In this post I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ [Link is to the full episode list] “#230 Kittleson Rules Acute Heart Failure”. By

The Curbsiders remind us to follow Dr. Kittleson on Twitter @MKIttlesonMD

All that follows is from the above outstanding podcast and show notes.

Time Stamps

- 00:00 Sponsor – VCU Health CE; Intro, disclaimer, guest bio

- 02:40 Guest one-liner; Picks of the Week

- 08:33 Case from Kashlak part 1, Definition of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), Factors that lead to ADHF (FAILURE mnemonic)

- 13:39 Historical clues for ADHF; Is salt restriction needed? Fluid restriction?

- 20:42 More on History and Physical exam for ADHF; JVP exam in detail; Crackles are worthless?!

- 28:36 Labs to trend during an ADHF admission

- 33:15 Recap of history, physical exam, and initial approach; Initiating diuresis; Goal urine output; Diuresis in HFrEF vs HFpEF phenotypes

- 45:32 Diuretic resistance and when to use a drip, metolazone; Do K and Mg need to be 4 and 2?

- 49:05 When to hold guideline directed medical therapy (Beta blockers, ARNI, ACEI/ARB)

- 56:05 Who needs a right heart cath?

- 59:30 Endpoints for discharge; Switch to PO diuretics; Approach to discharge and transitions of care

- 64:04 SGLT2i in heart failure

- 68:15 Take home points and outro

- Sponsor – VCU Health CE

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Pearls

- A history of orthopnea and a physical exam showing increased JVP are the cornerstones of diagnosing ADHF. Crackles are not specific (Dr Kittleson doesn’t listen to the lungs!)

- An S3 gallop (“Ken-tu-CKY”) is an extremely specific ADHF exam finding (Drazner et al 2001).

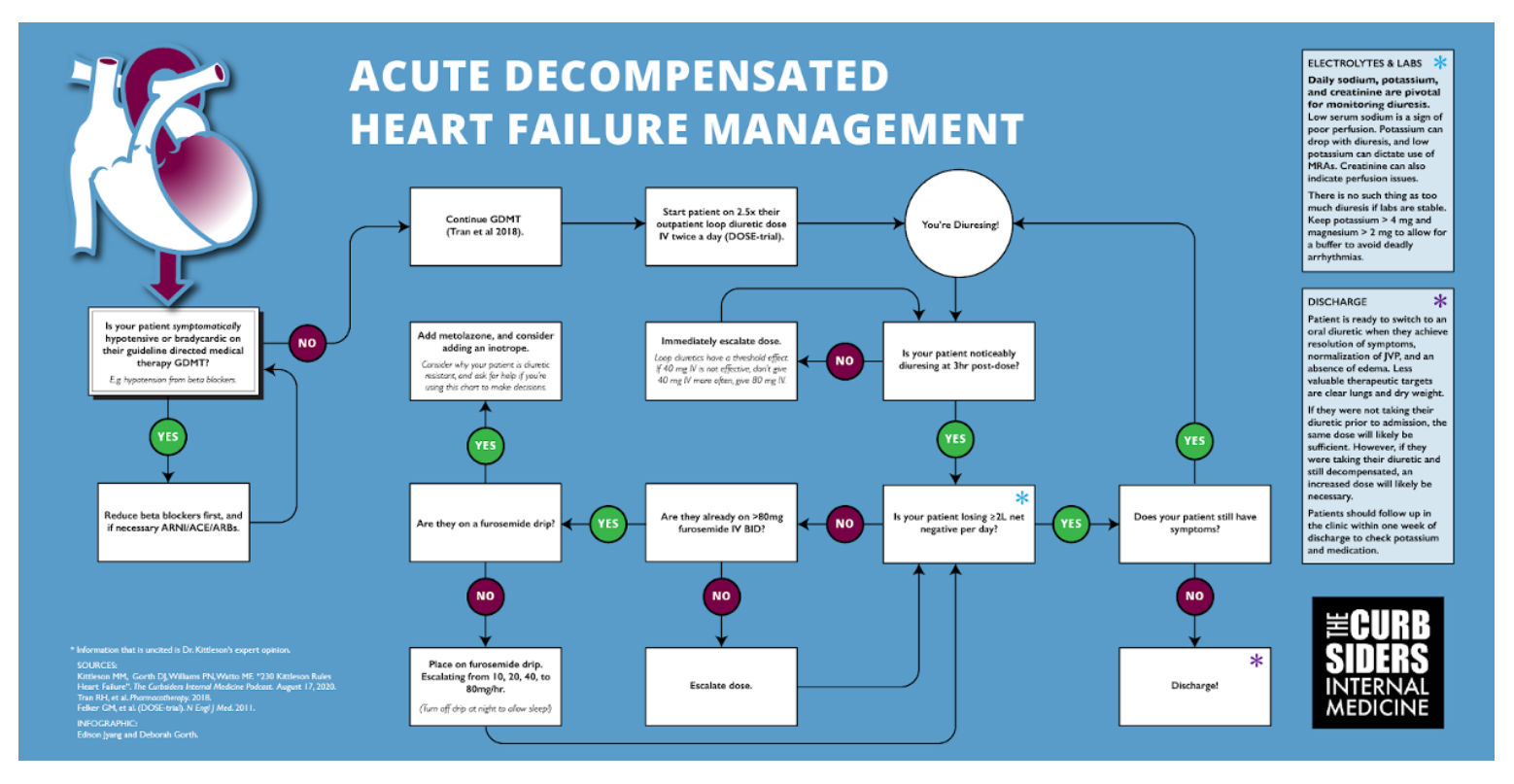

- Continue outpatient ARNI/ARB/ACEi/aldosterone antagonist and beta blocker during diuresis if blood pressure allows (Tran et al 2018).

- Daily goal is 1-2L net negative for HFpEF and at least 2L for HFrEF (“as much as Cr and BP will tolerate). For HFrEF, start diuresis with 2.5x outpatient oral dose given IV twice a day (DOSE-Trial).

- If the diuretic response has not begun within a couple hours, increase the dose immediately instead of waiting until the next scheduled dose.

- Be nice; time diuretic doses and turn off diuretic drips to let your patient sleep.

- Monitor sodium, potassium, and creatinine daily, and replete to K+ > 4 as a buffer (expert opinion).

- Use spironolactone during diuresis to maintain serum potassium.

- Right heart catheters are not therapeutic interventions, but they provide information to help guide therapy.

- Use hospitalizations as an opportunity to optimize guideline directed medical therapy.

- Transition to an oral diuretic dose before discharge that results in 500 cc net negative in 24 hours (expert opinion). Rationale: Patients eat and drink more at home.

To more easily read the flow chart below, please increase the post to 150% in your browser.

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

Renal misinterpretation of decreased cardiac output as volume depletion leads to fluid retention and consequently acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). This volume overload causes pulmonary congestion, abdominal bloating, and gravity dependent edema in the lower extremities or sacral region. While the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) is diverse, the phenomena of ADHF occurs in both HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Although diuresis has not been shown to reduce long term mortality, removing excess fluid is necessary to reverse the pulmonary edema of ADHF that leads to shortness of breath and hypoxia (Ellison and Felker 2017).

*NOTE: The discussion below pertains to HFrEF (ejection fraction <40%).

History Suggestive of ADHF

Asking the correct questions is the key to unlocking an acute heart failure diagnosis. There are innumerable reasons for a patient to be short of breath, but orthopnea, shortness of breath while laying flat, is more specific for ADHF –though the LR is only 2.2 (Wang et al 2005). Uncover a history of orthopnea by asking not just how many pillows your patient uses, but also why your patient is using multiple pillows. Additionally, instead of just asking if a patient ever wakes up in the middle of the night, clarify if when they wake up do they feel short of breath or if waking up was due to other factors. Ask about abdominal bloating and lower extremity edema, patients often know how their ADHF presents.* A history of HF is a great predictor of ADHF (Wang et al 2005).

*Dr. Kittleson reminds us that some patients retain fluid in the abdomen and not in their legs and some patients vice versa.

Understanding the cause of ADHF is an important component of treatment; either you can address the underlying cause of an exacerbation, or an unprovoked decompensation suggests severe disease. It is important to take a history in a non-judgemental manner. Patients may be unaware of the salt content of food that they eat in a restaurant. The FAILURES mnemonic is a great way for remembering the factors that can precipitate ADHF:

Forgetting medication (or taking beta blockers, NSAIDs, methamphetamine, or cocaine)

Arrhythmia or Anemia

Ischemia or Infarction

Lifestyle choices including dietary indiscretions.

Upregulation of cardiac demand from either pregnancy or hyperthyroidism.

Renal failure from progression of kidney disease or insufficient dialysis.

Embolus (pulmonary embolism)

Stenosis from worsening renal artery stenosis, aortic stenosis, or other valvular disease.

SALT AND FLUID RESTRICTION IN ADHF

While the evidence of sodium restriction in hypertension is strong, the role of sodium restriction (2-3 g daily) in HF is less conclusive (HFSA Guidelines 2010). However, it is important to ask your patient what foods, high sodium or high carbohydrate, lead to fluid retention for them. For more information on this topic, our friends at the Core IM podcast have a great episode on salt restriction and HF. A 2 liter fluid restriction is “recommended” by the HFSA Guidelines 2010 for those with severe hyponatremia (sodium <130 mEq/L) and can be “considered” for those with difficult to control fluid retention despite other measures (expert consensus).

Physical Exam for ADHF

The physical exam is crucial to diagnosing ADHF and risk stratifying patients. The two profiles of ADHF are warm-and-wet or cold-and-wet; warm-and-wet refers to well perfused decompensated patients, and cold-and-wet refers to sicker patients who may need inotropic support.

The jugular venous pressure (JVP) is estimated by observing the vertical height of the jugular venous pulse above the sternal angle, >4 cm is considered abnormal. This pulse is the internal jugular vein that can be found in the triangle formed by the sternocleidomastoid and the clavicle. To assess the JVP, recline the patient at 30 or 40 degrees with their head turned gently away from you, so as to not tamponade the vein with muscle or skin tension. Become one with the neck, and observe the biphasic flicker; the a wave corresponds with atrial contraction, and the v wave is from increased venous pressure during filling. If you see a c wave, theoretically formed by the bulging of the tricuspid valve during ventricular contraction, tweet at Dr. Kittleson, and she will be very impressed and/or not believe you. If the JVP is not visible, adjust the angle of the patient to bring it into view. To distinguish between carotid and jugular pulses, press on the belly to see if increased venous return will increase the presumably venous pulsation, or press on the pulsation itself, an arterial pulse will not compress but a venous pressure will. Elevated JVP is 11% sensitive and 97% specific for ADHF, and the addition of checking for the abdominojugular reflux increases sensitivity to 24% (Wang et al 2005).

Listen for an S3 gallop. S3 is 13% sensitive and 99% specific for heart failure; LR = 11; 95% CI, 4.9-25.0 (Wang et al 2005).

While the lung exam is important for assessing other pathologies, listening to the lungs is not an effective way to evaluate ADHF. Crackles alone are not sensitive or specific for ADHF (Wang et al 2005). [#1 thing that irritates Dr. Kittleson: basing a volume assessment on a lung exam]

Dr. Kittleson urges providers to respect sinus tachycardia, because it can indicate that there is a severe underlying condition.

Lastly, bedside ultrasound is an emerging way to augment a ADHF physical exam (Marini et al 2020).

Important Labs for ADHF

Serially checking brain natriuretic protein (BNP) is not useful in managing ADHF (Desai 2013). BNP can be negative in HFpEF or obesity, if it’s high it could be due to renal failure or chronic ventricular dysfunction. [#2 thing that irritates Dr. Kittleson: getting called to the ER for a high BNP without a history or physical exam to accompany it.]

Daily sodium, potassium, and creatinine are pivotal for monitoring diuresis. Low serum sodium is a sign of poor perfusion. Potassium can drop with diuresis, and low potassium can dictate use of MRAs. Creatinine can also indicate perfusion issues.

Initiating Diuresis

The standard of care for diuresis are loop diuretics, which block the Na+-K+-2CL– symporter in the proximal tubule leading to enhanced excretion of water along with these electrolytes. Start dosing with 2.5x outpatient dose IV twice a day (DOSE-Trial). Diurese the patient as quickly as possible, because every day that they spend in the hospital is a chance to get C. Diff. Be nice and consider the timing of diuresis to allow patients to sleep.

Assessing Diuresis

Check the efficacy of dose after the first few hours instead of waiting until the end of the day. If a diuretic is working, the patient will be making an obviously large volume of urine. Loop diuretics have a threshold effect. For example, if 40 mg IV is not effective, don’t give 40 mg IV more often, give 80 mg IV. Aim for a minimum target of 2 liters net negative each day, but there is no such thing as too much diuresis if labs are stable. Consider how much water a patient needs to lose, and set daily goals based on this target. Replete electrolytes as needed; keep the potassium > 4 mg and magnesium > 2 mg to allow for buffer to avoid deadly arrhythmias. Dr. Kittleson suggests that magnesium may be a wonder drug to fix muscle aches from “furosemide-ennui”, and oral magnesium oxide is a low risk intervention.

Escalating Treatment

If 80 mg IV BID is not effective at achieving diuresis goals, consider adding a furosemide drip (escalating from 10, 20, 40, to 80 mg/hr). However, turn the drip off at night (11pm to 5 am, say) to allow the patient to sleep, unless you are a sadist or your patient has a foley. If an 80 mg/hr furosemide drip is not effective, worry and add on metolazone–a thiazide diuretic that inhibits a sodium-chloride symporter in the distal convoluted tubule–for sequential blockade. It is important to figure out why this patient is so diuretic resistant, do they have severe underlying cardiac or kidney issues contributing. If creatinine is less than double baseline, a high creatinine could be a result of venous back pressure due to congestion, and it may resolve with effective diuresis.

You can start (a touch of an) inotrope empirically if creatine is moving in the wrong direction to see if that support augments diuresis. However, a right heart Swan-Gnatz catheter allows you to measure filling pressures, pulmonary artery pressure, and cardiac output. If you have volume overload and renal dysfunction or progresssive hypotension, pulmonary artery catheter can help determine your course of action. Right heart catheters are a diagnostic not a therapeutic intervention. Use diuresis and inotropes to achieve the goals of RA <10 mmHg, wedge <20 mmHg, and cardiac index >2.

Discharge Tips

start here