Today I reviewed, linked to, and embedded the Addiction Medicine Podcast‘s* #4 Wrapping Our Heads Around Alcohol Use Disorder Meds*. July 28, 2022 | By Zina Huxley-Reicher

*Link is to the complete episode list of the Addiction Medicine Podcast.

**Huxely-Reicher Z, Peterkin, A, Cohen S, Mullins K, Chan, CA. “#4Wrapping Our Heads Around Alcohol Use Disorders Meds w/Dr. Alyssa Peterkin”. The Curbsiders Addiction Medicine Podcast. http://thecurbsiders.com/addiction July 28th, 2022.

All that follows is from the above resource.

AUD Pharmacotherapy Pearls

- Only about 2% of patients with AUD are actively receiving treatment and medications for AUD work!

- There is good evidence that reducing alcohol use (NOT just total abstinence) improves health outcomes, reduces mortality, and improves the quality of life.

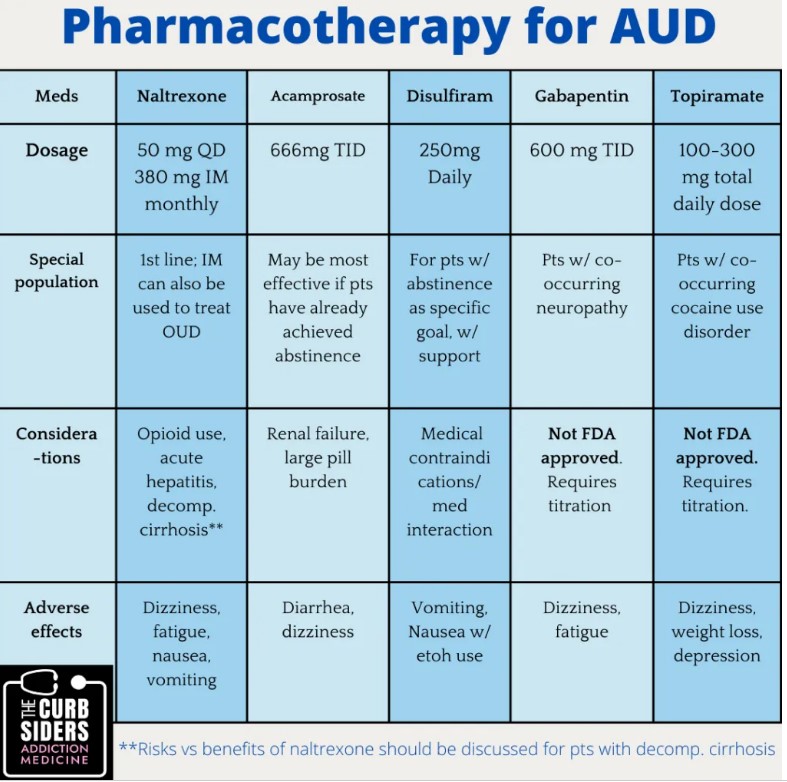

- FDA-approved medications for AUD include naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Naltrexone is first-line for most patients unless they have active opioid use of any kind or acute hepatitis. For patients with decompensated liver disease, a discussion of the risks vs. benefits of the medication should occur. Acamprosate is contraindicated for patients with GFR <30.

- If a patient does not have clinical signs of decompensated liver disease, the need to check LFTs should not delay the start of naltrexone treatment.

- Topiramate and gabapentin can be considered for off-label treatment of AUD in some cases.

- Many types of psychosocial support and/or treatment exist to support patients with AUD – if you do not feel comfortable helping your patients navigate these resources, find out who in your healthcare system you can refer to for assistance.

Diagnosing Alcohol Use Disorder

Take an alcohol use history – Dr. Peterkin recommends starting with general questions about how much a patient drinks in one sitting and how often in a week. Unhealthy alcohol use includes both binge drinking and heavy drinking. Binge drinking means exceeding daily limits – 4 or more drinks consumed on one occasion for women, or 5 or more drinks consumed on one occasion for men. Heavy drinking means exceeding weekly limits – 8 or more drinks or more per week for women, or 15 or more drinks per week for men (CDC 2019).

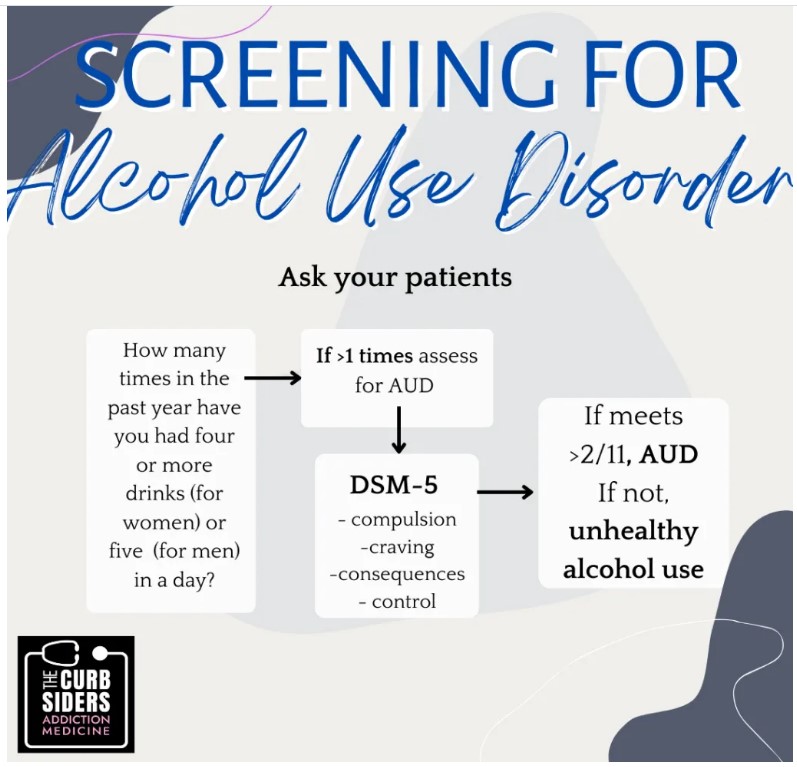

Assess whether a patient meets the criteria for unhealthy use or alcohol use disorder (AUD) using the following tools:

- First, use a single-item, calendar-based screener that is validated in primary care settings (Smith, 2009). Ask “How many times in the past year have you had X or more drinks in a day?”, where X is 5 for men and 4 for women. A response of >1 means that the patient meets the criteria for unhealthy alcohol use.

- Other screening tools include the AUDIT and AUDIT-C, but these are lengthier so they might be less user-friendly. The CAGE questionnaire has low sensitivity for detecting mild cases of unhealthy use (Dhalla, 2007).

- Next, assess for AUD using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (NIAAA, 2021). These eleven criteria determine whether someone has experienced problems related to alcohol use. If a patient answers yes to two or more criteria, then they carry a diagnosis of AUD. Depending on the number of criteria that a patient meets, you can diagnose a mild, moderate, or severe use disorder. The criteria are included below.

11 – DSM-V Criteria

- Substance is taken in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain, use or recover from its effects

- Craving, or a strong desire to use the substance

- Recurrent substance use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

- Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of substances

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use

- Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous

- Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by substance

- Tolerance (defined as a need for markedly increased amounts of substance to achieve intoxication or desire effects, OR markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of a substance)

- Withdraw

Defining a standard drink:

Patients (and providers) may not have a great sense of what a standard drink is, so we need to clarify units to quantify use. Use familiar metrics such as a bottle of wine or 12-ounce beer. Walk through this visual tool with patients or with this interactive tool where a patient “pours” their drink can help.

Identifying patient goals:

First and foremost, it is essential to help your patient articulate their specific goals concerning their drinking in a patient-centered way. Aim to meet patients where they are at. Ask your patient – what do you want to do here? What are your goals? Do you want to cut down? How much, in what time frame? Often patients may be pre-contemplative about making changes to their alcohol use – this is an opportunity to use motivational interviewing techniques. Ask patients what they enjoy about drinking, what they dislike, and how they think it has impacted their health. These questions are helpful to explore in both the hospital and outpatient settings because you can offer treatment from either location.

Remember that abstinence is not the only successful outcome – evidence supports that reducing use is associated with improved health outcomes and quality of life and can be sustainable for some people. (Witkiewitz, 2018) (Witkiewitz, 2017) (Witkiewitz 2021) (Falk, 2019).

Identifying patient goals:

First and foremost, it is essential to help your patient articulate their specific goals concerning their drinking in a patient-centered way. Aim to meet patients where they are at. Ask your patient – what do you want to do here? What are your goals? Do you want to cut down? How much, in what time frame? Often patients may be pre-contemplative about making changes to their alcohol use – this is an opportunity to use motivational interviewing techniques. Ask patients what they enjoy about drinking, what they dislike, and how they think it has impacted their health. These questions are helpful to explore in both the hospital and outpatient settings because you can offer treatment from either location.

Remember that abstinence is not the only successful outcome – evidence supports that reducing use is associated with improved health outcomes and quality of life and can be sustainable for some people. (Witkiewitz, 2018) (Witkiewitz, 2017) (Witkiewitz 2021) (Falk, 2019).

Explaining AUD to patients-

Dr. Peterkin makes sure to frame addiction to patients as a chronic disease, NOT as a choice or a moral failing. People choose to use substances for many reasons, and genetic and psychosocial factors influence their responses. Substance use disorders involve uncontrolled use despite negative consequences. Patients may express that they plan to stop right now; Dr. Peterkin advises digging deeper to help patients develop concrete plans.

Pharmacotherapy for AUD:

AUD is severely undertreated. Roughly 2% of patients with AUD are prescribed pharmacotherapy (Joudrey 2019) (Harris 2012). Offer pharmacotherapy in inpatient and outpatient settings (Wei, 2015) (Joudrey 2019). Three medications (naltrexone, acamprosate and disulfiram) have FDA approval to treat AUD. Off-label options include topiramate and gabapentin.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is the first-line medication for AUD for most patients. Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist and is contraindicated for patients who use opioids (including prescription pain medication, heroin, methadone, or buprenorphine) and do not plan to stop their use. Naltrexone comes in an oral formulation with a dosage of 50 mg or an IM form of 380 mg that is injected monthly.

Dr. Peterkin recommends starting at 25 mg (½ dose) for 3 days and then increasing to 50 mg daily. It has a number needed to treat of 12 for return to heavy drinking and 20 for return to any drinking, which is comparable to (or better) than medications we use every day to treat other chronic conditions (e.g., statins, SSRIs) (Jonas 2014). Common side effects include dysphoria, fatigue, headache, and GI side effects. If patients experience fatigue or dizziness, they can take the naltrexone at night or take it with food if they experience GI side effects (which typically resolve after the first few days). Of note, IM naltrexone does not undergo first-pass metabolism in the liver, which theoretically gives it a lower risk of hepatotoxicity, yet this lacks a real-world comparison (SAMHSA, 2009).

In addition to opioid use, acute hepatitis or acute hepatic failure is a contraindication. For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, the risks vs benefits of using the medication should be discussed with the patient and hepatologist. Naltrexone is generally safe to use and can be considered in decompensated cirrhosis with close monitoring, particularly since reducing alcohol use is so essential to maintaining liver function. Often, initiating naltrexone will improve LFTs in patients with alcohol-related liver disease (Augustin, 2022). Clinically monitor a patient taking naltrexone for signs of liver disease. Still, a patient does not necessarily need baseline LFTs or routine monitoring to start or continue the medication – in fact, the absence of these labs should not prevent you from starting the medication (Springer, 2014). The choice between daily oral pills or intramuscular injections should be made with your patient.

Acamprosate

Acamprosate is an appropriate treatment option if your patient cannot take or is not interested in naltrexone. Discuss up front that this medication consists of two pills three times per day, which is challenging for medication adherence. Reduce the dose by ½ in patients with moderate CKD and do not prescribe if GFR is less than 30. The dosing for this medication is 666 mg TID, or 333 mg TID for patients with moderate CKD. The number needed to treat for acamprosate is 20 to reduce the likelihood of a return to any drinking (Jonas 2014).

Disulfiram

The third FDA-approved medication for AUD is disulfiram. This medication inhibits the metabolism of alcohol, causing a systemic build-up of acetaldehyde. Any exposure to alcohol while taking this medication makes a patient uncomfortably ill, with common symptoms including flushing, sweating, headache, nausea, and vomiting; this is extremely important to counsel patients about upfront. Accordingly, this medication is only appropriate if a patient’s goal is complete abstinence and works best if another person can make sure that a patient is taking this medication daily or even administer it directly to the patient. Contraindications include active alcohol use, cardiac disease, pregnancy, and psychosis, and caution should be used in patients with cirrhosis, diabetes, epilepsy, or hypothyroidism. Be aware that disulfiram interacts with many prescription drugs.

Patients may find this patient information page helpful.

Two off-label, non-FDA-approved medications (Gabapentin and Topiramate) also have some evidence for reducing alcohol use.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin treats alcohol withdrawal symptoms and can be used to bridge withdrawal management to maintenance therapy. Studies of gabapentin for AUD used doses of 600 mg BID or TID (Mason 2014, Anton 2020). Small studies estimated that NNT was 5 to reduce heavy drinking days and 6 for abstinence (Anton 2020). Common side effects include dizziness and lethargy, and it carries a potential for misuse. It requires dose adjustment in the case of renal impairment. Generally, as with gabapentin therapy for other indications, it is titrated over days-weeks to reach at least the 600 mg TID dose. A small study supports that using gabapentin in combination with naltrexone (Anton, 2011) may lead to improved drinking outcomes, in Dr. Cohen’s expert opinion he will use these medications together, but further research is needed to draw firm conclusions.

Topiramate

Topiramate has shown comparable efficacy in reducing heavy drinking compared to naltrexone and acamprosate (Muller, 2014). This anticonvulsant acts on the gabaergic system. The dose requires gradual up-titration; Dr. Peterkin recommends starting with 25mg-50mg daily and titrating weekly by 25- 50 mg to a total daily dose of 300 mg. Daily doses of >50 mg should be divided into two. Patients often have difficulty tolerating this medication due to significant side effects, including dizziness, weight loss, depression, and mental slowing. Renal dose adjustment is required for a creatinine clearance of <70. Studies suggest possible efficacy for using topiramate in cocaine use disorder, so patients who use cocaine may experience additional benefits (Chan, 2019).

Further considerations and follow up

Patients often experience a wide range of symptoms as they decrease their alcohol use, including insomnia and anxiety. Ask patients about these symptoms, discuss the expected trajectory, and treat them as needed.

Follow up

Dr. Peterkin recommends close follow-up (e.g., one month) when patients are getting oriented to treatment. It is essential to be explicit that you are there to support the patient as they navigate recovery. If patients return and state that the AUD medication “is not working,” explore their expectations, what their drinking has looked like since starting medication, and what psychosocial factors contribute to ongoing use. Did they reduce the amount they were drinking? Did they stop drinking temporarily and then return to use? This is an opportunity to help patients reassess their goals to develop a concrete plan.

Whenever possible, discuss whether patients are interested in additional support, including individual counseling, mutual aid groups, or intensive outpatient programs. Even within one organization (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or SMART Recovery), groups differ significantly from each other – discuss with patients that it will likely take time to find a group they connect with. Some evidence suggests that AA increases abstinence rates for people who stay engaged with it, but it is not adequate for everyone (Kelly, 2020). SMART recovery is structured similarly but does not include a spiritual component.

There are no specific recommendations regarding laboratory follow-up for any of these medications, but assess patient risk factors on an ongoing basis – specifically, signs of worsening liver disease for naltrexone and signs of kidney disease for acamprosate. Counsel patients on how to handle medication management if they continue to drink or resume alcohol consumption. For example patients on – naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin and topiramate, should continue the medication even if they continue to drink. Alcohol use is contraindicated for anyone taking disulfiram.

Duration of treatment

Patients can safely take all of the medications above for as long as they need to, barring the development of new contraindications. If a patient expresses interest in discontinuing pharmacotherapy, discuss why they want to stop and how they feel in their recovery. Have they addressed the underlying factors that contributed to their unhealthy use? What are their current goals? The decision to stop is always up to the patient – you are there to support them and continue to follow up.

Co-occurring disorders

Patients with AUD frequently have co-occurring psychiatric disorders. It is essential to connect patients with behavioral health services for further assessment if they are interested, although available services look different in every health system.

Harm reduction for alcohol use

It is vital to discuss harm reduction strategies for alcohol use with your patients based on how and where they drink. Common methods include avoiding shots, consuming food with alcohol, and hydrating between drinks. Identify specific behaviors that increase a patient’s risk of adverse outcomes and plan around those behaviors, e.g. planning rides in advance, partnering with a friend for accountability to keep track of alcohol intake. The University of Washington compiled a one-pager of these and other strategies.