In this post I link to and excerpt from Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole [Abilify] for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. VOLUME 386, ISSUE 10011, P2404-2412, DECEMBER 12, 2015.

The above article has been cited by 53 articles in PubMed.

Here is a list of 113 articles similar to the above article in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above article:

Summary

Background

Treatment-resistant major depression is common and potentially life-threatening in elderly people, in whom little is known about the benefits and risks of augmentation pharmacotherapy. We aimed to assess whether aripiprazole is associated with a higher probability of remission than is placebo.Methods

We did a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial at three centres in the USA and Canada to test the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole augmentation for adults aged older than 60 years with treatment-resistant depression (Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS] score of ≥15). Patients who did not achieve remission during a pre-trial with venlafaxine extended-release (150–300 mg/day) were randomly assigned (1:1) to the addition of aripiprazole (target dose 10 mg [maximum 15 mg] daily) daily or placebo for 12 weeks. The computer-generated randomisation was done in blocks and stratified by site. Only the database administrator and research pharmacists had knowledge of treatment assignment. The primary endpoint was remission, defined as an MADRS score of 10 or less (and at least 2 points below the score at the start of the randomised phase) at both of the final two consecutive visits, analysed by intention to treat. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00892047.

Findings

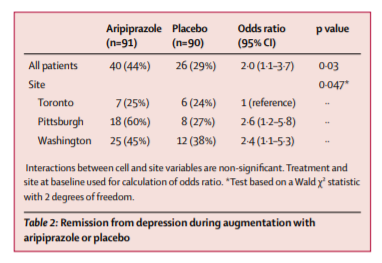

From July 20, 2009, to Dec 30, 2013, we recruited 468 eligible participants, 181 (39%) of whom did not remit and were randomly assigned to aripiprazole (n=91) or placebo (n=90). A greater proportion of participants in the aripiprazole group achieved remission than did those in the placebo group (40 [44%] vs 26 [29%] participants; odds ratio [OR] 2·0 [95% CI 1·1–3·7], p=0·03; number needed to treat [NNT] 6·6 [95% CI 3·5–81·8]). Akathisia was the most common adverse effect of aripiprazole (reported in 24 [26%] of 91 participants on aripiprazole vs 11 [12%] of 90 on placebo). Compared with placebo, aripiprazole was also associated with more Parkinsonism (15 [17%] of 86 vs two [2%] of 81 participants), but not with treatment-emergent suicidal ideation (13 [21%] of 61 vs 19 [29%] of 65 participants) or other measured safety variables.

Interpretation

In adults aged 60 years or older who do not achieve remission from depression with a first-line antidepressant, the addition of aripiprazole is effective in achieving and sustaining remission. Tolerability concerns include the potential for akathisia and Parkinsonism.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder is common in adults aged 60 years and older, leading to disability, suicidality, and increased mortality, but can be mitigated by treatment.1, 2

Most older adults with depression receive treatment in general medical settings, and the geriatric mental health workforce projections show that most older adults with depression will continue to be treated chiefly in the primary care secto3

A major problem is treatment resistance to first-line therapies: 55–81% of older adults with major depressive disorder fail to remit with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).4, 5, 6

Yet, unlike adults aged younger than 60 years,7

little evidence exists from controlled trials to guide second-line or augmentation pharmacotherapy.8, 9

Second-line treatments including mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation with lithium, psychostimulants, or second-generation antipsychotics, interpersonal psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy, have been proposed. Of these treatments, replicated evidence in older adults support only lithium augmentation, which is often difficult to tolerate in this age group.8, 9, 10 Without evidence, clinicians cannot weigh the benefits and risks of these treatments in older adults.11

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov for studies published or underway up until December 2014 that examined augmentation or second-line pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in older adults with the following search terms: “treatment resistance”, “depression”, “elderly”, “augmentation strategy”, “aripiprazole”, and “antidepressant”. The search also used our familiarity with the medical literature and research in progress in the specialty.

As described in two critical reviews of the topic, few trials of any kind and no well powered trials exist to provide evidence for clinicians to make well reasoned decisions about second-line treatment in the common scenario of treatment-resistant late-life depression.

Added value of this study

Our findings bridge a crucial gap by providing clinicians with evidence on the benefits and risks of augmenting antidepressant treatment with an atypical antipsychotic, aripiprazole, in older adults with depression that did not remit with a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Implications of all of the available evidence

About half of older adults with a major depressive disorder do not remit with first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Aripiprazole has a favourable risk–benefit ratio in these older adults, most of whom receive treatment in primary care or general medical settings. The number needed to treat (NNT) with aripiprazole of 6·6 (95% CI 3·5–81·8) is similar to the NNT in young adults of the two most well studied augmentation therapies: lithium (NNT=5) and atypical antipsychotics (NNT=9).

Introduction

Major depressive disorder is common in adults aged 60 years and older, leading to disability, suicidality, and increased mortality, but can be mitigated by treatment.1, 2 Most older adults with depression receive treatment in general medical settings, and the geriatric mental health workforce projections show that most older adults with depression will continue to be treated chiefly in the primary care sector.3 A major problem is treatment resistance to first-line therapies: 55–81% of older adults with major depressive disorder fail to remit with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).4, 5, 6 Yet, unlike adults aged younger than 60 years,7 little evidence exists from controlled trials to guide second-line or augmentation pharmacotherapy.8, 9 Second-line treatments including mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation with lithium, psychostimulants, or second-generation antipsychotics, interpersonal psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy, have been proposed. Of these treatments, replicated evidence in older adults support only lithium augmentation, which is often difficult to tolerate in this age group.8, 9, 10 Without evidence, clinicians cannot weigh the benefits and risks of these treatments in older adults.11

Aripiprazole is a second generation (atypical) antipsychotic drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for augmentation treatment of major depressive disorder. Its pharmacodynamic actions include dopamine D2 and D3 receptor partial agonism and serotonin 5-HT1a and 5-HT2a receptor antagonism.12, 13

However, few data exist to clarify benefits of aripiprazole in older adults with major depressive disorder.15, 16, 17 Additionally, little is known about its safety and tolerability in this age group. This absence of information is worrying because treatment with aripiprazole in younger patients with major depressive disorder is associated with neurological and cardiometabolic adverse effects, particularly akathisia (restlessness) and weight gain.14 Older adults might be more susceptible to such adverse effects.11 Lastly, antipsychotics are associated with increased mortality in older adults with dementia, possibly owing to QTc prolongation, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death.11

Aripiprazole augmentation has potential benefits and risks in the treatment of late-life depression, neither of which is adequately informed by existing data. Accordingly, we did a trial of aripiprazole augmentation in adults aged 60 years or older whose depression did not respond to an adequate trial of venlafaxine. We postulated that aripiprazole would be associated with a higher probability of remission, a greater improvement of depressive symptoms and resolution of suicidal ideation, and a greater stability of remission than placebo. We also hypothesised that use of aripiprazole might lead to an increased risk of akathisia. Finally, we also examined treatment-emergent Parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia, and change in adiposity, weight, lipids, glucose, and QTc.

Methods

Study design and participants

We did a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole augmentation in adults aged 60 years or older whose depression did not respond to an adequate trial of venlafaxine in three academic centres (University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA [coordinating site]; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada; and Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA) after approval by the institutional review boards.

Randomisation and masking

Participants who did not achieve remission with venlafaxine monotherapy were randomly assigned (1:1) to the addition of aripiprazole or placebo while maintaining the final dose of venlafaxine achieved during initial open treatment.

Procedures

In the 12-week randomised phase, aripiprazole or matched placebo tablets were started at 2 mg daily and titrated as tolerated to a target dose of 10 mg daily that could be increased up to 15 mg daily if needed. To assess stability of remission, participants who achieved remission were then followed-up for an additional 12 weeks during which the study drug (aripiprazole or placebo) was continued under double-blind conditions. Adherence was monitored in all phases by self-report and pill counts. Follow-up visits occurred every 1–2 weeks in the first two phases of the study and every 2–4 weeks in the continuation phase. Visits consisted of assessments of depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and medication side effects, and routine management of any participant concerns.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome was remission, defined as completion of the randomised phase with a MADRS score of 10 or less at both of the final two consecutive visits with at least a 2-point drop from the start of the phase. At these visits, the MADRS was measured by an independent assessor. To identify participants who needed a different intervention during the 12-week continuation phase, we ascertained relapse, defined as having enough symptoms to meet criteria for a present major depressive episode.19 We also examined changes in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17-item (Ham-D)20 and both the resolution and the emergence of suicidal ideation using the Scale of Suicidal Ideation.21 Finally, we examined changes in health-related quality of life, using the 36-item Medical Outcome Survey.22

Results

Of 468 eligible participants recruited between July 20, 2009, and Dec 30, 2013, who started venlafaxine extended release, 96 (21%) did not complete the open treatment phase because they withdrew consent, were withdrawn by the investigator, or for other reasons; 191 (41%) participants remitted, 181 (39%) did not remit, 91 were randomised to aripiprazole, and 90 were randomised to placebo (figure 1, table 1).

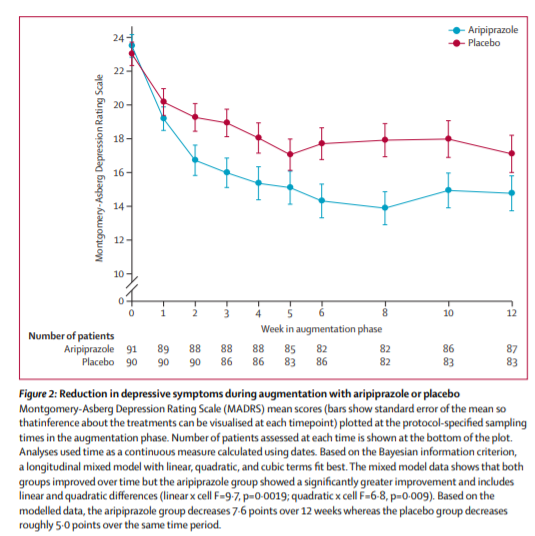

40 (44%) of 91 participants randomly assigned to aripiprazole and 26 (29%) of 90 randomly assigned to placebo achieved remission, a significant difference (table 2). Time to first remission similarly favoured aripiprazole (appendix). The median final aripiprazole dose was 7 mg per day (range 2–15) in remitters and 10 mg per day (range 2–15) in non-remitters (appendix). Participants assigned to aripiprazole had a larger decrease in their MADRS scores (figure 2) and Ham-D scores (appendix) than did those assigned to placebo. The MADRS was measured at each weekly or biweekly visit. We did regular intersite sessions to maintain inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] in this study was 0·997)

Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured at all visits

by study physicians with three validated scales:29

the Barnes Akathisia Scale (outcome:global akathisia

item), the Simpson Angus Scale (treatment-emergent

Parkinsonism defi ned by a 2-point increase in total score),

and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (global

involuntary movements item). Inter-rater agreement for

these scales was adequate to excellent (ICCs range

0·57–0·74) 30 (33%) of 91 participants assigned to

aripiprazole and 25 (28%) of 90 assigned to placebo had

suicidal ideation at baseline, which resolved in 22 (73%)

of 30 participants in the aripiprazole group versus

11 (44%) of 25 in the placebo group (p=0·02).The Medical Outcome Scale (MOS)-Physical Component

Score changed from 42·9 (SD 12·8) to 40·9 (11·3) for

participants in the aripiprazole group, and from 41·6

(11·4) to 41·4 (11·0) for participants in the placebo group

(p=0·15). The participants assigned to aripiprazole had a

greater improvement in the (MOS)-Mental Component

Score than did placebo-treated participants (mean

decrease 6·0; p=0·007).