I recently completed the International Trauma Life Support Course (ITLS) at IU Health Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis. It was an excellent course and I believe that any clinician interested in trauma care will benefit from it.

This blog is basically my study notes and my peripheral brain. Placing my notes online makes makes them available to me anywhere. And that is because the excellent built-in search function of the content management software [WordPress] makes it easy to find my notes on any topic when I want to review them.

This post contains excerpts from International Trauma Life Support For Emergency Care Providers Provider Manual, 2016*.

* Here are links to:

Specifically, this post consists of excerpts from Chapter 2, Trauma Assesment And Management, pp 28 – 49.

Here are the excerpts:

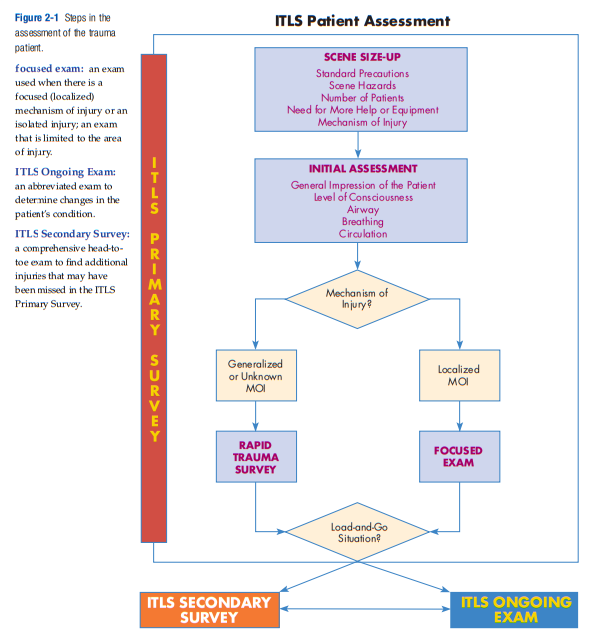

patient assessment:

the process by which the emergency care provide evaluates a trauma patient to determine injuries sustained and the patient’s physiologic

status; made up of the ITLS Primary Survey, ITLS Ongoing Exam, and ITLS Secondary Survey.ITLS Primary Survey:

a brief exam to find immediately life-threatening conditions; made up of the scene size-up, initial assessment, and either the rapid trauma survey or the focused exam.

initial assessment:

a rapid assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation to prioritize the patient and identify immediately life-threatening conditions; part of the ITLS Primary Survey.

rapid trauma survey:

a brief exam from head to toe performed to identify life-threatening injuries.

See When Is A Trauma Patient Load And Go – Help From International Trauma Life Support (ITLS)

Posted on March 20, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

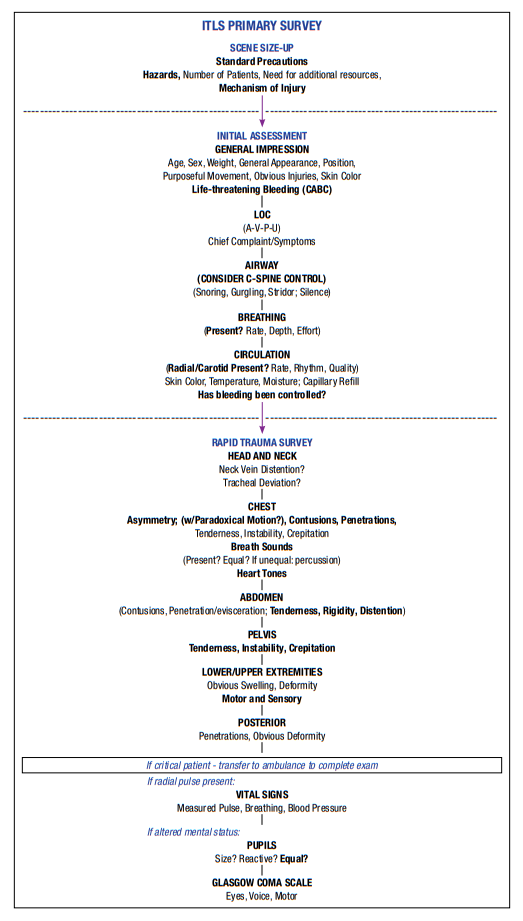

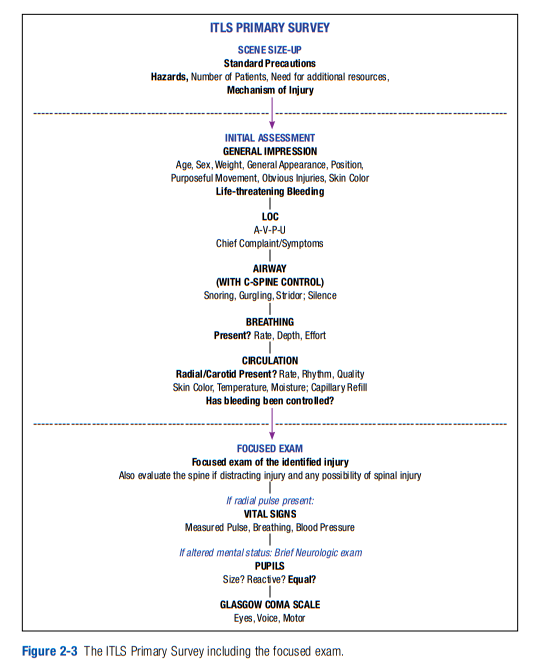

Figure 2-2

The ITLS Primary Survey

including the rapid trauma survey

Scene Size-up

On-scene trauma assessment begins with certain actions that are performed before you approach the patient. It cannot be stressed enough that the failure to perform preliminary actions can jeopardize your life as well as the patient’s life. Perform the

scene size-up as described in Chapter 1.Once you begin your assessment of the critical patient, you may not have time to return to the vehicle for needed equipment. For this reason, always carry essential medical equipment with you to the patient’s side.

Once the scene is safe to enter, as team leader, you must focus your attention on the rapid assessment of your patient. All decisions on treatment require that you have identified life-threatening conditions. Remember, once you begin patient assessment in the ITLS Primary Survey, only four things should cause you to interrupt completion of the assessment. You may interrupt the assessment sequence only if (1) the scene becomes unsafe, (2) you must treat exsanguinating hemorrhage, (3) you must treat an airway obstruction, or (4) you must treat cardiac arrest. (Respiratory arrest, dyspnea, or bleeding management should be delegated to other team members while you continue assessment of the patient.)

Experience has shown that injuries are missed or treatment errors occur because the team leader stops the initial assessment to perform an intervention and forgets to perform part of the assessment. To prevent this, when immediate interventions are

needed, delegate them to your team members while you continue the assessment. This is an important concept that immediately addresses problems encountered and yet does not interrupt the assessment sequence and does not increase scene time. Teamwork is essential to good patient outcomes.As you perform your assessment, you will identify critical interventions that need to be performed immediately. You should instruct the other members of the emergency medical team to carry out these interventions. For example, as you check the airway, another team member can apply a nonrebreather mask at 15 LPM, or prepare to maintain the airway with a BVM or BIAD. When you check the neck, other team members should be applying a cervical collar

Initial Assessment

The initial assessment is made up of your general impression on approaching the patient; an evaluation of the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC); manual spinal motion restriction (if needed); and an assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing,

and circulation (ABCs).Evaluate Initial Level of Consciousness While Obtaining Cervical-Spine Stabilization

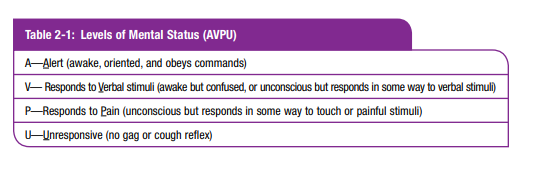

As you approach the patient, identify yourself: “My name is _____. We are here to help you. Can you tell me what happened?” The patient’s reply gives immediate information about both the status of the airway and the LOC. If the patient responds appropriately to questioning, it indicates the airway is open and the LOC is normal. If the response is not appropriate (the patient is unconscious or awake but confused), make a mental note of the LOC using the AVPU scale (Table 2-1).

Anything below “A” (alert) should trigger a systematic search for the causes of the altered mental status during the rapid trauma survey. Loss or decrease in LOC can be caused by many things, including obstructed airway, respiratory failure, shock, and increased intracranial pressure, as well as drugs or metabolic disorders.

The rapid trauma survey leads you in a systematic, organized way to look for the causes of the altered LOC.

Assess the Airway

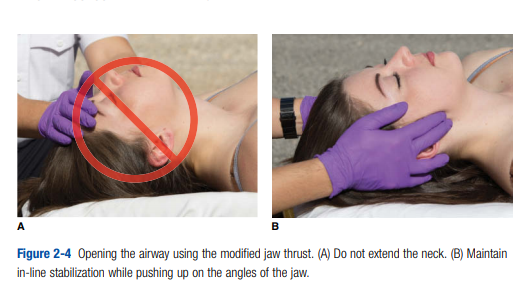

If the patient cannot speak or is unconscious, further evaluation of the airway should follow. Look, listen, and feel for movement of air. Emergency care provider 2 should position the airway as needed. Because of the ever-present danger of spine injury, avoid extending the neck to open the airway of a trauma patient. If the airway is obstructed (apnea, snoring, gurgling, stridor), use an appropriate method (reposition, sweep, suction) to open it immediately (Figure 2-4). Failure to quickly provide

an open airway is one of the four reasons to interrupt the patient assessment part of the ITLS Primary Survey. If simple positioning and suctioning fail to provide an adequate airway, or if the patient has stridor, advanced airway techniques may be

necessary immediately.Assess Breathing

Look, listen, and feel for movement of air. If the patient is unconscious, place your ear over the patient’s mouth so you can judge both the depth (tidal volume; see

If the chest is moving but you do not feel air at the mouth or nose, the patient is not breathing adequately. Notice if the patient uses accessory muscles to breathe. If ventilation is inadequate (Table 2-2),

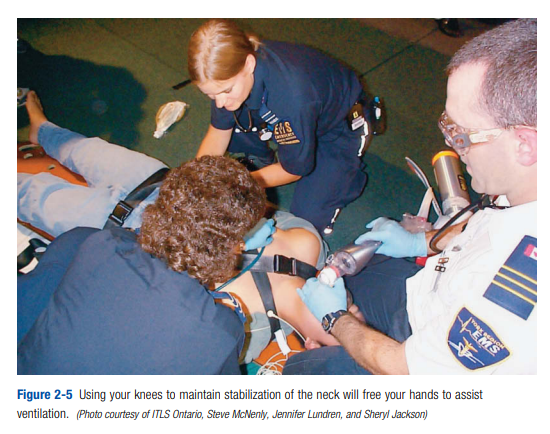

emergency care provider 2 should begin to assist ventilation immediately using his or her knees to restrict movement of the patient’s neck, which will free his hands to apply oxygen or use a bag-valve mask to assist ventilation (Figure 2-5).

When assisting or providing ventilation, be sure that the patient gets an adequate ventilatory rate (one breath every six to eight seconds) and an adequate volume, as evidenced by an adequate chest rise (about 500 mL for an adult or 10 mL/kg for a child).

Emergency care providers tend to ventilate too fast when using a bag-valve mask.Later, when you are able, monitor ventilation with capnography (recommended). You should maintain the end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) at about 35–45 mm Hg. All patients

who are breathing too fast should receive supplemental high flow oxygen. As a general rule, all patients with multiple-system trauma should receive supplemental high-flow oxygen. Several recent studies suggest that too much oxygen may be harmful, so it would be prudent to try to keep the pulse oximeter reading around 95% rather than 100%.Assess Circulation

Start here on p. 36.