Before reviewing Episode 157 [today’s post], first review EMC’s outstanding podcast and show notes, Ep156 ED Approach to Acute Motor Weakness. Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman, voice editing by Raymond Cho, sound design by Yuang Chen. Written Summary and blog post by Priyank Bhatnagar & Saswata Deb, edited by Anton Helman May, 2021.

In this post I link to and excerpt from Ep157 Neuromuscular Disease for Emergency Medicine [Link is to the podcast and show notes] from Emergency Medicine Cases. June, 2021.

Here is the introduction to this podcast, Episode 157:

There is a long list of rare neuromuscular diseases. Nonetheless, there are a few that you are likely to see in the ED, that are relevant to Emergency Medicine because they require timely diagnosis and treatment. In this Part 2 of our 2-part series on acute motor weakness with Roy Baskind and George Porfiris, we keep it short and simple by limiting our discussion to the key clinical clues and management strategies of two of the more common acute life-threatening neuromuscular diseases, myasthenia gravis and Guillain Barré syndrome, and how to distinguish them from their mimics…

All that follows is from the show notes of Ep157 Neuromuscular Disease for Emergency Medicine:

Guillain-Barré syndrome and myasthenia gravis are two neuromuscular disorders that can present with rapid respiratory compromise and subsequent mortality. Fortunately, they both present with hallmarks of clinical diagnosis that the emergency physician can use for early recognition.

Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS): The areflexic ascending symmetric neuromuscular disease

Guillain-Barre syndrome is an autoimmune disorder of the myelin sheath characterized by an acute/subacute onset of progressive peripheral polyneuropathy, symmetrical distribution, ascending pattern of loss of power and areflexia. GBS has a 5% mortality risk, with one-third of patients requiring endotracheal intubation and ICU admission. Even non-ventilated patient can have prolonged admissions of up to 5 weeks. Recovery is also slow, with 50-95% of patients taking a year to return to baseline functional status.

Areflexia and ascending symmetrical weakness are the hallmarks of GBS

The loss of deep tendon reflexes in the patient with acute loss of symmetric ascending motor power should be considered GBS until proven otherwise. It is incumbent upon the EM provider to assess for deep tendon reflexes carefully, employing passive control of the patient’s limb and distraction techniques (such as asking the patient to count backwards from 100 in serial 7s) while eliciting reflexes. With a delay in diagnosis autonomic dysfunction ensues, resulting in swings of tachy/bradycardia and hypo/hypertension as well as diaphragmatic and respiratory muscle weakness and respiratory failure.

Areflexia and ascending symmetrical weakness are the hallmarks of GBS

The loss of deep tendon reflexes in the patient with acute loss of symmetric ascending motor power should be considered GBS until proven otherwise. It is incumbent upon the EM provider to assess for deep tendon reflexes carefully, employing passive control of the patient’s limb and distraction techniques (such as asking the patient to count backwards from 100 in serial 7s) while eliciting reflexes. With a delay in diagnosis autonomic dysfunction ensues, resulting in swings of tachy/bradycardia and hypo/hypertension as well as diaphragmatic and respiratory muscle weakness and respiratory failure.

Preceding viral infections are common in GBS but not necessary for the diagnosis. Up to two-thirds of patient with GBS report preceding viral symptoms. One of the more common viral infections seen in this context is Campylobacter jejuni gastroenteritis.

Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment of GBS is essential to prevent autonomic dysfunction and respiratory compromise

Early treatment of GBS is thought to prevent the progression to autonomic dysfunction and respiratory arrest as well as the need for ICU care/endotracheal intubation. The most effective treatment of GBS is plasma exchange, however it is not readily available at many centers. Hence, IVIG therapy is usually the first line treatment, and if it fails, then plasma exchange is usually initiated.

The two important alternate diagnoses to consider in GBS are tick paralysis and transverse myelitis

Tick Paralysis can be distinguished from GBS by prodromal ataxia, restlessness and irritability, a history of tick bite in an endemic area during spring or summer, and a more rapid progression of disease.

Like GBS, tick paralysis causes an ascending loss of motor power that may lead to respiratory compromise and arrest. It is caused by the salivary neurotoxin of several species of tick. The characteristic prodrome of tick bite paralysis is ataxia associated with restlessness and irritability that begins 4 to 7 days after the tick attaches to the patient’s skin. After these initial symptoms, an ascending, symmetrical flaccid paralysis occurs. This may progress to bulbar involvement and respiratory paralysis. Tick paralysis is more common in children than in adults. Treatment is early removal of the tick and supportive care. It is imperative to consider tick paralysis in the child who presents with ataxia.

Clinical Pearl: In pediatric patients with ataxia and/or acute loss of power and ascending weakness, it is important to thoroughly examine for ticks, including the entire scalp, as this is an often-missed location on assessment. Remove the offending tick using fine forceps applied close to the skin with gentle, steady, upward traction, taking care to avoid leaving tick parts embedded in the wound.

The reason that it is so important to make this diagnosis early and locate the offending tick on the patient, is that simply removing the tick is curative and prevents the progression to respiratory compromise and death.

Distinguishing transverse myelitis from GBS

Transverse myelitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the spinal cord. Like GBS, transverse myelitis is an acquired neuro-immune disorder, often postinfectious, that presents with the acute onset of bilateral lower extremity motor weakness, and may progress to include autonomic dysfunction. However, as opposed to GBS, paresthesias with a distinct sensory level deficit usually accompany the motor weakness, back pain is a typical feature, paresthesias may be asymmetric, reflexes are usually present, and most importantly, as it is a spinal cord condition, transverse myelitis typically presents with accompanying bowel or bladder dysfunction. The usual clinical scenario in the ED that transverse myelitis is considered in is in patients suspected of cauda equina syndrome, and the diagnosis is usually made after MRI, which typically shows 3-5 spinal cord segments of T2 increased signal occupying greater than two-thirds of the cross-sectional area of the cord with a variable pattern of enhancement.

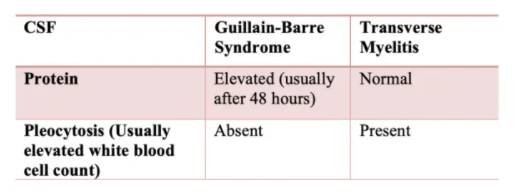

Lumbar puncture may help differentiate GBS from transverse myelitis. Typically, elevated cerebrospinal fluid proteins are seen in GBS, but if done early in the disease course protein levels may be normal requiring a repeat LP later in the hospital stay if GBS remains on the differential. Pleocytosis is typical of transverse myelitis whereas it is absent in GBS.

Recognition and management of respiratory failure associated with neuromuscular disease

Tachypnea and neck flexion weakness are signs of impending respiratory compromise in the patient with neuromuscular disease

Patients with neuromuscular disease are at particularly high risk of respiratory failure, given the propensity for altered mental status and diaphragmatic and/or accessory respiratory muscle weakness. Tachypnea often presents sooner than, and may herald other signs of, impending respiratory failure.

It is prudent for the ED physician to look for the following when assessing the airway status of patient with motor power loss:

- Abnormal or poor mentation

- Difficulty with speech or weak voice

- Drooling or other indication of difficulty handling secretions

- Inability or difficulty lifting their head off the stretcher

- Weak, rapid, or shallow breaths or use of accessory muscles

Pitfall: A common pitfall is to assume that the cause of tachypnea in a patient with suspected neuromuscular disorder with a normal oxygen saturation is due to acidemia only. Tachypnea is often a sign of impending respiratory compromise in these patients due to neuromuscular compromise that may require a definitive airway.

When to intubate the patient with suspected neuromuscular disease: Neck flexor weakness and the “20/30/40 rule”

In addition to tachypnea, impending respiratory compromise can be heralded by decreased neck flexion strength, as it has shared innervation with the diaphragm. This can be tested by resisting neck flexion with your hand against the patient’s forehead and asking them to lift their head off the bed. Normally, the neck flexors are able to overcome the examiner’s hand.

Objective measures that help guide the decision for intubation include:

- Vital capacity (VC) < 20cc/kg,

- Maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP) < 30 cmH2O, and

- Maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) < 40 cmH2O.

The decision to secure the airway should not be made solely on the 20/30/40 rule.

BiPAP or High Flow Nasal Cannulae (HFNC) can be considered as a bridge to a definitive airway or to prevent the need for intubation in those patients with mild symptoms and who pass the 20/30/40 rule.

Myasthenia gravis: the fatigable, fluctuating, descending neuromuscular disease

Start here.