In this post I review Dr. Farkas’ IBCC chapter, Acetaminophen Toxicity [Link is to the podcast] [Link is to the show notes].

For me, the eye opener of this IBCC chapter is that half of all acetaminophen toxicity is due to unintentional poisoning*:

*So with that in mind I need to be quick to think of chronic toxicity in patients and to check an acetaminophen level and liver enzymes. And to perhaps start acetylcysteine therapy while awaiting acetaminophen level and liver enzyme results. Of course, I would also be in immediate contact with my poison control center.

For dosing of acetaminophen, please see Acetaminophen-Link To And Excerpts From The IBCC Chapter On Analgesia

Posted on February 24, 2021 by Tom Wade MD

Here are the direct links from the chapter to each section of the chapter:

CONTENTS

- Epidemiology & pharmacokinetics

- Clinical evolution

- Patient evaluation

- Decontamination

- Who needs treatment?

- Acetylcysteine

- Massive acetaminophen poisoning

- Management of established hepatic failure

- Management of renal failure

- Algorithm

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

Here are excerpts:

epidemiology & pharmacokinetics

basics

- Acetaminophen doses above ~8 grams may be toxic, but this varies considerably between patients.1

- Peak absorption of immediate-release tablets usually occurs within 2-4 hours of ingestion.

phenotypes of acetaminophen poisoning

- (1) Suicide attempt (~50%)

- (2) Unintentional poisoning (~50%)

- i) Patients with chronic pain who take acetaminophen along with combination analgesics (e.g. acetaminophen-oxycodone).

- ii) Patients with cold/flu symptoms who take acetaminophen along with combination cold medications (e.g. NyQuil and related products that combine acetaminophen with antihistamines).

- iii) “Alcohol-Tylenol syndrome” – ongoing use of several grams of acetaminophen daily along with alcohol.1

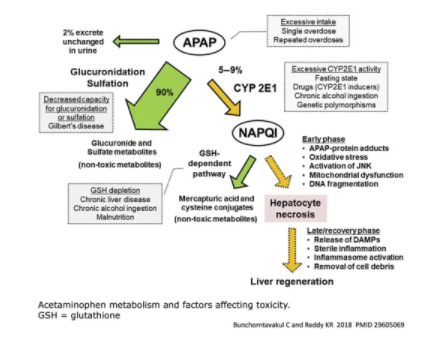

factors that increase the risk of acetaminophen toxicity

- Decreased hepatic capacity for glucoronidation

- Gilbert’s disease

- Zidovudine, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

- Inducers of CYP2E1 (increase metabolism of acetaminophen into toxic NAPQI)

- Isoniazid

- Rifampicin, phenobarbital

- Phenytoin, phenobarbital

- Hepatic depletion of glutathione

- Chronic alcohol ingestion

- Chronic acetaminophen use

- Chronic liver disease

- Malnutrition

clinical evolution

Toxicity is typically divided into stages, but this may not work perfectly in every patient (especially in patients who ingested several doses of acetaminophen over time).

Stage I (0-24 hours) = Incubation

- Asymptomatic or nonspecific symptoms (anorexia, nausea/vomiting, diaphoresis).

- Other symptoms during this period usually suggest coingestion or massive ingestion.

- Massive ingestion (>32 grams) may present with mental status alteration and lactic acidosis within 12 hours of ingestion.2 These patients should be considered for specific treatment as discussed below.

- Labs

- Liver function tests are generally normal (but may begin to rise 8-12 hours after massive ingestion).

Stage II (24-72 hours) = Latent period

- Stage I symptoms resolve or improve.

- Right upper-quadrant pain can occur.

- Labs:

- AST/ALT elevation occurs.

- Nephrotoxicity may occur.

Stage III (72-96 hours) = Peak liver toxicity

- Systemic symptoms re-appear (nausea/vomiting, anorexia, malaise).

- Hepatic failure emerges (encephalopathy, jaundice, coagulopathy, hypoglycemia).

- Greatest risk of death.

- Labs

- Transaminases peak 3-4 days after ingestion

- Hepato-renal syndrome can occur

- INR elevation

- Lactic acidosis*

*Lactic Acidosis from StatPearls [Internet]. Last Update: November 21, 2020.

Stage IV (4 days-2 weeks) = Resolution

- Patients who don’t die make a complete recovery.

patient evaluation

historical elements

- Timing & amount of ingestion

- Single ingestion vs. multiple/chronic ingestions

- History of alcoholism or malnutrition?

- History of known liver disease?

pertinent labs

- Electrolytes & glucose level

- Lactate can be elevated:

- i) Early-onset lactic acidosis following massive ingestion (within 24 hours)

- ii) Later-onset lactic acidosis due to hepatic failure (>48 hours after ingestion)

- Acetaminophen level

- Marked hyperbilirubinemia (>10 mg/dL) may cause a false-positive acetaminophen level, usually in the low range (0-30 ug/ml).1 Bilirubin elevation in this range usually isn’t due to acetaminophen, so other causes of liver injury should be considered.

- INR

- Liver function tests (including ammonia)

- (Additional evaluation for concurrent poisoning with other substances, as clinically warranted)

approach

- This is one approach to acetaminophen intoxication. This strategy places a high priority on not missing cases of acetaminophen injury, and a low priority on avoiding treatment with acetylcysteine.

- For best effect, acetylcysteine should be given within 8 hours of ingestion. If known acetaminophen ingestion occurred >8 hours previously, or if there will be a delay in obtaining acetaminophen levels, it may be safest to start acetylcysteine immediately to avoid treatment delay. You can always stop it later on.

- When in doubt, you’re better off erring on the side of treatment (patients are unreliable, acetylcysteine is safe, and liver failure is bad).

decontamination? [Basically, call and ask the Poison Control Center]

activated charcoal

- Should be considered if patients present shortly following ingestion and are able to protect their airway (<1-3 hours).

- Could provide the greatest benefit to patients with massive acetaminophen poisoning (e.g. >32 grams).3

who needs treatment?

preamble: why the ICU perspective is different

- There are roughly two patient populations with acetaminophen toxicity seen in the ICU:

- (1) Patients with liver failure due to acetaminophen poisoning.

- (2) Patients with polysubstance intoxication admitted to ICU for supportive care, who also happen to have a positive acetaminophen level.

- In general, the main challenge regarding acetaminophen toxicity is determining which patients need to be admitted and which can be discharged home. This issue is irrelevant in the ICU, because a decision has already been made to admit the patient.

- Among patients admitted to the ICU, this shifts the risk/benefit ratio towards treatment for acetaminophen intoxication:

- Risk of treating with acetylcysteine in the ICU is negligible.

- Benefit of treating with acetylcysteine is potentially large (rarely may be life-saving).

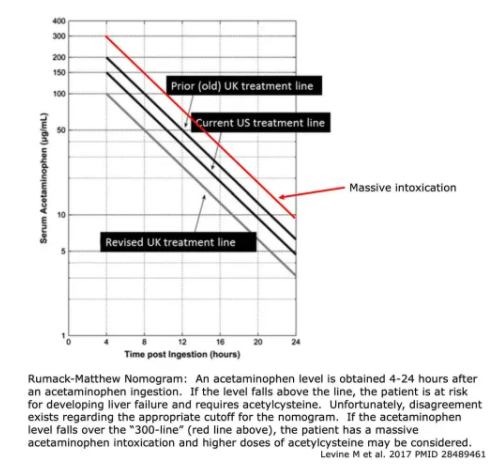

Rumack-Matthew Nomogram

- This predicts the likelihood of hepatic failure based on acetaminophen level following a one-time ingestion.

- Disagreement exists regarding the ideal cutoff used in the nomogram, as shown above.4 To err on the side of caution, it may be safest to use the United Kingdom treatment line.

- Nomogram confounders might cause the nomogram to fail:

- Incorrect history about timing of intoxication.

- Multiple ingestions or chronic acetaminophen use.

- Factors that increase the risk of acetaminophen toxicity:

- Chronic alcoholism (not acute alcohol intoxication)

- Malnutrition

- Drugs that increase acetaminophen toxicity (INH, rifampin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, zidovudine)

- Altered pharmacokinetics

- Extended-release acetaminophen preparations

- Delayed gastric emptying (e.g. opioids, gastroparesis)

- Ingestion >24 hours before presentation

- Wrong units (make sure your units match the nomogram!)

approach

- This is one approach to acetaminophen intoxication. This strategy places a high priority on not missing cases of acetaminophen injury, and a low priority on avoiding treatment with acetylcysteine.

- For best effect, acetylcysteine should be given within 8 hours of ingestion. If known acetaminophen ingestion occurred >8 hours previously, or if there will be a delay in obtaining acetaminophen levels, it may be safest to start acetylcysteine immediately to avoid treatment delay. You can always stop it later on.

- When in doubt, it’s generally better to err on the side of treatment (patients are unreliable, acetylcysteine is safe, and liver failure is bad).

acetylcysteine

IV acetylcysteine is preferred over oral regimen

- Two options are available: a 24-hour IV regimen and a 72-hour oral regimen.

- The 72-hour oral regimen is a logistical nightmare:

- Oral acetylcysteine smells like rotten eggs and makes patients vomit.

- Patients will often refuse to continue with the regimen at some point.

- The 24-hour IV regimen is generally used:

- Extremely safe.

- Faster & logistically easier than the oral regimen.

- It rarely can cause an anaphylactoid reaction, with histamine release due to direct action of the medication. However, this isn’t a major problem (more on this below).

- Dosing regimen

- Can be calculated here (although many hospitals will have a computerized protocol for this as well).

- 1st infusion = 150 mg/kg over 60 minutes

- 2nd infusion = 50 mg/kg over 4 hours

- 3rd infusion = 100 mg/kg over 16 hours

- For patients with very high levels of acetaminophen (above the 300-line, shown in red above), consider higher doses of acetylcysteine (more on this below).

anaphylactoid reactions from IV acetylcysteine

- Rapid administration of acetylcysteine can cause an anaphylactoid reaction. This involves histamine release due to a direct action of the medication (not an IgE-mediated allergic reaction).

- Anaphylactoid reactions are uncommon (especially if the initial dose is infused more slowly, over 60 minutes). When they do occur, they are usually mild (involving the skin only). They invariably occur within six hours of initiation of acetylcysteine, most often within the first two hours.5

- Treatment may be as follows:

- Only symptom is flushing: continue acetylcysteine, carefully monitor patient.

- Urticaria: IV diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg, consider steroid, continue acetylcysteine.

- Angioedema: IV diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg, steroid, hold acetylcysteine for one hour.

- Respiratory symptoms or hypotension: IV diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg, steroid, hold acetylcysteine for one hour, epinephrine (intramuscular bolus or infusion).

- These reactions are not an allergic reaction. Acetylcysteine can be continued or resumed (perhaps at a lower rate initially). Liver failure has been reported when acetylcysteine was inappropriately stopped due to inappropriate fear of an “allergy.”6 Don’t do this.

- When in doubt, poison control can help provide advice on this (in the United States, 1-800-222-1222).

- Fear of an anaphylactoid reaction shouldn’t limit the use of IV acetylcysteine. These reactions are uncommon, mild, and treatable. In one study involving 6,455 treatment courses of acetylcysteine, it doesn’t seem that there was any serious harm from anaphylactoid reactions (e.g. death).5

when to stop the acetylcysteine

- Continue acetylcysteine infusion if there is evidence of liver injury (e.g., ALT > 80U/L) or persistent acetaminophen (>10 micrograms/ml).7

- Treatment failures have been reported if acetylcysteine was stopped prematurely.

- Continue at the same rate, equal to the rate of the third IV dose in the protocol (100 mg/kg infused over 16 hours – repeatedly).

- It’s controversial whether acetylcysteine should be stopped after 3-5 days (even if transaminases remain elevated). It’s probably OK to discontinue the acetylcysteine once the acetaminophen level is undetectable and the liver is making a robust recovery (transaminases are clearly falling and INR is <2).

pregnancy

- Acetaminophen poses a risk of hepatic failure to both mother and fetus.

- Acetylcysteine is safe and beneficial in pregnancy.

- IV acetylcysteine may be especially preferable because it achieves higher serum drug levels and avoids vomiting (of course, IV acetylcysteine is generally the treatment of choice regardless of pregnancy status). If IV acetylcysteine is unavailable, then oral acetylcysteine may be used.

- In a prospective observational study of pregnant women, delayed treatment with acetylcysteine was associated with increased risk of miscarriage and fetal death.8

There is much more to the IBCC Acetaminophen Toxicity and here are direct links to the following sections in the chapter:

massive acetaminophen poisoning

management of hepatic failure

management of renal failure

algorithm

podcast

Pitfalls

- The Rumack nomogram may fail for a variety of reasons, so be careful when using it.

- IV acetylcysteine has been shown to improve mortality in patients with established liver failure. Even if the patient presents very late, they should still be treated with acetylcysteine.

- When using acetylcysteine to treat a patient with established hepatic injury, continue acetylcysteine as an ongoing infusion until the liver recovers (don’t stop after 24 hours).

- Be aware of the existence of massive acetaminophen poisoning. Patients with extremely high levels may require higher doses of acetylcysteine and even hemodialysis.

- Consider acetaminophen toxicity in patients presenting with hepatic injury or failure. About half of cases are inadvertent, so there may be no obvious history of ingestion.

- When in doubt regarding the need to treat, it’s safest to just give IV acetylcysteine (see tweet below). This allows you to stop agonizing about acetaminophen and focus on other problems the patient may have (e.g., co-ingestants).

Going further:

- Acetaminophen overdose (Chris Nickson, LITFL)

- Acetaminophen toxicity (Dan Quan, EP Monthly)

- Acetaminophen toxicity & management (Maryam Abdrabbo and Cuynthia Santos, emDocs)

- Acetaminophen toxicity (WikiEM)