Today, I review, link to and excerpt from the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Oct 4;80(14):1366-1418. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006. Epub 2022 Aug 25. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]

All that follows is from the above resource.

Preface

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) has a long history of developing documents (eg, decision pathways, health policy statements, appropriate use criteria) to provide members with guidance on both clinical and nonclinical topics relevant to cardiovascular care. In most circumstances, these documents have been created to complement clinical practice guidelines and to inform clinicians about areas where evidence is new and evolving or where sufficient data is more limited. Despite this, numerous gaps persist, highlighting the need for more streamlined and efficient processes to implement best practices in patient care.

Central to the ACC’s strategic plan is the generation of actionable knowledge—a concept that places emphasis on making clinical information easier to consume, share, integrate, and update. To this end, the ACC has shifted from developing isolated documents to creating integrated “solution sets.” These are groups of closely related activities, policy, mobile applications, decision-support tools, and other resources necessary to transform care and/or improve heart health. Solution sets address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care. They use both established and emerging methods to disseminate information for cardiovascular conditions and their related management. The success of solution sets rests firmly on their ability to have a measurable impact on the delivery of care. Because solution sets reflect current evidence and ongoing gaps in care, the associated tools will be refined over time to match changing evidence and member needs.

Expert Consensus Decision Pathways (ECDPs) represent a key component of solution sets. Standard methodology for developing an ECDP is as follows: for a high-value topic that has been selected by the Science and Quality Committee and prioritized by the Solution Set Oversight Committee, a group of clinical experts is assembled to develop content that addresses key questions facing our members.1 This content is used to inform the development of various tools that accelerate real-time use of clinical policy at the point of care. ECDPs are not intended to provide single correct answers to clinical questions; rather, they encourage clinicians to consider a range of important factors as they define treatment plans for their patients. Whenever appropriate, ECDPs seek to provide unified articulation of clinical practice guidelines, appropriate use criteria, and other related ACC clinical policy. In some cases, covered topics will be addressed in subsequent clinical practice guidelines as the evidence base evolves. In other cases, these will serve as stand-alone policy.

Nicole M. Bhave, MD, FACC

Chair, ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee

Table 1. Criteria for Defining Patients at Very High Risk∗ of Future ASCVD Events

Major ASCVD Events Recent ACS (within the past 12 months) History of MI (other than recent ACS event listed above) History of ischemic stroke Symptomatic PAD (history of claudication with ABI <0.85 or previous revascularization or amputation)

High-Risk Conditions Age ≥65 years Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia History of prior coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention outside of the major ASCVD event(s) Diabetes Hypertension CKD (eGFR 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) Current smoking Persistently elevated LDL-C (LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL [≥2.6 mmol/L]) despite maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe History of congestive HF ABI = ankle-brachial index; ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF = heart failure; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI = myocardial infarction; PAD = peripheral artery disease

- ∗

Very high risk includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions.

Reprinted with permission from Grundy et al.7

- Consistent with expert guidance provided in the 2017 ACC nonstatin ECDP, 6 the 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guideline recommends use of an LDL-C threshold of ≥70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) to consider the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients with ASCVD.7

- Ezetimibe is recommended as the initial nonstatin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD who are receiving maximally tolerated statin therapy and have an LDL-C level ≥70 mg/dL.7

- In patients with clinical ASCVD who are judged to be at very high risk and are being considered for PCSK9 mAb therapy, maximally tolerated LDL-C–lowering therapy should include maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe.7

- The 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guideline includes the following value statement: “At mid-2018 list prices, PCSK9 mAbs have a low cost value (>$150,000 per quality-adjusted life year [QALY]) compared with good cost value (<$50,000 per QALY).”7

- In patients with primary severe hypercholesterolemia LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, recommendations are provided for the addition of ezetimibe, PCSK9 mAbs, or bile acid sequestrants (BAS) (see Section 5.2).7

- In primary prevention patients at borderline or intermediate risk of ASCVD by the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE), the clinician-patient risk discussion should include risk-enhancing factors that may confer a higher risk state and may support a decision to initiate or intensify statin therapy (see Table 2). Risk-enhancing factors are useful for further personalizing the initial risk estimate based on patient-specific factors that are not considered in the PCE and may carry greater lifetime risk. Several risk-enhancing factors may also be specific targets of therapy beyond the risk factors in the PCE.7

In primary prevention patients at borderline or intermediate risk of ASCVD by the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE), the clinician-patient risk discussion should include risk-enhancing factors that may confer a higher risk state and may support a decision to initiate or intensify statin therapy (see Table 2). Risk-enhancing factors are useful for further personalizing the initial risk estimate based on patient-specific factors that are not considered in the PCE and may carry greater lifetime risk. Several risk-enhancing factors may also be specific targets of therapy beyond the risk factors in the PCE.7

Table 2. Risk-Enhancing Factors for Clinician–Patient Risk Discussion

Risk-Enhancing Factors

- Family history of premature ASCVD (men aged <55 years; women aged <65 years)

- Primary hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C 160-189 mg/dL [4.1-4.8 mmol/L); non–HDL-C 190-219 mg/dL [4.9-5.6 mmol/L]∗

- Metabolic syndrome (increased waist circumference, elevated triglycerides [≥150 mg/dL], elevated blood pressure, elevated glucose, and low HDL-C [<40 mg/dL in men; <50 mg/dL in women] are factors; tally of 3 makes the diagnosis

- Chronic kidney disease (eGFR 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 with or without albuminuria; not treated with dialysis or kidney transplantation)

- Chronic inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis, RA, or HIV/AIDS

- History of premature menopause (before age 40 years) and history of pregnancy-associated conditions that increase later ASCVD risk, such as preeclampsia

- High-risk races/ethnicities (eg, South-Asian ancestry)

- Lipids/biomarkers: Associated with increased ASCVD risk

- Persistently∗ elevated, primary hypertriglyceridemia (≥175 mg/dL)

- If measured:

- 1. Elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (≥2.0 mg/L)

- 2. Elevated Lp(a): A relative indication for its measurement is family history of premature ASCVD. An Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dL or ≥125 nmol/L constitutes a risk-enhancing factor, especially at higher levels of Lp(a).

- 3. Elevated apoB ≥130 mg/dL: A relative indication for its measurement would be triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL. A level ≥130 mg/dL corresponds to LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL and constitutes a risk-enhancing factor

- 4. ABI <0.9

ABI = ankle-brachial index; AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; apoB = apolipoprotein B; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a) = lipoprotein (a); RA = rheumatoid arthritis.

- ∗ Optimally, 3 determinations.

Reprinted with permission from Grundy et al.7

▪ In adults without diabetes and with LDL-C levels ≥70 to 189 mg/dL at a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% to <20%, if the decision about statin therapy is uncertain, it is recommended to consider measuring coronary artery calcification.7

- If the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score is 0 AU, it is reasonable to withhold statin therapy and reassess in 5 to 10 years, as long as higher-risk conditions are absent (diabetes, family history of premature coronary heart disease, cigarette smoking);

- If the CAC score is 1 to 99 AU and less than the 75th percentile for the age/sex/race group, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy for patients ≥55 years of age;

- If the CAC score is 100 AU or higher or in the 75th percentile or higher for the age/sex/race group, it is reasonable to initiate statin therapy.

The 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guideline recommendations significantly refine personalization of risk assessment in primary prevention, more accurately characterize the risk of recurrent ASCVD events in secondary prevention, and carefully guide clinicians in matching the intensity of LDL-C–lowering therapies, both statin and nonstatin therapies, to the patient’s level of risk.

Since publication of the 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guideline, 3 additional nonstatin therapies—bempedoic acid, evinacumab, and inclisiran—have received FDA approval for management of hypercholesterolemia. While awaiting ongoing cardiovascular outcomes trials and subsequent revision of evidence-based guidelines, the ACC recognized that clinicians, patients, and payers may seek more specific recommendations on when to use newer nonstatin therapies if the response to statin therapy, ezetimibe, and/or PCSK9 mAbs is deemed inadequate.

2.2. Process

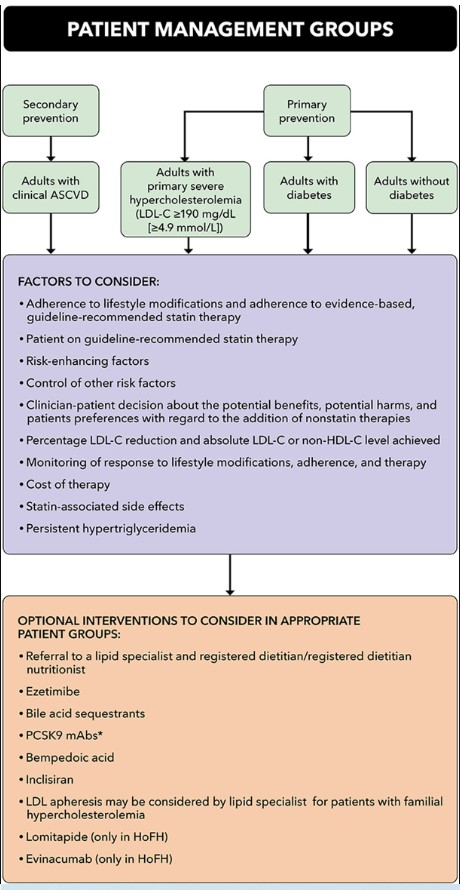

The writing committee began its deliberations by endorsing the construct of the 4 patient management groups identified by the 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guideline (see Figure 1).2 The writing committee then considered the potential for net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit of the use or addition of nonstatin therapies in each of the 4 groups. Within each of these groups, higher-risk subgroups were considered separately, given the potential for differences in the approach to combination therapy in each of these unique groups.

Figure 1. Summary Graphic: Patient Populations Addressed and Factors and Interventions to Consider

∗PCSK9 mAb includes alirocumab and evolocumab.

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HoFH = homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9 mAb = proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 monoclonal antibodies.

Lifestyle intervention: In agreement with the 2013 ACC/AHA and 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety cholesterol guidelines, for all patient groups, the current consensus emphasizes that lifestyle modifications (ie, adherence to a heart-healthy diet, regular exercise habits, avoidance of tobacco products, and maintenance of a healthy weight) remain critical components of ASCVD risk reduction, both before and in concert with the use of cholesterol-lowering drug therapies. . . . As this ECDP specifically addresses considerations for the incorporation of nonstatin therapies in selected high-risk patient populations, it is critical that the clinician assess and reinforce adherence to intensive lifestyle changes before the initiation of these additional agents. The reader is referred to the 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association and the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines for comprehensive recommendations.29,30