that obtains information about a range of cognitive, mood and behavioral, and daily functional symptoms. May be best for specialty settings or some general practice settings. Available at https://www.sydney.edu.au/brain-mind/resources-for-clinicians/dementia-test.html SIST‐M 44 , 45 Developed as an interview (≈ 25 minutes) for history of symptoms of cognitive and functional impairment SIST‐M has high reliability against the CDR score in people with MCI and mild dementia. An informant‐rated questionnaire has also been developed. Best for specialty settings. Available in Okereke et al. 44 , 45 Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AD8, Eight‐item Information nterview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia; AQ, Alzheimer’s Questionnaire; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; ECog, Everyday Cognition; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; QRDS, Quick Dementia Rating Scale; SIST‐M, Structured Interview and Scoring Tool–Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

TABLE 2.

Validated instruments to assist in the assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD/ADRD.

Name Format Considerations General instruments for neuropsychiatric symptoms NPI‐Q 51 12‐item questionnaire completed by informant; each item is first rated as “present/absent” (Yes/No); if present, severity is rated on 3‐point scale from mild (1) to severe (3). Severity total range: 0–36 (none‐max) Symptom Distress (how much it affects informant/care partner): rated on 6‐point scale (0–5). Distress range: 0–60 (none‐max)

Covers broad range of symptoms/behaviors. It is a modified (abbreviated) version of the NPI. The 12 neuropsychiatric domains assessed are: delusions; hallucinations; agitation/aggression; depression/dysphoria; anxiety; elation/euphoria; apathy/indifference; disinhibition; irritability/lability; motor disturbance (e.g., pacing, picking, repetitive motor behaviors); night‐time behaviors; and appetite/eating. Suitable for both detection and tracking progression/monitoring.

Provides information regarding severity of symptoms (how noticeable it is in the patient) and the amount of distress it is causing the care partner/informant. Some modified versions (e.g., NACC UDS) only gauge symptom severity.

It can take 5 to 10 minutes depending on proficiency of administrator and familiarity of informant and whether both severity and distress are elicited.

A total score can also be derived by multiplying severity score and distress score for each item and summing across all items. Available at:

NPI 52 12 items administered in a structured interview to informant with ratings similar to those above (NPI‐Q) Requires training and proficiency to administer. Used widely in clinical research and more suitable administration to specialist setting; NPI‐Q provides good proxy in clinical setting. Available at:

BEHAVE‐AD 53 , 54 25 item scale administered to informant; presence of symptoms and impact on patient for each item rated from 0 to 4 (not present to severe) Global impact severity on care partner/informant is rated for each item from 0 to 4 (not troubling to severely troubling)

Covers broad range of symptoms/behaviors. Mostly used in clinical research setting and more suited to specialist setting; ≈ 20 to 25 minutes to administer; solicits presence of behavioral symptoms and their impact. Suitable for detection, staging, and tracking progression/monitoring.

MBI‐C 17 34‐item questionnaire structured to be consistent with the five domains in the MBI criteria: decreased motivation, emotional dysregulation, impulse dyscontrol, social inappropriateness, and abnormal perception or thought content. If a question is endorsed as present, it is rated mild, moderate, or severe. Questionnaire to be used primarily by family members or other close informants to systematically measure behavioral changes exhibited by older adults that might precede the onset of dementia. It was specifically designed to: (1) operationalize the MBI concept; (2) measure a selected list of neuropsychiatric symptoms which may help identify prodromal illness; and (3) help predict risk of dementia due to AD or ADRD. The primary goal is case detection of a behavioral pre‐dementia state not better captured by other diagnostic criteria. Depression instruments GDS 55 15 items Patient self‐administered (but can be administered to patient)

Yes/No responses

Quick (3–5 minutes) screening tool for depressive symptoms and depression in older adults, public domain. Scores of 5–8 suggest potential for mild depression; 9–11 moderate depression; 12–15 severe depression.

Suitable for detection (and abbreviated monitoring) in MCI and mild dementia. Less suitable for more advanced and severe dementia and individuals with poor comprehension; and for monitoring severe depression.

PHQ‐9 56 9 items Patient self‐administered (clinician verified)

Each item rated 0–3: 0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day

Range 0–27 (no depression–severe depression)

Quick (3–5 minutes) screening, diagnostic, and monitoring tool for depressive symptoms and depression in older adults widely use in primary care. Has been validated in individuals with MCI/dementia Scores of 5–9 suggest mild depression; 10–14 moderate depression; > 14 moderately severe/severe depression. Also available in shorter 4‐ and 2‐item versions.

Suitable for detection and monitoring in MCI and mild dementia. Less suitable for more advanced and severe dementia and individuals with poor comprehension. Available download from: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/1725/phq9-patient-health-questionnaire9

CSDD 19 items Administered to patients and care partner (patient does not need to be able to answer for scale to be completed.

Each item rated: 0 = absent; 1 = mild to intermittent; 2 = severe

Scores range from 0 to 38 (none–max depressive symptoms)

Well suited for detecting, tracking progression, monitoring depression, and depressive symptoms across severity spectrum of MCI‐dementia. Scores of > 11 suggestion probable depression.

Anxiety Instruments PSWQ‐A 57 8 items Patient self‐administered (can also be administered to care partner/informant)

Ratings for each item are on a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = not at all typical of me; 5 = very typical of me)

Range 8–40 (no anxiety–severe anxiety)

A widely used abbreviated version of the 16‐item PSWQ that was developed as a screening tool to assess worry symptoms and anxiety in older adults. It is in the public domain.

Cut‐off of 17 has been suggested for detection of significant anxiety in individuals with mild/moderate dementia. 58

GAI 59 20 items Patient self‐administered (can also be administered to care partner/informant)

All items answered dichotomously Yes (1) or No (0)

Range: 0–20 (none–max severity)

Was developed to screen for anxiety symptoms in older/geriatric population, has been subsequently studied in mild to moderate AD dementia (a cut off score of 8 has been suggested to detect significant in mild/moderate dementia 58 ). Suitable for detection of symptoms. It is copyrighted and fee may be required for clinical use.

A short form with five items (GAI‐SF) is also available for very brief screening.

Agitation instruments CMAI Presence and frequency of 29 behaviors Does not rate severity

Administered to care partner informant.

Broadly covers presence of agitation and related disruptive behaviors such as verbal aggression, repetitiveness, screaming, hitting, grabbing, and sexual advances. Requires training to administer, more suited to specialist setting and clinical research. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease related dementias; BEHAVE‐AD, Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Depression Scale; CMAI, Cohen Mansfield Agitation Index; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; GAI, Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MBI‐C, Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPI‐Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory‐Questionnaire; PHQ‐9, Patient Health Questionnaire; PSWQ‐A, Penn State Worry Questionnaire Abbreviated.

TABLE 3.

Validated instruments to assist in the structured assessment of functional impairment in instrumental and basic ADL in patients with cognitive impairment.

Instrument Purpose IADL BADL Features Comments FAQ 71 IADLs of older adults in the community with and without cognitive impairment or mild dementia Yes No 10 items rated on a 4‐point scale ranging from: ‘’dependent (3), requires some assistance (2), has difficulty but does by self (1), performs task normally (0)‘’ also category for “not applicable (N/A) or never did” Useful for initial assessment of IADLs in suspected MCI or mild dementia. Not useful for longitudinal tracking of changes beyond mild to moderate dementia stages. Available at https://www.alz.org/careplanning/downloads/functional‐activities‐questionnaire.pdf CDR 77 , 78 , 79 Geared primarily toward typical AD dementia, the CDR was developed to provide a global clinician‐rated measure of the presence and severity of cognitive symptoms and their functional impact. Yes Yes Structured interview and examination approach for the trained (usually specialist) clinician to integrate information from history and brief examination to grade the types and severity of impairment in three domains of cognitive abilities (memory, orientation, and judgment) and in three domains of daily function (community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). Global rating indicates very mild (0.5), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) dementia. The CDR Sum of Boxes measure ranges from 0 (cognitively unimpaired) to 18 (severe global impairment). The CDR is well established as a reliable and valid combined cognitive and functional assessment measure for patients with MCI and dementia due to AD and has been used with patients with ADRD as well. It is widely used as a clinical trial outcome measure and a clinical research staging instrument. It is relatively time consuming and therefore used in a limited fashion in specialty clinical practice settings. FAST 80 , 81 , 82 Based on the previously developed Global Deterioration Scale for typical AD dementia, 83 the FAST characterizes a patient’s daily function through 16 ordinal stages ranging from cognitively unimpaired to severe dementia. Yes Yes The FAST has been validated in primary and specialty care settings and can be administered by clinical or non‐clinical staff. The FAST is administered by interviewing a care partner or the patient if at a mild level of impairment. The description that best fits the person’s performance is the stage in which the person is functioning. In typical AD dementia, symptoms progress in sequence. However, atypical dementias may not follow this sequence.

Widely used in geriatric medicine and in the US Veterans Administration Health Care System. Often used as a measure by which to determine preliminary eligibility for palliative or hospice care in patients with severe dementia. Bristol Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (BALDS) 84 Basic and instrumental ADLs in individuals with dementia in most settings Yes Yes 20 items Range of 0–60 (independent–dependent)

Items rated on a 4‐point scale (0,1,2,3).

Useful for initial assessment and tracking of IADLs and BADLs across the spectrum of dementia stages. DAD 85 Leisure activities, IADLs, ADLs in individuals with dementia of the AD type. Yes Yes 40 items (23 IADL items; 17 BADL items) Range of 0%–100% (dependent‐independent)

Items rated on a 2‐point scale (0,1) or N/A; Yes, did activity without reminder or assistance = 1; No did not do activity or needed reminder or assistance for activity = 0;

Scores added for all questions not rated N/A and converted to % score

Useful for initial assessment and for tracking of leisure activities, IADLs, and BADLs across the spectrum of dementia stages. DAD‐6 86 A modified version of the DAD scale focusing on executive components of six instrumental items to detect early impairment in a non‐demented population. Yes No 18 items in six categories Range of 0–18 (dependent–independent)

Items rated on a 2‐point scale (0,1) or N/A; Yes, did activity without reminder or assistance = 1; No did not do activity or needed reminder or assistance for activity = 0;

Categories: meals; travel; use of telephone/computer; finances and correspondence; drug intake; leisure and household care

Less studied but may be useful for initial assessment of leisure activities and IADLs in suspected MCI. For each category there is a question regarding initiation, organizing and planning, and effective implementation. Not useful beyond mild dementia stages. Lawton and Brody IADL scale 87 Instrumental activities of older adults in the community with and without cognitive impairment or dementia. Yes No eight items Range of 0–8 (dependent–independent) for women (and traditionally 0–5 for men)

Women are scored on all eight areas of function; historically, for men, the areas of food preparation, housekeeping, laundry have been excluded. Individuals are scored according to their highest level of functioning in each category.

Long history of use. Limited assessment of psychometric properties. May be useful for initial assessment of MCI and dementia. Available at https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/lawton‐brody‐activities‐daily‐living‐scale.pdf A‐IADL‐SV 75 Short version of A‐IADL for leisure activities and IADLs in MCI/mild dementia. Yes No 30 items from seven categories. Computer scored against normative distribution

Computerized administration. Psychometric properties of A‐IADL well studied. Available to professionals for clinical and non‐profit use with registration at: https://www.alzheimercentrum.nl/professionals/amsterdam‐iadl/ Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADL, activities of daily living; ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease related disorders; A‐IADL‐SV, Amsterdam IADL‐short version; BADL, basic activities of daily living; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia Scale; DAD‐6, six‐item version of the DAD scale; FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; FAST, Functional Assessment Staging Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

TABLE 4.

Validated mental status test instruments.

Name Time (minutes) Considerations MoCA 13 10–15 Widely available in multiple versions and languages, well suited for detection of MCI; tracks progression through mild to moderate dementia. Interpret with caution in individuals with low education. Range 0–30 (max performance). MoCA domain index scores (e.g., MIS) are easily calculated and helpful to delineate pattern of performance on cognitive domains. MoCA is freely available. Training/certification at mocatest.org MoCA variants adapted for telemedicine available (see Box 1)

MMSE 109 , 110 7–10 Widely known and well studied; more suited for detection of dementia; lower sensitivity for detection of MCI and tracks progression through severe dementia. Range 0–30 (max performance). Proprietary—not free for clinical use.

MMSE‐like variants have been adapted for telemedicine (see Box 1)

Mini‐Cog 111 2–4 Combines three‐time word list learning and recall with clock drawing test; provides rapid screen—more suitable for detection of dementia than MCI. Is available as part of Alzheimer’s Association Cognitive Assessment Toolkit along with GPCOG, Clock Drawing Test, and Memory Impairment Screen at: https://www.alz.org/media/documents/cognitive‐assessment‐toolkit.pdf

GPCOG 112 Patient 2–5 informant 1–3 Widely used outside United States in general practitioner setting; more suited for detection of dementia; lower sensitivity MCI detection. Includes a clock drawing test with range of 0–2. Range of 0–9 on patient exam. Informant component (when complaint is informant‐based or score on patient exam is < 9) has a range of 0–4. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/cognitive‐assessment‐toolkit.pdf

SLUMS 113 7–10 Developed and mostly used in VA population; suited to detection of MCI and dementia; tracks progression through moderate stages dementia. Range 0–30 (max performance). Available at: http://aging.slu.edu/pdfsurveys/mentalstatus.pdf M‐ACE 114 5–8 A short version of items from the ACE‐III (see below) that includes temporal orientation (0–4 points); learning of a name and address (0–7 points) with delayed recall (0–7 points) after distractor tasks of animal naming in 60 s (0–7 points) and a clock drawing test (0–5 points); range 0–30 (max performance). Better sensitivity for dementia than MMSE at all cut‐offs due to less ceiling effect. Blessed OMC Test (OMCT, BOMC), aka Short Blessed Test (SBT; 6‐Item Cognitive Impairment Test 6‐CIT) 115 5–7 Short version of BDS‐IMC; more suited to detection of amnestic dementia; verbal only (no writing/drawing); heavily weighted toward memory and information; does not assess visuospatial and executive functions and can be administered via telemedicine. Requires weighting of scores. Range from 0 to 28 (original version counted errors—28 was max for errors). Available at: http://regionstrauma.org/blogs/sbt.pdf and page 3 of:

https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn4/BHL/docs/Vol_5_Clinician_Resources.pdf

MIS 116 4–5 A four‐item delayed free‐ and cued‐recall test of memory; uses controlled learning to assess remembering of four written items; range 0–8 (2 x items freely recalled + items with cued recall). Available at: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/memory‐impairment‐screening‐mis.pdf AMTS 117 3‐5 A 10‐item scale that assesses orientation, registration and recall, and concentration. Does not assess visuospatial function. Scores of 6 or below, from a maximum score of 10, suggest potential dementia level performance. May not have high sensitivity for detection of MCI, particularly non‐amnestic MCI. BIMS 118 2–3 Cognitive screener used in nursing homes as part of Minimal Data Set 3.0. Consists of repetition of three words, temporal orientation to month, year and day; and recall of three words. BIMS scores range from 0 to 15 (cognitively intact 13–15; moderate impairment 8–12; severe impairment 0–7). Available at: Clock Drawing Test 119 1–2 Quick screen of aspects of visuospatial cognition, conceptualization, and executive function (planning/organization); qualitative assessment can inform regarding errors in conceptual design (including meaning of a clock), stimulus boundedness, perseveration, visual spatial relations, planning, and graphomotoric function. Several variations and scoring systems possible—with max scores often ranging from 3 to 10 (on MoCA performance range is 0–3); avoid using in isolation. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/cognitive‐assessment‐toolkit.pdf

T&C 120 2–4 Two tasks to determine “dementia” level impairment: tell the time presented on a clock face, and make $1 when provided by 3 quarters, 7 dimes, and 7 nickels; avoid using in isolation 7MS 121 7–12 Developed and suited for detection of AD/dementia; components test memory (enhanced free and cued recall), temporal orientation, semantic (animal category) verbal fluency and a 7‐point clock drawing test, administration and scoring may be better suited for specialty setting STMS 122 10–15 Robust test for assessing several domains to detect and track MCI and dementia; validated in primary care, administration and scoring may be better suited for specialty setting. More sensitive than MMSE to distinguish normal cognition from prevalent MCI; superior to MMSE in detecting subtle cognitive performance deficits in individuals with normal cognition who later developed incident MCI or AD dementia. Score range 0–37 (max performance). Available at: https://www.ouhsc.edu/age/Brief_Cog_Screen/documents/STMS.pdf

Blessed Dementia Scale Information‐Memory‐Concentration Test (BDS‐IMC; BIMC) 123 10–15 Well‐validated for AD neuropathology and detecting and tracking AD dementia progression from mild through very severe stages. May not have high sensitivity to detect non‐amnestic MCI. Verbal tests (no writing/copying) with emphasis on memory and information (limited executive function and no visuospatial component) and can be administered via telemedicine. Score range 0–37 errors (37 is max errors; higher score denotes worse performance) CAMCOG 124 20–25 Suited for specialty settings; provides cognitive domain scores through eight major subscales (orientation, language, memory, attention, praxis, calculation, abstract thinking, perception); is part of CAMDEX interview; score range 0–106 (max performance) ACE‐III 125 20–30 Suited for specialty settings; provides multiple cognitive domains including specific scores for attention, memory, fluency, language, and visuospatial; useful for delineating cognitive‐behavioral syndrome and differential diagnosis. Score range 0–100 (max performance) FAB 126 10 Suited for specialty settings; provides a structured examination of frontal systems function by assessing conceptualization, mental flexibility, motor programing, sensitivity to interference, inhibitory control, and environmental autonomy. Score range 0–18 (max performance) Abbreviations: 7MS, 7‐minute screen; ACE, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Exam; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AMTS, Abbreviated Mental Test Score; BIMS, Brief Interview for Mental Status; CAMCOG, Cambridge Cognitive Examination; CAMDEX, Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; GPCOG, General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; M‐ACE, Mini Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Exam; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MIS, Memory Index Score; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SLUMS, St. Louis University Mental Status; STMS, Short Test of Mental Status; T&C, Time and Change Test; VA, Veterans Administration.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of selected brief cognitive tests to detect cognitive impairment or dementia.

Name MoCA MMSE Mini‐Cog SLUMS M‐ACE GPCOG Time to administer (minutes) 10–15 7–10 2—4 7–10 6–9 2–5 patients 1–3 informant

Cutoff for potential cognitive impairment < 26/30 (1 point added to raw score if ≤12 years of education

< 26/30 ≤ 3/5 < 27/30 for ≥12 years of education

< 25/30 for

≤12 years of education

Two suggested: < 26/30 has 92% positive predictive value (PPV); < 22 has 100% PPV for dementia (62% sensitivity, 100% specificity)

< 5 patient Or

< 8 patient and

< 4 informants

Sensitivity for cognitive impairment 90% 81% 76% 96% 80%–85% 85% Specificity for cognitive impairment 87% 82% 89% 61% 85%–87% 86% Cognitive domains assessed Complex attention ✓ ✓ ✓ Executive function ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Learning and memory ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Language ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Visual construction ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Orientation ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Available in multiple languages? Yes No Yes No No Yes Other considerations ● Index scores can be calculated to better inform domain‐specific performance ● Mixed findings in people with low education

● Well‐known among clinicians ● Purchase required

● Limited evidence for sensitivity to detect mild changes

● Simple scoring algorithm ● Limited evidence for sensitivity to detect mild changes

● Evidence for sensitivity to detect mild changes ● Largely studied in veteran populations

● Provides broad range for learning and memory performance (14 points) ● Limited direct assessment of language—only verbal fluency for semantic animal category tested

● Validated in primary care settings ● Limited evidence for sensitivity to detect mild changes

Abbreviations: GPCOG, General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; M‐ACE, Mini Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Exam; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SLUMS, St. Louis University Mental Status.

BOX 1: Pragmatic Adoption of the DETeCD‐ADRD CPG in the Context of Remote Assessment of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

Telemedicine has been emerging over the past decade for a variety of purposes, particularly to enable better access to medical specialty services. With the pandemic of 2020, the field exploded. Many of the core elements and recommendations of this clinical practice guideline can be adapted pragmatically for telemedicine. Core elements 1‐4 and 7 are readily adaptable to telemedicine formats as they involve patient‐centered discussions of processes and goals; interview‐based history taking, review of systems, questionnaires and assessments; and communication of findings and development of a shared plan of care (Recommendations 1‐5, 10‐11). There is also evidence to support that cognitive‐behavioral examination including administration of brief mental status test instruments can also be pragmatically adapted to the telemedicine format 141 and so can neuropsychological evaluation by a skilled neuropsychologist (Recommendation 14). 142 Some elements of the physical and neurologic examination that require the direct laying on of hands are not possible in a remote format (e.g., elements of Core 5 and Recommendations 6, 13) and the vast majority of Tier 1‐4 laboratory tests and studies (Recommendations 8‐9; 15‐19) would require a visit to a laboratory, imaging facility, or other medical facility. Nevertheless, we believe it is possible to adapt much of the material in these guidelines to telemedicine, enabling the detection of impaired Cognitive Functional Status and the characterization of the Cognitive‐Behavioral Syndrome. By accomplishing these goals, it may be possible in many patients to begin to develop the differential diagnosis of potential etiology(‐ies) and guide next steps in evaluation, disclosure and care.

The instruments in Tables 1‐5 are readily adaptable to telemedicine to assist in characterization of cognitive symptoms, neuropsychiatric symptoms, behaviors and mood, functional impairment in activities of daily living, and staging of dementia. Home‐based telemedicine assessment of key domains of cognition, daily function and behavior in individuals older than 75 years of age is feasible and can detect and track cognitive impairments 142 ; these have included assessment of cognitive performance with brief validated mental status instruments designed for telephone administration such as the TICS (Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status), 143 as well as neuropsychological tests of memory, attention/concentration, executive functions and processing speed. 142 , 144 Different variants of the TICS have been validated for telephone administration and cut‐off scores and correspondence to MMSE scores have been reported. 145

Several of the standardized mental status test instruments that have been adapted to telemedicine do not have motoric or visuospatial components and only require verbal responses (e.g. SBT, BDS‐IMC) thus facilitating their easy administration by telephone or video. Other common instruments have variants that have been adapted for telephone or video administration, including the MoCA and variants of the MMSE.

Various options exist for telemedicine administration of the MoCA (see https://www.mocatest.org/remote‐moca‐testing/), with the caveat that they require further validation for specific cut‐offs and potential age‐ and education‐adjustments. These include the “Telephone MoCA” which, similarly to the MoCA‐Blind/Visually Impaired (MoCA‐B), 146 does not administer the first 4 items of the full MoCA (mini Trails‐B; 3‐D figure copy; clock test, naming of 3 animal drawings) that have a visual or motoric component, and that account for 8 points; hence the MoCA‐B has a range of 0‐22. An approximate cut off score of 18 (that converts proportionally to a score of 25.5 on the 30‐point MoCA, which is approximately 26 and the cut‐off of possible impairment) has been suggested as possibility indicating cognitive impairment, but this requires further validation. Directions for adaptation and administration of a full MoCA‐variant via audio‐videoconference (thus ranging from 0‐30), that includes adapted administration of the first 4 items, can also be found at https://www.mocatest.org/remote‐moca‐testing/. For example, adaptions include for the mini Trails B to be presented to the patient on video and to ask the patient to “please tell me where the arrow should go to next with respect to the pattern I am showing you?”; and for orientation to place and city, to ask the patient “where is the clinic/institution I am calling you from?” and “what is the city in which our clinic/institution is located?”. For such MoCA‐variants, preliminary evidence supports acceptable test‐retest and inter‐rater reliability and patient satisfaction of in‐person versus audiovideo administration. 147 , 148 Variations of MMSE‐like tests have also been studied and validated for telephone administration, and include 22‐point (e.g. ALFI‐MMSE, 149 MMSET 150 ) and 26‐point variants (TMMSE 151 ); these often omit or adapt questions such as following a 3‐step command, reading and repeating a sentence, reading and obeying a command, writing a sentence, and copying intersecting figures, and may shorten the naming task to one item (instead of two), by asking the patient to “name the thing you are speaking into as you talk to me” (the telephone).

While best clinical practice guidelines for tele‐neuropsychological assessments will need to be developed, there is already a substantial evidence‐base to support the reliability and validity of neuropsychological evaluation of patients by experienced professionals utilizing tele‐neuropsychological (especially via video conference) assessment. 142 , 144 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 The administration of verbally‐mediated tasks using existing norms is supported, and pragmatic use of visually dependent tasks can be adapted. 144 Gaps to address include development of standardized methods for the presentation of visual stimuli, and development and incorporation of complex tasks often used to assess processing speed, complex attention, and those that rely on motor and visual abilities. 144

A strong and growing evidence base demonstrates that telemedicine does not impede, and in many ways can facilitate successful clinical, cognitive and neuropsychological evaluation of patients with cognitive impairments. While older individuals and those with cognitive impairments can have unique challenges with remote testing, including access and use of video technology, yet these can be surmountable with dedicated effort and resources. The principal benefits of telemedicine can include improved access to care, patient satisfaction, convenience, a lower burden on working family members/informants to participate, mitigation of exposure risks for vulnerable individuals, and potential cost savings. 142 , 144 , 155 We will undoubtedly see further guidance on methods for remote cognitive assessment and further evidence regarding validity against in‐person administration, as well as practical utility

2. CONCLUSIONS

The cornerstone of the diagnostic assessment of a patient with symptoms concerning AD or ADRD is the history and examination. Although advances in molecular biomarkers of brain diseases leading to cognitive impairment will likely enable their detection in some patients at an asymptomatic stage, the ability of proficient clinicians to recognize and diagnose patients in the early symptomatic stages of these illnesses is critical to optimize early management and hopefully minimize the adverse impact of these diseases on daily function and safety. Although it is common for a history to be taken and an examination to be performed without the use of specific validated instruments, evidence indicates and the DETeCD‐ADRD workgroup strongly believes that the use of such instruments will lead to better outcomes. Instruments to assess symptoms in daily life and their impact on function can be given to patients and informants prior to an office visit and can serve as a mechanism for structuring the history and efficiently identifying areas for focused clinical interviewing while also providing a list of pertinent negatives. A brief neurologic exam tailored to the patient is also important, as is a mental status exam augmented with a validated cognitive assessment instrument. The score on the test should not be interpreted in isolation, but should be integrated with information from the HPI, the patient’s demographic background and psychosocial history, family history and other information relevant to the risk profile, medical history, medications, and other relevant information. For proficient clinicians, the synthesis of this information should lead to a diagnostic formulation of the patient’s cognitive functional status and cognitive‐behavioral syndrome. In some cases, neuropsychological assessment or additional consultation(s) may be required to develop or further refine these first two steps of the diagnostic formulation.

If a patient has MCI or dementia, an evaluation should be done to determine the likely etiology, if possible, as discussed extensively in the companion articles. 19 , 156 These diagnostic elements set prior probabilities on the differential diagnosis of likely etiology (‐ies), which informs clinical decision making regarding Tier 1 to 4 tests and other assessments in the evaluation process. See the primary care companion article for discussion of structural neuroimaging and cognitive lab panel blood tests. 19 In some cases, the steps in this process may be relatively straightforward, and in others they may be quite complex. See the specialty care companion article for discussion of specialized functional and molecular neuroimaging and for fluid molecular biomarkers. 156 Ultimately, the evaluation process should lead to a diagnostic formulation that is communicated clearly and compassionately to the patient and care partner, along with a discussion of management and prognosis.

.