Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Imaging Modalities for Evaluation of Intestinal Obstruction [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021 Jul;34(4):205-218. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729737. Epub 2021 Jun 2.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

It is essential for the colon and rectal surgeon to understand the evaluation and management of patients with both small and large bowel obstructions. Computed tomography is usually the most appropriate and accurate diagnostic imaging modality for most suspected bowel obstructions. Additional commonly used imaging modalities include plain radiographs and contrast imaging/fluoroscopy, while less commonly utilized imaging modalities include ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Regardless of the imaging modality used, interpretation of imaging should involve a systematic, methodological approach to ensure diagnostic accuracy.

Keywords: abdominal radiography; bowel obstruction; computed tomography; contrast enema; imaging; large bowel obstruction; magnetic resonance imaging; small bowel follow-through; small bowel obstruction; ultrasound.

____________________________________________

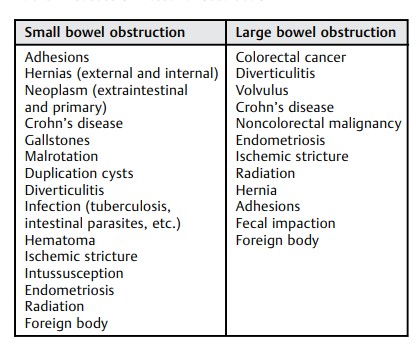

Intestinal obstruction is a clinical scenario commonly encountered by colorectal surgeons, 1 and it is important to understand the evaluation and management of patients with both suspected small bowel obstruction (SBO) and large bowel obstruction (LBO). Approximately 75% of all mechanical bowel obstructions occur in the small bowel. 2 3 SBO occurs in 10% of patients within 3 years following colectomy 4 and in up to 25% of patients after restorative proctocolectomy. 5 Multiple colorectal surgery–related pathologies can result in SBO, including postoperative adhesions, Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, and parastomal hernias, among others. Evaluation and management of LBO can be a complex problem that challenges even the most experienced clinicians. 6 Common etiologies of both SBO and LBO are listed in Table 1 .

Diagnostic imaging is an essential aspect of the modern management of both LBO and SBO. While history and physical exam remain the backbone of evaluation, clinical assessment alone lacks accuracy for bowel obstruction diagnosis and guidance of management. 7 8 9 Imaging helps answer a variety of key questions in patients with suspected obstruction, including the following: 10 11

Answers to these key questions help guide the surgeon to make critical judgments about both operative and nonoperative management. Given the importance of imaging in the evaluation of suspected bowel obstruction, the colorectal surgeon must strive to be adept in the interpretation of all available modalities of bowel obstruction imaging. The surgeon should personally review all imaging and discuss points of ambiguity with the radiologist. This collaboration can result in mutual edification and improvement in patient care, combining the surgeon’s intimate clinical knowledge of the patient with the radiologist’s advanced radiographic expertise. This article will review the available modalities for the evaluation of suspected mechanical intestinal obstruction in the context of the three questions above.

___________________________________________

Plain Radiographs

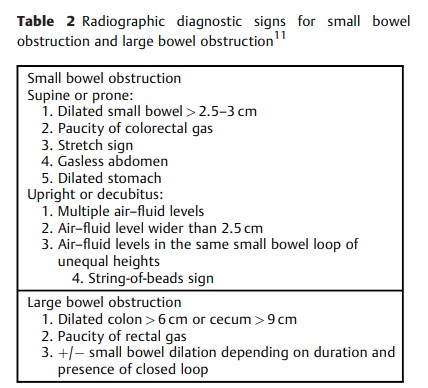

Traditionally, plain abdominal radiographs have been recommended as the initial imaging modality for suspected obstructions due to the speed of acquisition, low cost, wide availability, and low radiation exposure. Plain X-rays can in many cases quickly provide the diagnosis of an obstruction, distinguish SBO versus LBO, rule out pneumoperitoneum, and, in a subset of cases, identify the cause of obstruction, such as colonic volvulus or gallstone ileus.

However, the accuracy of plain radiographs in the diagnosis of bowel obstruction ranges from only 50 to 80%. 12 Additionally, in only a minority of cases do plain abdominal radiographs provide a clear etiology of an obstruction. Plain radiographs are poor at identifying closed loop or strangulated obstructions in the setting of SBO, and the specificity of plain radiographs for LBO is only moderate, in part due to mimicry of acute colonic pseudoobstruction causing false positives. 13 Therefore, even when plain abdominal radiographs appear to definitively establish a diagnosis, obtaining additional information via computed tomography (CT) is often still necessary.

Abdominal radiographs can be obtained as singular images or as a series of films. It has been shown that imaging in both dependent (supine or prone) and nondependent (upright or decubitus) positions increases the accuracy of abdominal radiographs. 14 When the possibility of perforation is considered, an upright chest X-ray or lateral decubitus abdominal film should be obtained to evaluate for pneumoperitoneum. Of note, obtaining multiple views can significantly increase patient radiation exposure. For an average patient, the radiation dose from a singular abdominal X-ray is 0.7 mSv, which is 35 times the dose of a singular chest X-ray (0.02 mSv), 15 but still significantly less than the average noncontrast CT abdomen/pelvis (15 mSv). 16

The article has an excellent detailed discussion of the interpretation of plain radiographs.

_____________________________________________

Computed Tomography

As CT technology has improved, the gap in cost, speed, and availability between CT and plain X-ray has diminished. CT accuracy for the diagnosis of both SBO and LBO is greater than 95%. 28 29 30 This has led some to question the traditional approach of using of plain radiographs as the initial imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with suspected bowel obstruction. 8 31 The “Appropriateness Criteria for Suspected Small-Bowel Obstructions,” published by the American College of Radiology (ACR), states that for initial imaging of the patient with suspected SBO, CT abdomen/pelvis is “usually appropriate” while plain radiographs “may also be appropriate.” 32 The use of a multidetector CT is essential, as multiplanar reconstructions and review of axial, coronal, and sagittal images have been shown to increase the accuracy of interpretation. 33 34

When CT is performed to evaluate suspected bowel obstruction, intravenous (IV) iodinated contrast should be administered unless contraindicated. 32 35 The use of IV contrast has not been shown to significantly change the sensitivity of CT for the detection of bowel obstructions, but it can improve assessment for bowel wall ischemia. 36 Enteric contrast should also be administered in certain clinical scenarios. Enteric contrast agents used for CT can be categorized as positive (radiodensity > water), neutral (radiodensity ≈ water), and negative (radiodensity < water; e.g., gas). Most enteric contrast used for CT is water-soluble iodinated-based contrast but dilute barium preparations for CT do exist. 37 Standard barium cannot be used for CT due to its high radiodensity that creates artifacts obscuring images.

Indications for administration of enteric contrast for CT evaluation of suspected bowel obstructions differ depending on the clinical suspicion. In cases of a suspected high-grade SBO, oral contrast prior to CT should generally be avoided. In this setting, retained fluid within the distended small bowel acts as a natural neutral contrast agent allowing for the same diagnostic accuracy as with oral contrast. 36 In fact, positive oral contrast administration may actually decrease the ability to assess for bowel wall ischemia in this setting. 32 The aforementioned ACR Appropriateness Criteria state that “oral contrast used in a known or suspected high-grade SBO does not add to diagnostic accuracy and can delay diagnosis, increase patient discomfort, and increase the risk of complications, particularly vomiting and aspiration.” 32 In patients with suspected low-grade SBO obstruction, the use of positive oral contrast is appropriate and may increase the sensitivity of diagnosis. 32 In patients with indolent or chronic intermittent obstructive symptoms, the use of large volume neutral contrast administered orally or via a nasoenteric tube can also improve accuracy as part of a specific protocol. In cases of suspected LBO, there is a paucity of published data regarding whether oral and/or rectal contrast should be administered, 29 and no apparent society guidelines exist. Administration of oral contrast alone has the disadvantage of a prolonged waiting period prior to opacifying the colon. While rectal contrast may increase patient discomfort, it may help delineate the site of an obstruction or more definitively rule out mechanical obstruction. Rectal contrast should not be administered if there is any suspicion for perforation. If initial CT is obtained without rectal contrast and diagnosis is in question or further clarity regarding the lesion is needed, CT can be repeated with water-soluble rectal contrast 13 without repeat IV contrast or a water-soluble contrast enema can be obtained.

The article has an excellent detailed discussion of the interpretation of computed tomography.