Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ ECG Cases 57 Art of Occlusion MI Part 5 – Clinical-ECG-POCUS Triptych. Written by Jesse McLaren; Peer Reviewed and edited by Anton Helman. August 2025

All that follows is from the above resource.

In this ECG Cases blog we look at combining clinical assessment, ECG and POCUS to identify acute coronary occlusion

Six patients presented with potential ischemic symptoms. Can you use the triptych of clinical, ECG and POCUS to identify which had acute coronary occlusion?

Case 1: 50 year old sudden severe chest pain, brought by EMS as code STEMI. Serial ECG unchanged. No regional wall motion abnormality on POCUS.

Case 2: 40 year old with three days of pleuritic chest pain. Normal POCUS

Case 3: 45 year old previously healthy with 2 hours of chest pain radiating to the left arm. POCUS showed inferior regional wall motion abnormality

Case 4: 70 year old, previously healthy, with 2 hours of chest pain and shortness of breath. Old then new ECG. POCUS showed anterior regional wall motion abnormality

Case 5: 90 year old, history of anterior MI, with weakness and fall. Old and new ECG. POCUS showed anterior regional wall motion abnormality

Case 6: 40 year old with 2 hours of ongoing chest pain radiating to the arm, associated with diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, refractory to aspirin and nitro. Serial ECG unchanged. POCUS showed lateral regional wall motion abnormality

The triptych of clinical, ECG, and POCUS

Let’s put the art in heart! This is the fifth and final blog post of this series looking at the Art of Occlusion MI: how we can use visual concepts to identify acute coronary occlusion on ECG, and how art helps explains the science of OMI. Previous posts looked at mirror image, scale vs proportionality, the overall impression, and sequence photography. All these focused on the ECG, but this post will look at how this fits with the rest of our clinical assessment in the triptych of clinical, ECG and POCUS.

A triptych (from the Greek “three-layered”) is artwork that is divided into three panels, which tells a story—and you need all the panels for a complete picture. Similarly, our assessment of patients with acute coronary occlusion in the emergency department include three inter-related layers of assessment: the first is the clinical picture which starts the story, the second is the ECG which shows signs of occlusion or reperfusion, and third is POCUS for corresponding regional wall motion abnormalities.

The STEMI paradigm is defined and named after one part of one panel – ST segment elevation on the ECG. Any ACS that doesn’t meet STEMI criteria is called “non-STEMI”, which is like throwing away the whole painting if one panel doesn’t meet certain criteria. Even when the ECG does meet STEMI criteria, there’s a risk for delayed reperfusion if the first panel does not tell the story of classic chest pain.

The OMI paradigm is not defined or named after any one panel, but looks at all panels together to tell the story. Each is an incomplete representation, and each view has its advantages/limitations, so they complement each other:

1. Clinical: the history/physical determines the pre-test likelihood for ACS. The higher the pre-test likelihood, the more important are subtle ECG signs of occlusion and corresponding regional wall motion abnormality on POCUS. But a clinical focus on ischemic chest pain will miss patients with anginal equivalents, which can be identified by ECG/POCUS.

2. ECG: interpretation for OMI is important to identify false positive STEMI (ST elevation without OMI) and false negative STEMI (subtle OMI without ST elevation). But even in the eyes of experts or AI, the ECG is only 80% sensitive for OMI. So a clinical picture of high likelihood ACS with refractory ischemia or hemodynamic/electrical instability is an indication for emergent angiography regardless of the ECG.

3. POCUS: If clinical and ECG pictures are already diagnostic of OMI then POCUS does not change the reperfusion decision, and POCUS findings can be subtle or old. But if ECG signs of OMI are subtle then POCUS findings of regional wall motion abnormalities that can complete the picture.

Back to the cases

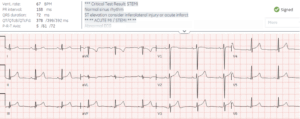

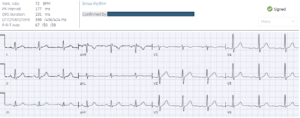

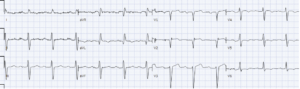

Case 1: 50 year old sudden severe chest pain, brought by EMS as code STEMI. Serial ECG unchanged. No regional wall motion abnormality on POCUS.

- Heart rate/rhythm: normal sinus

- Electrical conduction: normal intervals

- Axis: normal

- R-wave progression: normal

- T: tall

- S: proportional ST/T

= Concerning story but normal serial ECG and POCUS. Code STEMI cancelled and patient sent to ED to look for alternate causes of chest pain: CT showed aortic dissection.

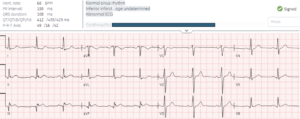

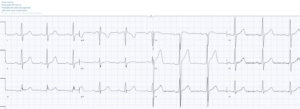

Case 2: 40 year old with three days of pleuritic chest pain. Normal POCUS

- Heart rate/rhythm: normal

- Electrical conduction: normal

- Axis: normal

- R-wave progression: normal

- T: normal

- S: all T waves are asymmetric and pointy, not hyperacute; there is minimal inferolateral concave STE with J waves, with a mirror image in aVL

= atypical chest pain with false positive STEMI which led to cath lab activation and normal coronaries. Serial ECGs were unchanged, serial troponin and Dimer were negative, and echo was normal without pericardial effusion, and patient discharged

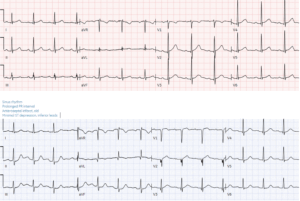

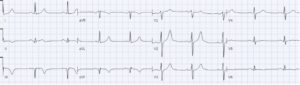

Case 3: 45 year old previously healthy with 2 hours of chest pain radiating to the left arm. POCUS showed inferior regional wall motion abnormality

- Heart rate/rhythm: normal

- Electrical conduction: normal

- Axis: normal

- R-wave progression: normal

- T: normal

- S: primary ischemic STD in I/aVL reciprocal to subtle inferior STE and hyperacute T waves

= typical story with subtle inferior OMI on ECG and corresponding POCUS. Cath lab activated: 100% RCA occlusion. First trop 70 and peak 50,000 ng/L. Discharge ECG showed infero-posterior reperfusion TWI

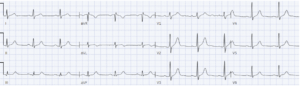

Case 4: 70 year old, previously healthy, with 2 hours of chest pain and shortness of breath. Old then new ECG. POCUS showed anterior regional wall motion abnormality

- H: normal sinus

- E: normal conduction

- A: normal axis

- R: acute loss of R waves V2-4

- T: normal voltages

- S: subtle ST elevation 1-2 with reciprocal STD in V6, and aVL with reciprocal STD inferior

= STEMI negative but typical story with ECG showing subtle proximal LAD occlusion. Stat cardiology consult: bedside echo showed corresponding anterior regional wall motion abnormality. Cath lab activated: 100% proximal LAD occlusion, first troponin 100ng/L and peak 130,000 ng/L. Discharge ECG showed antero-lateral reperfusion TWI.

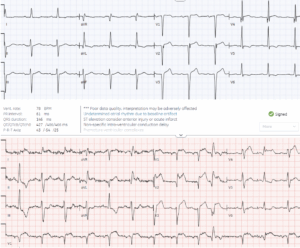

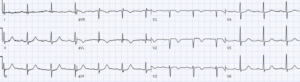

Case 5: 90 year old, history of anterior MI, with weakness and fall. Old and new ECG. POCUS showed anterior regional wall motion abnormality

- H: sinus with PVC

- E: normal intervals

- A: intermittent left axis from LAFB

- R: old anterior Q

- T: normal voltages

- S: new primary STE and and hyperacute T waves anterior (with reciprocal STD V6) and lateral (with reciprocal STD inferior). Also excessive STE seen in the PVC.

= atypical story (with anginal equivalents common in the elderly) but ECG diagnostic of proximal LAD occlusion. Cardiology consult: because of prior MI and lack of current chest pain, all the ECG changes and anterior akinesis on bedside echo were attributed to old anterior MI, and when the first troponin returned at 65ng/L the patient was admitted as ‘non-STEMI’. But troponin rose to a peak of 165,000 ng/L, a massive anterior MI from a missed LAD occlusion. Follow up ECG showed normalization of ST segments, further loss of R wave compared with baseline ECG.

Case 6: 40 year old with 2 hours of ongoing chest pain radiating to the arm, associated with diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, refractory to aspirin and nitro. Serial ECG unchanged. POCUS showed lateral regional wall motion abnormality

- H: normal

- E: normal

- A: normal

- R: normal

- T: normal

- S: normal

Classic story with normal ECG but refractory ischemia. Pain continued despite iv nitro and bedside echo showed inferolateral hypokinesis, so cath lab activated: 99% circumflex occlusion, peak troponin 30,000 ng/L. Discharge ECG showed early R wave progression (mirror to posterior Q) and subtle reperfusion TWI in aVL

Take home points on the Clinical-ECG-PoCUS Tryptych for Occlusion MI

- Clinical: classic symptoms of ACS raise the pre-test likelihood (and refractory or unstable ACS requires angiography regardless of the ECG), but anginal equivalents can be missed

- ECG: signs of OMI can help identify false positive STEMI and false negative STEMI, but the ECG can still miss OMI

- PoCUS: corresponding regional wall motion abnormalities can complement subtle ECG signs of OMI, but PoCUS findings can be missed or can be old

For more see ECG Cases 49: ECG and POCUS for dyspnea and chest pain