Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Psychiatric Research’s Ketogenic Diet Intervention on Metabolic and Psychiatric Health in Bipolar and Schizophrenia: A Pilot Trial [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Psychiatry Res. 2024 May:335:115866. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115866. Epub 2024 Mar 20.

There are 98 similar articles in PubMed.

The above article has been cited 54 times in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Outline

- Highlights

- Abstract

- Keywords

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methods

- 3. Results

- 4. Discussion

- CRediT authorship contribution statement

- Declaration of competing interest

- Acknowledgements

- Funding Disclosure

- Appendix. Supplementary materials

- References

Highlights

- Ketogenic diet therapy resulted in metabolic syndrome reversal in this cohort of serious mental illness.

- Participants with schizophrenia showed an average of 32 % improvement according to the brief psychiatric rating scale.

- The percentage of participants with bipolar who showed >1 point improvement in clinical global impression was 69 %.

- Greater biomarker benefits observed with ketogenic dietary adherence.

- Pilot trial suggests dual metabolic–psychiatric benefits from ketogenic therapy.

Abstract

The ketogenic diet (KD, also known as metabolic therapy) has been successful in the treatment of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and epilepsy. More recently, this treatment has shown promise in the treatment of psychiatric illness. We conducted a 4–month pilot study to investigate the effects of a KD on individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with existing metabolic abnormalities. Twenty–three participants were enrolled in a single–arm trial. Results showcased improvements in metabolic health, with no participants meeting metabolic syndrome criteria by study conclusion. Adherent individuals experienced significant reduction in weight (12 %), BMI (12 %), waist circumference (13 %), and visceral adipose tissue (36 %). Observed biomarker enhancements in this population include a 27 % decrease in HOMA–IR, and a 25 % drop in triglyceride levels. In psychiatric measurements, participants with schizophrenia showed a 32 % reduction in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Overall Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity improved by an average of 31 %, and the proportion of participants that started with elevated symptomatology improved at least 1–point on CGI (79 %). Psychiatric outcomes across the cohort encompassed increased life satisfaction (17 %) and enhanced sleep quality (19 %). This pilot trial underscores the potential advantages of adjunctive ketogenic dietary treatment in individuals grappling with serious mental illness.Keywords

Bipolar illnessSchizoaffective disorderKetogenic diet metabolic therapyInsulin resistanceObesityMetabolic psychiatryMetabolic syndromePsychiatric diseaseClinical trialMental health1. Introduction

Globally, a significant number of people suffer from severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia (24 million) and bipolar disorder (50 million) (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators., 2022). Although there are currently life–saving evidence–based standard therapeutic options for care, many individuals can experience treatment resistance, or major metabolic side effects, which can result in nonadherence of prescribed treatments (Pillinger et al., 2020). Furthermore, traditional neuroleptic medications can increase acute mortality and reduce life expectancy in vulnerable populations, such as those with dementia (Schneider–Thoma et al., 2018). Meta–analyses do show a beneficial effect on long–term mortality in schizophrenia with neuroleptics, however they may have a negative impact on life expectancy due to metabolic effects. The life expectancy gap between schizophrenia and the general population is growing (Jia et al., 2022). If treatment existed that would alleviate the undesirable metabolic effects of the medication, but kept the beneficial neuroprotective effect of neuroleptics through myelination and brain–derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Bartzokis et al., 2002), that would lead to an improved situation for those afflicted with serious mental illness. For these reasons, it is crucial to explore novel treatment approaches to mental illnesses, with the goal of reducing the burden of side effects including metabolic dysfunction.The KD is a therapeutic approach used in the treatment of epilepsy, especially in medication–resistant cases (Liu et al., 2018; Martin–McGill et al., 2020). This approach involves reducing carbohydrate intake and reducing dependence on glucose, resulting in the production of ketone bodies, from fat sources. Ketone bodies can serve as an alternative fuel source for the brain, reducing neuronal excitability and seizure frequency (Rho, 2017). The classical ketogenic diet adheres to a 4:1 ketogenic ratio, meaning the weight of fat is four times that of the combined protein and carbohydrate. This ratio is maintained through the omission of high–carbohydrate items such as starchy fruits, vegetables, bread, pasta, grains, and sugar, while simultaneously elevating the intake of high–fat foods such as nuts, cream, and butter (Freeman et al., 2007). Alternative versions of the KD include a modified ketogenic diet or a well formulated ketogenic diet, which can be easier for adherence compared to the classical version as they more closely resemble the macronutrient ratio of the common western diet (Kossoff et al., 2020). While exact outcomes vary among patients, numerous studies have shown significant seizure reduction or even complete seizure cessation in a substantial percentage of individuals following a well–formulated KD. The diet’s effectiveness is particularly noteworthy in pediatric epilepsy, with multiple reports of patients achieving long–term seizure freedom (Kossoff et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2018; Manral et al., 2023; Martin–McGill et al., 2020; Rezaei et al., 2019; Rogovik and Goldman, 2010; Williams and Cervenka, 2017). Overall, the ketogenic diet remains a valuable and well–established non–pharmacological treatment option for epilepsy.Recent findings support the idea that psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia and bipolar illness, may have underpinnings in metabolic dysfunction, including cerebral glucose hypometabolism, oxidative stress, as well as mitochondrial and neurotransmitter dysfunction, which have downstream effects on synapse connection and neuronal excitability (Brietzke et al., 2018; Coello et al., 2019; Düking et al., 2022; Henkel et al., 2022; Norwitz et al., 2020). Brain metabolism deficits are seen in major mental illnesses (Altar et al., 2005; Andreazza et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2014; Clay et al., 2011; Henkel et al., 2022; Kato, 2017; Mcewen, 2004; Morris et al., 2017). Developing strategies that target this energy dysfunction may lead to treatment options that improve the psychiatric symptoms of these diseases without causing the side effects that are observed in conventional treatment with neuroleptics. A KD provides alternative fuel to the brain aside from glucose and is believed to contain beneficial neuroprotective effects, including stabilization of brain networks, and reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (Düking et al., 2022; Lopresti and Jacka, 2015; McDonald and Cervenka, 2018; Mujica–Parodi et al., 2020; Sethi and Ford, 2022).Adults with mental illness represent a high–risk, marginalized group in the current metabolic and obesity epidemic (Mansur et al., 2015). Among US adults with severe mental illness, metabolic syndrome is a highly prevalent condition that has severe consequences (Penninx and Lange, 2018), with patients estimated to die on average 10–25 years earlier than the general population, largely of premature cardiovascular disease (Laursen, 2011). Notably, patients with major mental illness have an elevated risk of type 2 diabetes (Hajek et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2019), with more than half of those with bipolar disorder experiencing glucose metabolism issues (Calkin et al., 2015; Cuperfain et al., 2020; Hajek et al., 2014; Łojko et al., 2019; Mansur et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2011). Insulin resistance has also been linked to major depressive disorder and schizophrenia (Kullmann et al., 2016; Nasca et al., 2021; Perry et al., 2021, 2016; Watson et al., 2021a, 2021b), contributing to cognitive impairment and potentially influencing treatment resistance (Calkin et al., 2022; Mansur et al., 2021; Watson et al., 2021b). The relationship between metabolic dysfunction and psychiatric disease is likely multifactorial. Genetics, lifestyle factors, and medication have all been reported, to impact metabolic dysfunction in these conditions (Castellani et al., 2022; Hiles et al., 2016; Lieberman, 2004.; Pillinger et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2013; Vogelzangs et al., 2014). The mechanisms through which psychotropic drugs affect metabolism and weight gain remain unclear, but they have been linked to an exacerbation of the underlying dysfunction (Ballon et al., 2018). Undesirable side effects of medication, including changes in metabolism and weight, often lead to treatment discontinuation, contributing to high hospitalization and relapse rates. Ketogenic diets have been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with metabolic abnormalities, such as insulin resistance (Athinarayanan et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; Kosinski and Jornayvaz, 2017). This suggests that a ketogenic diet may reduce the metabolic dysfunction associated with neuroleptic treatment of psychiatric diseases.An overlap between the neurochemical underpinnings and biochemical features of some neurological and psychiatric disorders has been reported (Wingo et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2023). While research on KDs for psychiatric illnesses is in its early stages, with only case reports and observational studies being reported to date (Brietzke et al., 2018; Danan et al., 2022; Kosinski and Jornayvaz, 2017; Kraeuter et al., 2020, 2015; McDonald and Cervenka, 2018; Needham et al., 2023; Norwitz et al., 2020; Palmer et al., 2019; Sethi and Ford, 2022, 2022; Yu et al., 2023), the well-established use of KDs in the treatment of neurological conditions suggests that it would be worthy of exploration in the treatment of psychiatric disorders through carefully planned robust clinical trials. Here, we report on a proof of concept study to evaluate the impact of a four–month single arm KD intervention on both metabolic biomarker profile and psychiatric symptoms among 23 outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar illness.2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a nationwide pilot study of a KD therapy for individuals with a DSM V diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to evaluate impact on metabolic and psychiatric health outcomes. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved of this trial, which is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03935854). Participants were identified for recruitment primarily through referrals from treating physicians or responses to ClinicalTrials.gov and they maintained their standard psychiatric treatment during the trial with no restrictions on dose adjustments with their doctor. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18–75 with appropriate mental health diagnoses who were currently taking psychotropic medications, and who were 1) overweight (body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or above) and had gained more than 5 % of body mass while using psychotropic medicines to manage their mental health condition, or 2) with at least one metabolic abnormality, such as insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia, dyslipidemia, or impaired glucose tolerance. Metabolic abnormality was defined as a comprehensive metabolic panel result outside of the therapeutically accepted range (McPherson and Pincus, 2022). Informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants. Conditions that did not allow for an individual to adhere to a diet were excluded, such as acute psychiatric instability (manic episode, active suicidality requiring hospitalization), or conditions that increased medical risk (anorexia, pregnancy, severe renal or hepatic insufficiency) were excluded. Twenty three participants were recruited in this trial. Two participants withdrew from participation prior to study completion. One participant withdrew as they could not adhere to a non-vegetarian diet and one participant withdrew due to relocation. Of the 21 participants that completed the trial, 5 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 16 were diagnosed with bipolar disorder.2.2. Intervention

The structure of the trial is illustrated in Fig. 1. Participants were initially screened for eligibility through assessment of their medical and psychiatric history and previous laboratory tests from their primary doctor. If eligible and consented, we completed a full medical and psychiatric evaluation, a comprehensive fasting blood test, and asked participants to attend a one–hour teaching session on successfully implementing the KD. Participants were provided with educational handouts at each visit and were provided with a set of popular ketogenic cookbooks, a list of resources, recipes, and assigned a personal coach for the remainder of the study. Individuals were required to complete regular visits with the study physician for medical monitoring weekly in month 1, every two weeks in months 2 and 3, and once in month 4 for a total of 10 medical visits over the course of 4 months. Psychiatric assessments were completed at the baseline, at the midpoint of two months after baseline, and at the final visit four months after baseline, by participant reported standardized questionnaires and clinical assessments with a trained study staff psychiatrist, specialized in bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. These evaluations included mood ratings as well as assessment of participants’ overall functioning. Where possible, assessments were also performed by the participant’s primary psychiatrist. In these cases, the presented score is the average of the two ratings. As this is a one–armed study, the assessor was aware of the treatment plan of the participants. Participants could reach out to their health coach as needed, however on average health coaches checked in with participants for 5–10 min per week throughout the study. The primary role of the coaches was to discuss food–related questions to maintain adherence. Formal psychological support was not provided. All participants were taught and instructed to follow a KD, (macronutrient proportion 10 % carbohydrate, 30 % protein, and 60 % fat; at least 5040 kJ). Participants were not instructed to count calories, but to reduce and monitor carbohydrate intake to about 20 g (excluding fiber) per day, eat 1 cup of vegetables per day, 2 cups of salad per day, and were encouraged to drink 8 glasses of water a day. Participants were educated on how to measure blood ketone levels. We monitored participant ketosis with a blood ketone meter at least once a week and assigned each participant as compliant, semi–compliant, or noncompliant based on the percentage of time in nutritional ketosis. We defined an adherent participant as having blood ketone levels between 0.5 – 5 mM for 80 –100 % of times they were measured, semi–adherent for 50 – 79 % of assayed timepoints, and nonadherent as anything less than 50 % of assayed timepoints (Gershuni et al., 2018).Fig. 1. Trial flow diagram. Note: vital signs include body temperature, pulse rate, respiration rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen level, and blood glucose level.2.3. Assessments

We obtained a fasting blood specimen and measured assays of comprehensive metabolic panel, hemoglobin a1c (HbA1c), fatty acid profile, high sensitivity C–reactive protein (hsCRP), homeostatic model for insulin resistance (HOMA–IR) and advanced lipid testing (LDL subfractions, ApoB, Lip (a)) at baseline and final visits. We estimated insulin resistance using (HOMA2–IR) (Wallace et al., 2004). Tests were performed by a commercial CLIA–certified laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ), which was unaware of the study design or assigned conditions. At each in–person visit, participants had their weight, blood pressure, heart rate, waist circumference, blood ketones level, and body composition measurements recorded by a specialized SECA™ machine in our Stanford metabolic psychiatry® research clinic operated by study staff. Body composition measurements include measurements of visceral fat, lean muscle mass, and absolute body fat. If an individual was remote, participating during the COVID–19 pandemic and unable to attend in person, or out of state, participants were provided with a blood pressure monitor and vitals data was largely self–reported by participant at each visit; however visits to a nearby facility with a specialized SECA or Inbody body composition machine were required and vitals, weight, and body composition measurements were completed there during visits 1, 3, 6, 8, and 9. Additional self–reporting on blood ketone levels was requested weekly between visits for all participants with pictures requested for confirmation of ketone levels. Psychiatric measurements gathered at visits 1, 6, and 9 included: Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD–7) (American Psychological Association, 2006), Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ–9) (Kroenke et al., 2001), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989), Clinical Mood Monitoring Forms (CMF) (Sachs et al., 2002), Clinical Global Impression–Schizophrenia (CGI–SCH) Scale (American Psychological Association, 2003), Clinical Global Impression for Bipolar Disorder–Overall Severity (CGI–BP–OS) (Spearing et al., 1997), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Aas, 2011), Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) (Priebe et al., 2012), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) for Schizophrenia (Overall and Gorham, 1988), and screening for suicidality. Medical visits included side effects screening, which was evaluated and specifically asked about at each clinical visit during their appointments.Throughout the duration of the study, a systematic evaluation of potential side effects associated with the KD was conducted during each medical visit, in comparison to those arising from psychiatric medication.2.4. Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using standard statistical analysis methods using Microsoft Excel. Data was recorded within REdCap. Participants’ repeated measures outcomes were done comparing baseline to final measurements. Data was reported as mean (+/- stdev). A paired t–test analysis was done for each participant between baseline and final quantitative data with confidence intervals of p = 0.001** and p = 0.05*, with asterisks noting statistically significant differences. The average difference was calculated, and the individual participant’s values were compared with the average difference to find the squared deviation of the observed change, (d–davg)^2. For each participant, the percent change was the average difference divided by the average initial value. Average percent change of each category (adherent, semi–adherent) was an average of these individual percentages. Using the number of data points available, we calculated the standard deviation of the observed change, and the standard error of the difference (SED). Using the SED and the difference, we calculated t. Using a standard double tailed t chart for n-1 degrees of freedom, the probability of obtaining this result by chance was calculated, and a value of p < 0.05 or lesser probability was considered significant. This analysis was repeated for all participants, adherent participants, and semi adherent participants (Glantz 1997). As this was an exploratory pilot trial, the study was not powered. McNemar’s Test was done for statistical analysis of nominal data, such as the percent of participants recovered, with the Chi–squared analysis done online (GraphPad, 2024) with confidence intervals of p = 0.001** and p = 0.05*, with asterisks noting statistically significant differences. For differences in demographics of adherent versus nonadherent participants, a two–tailed t–test for unequal group sizes was calculated with v = n1+ n2 −2 degrees of freedom. HOMA–IR was calculated as (Fasting insulin, uIU/mL)*(Fasting glucose, mg/dL)/405. Visceral adipose tissue volume (VAT:WC) in liters was reported in standard SECA instrument analysis. Where InBody scan was substituted, it was reported instead as Visceral Fat Area (VFA) and converted to a VAT measurement using a correlation of VAT= 0.0174*VFA + 1.2857 (Hamasaki and Hamasaki, 2018).3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Results are reported on twenty–three participants. The data analysis cohort includes 5 participants with schizophrenia and 16 participants with bipolar illness. Fourteen participants were fully adherent to the diet (defined as above 80 % of ketone measures >0.5), six participants were semi–adherent (defined as ketones >0.5 above 60–80 % of the time), and one participant was non–adherent (defined at as ketone >0.5 < 50 % of the time). See Table 1 for baseline demographic data of participants. See Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for medications participants were on at baseline and observed changes during study.Table 1. Participant demographic and baseline characteristics across all adherence levels.

Baseline Demographics Empty Cell Empty Cell Empty Cell n Cohort Adherent Semi-Adherent (n = 21) (n = 14) (n = 6) Age (years, mean +/- SD) 43.4 +/- 15.6 38.5 +/- 12.7 51.7 +/- 17.9 Diagnosis (%) Bipolar 76.20 % 71.43 % 83.33 % Bipolar I 33.33 % 28.57 % 33.33 % Bipolar 2 42.86 % 42.86 % 50.00 % Schizotype disorders 23.81 % 28.57 % 16.67 % **Schizophrenia 9.52 % 7.14 % 16.67 % **Schizoaffective Disorder 14.29 % 21.43 % 0.00 % Gender (%) Male 33.33 % 35.71 % 33.33 % *Female 61.90 % 57.14 % 66.67 % *Non-binary 4.76 % 7.14 % 0.00 % Race (%) **Caucasian 76.19 % 85.71 % 50.00 % Asian 14.29 % 14.29 % 16.67 % **Other 4.76 % 0.00 % 16.67 % Duration of Illness (years) 16.1 +/- 16.5 11.7 +/- 13.3 25.3 +/- 21.5 History of suicide attempts 38.10 % 35.71 % 50.00 % History of psychiatric hospitalization 71.43 % 64.29 % 83.33 % Co-morbidities > 2** 85.71 % 85.71 % 100.00 % Obesity, BMI>35 42.86 % 42.86 % 50.00 % *Obesity, BMI>30 80.95 % 92.86 % 66.67 % *Hyperlipidemia 66.67 % 64.29 % 83.33 % *Hypercholesterolemia 52.38 % 50.00 % 66.67 % Pre-diabetes 19.05 % 14.29 % 16.67 % **Fatty liver 9.52 % 14.29 % 0.00 % *p < 0.05 **p < 0.001 indicate a significant difference between adherent and semi–adherent groups (by t–test).BMI, body mass index.Baseline demographic data of the cohort includes an average age of 43.4 years old (SD = 15.6), 76 % with bipolar, 24 % with schizophrenia; 33 % male, 62 % female, and 5 % nonbinary. History of suicide attempts were 38 %, and history of hospitalizations was 71 %. Over 85 % of the cohort had more than 2 comorbid medical conditions, including obesity, hyperlipidemia, or pre–diabetes. The participants in this adherent cohort were less likely to have schizophrenia, be on neuroleptics, and have less duration of illness compared with the semi–adherent participants. Semi–adherent participants were more likely to have obesity, abnormal lipid levels, a greater number having more than 2 comorbid conditions, and greater duration of illness. There was no statistical difference in the number of suicide attempts, hospitalizations, or age between these groups.3.2. Metabolic outcomes

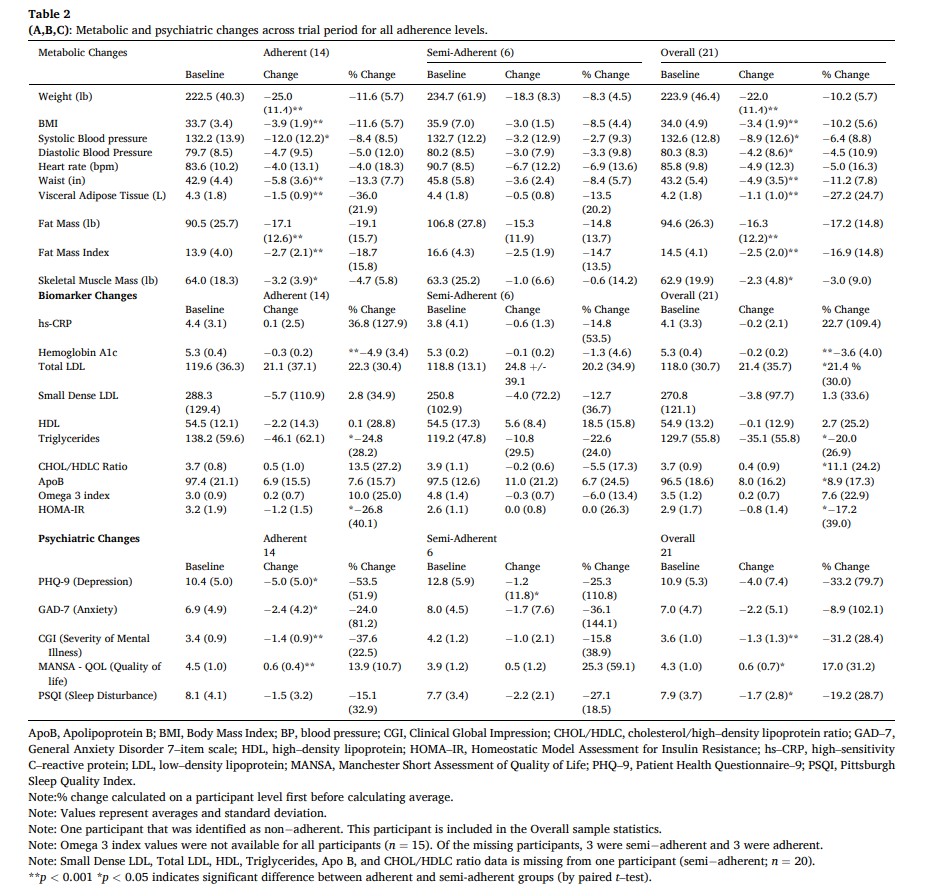

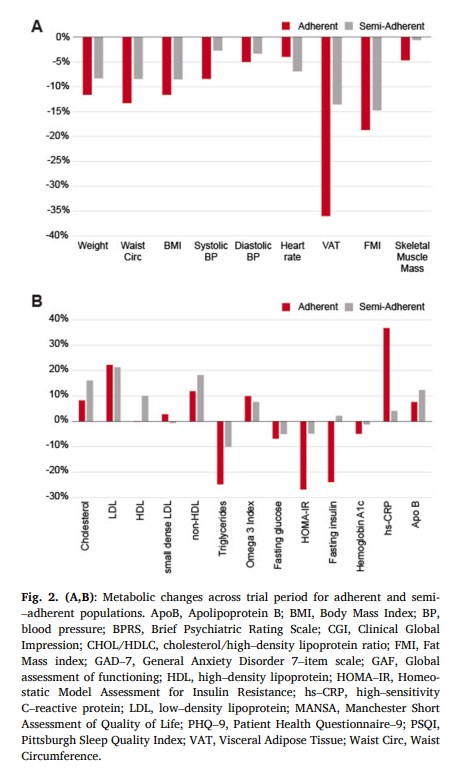

Initially, 29 % of the total cohort met criteria for metabolic syndrome, exhibiting 3 of the following factors: 1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference >40″ in men; >35″ in women) 2) Elevated triglyceride levels (>=150 mg/dL) 3) Low HDL Cholesterol (<40 mg/dL men, <50 mg/dL women) 4) Elevated blood pressure (>= 130/85 mmHg) and 5) Elevated fasting glucose levels (>=110 mg/dL). By the end of the study period, none of the participants met the criteria for metabolic syndrome (p < 0.05). See Table 2 and Fig. 2 for exploratory metabolic marker outcomes separated by adherence (p values are indicated by symbols).Overall, average weight decreased by 10 % (from baseline mean 223.9 +/- 46.4 lb, p < 0.001), waist circumference was reduced by 11 % (baseline 43.2 +/−5.4 in, p < 0.001), systolic blood pressure was reduced by 6.4 % (baseline 132.6 +/- 12.8 mmHg, p < 0.005), fat mass index was decreased by 17 % (baseline 14.5 +/- 4.1, p < 0.001) and BMI was reduced 10 % (from baseline mean 34.0 +/- 4.9, p < 0.001). Metabolic biomarker changes include: visceral adipose tissue reduction of 27 % (from baseline mean 4.2 +/−1.8 L, p < 0.001), a 23 % reduction in hsCRP (from baseline mean 4.1 +/- 3.3 mg/L), a 20 % reduction of triglycerides (baseline mean 129.7 +/−55.8 mg/dL, p < 0.02), an increase in LDL of 21 % (baseline 118.0 +/- 30.7 mg/dL, p < 0.02), an increase in HDL of 2.7 % (baseline 54.9 +/−13.2 mg/dL), and 1.3 % reduction in small dense LDL (baseline mean 270.8 +/−121.1 nmol/L). We observed a 3.6 % reduction in HbA1c (baseline 5.3 +/- 0.4 % of total Hb, p < 0.001) and a 17 % reduction in HOMA-IR (baseline 2.9 +/−1.7, p < 0.05). There was no significant change in the 10-year ASCVD risk score among the whole cohort (−7.9 % change from baseline 3.3 % +/- 4.0 %); however, among adherent participants, there was a statistical improvement of −11 % (baseline 1.4 % +/- 0.5 %, p < 0.01). All individual participant data for LDL, total cholesterol, small dense LDL, triglycerides, visceral adipose tissue, omega 3 index, HOMA–IR, weight, BMI are shown in Supplementary Figures 1–9.3.3. Psychiatric outcomes

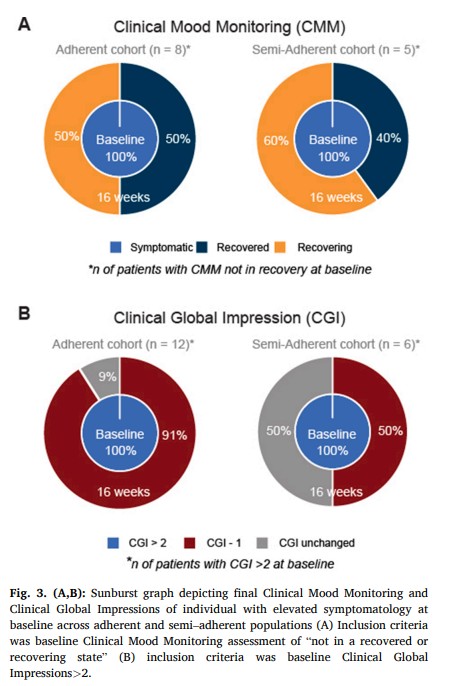

Among the full cohort, Clinical Global Impressions severity of mental illness assessments show average improvement of 31 % (baseline 3.6 +/- 1.0, p < 0.001). The proportion of participants who were in the recovery state at baseline, likely due to neuroleptic medication, as defined by Clinical Mood Monitoring assessments, increased from 33 %, to 75 % by the end of the study. In the adherent group, 100 % were in the recovered state by the end of our study (Fig. 3). Overall, for both bipolar and schizophrenia populations, 43 % (p < 0.02) of participants achieved recovery during the study (50 % for those adherent (p < 0.01), and 33 % for those semi–adherent). In participants with baseline symptoms (of at least mild illness or greater severity), 79 % (p < 0.001) achieved a marked improvement (defined as 1–point CGI change), with 92 % (p < 0.001) for those adherent and 50 % for those who were semi–adherent lmhr.Among bipolar participants only, representing the majority of our cohort, the severity of mental illness (through CGI assessments) showed improvements of >1 point in 69 % of participants, (baseline 3.6 +/- 1.1). The proportion of participants that were in the recovered state (defined by CMF) increased from 38 % at baseline to 81 % at the end of the study. For those participants with bipolar who were in the adherent group, 100 % were in the recovered or recovering state by the end of our study. For these 16 bipolar participants, 6 were initially recovered and 7 recovered by the study end (6 adherent, 2 semi–adherent). Only 3 bipolar participants did not recover as measured by CMF (1 noncompliant, 2 semi–adherent). In bipolar participants with baseline symptoms of at least mild illness or greater severity, 79 % achieved a marked improvement, as defined by 1–point CGI improvement. Among subpopulations according to adherence level, a marked improvement was observed in 88 % of adherent participants and 60 % of semi–adherent participants.3.4. Side effects

Common side effects of a ketogenic diet, including headache, fatigue, and constipation, were documented initially in this study. It is noteworthy that these side effects diminished substantially, reaching minimal to negligible levels beyond the third week of the study (Supplementary Table 3).3.5. Qualitative results

In addition to the metabolic and psychiatric outcomes reported in this study, we wanted to capture direct comments from participants of the study, describing the improvements and the positive impact on their life quality, listed below:

- “Since being on the diet, I haven’t noticed any significant anxiety level or attacks. And I’ve been able to work through basically everything I’ve come across.”

- “It can honestly save a lot of lives, it saved mine. I would not be here today if it wasn’t for Keto. It’s helped a lot with my mood Stabilization.”

- “[…] if things continue in a positive trajectory, it’s definitely not out of the real[m] of possibility that my bipolar could go into remission.”

- “My opportunity to participate in the metabolic psychiatry study transformed my life. I gained knowledge, became able bodied again and my mood disorder and eating disorder symptoms lessened dramatically. I became sexually active again after 16 years of celibacy.”

- “I can tell you that I have never felt better than I have since using ketosis, it worked far better than the lamotrigine ever did.”

4. Discussion

We report on the psychiatric and metabolic outcomes observed in the first cohort of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder undergoing a specific KD treatment intervention adjunctive to psychiatric medication. The psychiatric outcomes indicate that, on average, the severity of mental illness, as assessed by the Clinical Global Impressions scale, improved by 31 %. Furthermore, 79 % of participants with baseline symptoms, experienced clinically meaningful improvement, with higher rates of improvement observed in the adherent group. Baseline symptoms were classified as anyone of elevated symptomatology that was not in “recovery” or “recovering” state according to the defined per Clinical Mood Monitoring definition or a CGI of above 2, as defined by CGI. The study also found improvements in other psychiatric outcomes, including increase in life satisfaction, an enhancement in overall functioning, and improvement in sleep quality. These results suggest that the intervention had a positive impact on mental health and well–being of the participants. A substantial proportion of participants adhered to the treatment, demonstrating the feasibility and possibility of implementation of this regimen in this outpatient population.

The metabolic outcomes presented in this study show improvements in various metabolic biomarkers and overall health parameters. These findings indicate that the intervention had a positive impact on metabolic health. All participants who met criteria for metabolic syndrome experienced its reversal by the end of the four month study. The cohort exhibited a considerable reduction in weight (10 %), waist circumference (11 %), systolic blood pressure (6 %), fat mass index (17 %), and BMI (10 %). Metabolic biomarkers, such as visceral adipose tissue, HbA1c, and triglycerides also demonstrated notable reductions. There was no significant change in the 10–year ASCVD risk score in the overall cohort, however among adherent participants, there was a significant change. The reduction of HbA1c by 3.6 % and HOMA–IR by 17.2 % reflect improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity. These results collectively suggest that the intervention led to beneficial changes in weight, body composition, and metabolic markers, including insulin sensitivity in a metabolically vulnerable population. Although limited data is available, the results suggest a dose–response relationship between ketone level and degree of improvement, suggesting better outcomes at consistent higher ketone levels.