The protocol in this post covers the initial diagnosis and treatment of pediatric seizure in a primary care pediatric office (primary care family practice or internal medicine office). In Resources below there are references on further diagnosis and treatment.

If the child or infant has stopped seizing and the ABCs are stable, then you will need to consider what to do next. Does the patient need an LP, a head CT, laboratory studies, antibiotic and/or acyclovir?

If the patient is still seizing when you walk into the room, then go ahead and call EMS and get started on the protocol. The patient has been seizing for at least five minutes. And the earlier you give the anticonvulsant medicine (and/or glucose if the patient is hypoglycemic) the more effective the treatment will be.

The following suggestion is from The Complete Resource on Pediatric Office Preparedness, Reference (1):

Always check for hypoglycemia with a bedside glucose level. If Glucose level < 60 mg/dl or <40 mg/dl (neonate) Establish IV access and treat.

The following treatment protocol is from Afebrile Seizures – Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Reference (2) in Resources:

Background to condition:

Most convulsions are brief and self limiting, generally ceasing within 5 – 10 minutes. These seizures do not need immediate management unless they continue beyond this timeframe.

Seizures should be treated immediately in the following situations:

– Child presents actively fitting (cause and duration unknown)

– Known cause warranting more urgent treatment

- Meningitis

- Hypoxic injury

- Trauma

- Underlying cardio-respiratory compromise

Assessment:

Assessment and management need to occur concurrently if the child is actively convulsing.

Key considerations in assessment include:

- Any compromise to ABC?

- Duration of seizure including pre-hospital period?

- Significant past history including seizures, neurological comorbidity including VP shunts, renal failure (hypertensive encephalopathy), endocrinopathies (electrolyte disturbance)?

- Focal features?

- Fever? (Febrile convulsion or CNS infection)

- Anticonvulsant medications including any acute pre hospital treatment?

- Previously successful acute anticonvulsant management?

- Evidence of underlying cause that may require additional specific emergency management?

- Hypoglycemia

- Electrolyte disturbance including hypocalcemia

- Meningitis

- Drug overdose

- Trauma (consider occult head trauma)

- Stroke and intracranial haemorrhage

Note:

It is now recognised that some children can have a presentation with convulsions and an acute infectious illness (particularly gastroenteritis) without documented fever. This is sometimes referred to as ” afebrile febrile convulsions”. The management and prognosis is the same as for classical febrile convulsions.

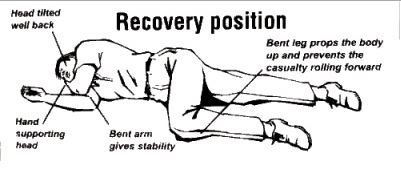

If the patient vomits, suction and place in the recovery position.

Acute Management:

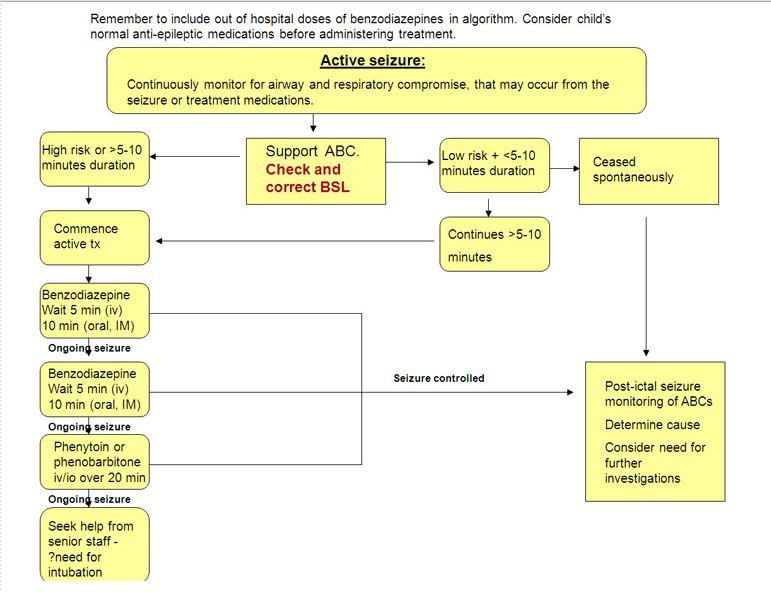

In most situations (see above) supportive care for 5 – 10 minutes is appropriate. Ensure adequate airway and breathing while waiting for convulsion to stop spontaneously.

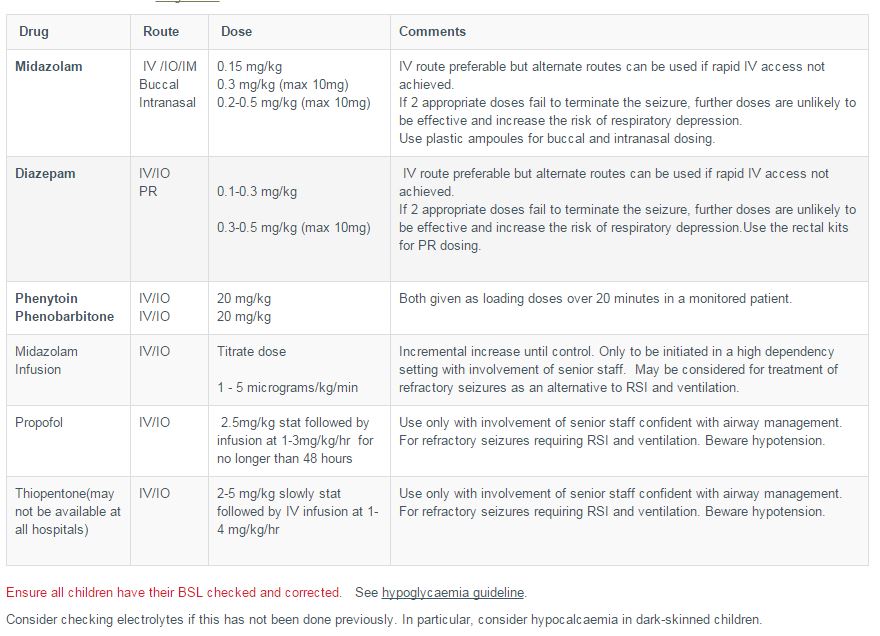

If seizure persists or the onset has not been witnessed, pursue active management (see management algorithm and drug dose table). Include benzodiazepines given on the way to hospital (eg by parents or paramedics) when using this algorithm.

- Support airway and breathing, apply oxygen by mask, monitor.

- Secure IV access, check bedside BSL and send urgent specimen for calcium / electrolytes and venous blood gas. If hypoglycaemia present, also see Hypoglycaemia guideline and correct the low sugar. Give benzodiazepine.

- Repeat benzodiazepine after 5 minutes of continuing seizures.

- If convulsion continues for a further 5 – 10 minutes, commence IV phenytoin or phenobarbitone. If IV access cannot be secured and seizures refractory to benzodiazepines, consider IO access.

- Consider pyridoxine (100mg IV) in young infants with seizures refractory to standard anticonvulsants.

- Seek senior assistance if seizure not controlled. Anticipate need to support respiration. Thiopentone or Propofol and rapid sequence induction (RSI) may be required for seizure control.

Resources:

(1) The Complete Resource on Pediatric Office Emergency Preparedness. 2013. Springer. This excellent book is brief and to the point. The authors are from Texas Children’s Hospital and Texas Children’s Pediatrics. pp 31 – 32.

(2) Afebrile Seizures – Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Clinical Practice Guidelines.

(3) The Harriet Lane Handbook, Twentieth Edition, Elsevier Saunders, 2015. Status Epilepticus, pp 15 – 16

(4) Seizures – safety issues and how to help – parent and caretaker information from Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Kids Health Info Fact Sheets

(5) Pediatric First Seizure Updated: Sep 17, 2015. Emedicine Medscape