In addition to the resource in this post, please see and review PedsCases‘ Approach to Adnexal Torsion in Children and Adolescents, by Damian.Feldman-Kiss Jul 15, 2021.

From the above resource, the Differential Diagnosis of adnexal torsion [abdominal pain] in an adolescent female always includes:

- ectopic pregnancy,

- ovarian torsion,

- appendicitis,

- ovarian cyst,

- pelvic inflammatory

disease (PID), and- urolithiasis.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from Adnexal Torsion in Adolescents Committee Opinion, Number 783, August 2019 [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF].

All that follows are from the above ACOG opinion:

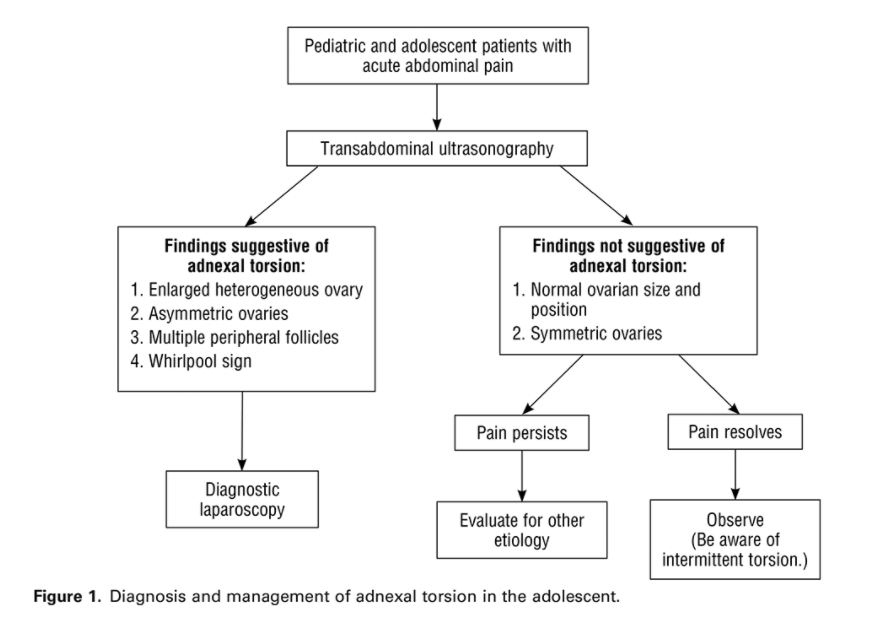

ABSTRACT: Adnexal torsion is the fifth most common gynecologic emergency. The most common ovarian pathologies found in adolescents with adnexal torsion are benign functional ovarian cysts and benign teratomas. Torsion of malignant ovarian masses in this population is rare. In contrast to adnexal torsion in adults, adnexal torsion in pediatric and adolescent females involves an ovary without an associated mass or cyst in as many as 46% of cases. The most common clinical symptom of torsion is sudden-onset abdominal pain that is intermittent, nonradiating, and associated with nausea and vomiting. If ovarian torsion is suspected, timely intervention with diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated to preserve ovarian function and future fertility. When evaluating adolescents with suspected adnexal torsion, an obstetrician–gynecologist or other health care provider should bear in mind that there are no clinical or imaging criteria sufficient to confirm the preoperative diagnosis of adnexal torsion, and Doppler flow alone should not guide clinical decision making. In 50% of cases, adnexal torsion is not found at laparoscopy; however, in most instances, alternative gynecologic pathology is identified and treated. Adnexal torsion is a surgical diagnosis. A minimally invasive surgical approach is recommended with detorsion and preservation of the adnexal structures regardless of the appearance of the ovary. A surgeon should not remove a torsed ovary unless oophorectomy is unavoidable, such as when a severely necrotic ovary falls apart. Although surgical steps may be similar to those taken when treating adult patients, there are technical adaptations and specific challenges when performing gynecologic surgery in adolescents. A conscientious appreciation of the physiologic, anatomic, and surgical characteristics unique to this population is required.

Recommendations and Conclusions

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists makes the following recommendations and conclusions:

- Obstetrician–gynecologists who treat mainly adults are commonly consulted to manage adnexal torsion in an adolescent. Although surgical steps may be similar to those taken when treating adult patients, there are technical adaptations and specific challenges when performing gynecologic surgery in adolescents.

- The most common clinical symptom of torsion is sudden-onset abdominal pain that is intermittent, nonradiating, and associated with nausea and vomiting.

- There are no clinical or imaging criteria sufficient to confirm the preoperative diagnosis of adnexal torsion.

- Doppler flow alone should not guide clinical decision making.

- Although more than one half of cases of pediatric and adolescent adnexal torsion occur in the setting of an adnexal mass, cancer in this age group rarely presents as adnexal torsion.

- If ovarian torsion is suspected, timely intervention with diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated to preserve ovarian function and future fertility.

- A minimally invasive surgical approach is recommended with detorsion and preservation of the adnexal structures regardless of the appearance of the ovary.

- A surgeon should not remove a torsed ovary unless oophorectomy is unavoidable, such as when a severely necrotic ovary falls apart.

- A cystectomy does not need to be performed at the time of detorsion because it may cause additional trauma. If a cystectomy is not performed, a surgeon may consider incision and drainage for large cysts. Ultrasonography to reevaluate the cyst at 6–12 weeks is recommended.

- Adolescents are a unique population with specific needs; thus, special care for placement of ports and lower insufflation pressure may be indicated. Multispecialty collaboration is crucial to optimize care and ensure that minimally invasive detorsion with ovarian preservation is the standard treatment provided to adolescents with adnexal torsion.