Children and adults who are on a ketogenic diet require careful and thorough evaluation when they exhibit acute illness. Please see clinical guideline Ketogenic diet acute illness management from The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Although the guideline is for children, the same management principles would apply for adults.

This post consists of excerpts from the 2018 Guidelines [Resource (1)] Optimal clinical management of children receiving dietary therapies for epilepsy: Updated recommendations of the International Ketogenic Diet Study Group [29881797]:

Key Points

• This manuscript represents a re-evaluation of ketogenic

diet best practices, 10 years after the previous

guideline publication

• Ketogenic diets should be used in children after 2 antiseizure

drugs have failed, and for several epilepsy syndromes

perhaps even earlier

• There are 4 major ketogenic diets, and the one chosen

should be individualized based on the family and child

situation

• Flexibility in the initiation of ketogenic diets is appropriate,

with fasting and inpatient initiation optional

• Children should be seen regularly by the ketogenic

diet team, along with labs and side effect monitoring

at each visit.Ketogenic dietary therapies (KDTs) are well-established,

nonpharmacologic treatments used for children and adults

with medication-refractory epilepsy. . . . There are currently 4

major KDTs: the classic KD, the modified Atkins diet

(MAD), the medium chain triglyceride diet (MCT), and the

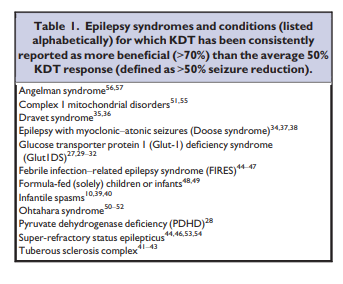

low glycemic index treatment (LGIT).There are several specific conditions for which the group

considered that KDTs should be used early in the course of

epilepsy management (Table 1).Preliminary experience also showing some beneficial

effects of the KD has been reported in epileptic encephalopathies

such as Lafora body disease,58 Rett syndrome,59,60

Landau-Kleffner syndrome,61 and subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis (Table 2).62 Single reports describe the use

of the diet in metabolic disorders such as phosphofructokinase

deficiency, adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, and

glycogenosis type V.63–65 Other conditions with limited

data include juvenile myoclonic epilepsy,66 CDKL5

encephalopathy,67 epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal

seizures,68 childhood absence epilepsy,69 and epileptic

encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during

sleep.70All of the above strong and moderate indications have

sufficient data in our guideline group’s opinion to justify the

use of KDT. However, are these reports enough to justify

early or even first-line use? Many of these conditions have

comorbid cognitive or behavioral abnormalities; would

KDT ameliorate these issues as well? In addition, several of

these indications have “preferred” ASDs (eg, valproate and

clobazam for Dravet syndrome, corticosteroids and vigabatrin

for infantile spasms). Does KDT work synergistically

with these ASDs for these particular conditions? These

important questions should be investigated in the years to

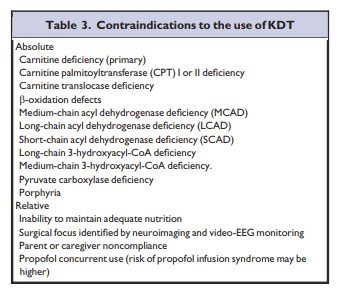

come.KDTs are contraindicated in several specific disorders

(Table 3). The metabolic adaptation to KDT involves a shift

from use of carbohydrates to lipids as the primary energy

source. As such, a patient with a disorder of fat metabolism

might develop a severe deterioration in the setting of fasting

or KDTs. Therefore, before initiating the KDT, a child

should be screened for disorders of fatty acid transport and

oxidation if there is clinical concern for one of these conditions,

especially in the setting of epilepsy without a clear

etiology.Before starting KDT, one should consider inborn errors of metabolism that could lead to a severe metabolic crisis and ruled out if there is a clinical suspicion for these disorders.

Pre-diet evaluation and counseling

A clinic visit prior to initiation of KDT is strongly

advised. The goals of this visit are to identify the seizure

type(s), rule out metabolic disorders that are contraindications

to KDT, and evaluate for complicating comorbidities (presence of kidney stones, swallowing difficulty, hypercholesterolemia, poor weight gain or oral intake, gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, cardiomyopathy, and chronic metabolic acidosis [Table 4]). Neurologists should review all current medications in partnership with a pharmacy and/or internet-based guides to determine carbohydrate content and options of switching to lower carbohydrate preparations while the patient is on KDT. [See Resource (2) below]Screening laboratory studies should be obtained prior to

starting KDT (Table 4).

Renal ultrasounds are advised only if there is a family history of kidney stones. A comprehensive evaluation should be undertaken if no clear etiology for the patient’s epilepsy has been identified. Electroencephalography and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential to identifying those patients who are possible surgical candidates.

A key component of KDT is the information the family

receives prior to the initiation of the diet. Helpful resources

for families include publications, websites, and videos from

support groups such as The Charlie Foundation [For Ketogenic Therapies] and Matthew’s Friends [Ketogenic Dietary Therapies] .6–8The expected length of time on KDT should be discussed [with the family]. A minimum of 3.2 months (SD 1.3) to allow for potential improvement to occur is advised.

Short-term difficulties are not uncommon at the time of KDT initiation and should be discussed with families; those occurring during the first week of the KD do not portend poor efficacy later.79 A social worker or nurse on the team can be instrumental in helping the family transition to KDT by assessing family needs, financial limitations, and gathering

resources, and contacting other families on KDT for parent-to-parent support.Specific diet selection and provision

There are 4 major KDTs with published evidence supporting

their use. The first 2 created, the classic long-chain

triglyceride (LCT) KD and the medium-chain triglyceride

(MCT) diet, have been in existence the longest and are typically

started in the hospital by a dietitian and neurologist. The LCT diet has been the more traditional KD treatment, for which most data are available, and is used by every center in this consensus group. The MCT diet may be preferable in some cases.81–84 In the classic KD, the fat source is predominantly LCT, which is obtained primarily from standard foods. MCT oils yield more ketones per kilocalorie of energy than LCTs. This increased ketogenic potential means less total fat is needed in the MCT diet, thus allowing the inclusion of more carbohydrate and protein and potentially food choices. There is no evidence for different efficacy between the MCT and classic KD (Class III

evidence).82,83The classic KD is calculated in a ratio of grams of fat to

grams of protein plus carbohydrate combined. The most

common ratio is 4 g of fat to 1 g of protein plus carbohydrate

(described as “4:1”); 90% of calories are from fat. A 3:1 or lower ratio can be used alternatively to increase protein or carbohydrate intake; this is more appropriate as well for diet initiation in infants. There is one publication reporting that a 4:1 ratio, when used at initiation, may be more advantageous for the first 3 months in older children, after which the ratio can be reduced.85The traditional MCT diet is used by 10 (40%) of the consensus

ketogenic diet centers and comprises 60% energy from MCT. This level of MCT can cause gastrointestinal discomfort in some children. To improve this difficulty, a modified MCT diet was created, using 30% energy from MCT oil, with an additional 30% energy from long chain fats.82 Many children will be on a 40–50% energy MCT diet, and can tolerate as high as 60% if necessary. MCT oil has also been used as a supplement to the classic KD to boost ketosis, improve lipid abnormalities, and due to laxative properties. MCT can be given in the diet as coconut oil or as an emulsion. MCT should be included in all meals

when used. Better toleration may be achieved using lessMCT with each meal but providing more meals per day. MCT oil consumption may also cause throat irritation due to the presence of C6 (caproic acid).88In the past 16 years, 2 other dietary therapies have been

developed for the treatment of epilepsy: the Modified Atkins Diet (MAD) and Low Glycemic Index Treatment (LGIT).24,25,89,90 Both of these KDTs are initiated universally as outpatients and they do not require precise weighing of food ingredients. They tend to require less dietitian time for meal calculations and allow more parental independence. The MAD is offered by 23 (92%) of consensus ketogenic centers and the LGIT by 17 (68%).The MAD is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate therapy similar

to the classic KD in food choices, and typically provides

approximately a 1:1–1.5:1 ketogenic ratio, but no set ratio is

mandated and some children can achieve as high as a 4:1

ratio.24 The initial daily carbohydrate consumption on the

MAD is approximately 10–15 g (comparable to the strict

initiation phase of the Atkins diet used for weight loss), with

a possible increase to 20 g per day after 1–3 months.90

However, there is no limitation on protein, fluids, or calories,

making meal planning easier. In addition, as detailed

calculations are not required, this diet may be ideal for low resource settings with a paucity of trained dietitians.The MAD has been shown to be effective in children with

refractory epilepsy in a randomized controlled trial (Class

III evidence). . . . For adolescents and adults, the MAD or LGIT is preferred by most (72%) of the consensus group largely due to better adherence.The LGIT was designed based on the hypothesis that

stable glucose levels play a role in the mechanism of the

KD.25 The LGIT allows liberalization of total daily carbohydrate intake to approximately 40–60 g/day, but favors

carbohydrates with low glycemic indices <50. A few uncontrolled studies suggest that the LGIT may be efficacious in

children with refractory epilepsy, but there are no trials comparing the LGIT with other KDTs.94–97 The LGIT has

been reported as particularly effective in children with Angelman syndrome, including a single center case series

of 23 patients.56Committee conclusions

The specific KDT chosen should be individualized based

on the family and child situation, rather than perceived efficacy,

together with the expertise of the KDT center. Calorie

and fluid restriction are no longer recommended. Children

younger than 2 years of age should be started on the classic

KD (Class III evidence), and a formula-based KD may be

helpful for this age group. There is reasonable evidence for

the use of the MCT (Class III), MAD (Class III), and LGIT,

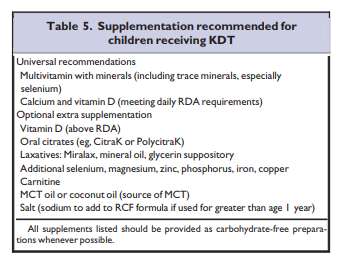

and most consensus ketogenic centers are offering these options for KDT. These latter 2 therapies are recommended for adolescents, but centers may choose the classic KD for individual cases, especially in those with enteral feeding. The MAD is being studied for use in areas with limited resources.Supplementation

Due to the limited quantities of fruits, vegetables,

enriched grains, and foods containing calcium in KDT,

supplementation is essential, especially for B vitamins

(Table 5).Committee Conclusions

All children should receive a daily multivitamin and calcium

with adequate vitamin D. Oral citrates appear to prevent

kidney stones (Class III); however, there was a mixed

opinion on empiric use. Vitamin D levels decrease on the

KD, but again, there were split opinions on empiric extra

supplementation. There is no recommendation for the

empiric use of antacids, laxatives, probiotics, exogenous

ketones, additional selenium, or carnitine with the KD at

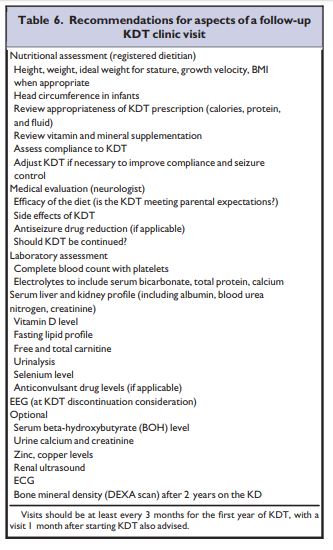

this time.Maintenance of children receiving dietary therapies

Maintenance of children receiving dietary therapies

The child on KDT should be seen regularly for follow-up

evaluation by both dietitians and neurologists familiar with

KDT (Table 6).131,132[Monitoring Of Ketones]

Urine ketones should be checked at home by parents several

times per week, preferably at different times of the day,

as urine ketones can be low in the morning and higher in the

evening. There are data regarding the value of serum BOH

(beta-hydroxybutyrate), with some studies suggesting that

serum BOH may better correlate with seizure control.134–136

Serum ketosis is more accurate, but more expensive and

requires finger sticks. The current guideline for infants on

the KD recommends serum BOH monitoring.14 Several

members of the consensus group suggested that obtaining

serum BOH at routine KDT clinic visits was valuable, especially

during the diet-initiation period, and 44% (11/25) of

the group have parents use home BOH meters. This was

higher than the previous consensus statement (15% recommending

home BOH meters). BOH monitoring may be reasonable

when urine ketones results do not clinically match

seizure control or fluctuate without explanation.In addition to a complete examination with accurate

weight and height measurement at each follow-up visit,

laboratory studies are recommended (Table 6 above).Nutritional ketosis can be adjusted through diet manipulation

to try to improve seizure control. Increasing the

fat content of the diet and lowering the carbohydrate

and/or protein is a method that can be trialled to induce

deeper ketosis. This is known as “increasing the ratio” in

classic KD terminology. Similarly, lowering the fat content

can reduce ketosis which may be desirable when

ketosis is too strong (ie, causing lethargy) or if weaning

KDT. Ketogenic practitioners have occasionally incorporated

MCT oil into the classic KD to achieve higher

ketosis while maintaining the same ratio and for its

added benefit as a laxative effect and easier digestibility

over long-chain fats.Adverse effects

Side effects of KDT occur, and neurologists and dietitians

need to understand how to manage them.129,142,143 The most

common involve the gastrointestinal system and are often

seen during the initial few weeks of dietary therapy. Constipation, emesis, and abdominal pain may occur in up to 50% of children.79,129,144 These symptoms are usually mild and easy to correct with minimal interventions. When adequately managed and prevented, gastrointestinal side effects

are rarely a reason to discontinue KDT.Hyperlipidemia is a well-known side effect of almost all

KDT.137,145–148 Increased serum triglycerides and total and

low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels have been

reported in 14–59% of children on the classic KD.129,137,147,148 Hyperlipidemia can be seen as early as the first month of therapy.148 Preliminary data suggest that despite an early increase in serum lipids during the first months of KDT, this increase is usually temporary. In one study, 60% of those on the classic KD had hypercholesterolemia (>200 mg/dl).147 By 12 months, the serum lipid values often normalize and remain within normal limits.137,149Although the risk for coronary artery disease may

increase with long-term elevations of cholesterol levels,

previous pediatric studies showed no change in the carotid

intima-media thickness compared to baseline at 6 and

12 months of therapy.150,151 On the other hand, local and

systemic arterial stiffness was significantly increased in 2

studies involving children and young adults, correlated with

serum cholesterol and triglycerides levels.152,153 Nevertheless,

long-term vascular outcomes of this high fat diet are

not known.Renal calculi historically have occurred in 3–7% of children

on KDT.115,127,154 They typically do not require KDT

discontinuation and lithotripsy is necessary only rarely.There is mixed data on the effect of KDT on growth in

children. However, all six studies with longer than 6 months

duration indicate that the classic KD has negative effects on

growth, and over time may cause a height deceleration.84,138,139,155–157Cardiac abnormalities have been reported in children on

the KD, including cardiomyopathy and prolonged QT interval.124,125,158,159 The mechanism of these complications is not fully understood; one case was associated with selenium

deficiency, but others were not. As stated previously, routine

ECG is not recommended at this time as a screening

test. Pancreatitis has also been reported.129,160 Hepatic dysfunction may be more likely to occur in children who are on

both valproic acid and KDT, with intercurrent viral illness

furthering increasing the risk of elevated transaminases.112,129,142The long-term complications in children maintained on

KDT for >2 years have not been reviewed systematically;

there is only one report in the literature looking at this small

subgroup.149 In this population, there was a higher risk of bone fractures, kidney stones, and decreased growth, but

dyslipidemia was not identified.149Committee Conclusion

Like all medical therapies KDTs have potential adverse

effects. Overall, the risk of serious adverse events is low;

KDTs do not need to be discontinued for most adverse

effects. Gastrointestinal complaints are often the most common

but can be mostly remedied.Discontinuation

A large percentage, 80%, of children who are seizure-free

on KDT will remain that way after KDT is discontinued.164

The risk may be higher in those with discharges on EEG,

brain malformations, and tuberous sclerosis complex.164 In

a multicenter study from Argentina, seizures recurred in

25% of those who were seizure-free and stopped the KD,

with a median period of follow-up after discontinuation of

the KD of 6 years.144 Many of these children with recurrent

seizures had brain lesions and EEG abnormalities.144

Resources:

(1) Optimal clinical management of children receiving dietary therapies for epilepsy: Updated recommendations of the International Ketogenic Diet Study Group [Pubmed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3(2):175-192. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12225. eCollection 2018 Jun.

(2) Medication Management On The Ketogenic Diet [Link is to the PDF]. By Jeff Curless, Pharm.D. Clinical Pharmacy Resident CHOC Children’s Hospital Email: jcurless@choc.org. Medications (pills) can have a lot of carbs in them. Dr. Curless explains how to deal with this problem.

(3) Ketogenic diet acute illness management, Clinical Guidelines (Nursing) from the Royal Children’s Hospital Of Melbourne. Updated November 2015.