Here are links to the three Canadian Paediatric Society’s position statements on Autism:

- Early Detection for Autism Spectrum Disorder in Young Children

- Standards of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder

- Post-diagnostic management and follow-up care for autism spectrum disorder

In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Canadian Paediatric Society‘s Standards of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder, Paediatr Child Health 2019 24(7):444–451.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

The rising prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has created a need to expand ASD diagnostic capacity by community-based paediatricians and other primary care providers. Although evidence suggests that some children can be definitively diagnosed by 2 years of age, many are not diagnosed until 4 to 5 years of age. Most clinical guidelines recommend multidisciplinary team involvement in the ASD diagnostic process. Although a maximal wait time of 3 to 6 months has been recommended by three recent ASD guidelines, the time from referral to a team-based ASD diagnostic evaluation commonly takes more than a year in many Canadian communities. More paediatric health care providers should be trained to diagnose less complex cases of ASD. This statement provides community-based paediatric clinicians with recommendations, tools, and resources to perform or assist in the diagnostic evaluation of ASD. It also offers guidance on referral for a comprehensive needs assessment both for treatment and intervention planning, using a flexible, multilevel approach.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder; Diagnostic evaluation; Intervention planning

STEP 1: RECORDS REVIEW

Most diagnosing clinicians begin by reviewing a child’s previous records and interviewing parents and caregivers about their concerns. This process is typically followed by taking a detailed developmental history and scheduling an appointment for direct observation and assessment.

STEP 1: RECORDS REVIEW

Most diagnosing clinicians begin by reviewing a child’s previous records and interviewing parents and caregivers about their concerns. This process is typically followed by taking a detailed developmental history and scheduling an appointment for direct observation and assessment.STEP 2: INTERVIEWING PARENTS, FAMILY MEMBERS, OR OTHER CAREGIVERS

Information is obtained by asking semi-structured, open-ended questions, and may be integrated with information from a standardized questionnaire completed before or during the interview. Topics include:STEP 3: ASSESSMENT FOR CORE FEATURES OF ASD

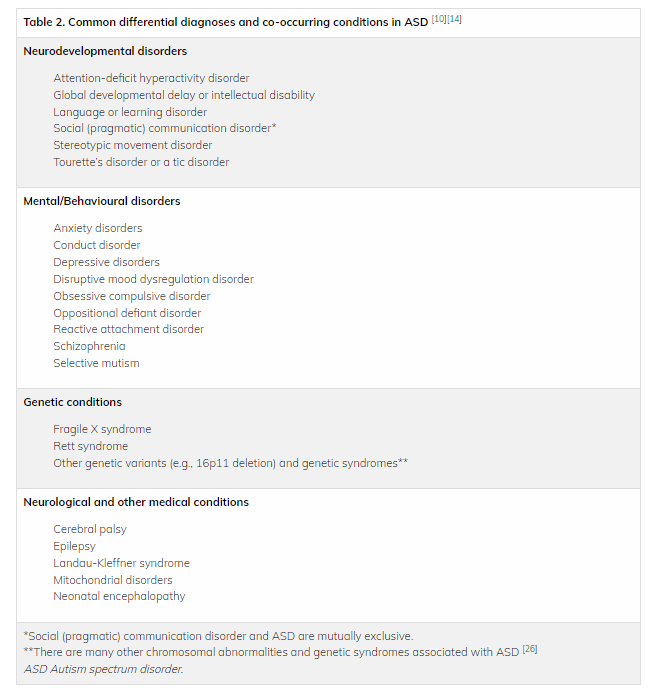

This step involves observing and interacting with the child to assess social interaction and communication abilities. Inquire about or observe for patterns of behaviour or interests, with focus on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD [17]. Behavioural observation in multiple settings is preferred (e.g., clinic, home, or child care), but most assessments occur in clinical settings. An ASD-specific diagnostic tool may also be used.

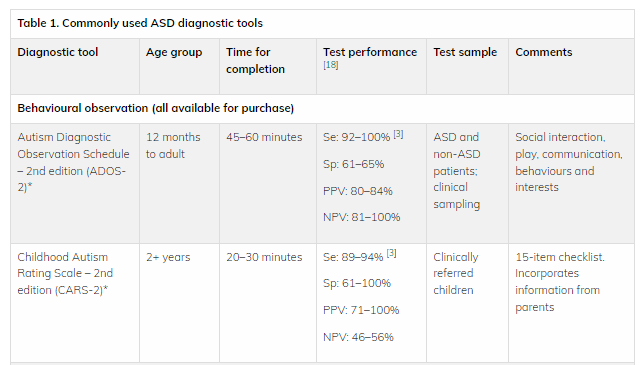

Commonly used ASD-specific diagnostic tools

There are two broad categories of ASD diagnostic tools: those based on coding observations and direct interactions with the child (e.g., ADOS-2, CARS-2) [3][18][21], and those based on parent or caregiver interviews (e.g., ADI-R) or questionnaires (e.g., SRS-2) [3][21][22]. Findings from an ASD diagnostic assessment tool cannot be used alone to diagnose ASD [3]. Rather, results should complement the diagnostic process and inform clinical judgement. Clinically useful ASD diagnostic assessment tools have a sensitivity (i.e., they correctly identify children with ASD) and specificity (i.e., they correctly identify children without ASD) of at least 80%. Common age-specific ASD diagnostic tools are summarized in Table 1 [8][9][14][17]–[20].

The most recent Cochrane review of ASD diagnostic tools for preschoolers found that the ADOS has the highest sensitivity and comparable specificity to the CARS and ADI-R [22]. In some jurisdictions, the ADOS and ADI-R are required to inform ASD diagnosis [2][5].

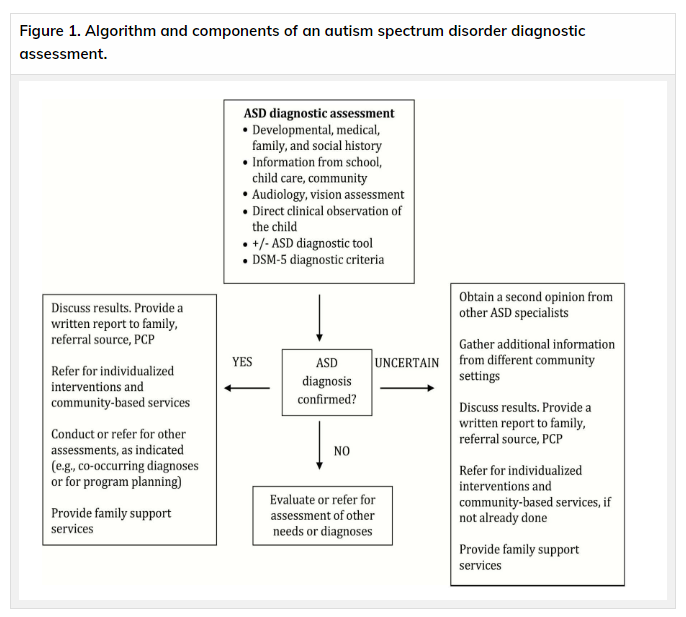

What to do when a categorical ASD diagnosis cannot be determined at the time of assessment.

When a diagnosis is unclear, consider:

- Gathering additional information from other sources.

- Observing the child in a different setting (e.g., home, child care).

- Obtaining a second opinion from a specialized tertiary ASD team.

- Conducting a repeat assessment (e.g., after initiation of therapy or school entry) to clarify potential diagnoses. When children have developmental concerns that do not meet ASD criteria, they should be referred for further assessment and for services that address these concerns.

STEP 8: COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT FOR INTERVENTION PLANNING

After a child has been diagnosed with ASD, the paediatric clinician’s role is to ensure that a comprehensive needs assessment for treatment and intervention planning is considered, when this step was not part of initial diagnostic evaluation. This may involve advocating for further assessment if it appears that a lack of clarity about the child’s functioning may undermine effective planning. This assessment may recur or be revisited at different points throughout child or adolescent development, and in many cases will occur within the context of the child’s educational or treatment program. Understanding overall levels of functioning in several domains, including strengths, skills, challenges, and needs, helps with developing effective, individualized treatment and management planning. Such plans should also consider both individual and family concerns, priorities, and resources. The needs assessment may evaluate:

- Cognitive and academic functioning

- Speech, language, and communication skills

- Sensory and motor functioning, and sensory sensitivities

- Adaptive functioning (e.g., self-help skills)

- Behavioural and emotional functioning (e.g., anxiety, self-esteem issues)

- Physical health and nutrition

The extent of comprehensive assessment for intervention planning is influenced by the approach used for initial ASD diagnostic evaluation.