Today I link to and excerpt from European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis – Endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Eur Stroke J. 2017 Sep;2(3):195-221. doi: 10.1177/2396987317719364. Epub 2017 Jul 21.

The above resource has been cited by 57 articles in PubMed.

There are 117 similar articles in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

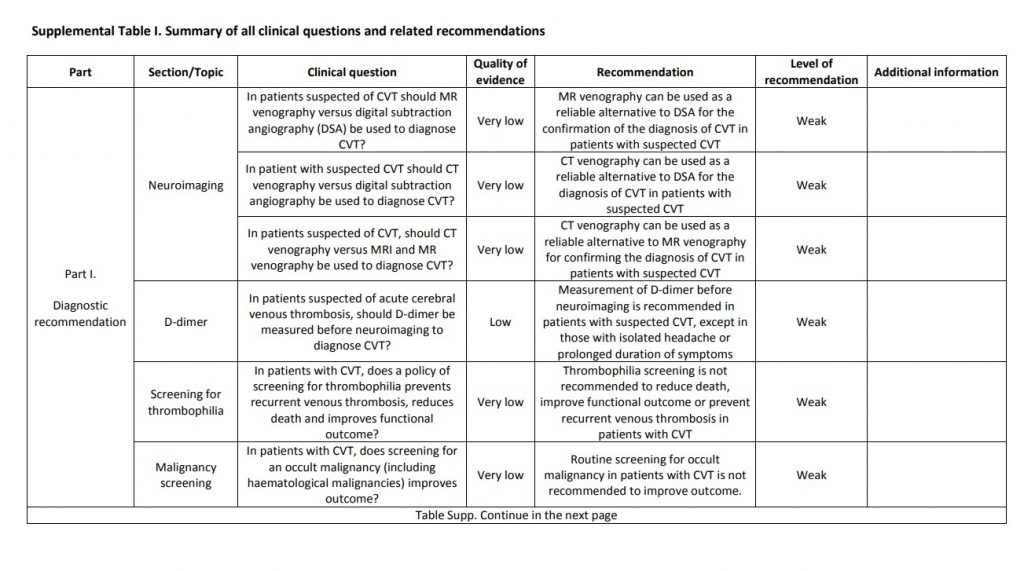

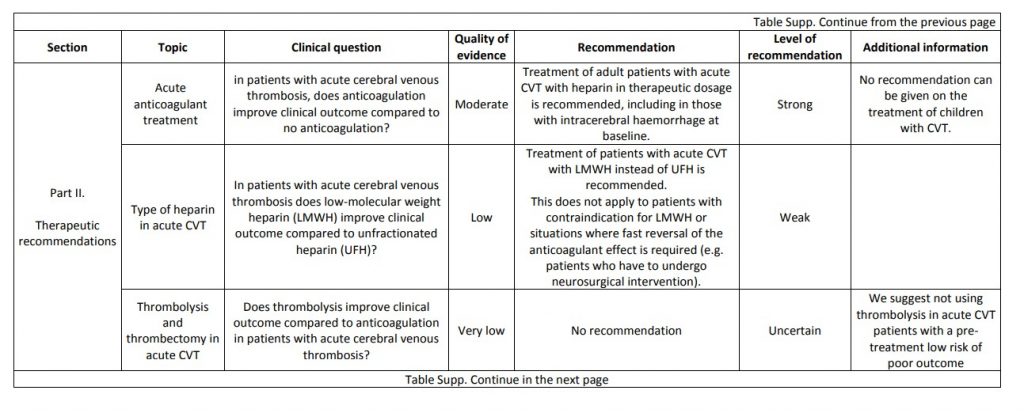

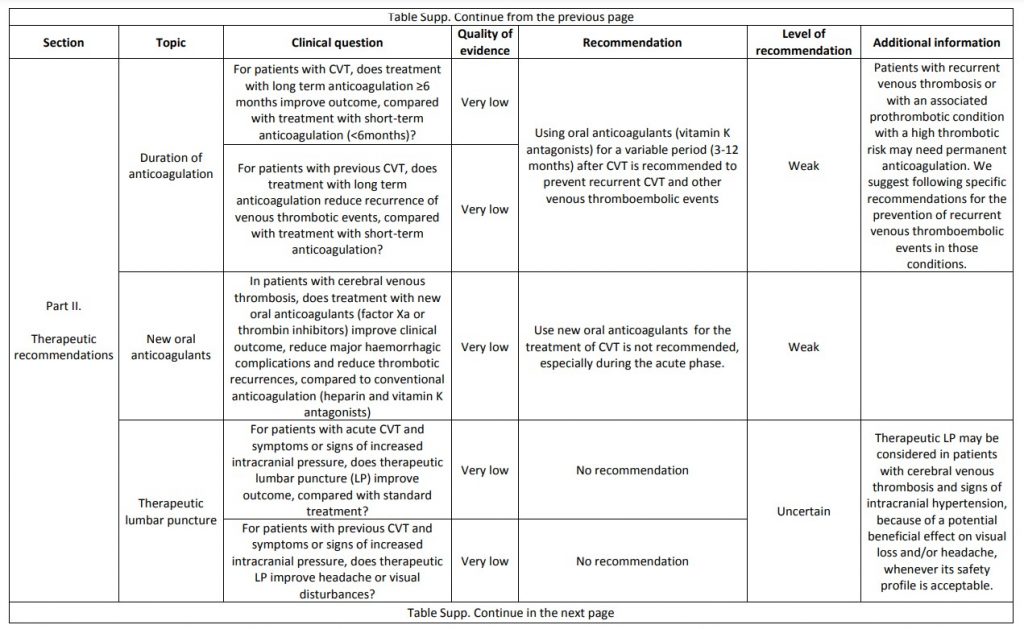

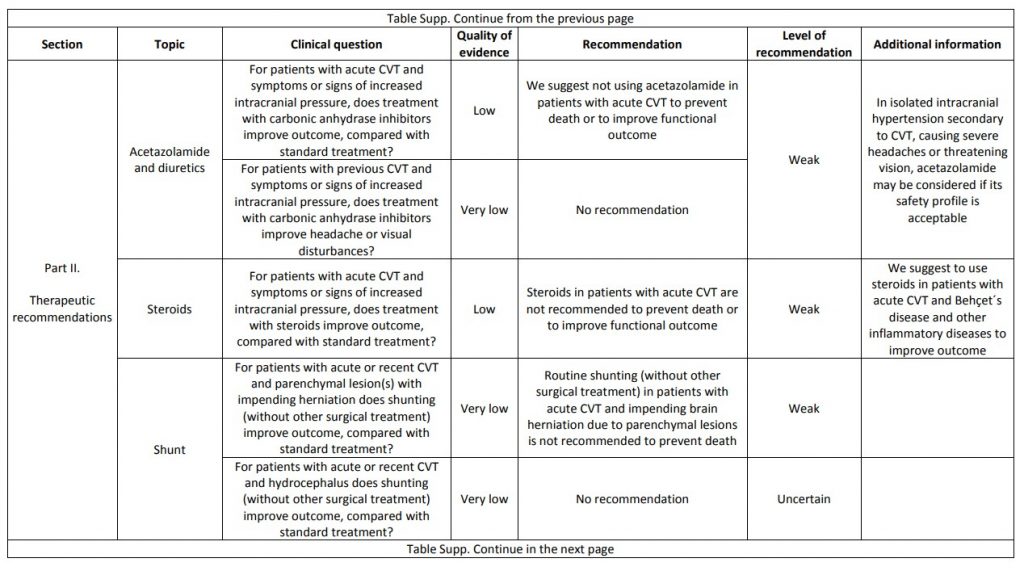

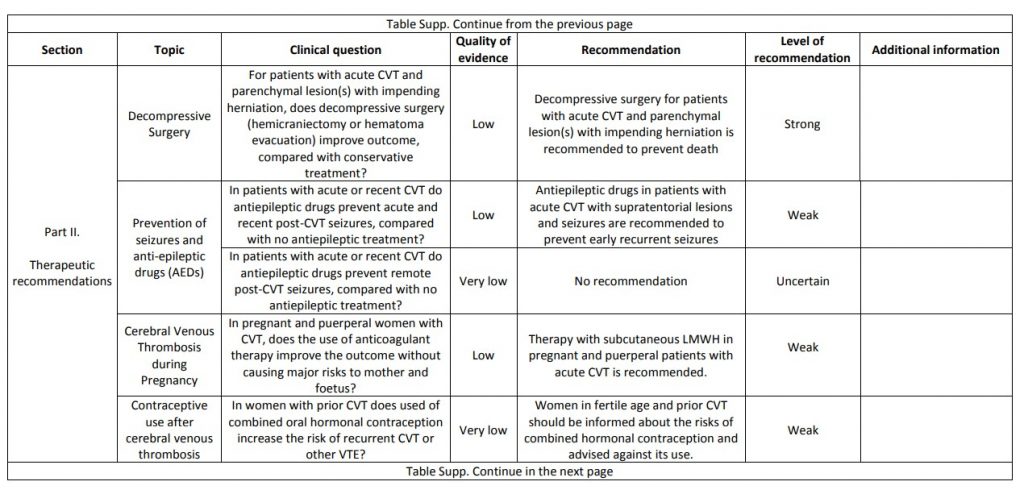

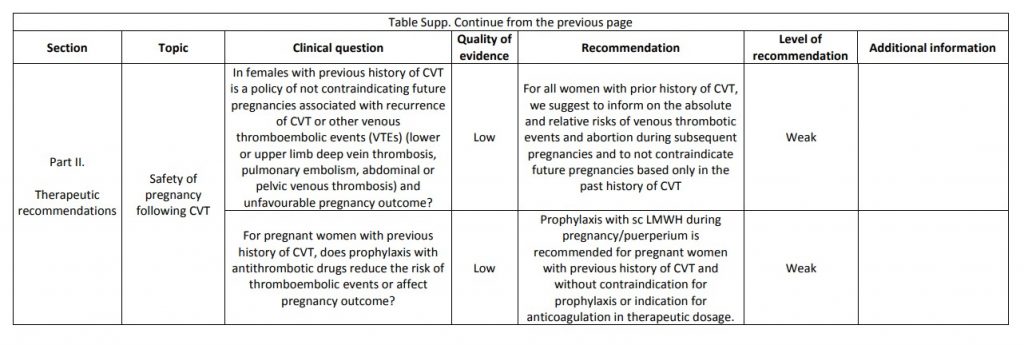

The current proposal for cerebral venous thrombosis guideline followed the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system, formulating relevant diagnostic and treatment questions, performing systematic reviews of all available evidence and writing recommendations and deciding on their strength on an explicit and transparent manner, based on the quality of available scientific evidence. The guideline addresses both diagnostic and therapeutic topics. We suggest using magnetic resonance or computed tomography angiography for confirming the diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis and not screening patients with cerebral venous thrombosis routinely for thrombophilia or cancer. We recommend parenteral anticoagulation in acute cerebral venous thrombosis and decompressive surgery to prevent death due to brain herniation. We suggest to use preferentially low-molecular weight heparin in the acute phase and not using direct oral anticoagulants. We suggest not using steroids and acetazolamide to reduce death or dependency. We suggest using antiepileptics in patients with an early seizure and supratentorial lesions to prevent further early seizures. We could not make recommendations due to very poor quality of evidence concerning duration of anticoagulation after the acute phase, thrombolysis and/or thrombectomy, therapeutic lumbar puncture, and prevention of remote seizures with antiepileptic drugs. We suggest that in women who suffered a previous cerebral venous thrombosis, contraceptives containing oestrogens should be avoided. We suggest that subsequent pregnancies are safe, but use of prophylactic low-molecular weight heparin should be considered throughout pregnancy and puerperium. Multicentre observational and experimental studies are needed to increase the level of evidence supporting recommendations on the diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis.

Background

CVT is a type of stroke where the thrombosis occurs in the venous side of the brain circulation, leading to occlusion of one or more cerebral veins and dural venous sinus. The incidence of CVT is estimated nowadays to be 1.32/100,000/year in Western Europe.4 The incidence is higher in developing countries. CVT is more frequent in women. The age distribution of CVT is different from that of ischemic stroke, CVT being more frequent in children and young adults.CVT has a variable clinical presentation ranging from mild cases presenting only headache, headache plus papilledema or other signs of intracranial hypertension, focal deficits such as aphasia or paresis often combined with seizures, to severe cases featuring encephalopathy, coma or status epilepticus. The confirmation of the diagnosis of CVT by imaging requires the demonstration of thrombi in a dural sinus or cerebral vein. Currently, CVT is diagnosed with increased frequency due to higher awareness and easier access to magnetic resonance (MR) imaging.

CVT is not associated with classic arterial vascular risk factors. CVT has multiple risk factors, which can be grouped into: (1) transient risk factors, such as oral contraceptives and other medications with prothrombotic effects, pregnancy and puerperium, infections, especially those involving the central nervous system or the paranasal sinus, the ear and the mastoid and (2) permanent risk factors, which are in general prothrombotic medical conditions, including genetic thrombophilic diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome, myeloproliferative disorders and malignancies. In around 13% of adult CVT no risk factors are identified.5

The outcome of CVT patients has been improving over the last decades, not only due to the increase in diagnosis of milder forms of CVT and to improved care, but also due to the substantial decrease of septic CVT.6 Mortality in the Western world is now below 5% and about 80% of the patients make a complete recovery.5 Death is mainly caused by fatal brain herniation, secondary to large hemispheric haemorrhagic infarcts.7 Other deaths are related to the underlying condition, status epilepticus, infection and very rarely to pulmonary embolism. Validated risk scores can be used to help identifying CVT patients with a higher risk of unfavourable outcome.8

Treatment of CVT includes: (1) aetiological treatment or removal of the identified risk factors, (2) antithrombotic treatment and (3) symptomatic treatment of intracranial hypertension, seizures and other complications. Evidence to support diagnostic and treatment decisions is accumulating but is still scarce. For recent comprehensive reviews on CVT see Martinelli,9 Ferro and Canhão,10 Coutinho11 and Ferro et al.12