Note to myself: This is a long article but I didn’t find much practical help for clinicians or patients.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from Assessment of Gastrointestinal Autonomic Dysfunction: Present and Future Perspectives [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 31;10(7):1392. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071392.

The above article has been cited by Quantitative gastrointestinal function and corresponding symptom profiles in autonomic neuropathy.

Langford JS, Tokita E, Martindale C, Millsap L, Hemp J, Pace LA, Cortez MM.

Front Neurol. 2022 Dec 15;13:1027348. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1027348. eCollection 2022.

PMID: 36588909

There are 84 similar articles in PubMed Central.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

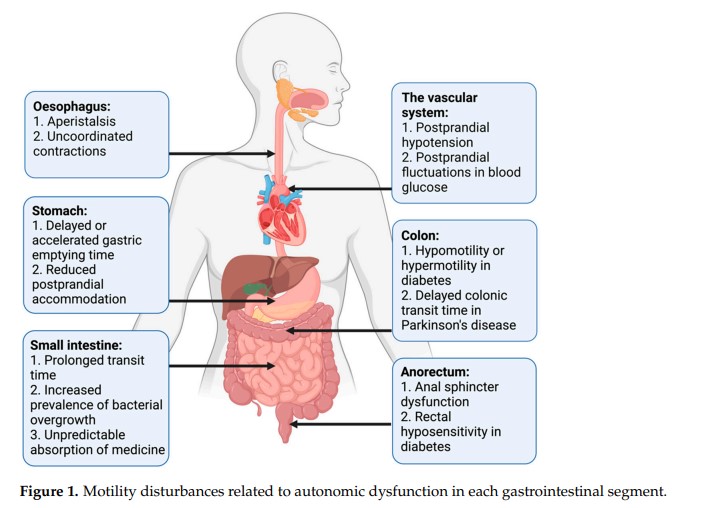

The autonomic nervous system delicately regulates the function of several target organs, including the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, nerve lesions or other nerve pathologies may cause autonomic dysfunction (AD). Some of the most common causes of AD are diabetes mellitus and α-synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease. Widespread dysmotility throughout the gastrointestinal tract is a common finding in AD, but no commercially available method exists for direct verification of enteric dysfunction. Thus, assessing segmental enteric physiological function is recommended to aid diagnostics and guide treatment. Several established assessment methods exist, but disadvantages such as lack of standardization, exposure to radiation, advanced data interpretation, or high cost, limit their utility. Emerging methods, including high-resolution colonic manometry, 3D-transit, advanced imaging methods, analysis of gut biopsies, and microbiota, may all assist in the evaluation of gastroenteropathy related to AD. This review provides an overview of established and emerging assessment methods of physiological function within the gut and assessment methods of autonomic neuropathy outside the gut, especially in regards to clinical performance, strengths, and limitations for each method.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease; autonomic dysfunction; breath test; diabetes mellitus; gastrointestinal; imaging; investigations; manometry; motility.

The underlying pathophysiology of AD varies across patient groups, but assessment methods of the pan-enteric dysfunction are overall identical. Thus, established and emerging methods for assessment of gut function in autonomic disorders and the most relevant general assessment methods of autonomic neuropathy will be reviewed below. The assessment-guided treatment approach will be described at the end of this review.

3. Established Methods for Assessment of Gastroenteropathy

3.1. Exclusion of Differential Diagnoses

When enteric neuropathy is suspected in a patient with an autonomic disorder, the primary approach is to exclude other plausible causes of the gastrointestinal symptoms, such as gastrointestinal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, exocrine pancreas insufficiency, bile acid malabsorption, coeliac disease, and porphyria. Furthermore, it is important to substitute medication if side effects are suspected to be the cause of GI symptoms.

3.2. Assessment of Symptoms

3.3. Tests of Esophageal Motility

3.4. Gastric Emptying Tests

3.5. Assessment of Gastric and Small Intestinal Motility

3.6. Tests of Small Intestinal and Colonic Transit

Assessment of small intestinal or colonic transit times is mainly indicated in patients with abdominal bloating and pain or in patients with symptoms of constipation. It may also be relevant in patients where symptoms of constipation or diarrhea coexist in order to obtain information on the underlying physiology and aid the choice of treatment, see Section 6.

Scintigraphy is established for measuring transit times through the small bowel, colon, and whole gut [75]. The basic principles are similar to those of gastric emptying scintigraphy. However, for small bowel transit time gamma images are continued for 6 h after ingestion, and single images at 24, 48, and 72 h are used to determine colonic transit time [62]. Only a few normative data with a wide normal range are available for small bowel transit time and the interpretation is potentially affected by abnormal gastric or colonic motility. Lack of standardization in clinical practice and time-consuming protocols are drawbacks for intestinal scintigraphy in general [61]. Thus, the method has only gained limited use in AD-related gastroenteropathies [76].

3.7. Assessment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

Patients with intestinal dysmotility, and among these patients with AD-related gastroenteropathy, are predisposed to SIBO [24,87]. The prevalence of SIBO depends on the choice of diagnostic method [32,88]. Assessment of this condition is primarily needed when abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea are present in patients with AD. The most valid method for diagnosing SIBO is a luminal, jejunal aspirate for culture retrieved by endoscopy, but this method is invasive, subject to contamination, and may underestimate the intraluminal amount of microbiota.

In addition to their use for assessment of orocecal transit time, hydrogen and methane breath tests are frequently used as an indirect and non-invasive method to detect SIBO.

Jejunal aspirates for culture did not correlate well with the breath test, and in general methods for diagnosing SIBO lack sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and standardization [90].

3.8. Tests of Anorectal Motility

High-resolution anorectal manometry and high-definition anorectal manometry are increasingly used in clinical practice to evaluate continence and regulation of defecation, primarily in patients with either difficult evacuation of stools or fecal incontinence who do not respond to standard treatment modalities [92].

3.9. Whole Gut Assessment

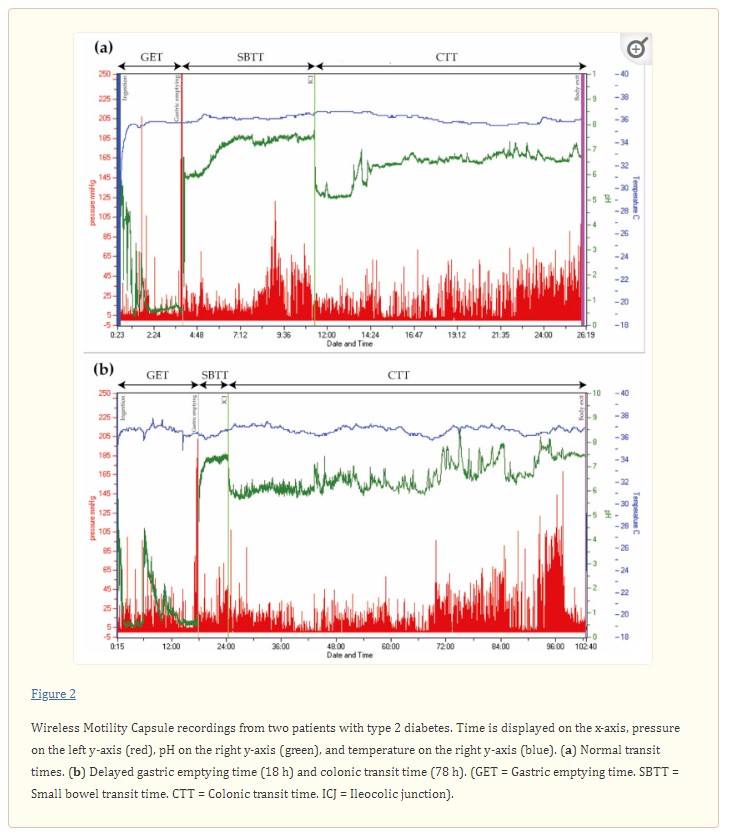

When pan-enteric dysmotility is suspected, often due to combined upper and lower GI symptoms, the Wireless Motility Capsule (Smartpill Monitoring System; Medtronic) is considered the method of choice. An ingested capsule measures pH, intraluminal pressure, and temperature while it passes through the GI tract and transmits this information to a wireless receiver [99]. Accurate measures of the total and regional transit times are provided by using specific pH changes as a surrogate for GI physiological landmarks and temperature to verify expulsion, as seen in Figure 2 [36,99]. The advantages of this test are the availability of substantive normative data and its ambulatory, non-invasive, and radiation-free character [100,101]. Results from the wireless motility capsule correlate with established methods for measuring regional and whole gut transit times [102,103,104].

Evidence suggests multi-segmental dysmotility in the GI system of both patients with POTS and DM, and a recent study showed that test results led to treatment changes in 73% of patients with DM [6,106]. In patients with PD, multi-segmental delayed transit times determined by the wireless motility capsule can also guide treatment [107]. Hence, evaluation of the entire GI tract with only one examination seems like a reasonable choice in AD-related gastroenteropathy [6,36,108].

Pan-enteric assessment methods, such as the wireless motility capsule, are not widely available. Thus, the initial assessment of motility-disturbances is commonly performed by combining a gastric emptying test (for example the gastric emptying scintigraphy), a breath test for SIBO (for example the hydrogen and methane breath tests) and a test of colonic transit time (for example the radio-opaque markers). Furthermore, guided by symptoms and objective motility findings, it may be relevant to perform one of the mentioned manometric investigations. The influence of the assessment methods on management will be reviewed briefly in Section 6.

4. Emerging Methods for Assessment of Gastroenteropathy

The electromagnetic 3D-Transit system (3D-Transit, Motilis Medica SA, Lausanne, Switzerland) is an ambulatory, minimally invasive, and capsule-based technique, which presents similarities to the wireless motility capsule by providing information on regional and whole gut transit times. As the only available technique, the 3D-Transit system can also be used to assess segmental colonic transit times and simultaneously provide a detailed assessment of contraction patterns in a precise anatomical location [109].

The main drawbacks of using this pan-enteric, diagnostic tool is the time-consuming and challenging data analysis, no CE-marking, and no availability outside research settings [112].

4.2. Tests of Colorectal Contractions

High-resolution colonic manometry provides the most precise and detailed description of motor patterns within the colon and has essentially contributed to the understanding of normal colonic physiology [117]. The catheters used are either water-perfused, solid-state, or fiber-optic, with sensors spaced 1–3 cm apart to increase the resolution.

High-resolution colonic manometry is still primarily used for research but is a promising clinical tool for assessment of colonic motor activity, also in patients with gastroenteropathy and AD.

4.3. Imaging

4.3.1. Computed Tomography (CT) In clinical practice, X-ray is the standard test to identify severe fecal retention, but an objective volume estimation technique to be used as a surrogate for the colonic function is lacking. Due to the increased prevalence of constipation in autonomic disorders, combined with alterations in the intestinal tissue, organ sizes may change [5,120,121].

The data analysis in CT-extracted intestinal volumes is time-consuming and currently not applicable in a clinical setting.

4.3.2. Ultrasound Imaging Ultrasound imaging is a useful radiation-free option for showing various diameters of the gut. However, the limitations of ultrasound imaging include difficulty in examining the deep abdominal loops, and a skilled radiologist is needed to obtain a sufficient result [123]. Ultrasound imaging is only sparsely used in gastroenteropathy related to AD [124].

4.3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Visualization of the GI tract with MRI has advanced significantly during the past decade. MRI techniques provide morpho-functional information while being feasible and non-invasive [125,126]

While promising, MRI examinations of GI volumes are not yet used in clinical practice because they are relatively expensive and require highly trained examiners.

4.3.4. 11C-Donepezil Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) 11C-donepezil PET/CT scan visualizes the cholinergic innervation of the GI tract in vivo and may potentially fill the need for a future method to assess the severity of GI autonomic neuropathy [33].

The disadvantages of the method are that it is only performed in very few centers and requires comprehensive data analysis.

4.4. Gut Biopsies

Another way to diagnose GI autonomic neuropathy is to analyze intestinal biopsies. The optimal way to quantify enteric neurons is by obtaining whole-mount preparations to visualize both the submucosal plexus and the myenteric plexus by immunohistochemical neuronal markers [136].

Taken together, several newly established techniques have been developed in which the submucosa and related plexuses are isolated from the mucosa in endoscopically obtained surface biopsies and can be used to evaluate the enteric nervous system in health and disease [143,144]. At present, the methods are almost entirely for research purposes.

4.5. Assessment of the Human Gut Microbiota

Microbiome analysis on the human gut microbiota has significantly improved our knowledge of gut microbiota composition and diversity. An understanding of the human gut microbial diversity in different types of disorders might provide insight into the clinical application in diagnosis and treatments of disease. However, a significant association between microbial patterns and disease initiation or progression has yet to be unveiled.

The above mentioned established and emerging methods for assessment of gut function are summarized in Table 1.

5. Assessment of Autonomic Neuropathy Outside the Gut

Since no commercially available in-vivo diagnostic test of enteric neuropathy exists and the described tests of GI physiological function all have significant limitations, some patients with symptoms of autonomic GI dysfunction may benefit from assessment of extraintestinal autonomic function in support of a diagnosis.

Diagnostic tests of cardiac autonomic neuropathy may serve as a surrogate for autonomic neuropathy within the GI system, but associations between autonomic neuropathy in the two different visceral systems remain incompletely understood.

Cardiac parasympathetic dysfunction can be verified by demonstrating decreased heart rate variability during rest, deep breathing, and the Valsalva maneuver [159]. Heart rate changes to deep breathing are simple to perform and have the highest specificity with vagal afferents and efferents mediating the response [160].

The efferent cardiovascular adrenergic function can be assessed by looking at blood pressure changes during the Valsalva maneuver, during orthostatic stress (active standing or tilt table testing), in response to isometric exercise, and a cold pressor test [161,162,163].

Twenty-four hour blood pressure measurement may detect non-dipping or reverse dipping conditions and postprandial hypotension. The prognostic role of non-dipping and reverse dipping is well-documented, but associations with GI function are unknown [164,165].

Further autonomic testing may be relevant in some patients to recognize AD. A commonly used questionnaire is the COMPASS-31, consisting of 31 questions formed into six symptom domains [38], which may be helpful to screen for AD-related symptoms and add to the assessment of GI autonomic impairment. Autonomic symptoms reflect the organ or function that is affected; however, in general, they are unspecific and will often require objective assessment with various tests [20,166,167,168].

In combination with skin biopsies and quantitative sensory testing, the Q-Sweat contributes to the diagnosis of small-fiber polyneuropathy [14]. Normal values are based on published normative data [160].

With no available standard diagnostic test of pan-enteric autonomic neuropathy, extraintestinal autonomic neuropathy may be used as proxy in clinical practice to verify AD outside the GI tract. However, acknowledgement of subjective GI symptoms and assessment of the physiological function of each GI segment remains the primary focus to aid diagnostics and guide treatment in patients with GI symptoms and suspected AD.

6. Assessment-Guided Treatment

Management of AD-related gastroenteropathy is challenging and treatment response is often unsatisfactory. The poor correlation between GI symptoms and objective findings underlines the need for objective measures to guide treatment.

7. Conclusions

Pan-enteric dysmotility is common in patients with AD despite variation in the underlying pathophysiological changes within the nervous system. With no available standard method for direct assessment of GI autonomic neuropathy, the primary diagnostic approach is physiological, multi-segmental motility testing, and in some patients additional generalized tests of autonomic neuropathy.