In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders #330 & #331 Inpatient Diabetes with Dr. Dave Lieb

APRIL 25, 2022 By EMI OKAMOTO.

The above are two episodes placed on one web page.

In this post I link and review #330 Inpatient Diabetes Part 1: Insulin regimens, oral hypoglycemics, corrections scales and more!. In tomorrow’s post, #331 Inpatient Diabetes Part 2: DKA, insulin drips, insulin pumps, and CGMs.*

*Links To And Excerpts From The Curbsiders’ #331 Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) with Dr. Dave Lieb

Posted on April 29, 2022 by Tom Wade MD

All that follows is from #330.

Part 1

Dominate inpatient diabetes! In this part 1 of 2, we discuss how to handle oral hypoglycemics, how to choose an initial insulin regimen, the use of correction scale insulin monotherapy, how to titrate insulin, how to use NPH for steroid-induced hyperglycemia (check out this Twitter thread on safe dosing), and how to reconcile diabetes meds at discharge!

Show Segments (Part 1)

- Intro #1, disclaimer, guest bio

- Guest one-liner, Picks of the Week*

- Inpatient diabetes – a bird’s eye view and the goal(s) of therapy

- Management of outpatient diabetes medications

- Inpatient insulin – options and dosing

- Correctional insulin (“sliding scale”)

- A word on the “Diabetic Diet”

- Steroids and hyperglycemia

- Discharge pearls for the patient with diabetes

- Outro #1

Inpatient Diabetes Pearls

- The key to hyperglycemia management is to be proactive and listen to your patient. Set it and forget it just doesn’t work!

- Discharge comes first: An inpatient management plan is only as good as the outpatient plan that comes when the patient is discharged.

- In general, it’s advisable to hold outpatient diabetes medications to avoid drug-drug interactions and potential adverse reactions, such as acute kidney injury. However, this is not a hard-and-fast rule and depends on the patient’s indication for admission, among other things.

- For most patients with diabetes, correctional insulin is not an appropriate monotherapy. Basal-bolus insulin dosing is recommended, except in patients who are very well controlled and may do fine with correctional insulin. Blood glucose in hospitalized patients should generally be kept between 100 and 200 mg/dL.

- Be mindful of steroids and their effect on blood sugar – be prepared to either up-titrate the current insulin orders or consider NPH dosing with steroid doses.

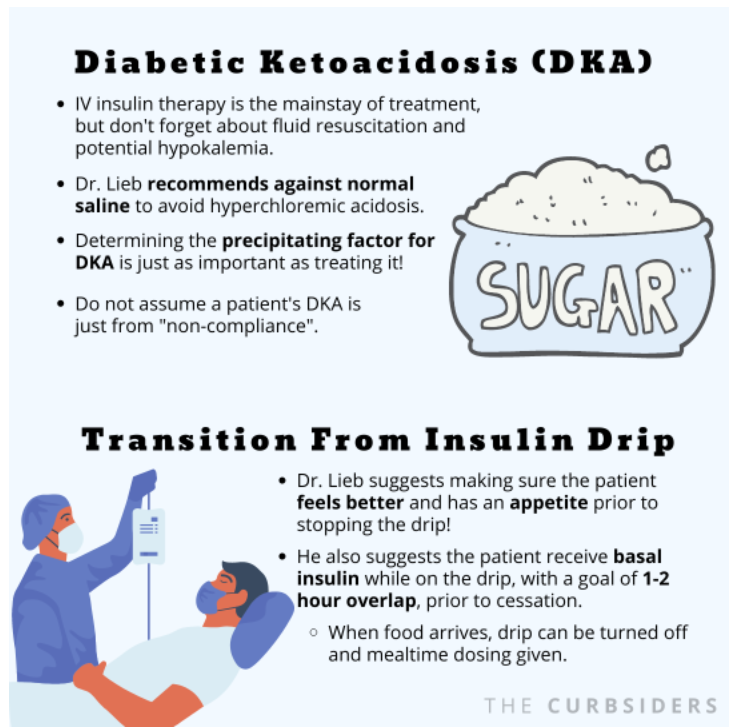

- Mind the gap! Be careful when transitioning patients from insulin drips to basal-bolus dosing.

- If possible (and safe), give your patient the option to continue using their own insulin pump. It may be a patient-centered approach that will build trust between you and your patient.

Inpatient Diabetes – Show Notes

General Thoughts on Diabetes Management in the Hospital

Be proactive!

What will your patient’s discharge plan look like? What can they afford? What kind of education will they need? Regarding education, Dr. Lieb suggests that any opportunity to educate a patient and/or their family should be seized!

Goals of inpatient management:

Dr. Lieb reminds us that context is key! If a patient is undergoing cardiac surgery, tight control may be important. Conversely, if the patient is at high risk for hypoglycemia, tight control may be deleterious. Patient-centered care is a priority when it comes to glucose control.

Dr. Lieb’s Approach to Outpatient Medications in the Hospital:

Medications that a patient takes routinely at home may introduce side effects or confound the overall treatment plan for a patient during their admission. Admissions can often be unpredictable regarding procedures or the general ebbs and flows of a patient’s course. Therefore, stopping home diabetes medications (oral and injectables) and placing the patient on an insulin-only regimen can often be the safest and most flexible means to manage their blood sugar during a hospitalization.

In some cases – for example a prolonged wait for disposition – a patient may be out of the acute phase of their hospitalization and restarting home medications / stopping insulin may be appropriate, on a case-by-case basis.

Remember: It is critically important that the discharge plan is explicit and clear in regards to what to restart, what to hold, and why any changes were made.

Choosing the Right Insulin(s)

An overview

There are a lot of types of insulin out there and the landscape is ever-changing! Insulin helps you in three basic ways: Low-level insulin (i.e. basal) that suppresses hepatic glucose production between meals and overnight, mealtime insulin that covers the glucose-spike from a meal (ideally given 20 min prior to mealtime), and correctional insulin that accounts for high blood sugars (i.e. correctional insulin). Dr. Lieb reminds us that, in general, your hospital will have an insulin formulary that limits your choices. However, prior to discharge, the myriad of options can be mind-boggling! Use your hospital pharmacist to help you find the best discharge regimen for your patient (often based upon cost / insurance).

Insulin glargine is a commonly used basal insulin. It has a duration of action of approximately 24 hours. Alternatively, insulin detemir can be used for basal coverage and is particularly helpful in renal dysfunction given its half life of 12-20 hours. Rapid options include insulin lispro or insulin aspart. [Donner & Sarkar, 2019]*

*Insulin – Pharmacology, Therapeutic Regimens, and Principles of Intensive Insulin Therapy. Last Update: February 23, 2019: “This chapter reviews the pharmacology of available insulins, types of insulin regimens, and principles of dosage selection and adjustment, and provides an overview of insulin pump therapy. For complete coverage of this and related aspects of Endocrinology, please visit our FREE web-book, www.endotext.org.”

A note on rapid-acting insulin: Given the risks of hypoglycemia and the unpredictabilities of inpatient medicine, it may be reasonable (although not optimal) to dose mealtime insulin immediately when food is served or afterwards.

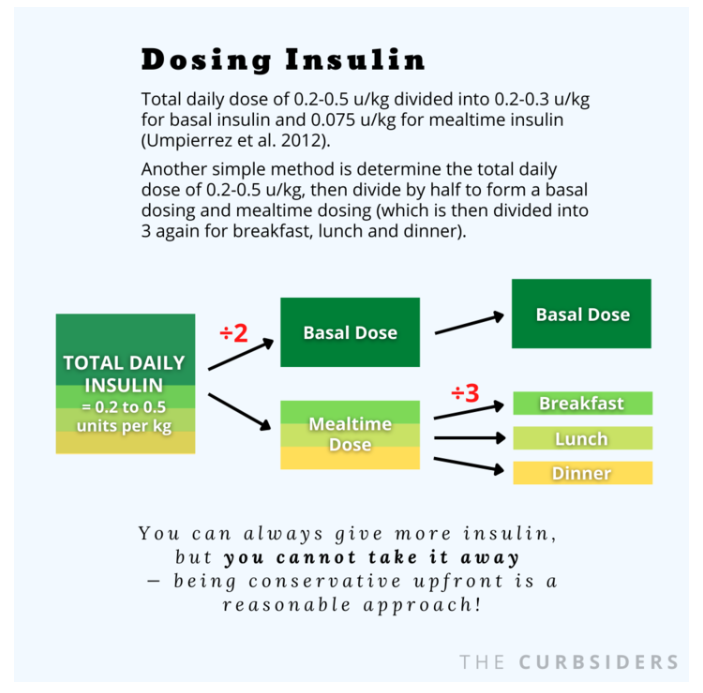

An approach to dosing

Dr. Lieb recommends a multi-factorial approach to determining insulin dosing. Is the patient well-controlled or not? How sick are they? What do they weigh? A lot of hospitals will have weight-based order sets that can set you up for success – although they may need a bit of tailoring. For example: a total daily dose of 0.2-0.5 u/kg divided into 0.2-0.3 u/kg for basal insulin and 0.075 u/kg for mealtime insulin [Umpierrez et al, 2012]. Dr. Lieb reminds us that you can always give more insulin, but you cannot take it away – being conservative upfront is a very reasonable approach!

A few other thoughts from Dr. Lieb: If a patient is on insulin at home, you can start from there and adjust as needed. You may consider decreasing home insulin by 15-20% in a patient who is eating poorly, which is what Dr. Lieb does in his own practice. Also, a simple way to determine dosing may be to use the 0.2-0.5 u/kg daily dosing to determine a total, and simply divide that in two yielding basal dosing and mealtime dosing (which would be divided in three to account for breakfast, lunch and dinner). Another consideration, per Dr. Lieb, is that if you are using insulin in a more tenuous patient or someone who is insulin naive, providing less mealtime insulin than initially calculated may be a prudent approach. For example, if half of the total daily insulin is 30u, normally that would be split into 10u with each meal, however, opting for 4-6u may be safer (i.e. less likely to cause hypoglycemia) in certain circumstances.

What about bedtime insulin? While this is common practice in some institutions, Dr. Lieb recommends against this. Instead, it is safer to watch these patients initially and determine if they would benefit from a dose of rapid acting insulin before bedtime. Instituting this by default can precipitate nocturnal hypoglycemia!

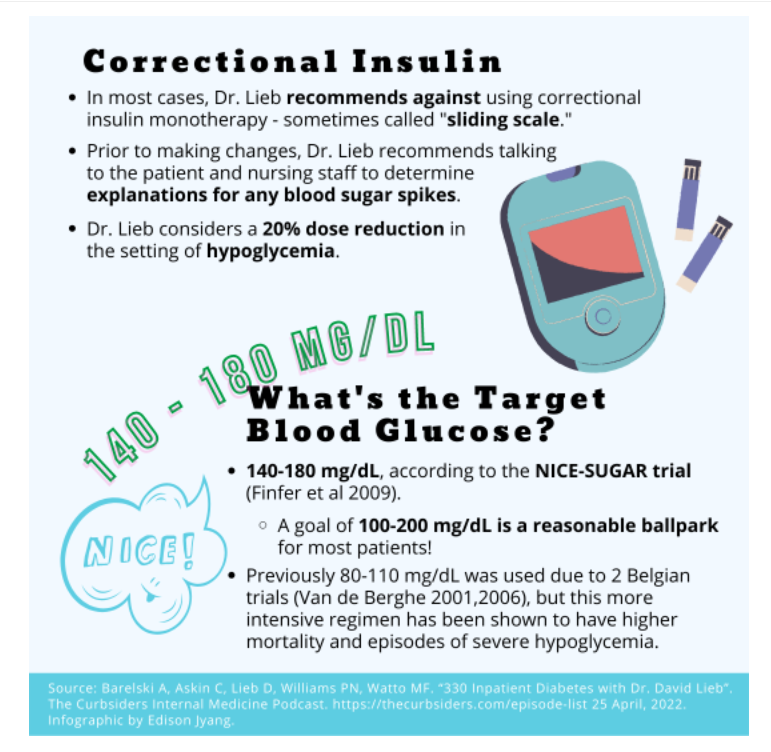

Correctional Insulin & Titration

Dr. Lieb recommends against using correctional insulin monotherapy – sometimes called “sliding scale,” in most cases [Ambrus & O’Connor 2018]. Correctional insulin should be used to correct hyperglycemia, and then a portion of the total daily correctional can be added to the next day’s basal-bolus regimen to achieve better glycemic control. Prior to making changes, Dr. Lieb recommends talking to the patient and nursing staff to determine if there is an explanation for any blood sugar spikes (for example, an unexpected late night snack). Overall, the titration of insulin in the inpatient setting is dynamic and requires the medical team to be deliberate and collect collateral information while making adjustments. However, hypoglycemia requires decisive down-titration of insulin given that the risks of hypoglycemia are significant. Dr. Lieb might consider a 20% dose reduction in the setting of hypoglycemia.

What’s the target?

Dr. Lieb recommends a multi-factorial approach to determining insulin dosing. Is the patient well-controlled or not? Historically, a goal of 80-110 mg/dL had been used by many in the early 2000s based upon two studies out of belgium: one in a surgical ICU and one in a medical ICU [Van de Berghe 2001, 2006]. These studies were criticized as they recruited patients from one center in Belgium. In 2009 the famous, multicenter NICE-SUGAR trial compared this intensive regimen to a less-intensive regimen which showed improved mortality and far-fewer episodes of severe hypoglycemia in the more liberalized arm, which has since given rise to the 140-180 mg/dL goal [Finfer et al 2009]. Overall, the data shows uncontrolled hyperglycemia and severe hypoglycemia can both lead to morbidity and mortality, thus, a rough/ballpark goal of 100-200 mg/dL is reasonable for almost all-comers.

The “Diabetic Diet”

What is it?

The “diabetic diet” in most hospitals is a carbohydrate controlled meal, which theoretically makes it easier to dose insulin. However, patients may often eat additional carbohydrates that can make dosing difficult. Dr. Watto reminds us that a patient-centered approach may be needed to maintain a productive therapeutic relationship with a patient, given that sometimes the diabetic diet may be frustrating for a patient. Remember, many patients will not maintain the same “diabetic diet” at home and thus, this may create an unrealistic eating environment.

Steroids and Hyperglycemia

Insulin and steroids

Dr. Lieb notes that most of the hyperglycemia seen in association in steroids is post prandial, however, the effect of steroids on a given patient is unpredictable. Given that steroids present a moving target, Dr. Lieb will often utilize a continuous insulin infusion in patients getting high doses of steroids, to try to maintain better glycemic control (stress-dose steroids, transplant rejection doses, for example).

One pearl that Dr. Lieb shares is the use of NPH insulin in conjunction with steroid dosing. The peak-effect of NPH seems to correlate nicely with the peak-hyperglycemia seen with steroid use, based upon the pharmacokinetics of NPH. [Atkinson 2016] An approach published in Endocrine Practice in 2009 recommends an NPH dose equal to the product of the patient’s weight in Kg and 1/100th of their steroid dose up to a max of 0.4 units NPH per Kg body weight [Clore & Thurby-Hay 2009]. For example, a 90 kg patient on 60mg of prednisone would get [90 x (40/100)] = 36 units of NPH, just to cover the steroid effect. Another more recent article recommends a max initial dose of 0.3 units NPH per Kg body weight (Aberer 2021)*. Dr. Lieb says it may be prudent to start with a lower dose of NPH if you are concerned for hypoglycemia. He posted this Twitter thread to clarify the point.

*A Practical Guide for the Management of Steroid Induced Hyperglycaemia in the Hospital [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Clin Med. 2021 May 16;10(10):2154.

Discharging from the Hospital

How to transition from hospital glycemic care to the household.

Some patients may need to go home on insulin. If this is likely, Dr. Lieb recommends early education per the diabetes education team, nursing and the medical team. This includes didactic education, as well as practical teaching on insulin pen use, etc. For example, someone on meal time and basal insulin who has been difficult to control will likely need insulin at home. Similarly, a patient on triple-therapy who was poorly controlled and required high doses of insulin as an inpatient will likely need to go home with insulin, and thus appropriate discharge planning is of paramount importance. In the appropriate patient, a combination of basal insulin and other diabetic therapies may both achieve the goal and permit fewer daily injections. Dr. Watto underlines the importance of tailoring the discharge plan to the patient, as the plan is only as good as the follow through.

Now see and review Links To And Excerpts From The Curbsiders’ #331 Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) with Dr. Dave Lieb

Posted on April 29, 2022 by Tom Wade MD