For all of the recommendations of Reference (1), see the executive summary p 1 – 14.

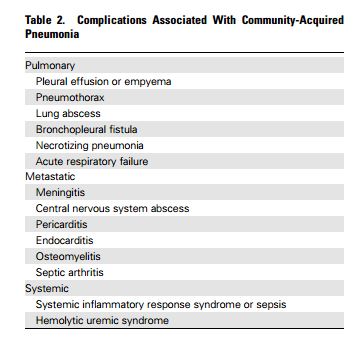

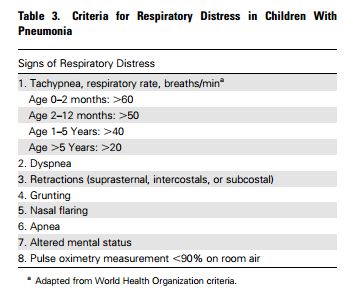

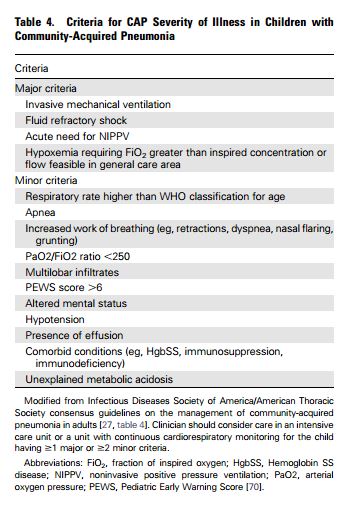

The following are from Reference (1), The Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older Than 3 Months of Age: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America:

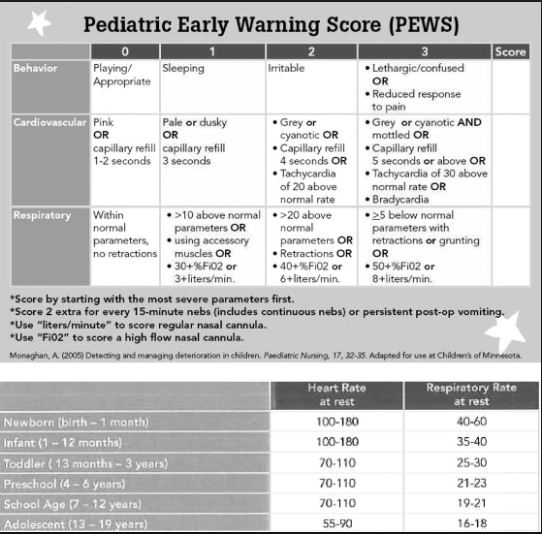

And here is a chart on the PEWS score referenced in table 4 above:

___________________________________________________________

What follows is some quotes from Reference (2) below:

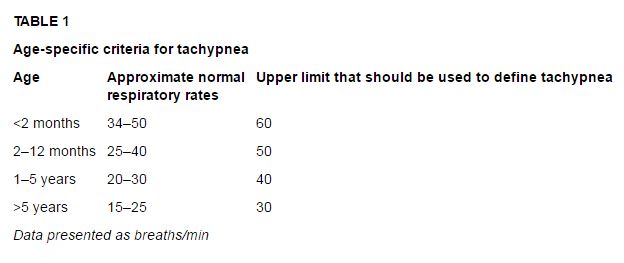

Children typically experience fever and tachypnea (determined by counting the respiratory rate for 60 s in a calm state) (Table 1). Indrawing, retractions and/or a tracheal tug indicate respiratory distress (dyspnea). Measurement of oxygen saturation with pulse oximetry is indicated in all patients presenting to a hospital or with significant illness because hypoxemia may not be clinically apparent and cyanosis is only associated with severe hypoxemia. However, a normal oxygen saturation does not exclude the possibility of pneumonia.

Imaging

Radiographs are not indicated for children experiencing wheezing with a typical presentation of bronchiolitis or asthma because bacterial pneumonia is very unlikely. When bacterial pneumonia is suspected clinically (a febrile child with acute respiratory symptoms and physical findings compatible with consolidation or pleural effusion), a chest radiograph (both postero-anterior and lateral) should usually be obtained.

The reason for imaging is that the clinical features of other conditions overlap with bacterial pneumonia, and antibiotics may be avoided if the chest radiograph does not suggest bacterial pneumonia.[7] However, in cases where the diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia is highly suspected from history, combined with typical clinical and physical findings and the child is not sufficiently ill to require hospitalization, a chest radiograph is not essential. All hospitalized children should have a chest radiograph performed to assess the extent of pneumonia and determine the presence of pleural effusion or abscess.

Ultrasound at the point of care appears to be sensitive and specific for detecting pneumonic infiltrates but requires further validation.[9] Ultrasound and computed tomography are also useful in the diagnosis of complicated pneumonia. Both will detect parapneumonic effusions, which often accompany uncomplicated pneumonia, as well as empyemas, where persistent fever is a predominant symptom. Culture and drainage of a pleural effusion is indicated if the effusion is large and/or is clinically important as a cause for respiratory compromise or when response to medical therapy alone is not satisfactory.[10]

Guidelines for referral to hospital or hospital admission

Most children with pneumonia can be managed as outpatients. Specific paediatric criteria for admission are not available. Hospitalization is generally indicated if a child has inadequate oral intake, is intolerant of oral therapy, has severe illness or respiratory compromise (eg, grunting, nasal flaring, apnea, hypoxemia), or if the pneumonia is complicated. There should be a lower threshold for admitting infants younger than six months of age to hospital because they may need more supportive care and monitoring, and it can be difficult to recognize subtle deterioration clinically.

Management

If influenza is detected or suspected, strong consideration should be given to prompt treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir). Treatment with antivirals has been shown to provide benefit and may prevent secondary bacterial infections, particularly in hospitalized or moderately to severely ill children.[12]-[14] When other viruses are detected in a nasopharyngeal sample and/or the chest radiograph is most compatible with viral pneumonia (ie, without consolidations), manage with supportive care (ie, oxygen and rehydration if required) without antibiotics, unless there is convincing evidence of a secondary bacterial pneumonia.

The primary goal of antimicrobial therapy, for the vast majority of uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonias, is to provide good coverage for S pneumoniae, because molecular-based techniques have shown this to be the predominant bacterial pathogen.[15]-[17] Therefore, outpatients with lobar or broncho-pneumonia should usually be treated with oral amoxicillin. Patients who require hospitalization but do not have a life-threatening illness should usually be started empirically on intravenous ampicillin. There is recent data demonstrating that ampicillin alone leads to a good clinical outcome in almost all cases of community-acquired pneumonia, including cases that require hospitalization.[18]-[20]

Children who experience respiratory failure or septic shock associated with pneumonia should receive empiric therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin because it offers broader coverage. Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime offer better coverage than amoxicillin or ampicillin for beta-lactamase-producing H influenzae and may be more efficacious against high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococcus – and possibly provide empirical coverage for the rare methicillin-susceptible S aureus (a rare cause of pneumonia).[21] However, when there is rapidly progressing multilobar disease or pneumatoceles, the addition of vancomycin is suggested empirically to provide extra coverage for MRSA until culture results are available. If results of microbiological investigations in these patients do not reveal a pathogen, transitioning to ampicillin with subsequent oral amoxicillin is reasonable.

_________________________________________________________

Here is a YouTube videos demonstrating the ultrasound evaluation of pediatric pneumonia:

Ultrasound of Pediatric Pneumonia

_______________________________________________________

Resources:

(1) The Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older Than 3 Months of Age: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53(7):e25-76. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir531. Epub 2011 Aug 31.

(2) Uncomplicated pneumonia in healthy Canadian children and youth: Practice points for management[Full Text HTML] 2015.

(3) Revised WHO classification and treatment of childhood pneumonia at health facilities [Full Text PDF] 2014. [These recommendations are most appropriate in resource limited areas]

(4) Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: a meta-analysis [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Pediatrics. 2015 Apr;135(4):714-22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2833. Epub 2015 Mar 16.

(5) Prospective Evaluation of Point-of-Care Ultrasonography for the Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Children and Young Adults [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF available for download]. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):119-125. doi:10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.107

(6) Usefulness of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in children [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015 Feb;56(1):40-5. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.03.007. Epub 2014 Jul 15.

(7) Application of Lung Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Childhood Lung Diseases [PubMed Abstract [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PubReader]. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015 Oct 5;128(19):2672-8. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.166035.