In addition to today’s resource, please see the following resources for information on encephalitis and autoimmune encephalitis

- Encephalitis from emedicine.medscape.com

Updated: Aug 07, 2018

Author: David S Howes, MD - Encephalitis Clinical Presentation from emedicine.medscape.com

Updated: Aug 07, 2018

Author: David S Howes, MD - Autoimmune encephalitis: proposed best practice recommendations for diagnosis and acute management [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021 Jul;92(7):757-768.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ [Link is to the episode list] #346 Meningitis.* July 25, 2022 By MATTHEW WATTO, MD

*Amin M, Trubitt M, Watto MF, Patel PK. “#347 Meningitis”. The Curbsiders Internal Medicine Podcast. https://thecurbsiders.com/episode-list Final publishing date July 25, 2022

All that follows is from the above resource.

Transcript-The-Curbsiders-346-Meningitis.docx

There’s nothing that gets a hospitalist more anxious and excited at the same time than a case of suspected meningitis. In this episode, we learn that if the thought crosses our mind, a lumbar puncture is almost certainly indicated. Our guest, Dr. Payal Patel, helps us with the balancing act that is diagnosing and managing meningitis!

Meningitis Pearls

- Changes in consciousness and personality are key history points as they can help differentiate meningitis from meningoencephalitis.

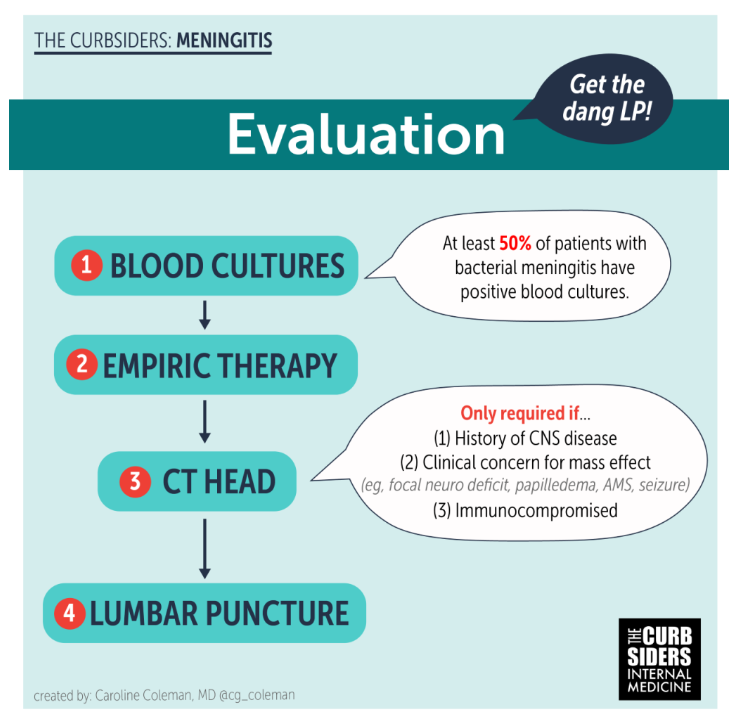

- Lumbar puncture is key in diagnosis and does NOT require a CT Head to perform safely in most cases

- Blood cultures are positive about 50% of the time in bacterial meningitis, so are important to the work-up

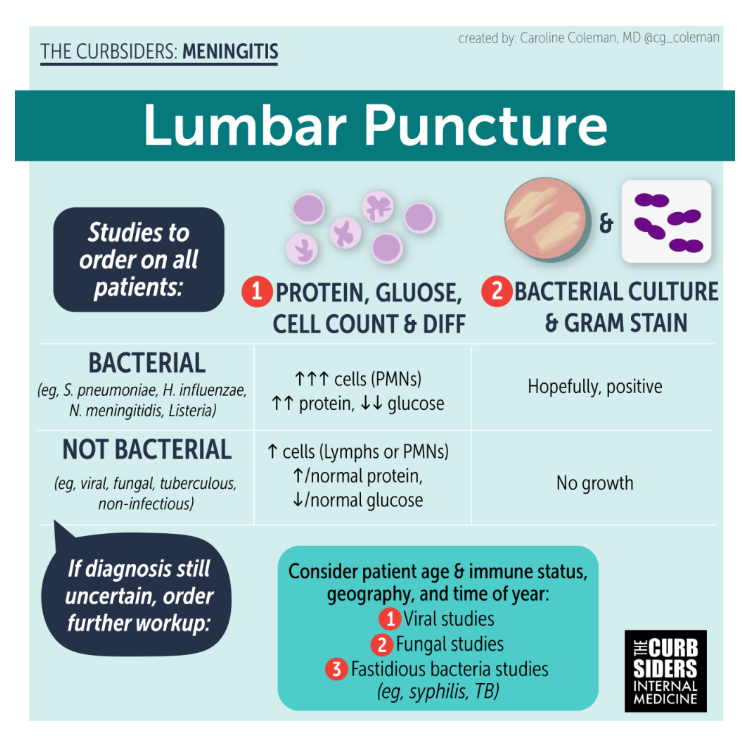

- Cell count and differential of CSF provides the highest-yield clues for diagnosing of bacterial meningitis

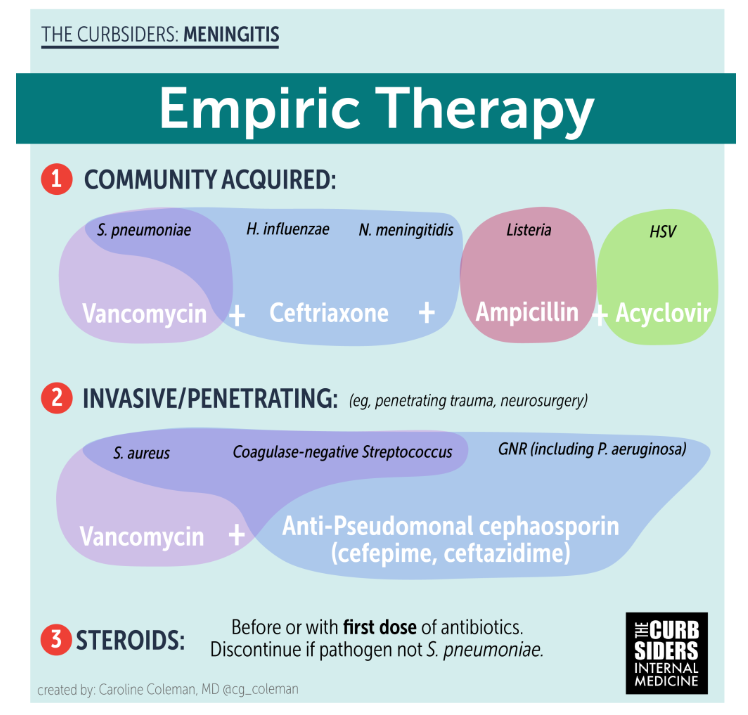

- Empiric coverage for community-acquired bacterial meningitis consists of ceftriaxone and vancomycin

- Ideally, obtain blood cultures and perform lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis before starting antibiotics.

Diagnosis

History and physical

Per Dr. Patel, some keys to differentiate meningitis from meningoencephalitis include personality changes or decreased level of consciousness (i.e. increased sleepiness), recent-onset seizures, or coma, all of which are concerning for encephalitis. On exam, papilledema and focal neurologic findings can also be clues for encephalitis.

Lumbar Puncture and Testing

Diagnosis and management must occur concurrently in cases of possible meningitis in order to provide timely care, though they will be covered separately here.

When meningitis is suspected, lumbar puncture should be performed to obtain cerebrospinal fluid as soon as possible. However, there are some steps that should precede the procedure. Blood cultures should be obtained immediately, as bacteremia often accompanies meningitis. Once these are obtained, empiric therapy (which is addressed later) should be started. A frequent point of confusion is whether a CT head is necessary prior to lumbar puncture. In most cases, it is not required, but there are some instances in which a CT head should be obtained first. These instances include advanced age, prior history of CNS disease (brain metastases), or immunocompromise. A more thorough list of criteria can be found in the IDSA guidelines for meningitis. [Tunkel, et al 2004]

Once CSF is obtained, the bare minimum for testing includes cell count with differential, gram stain with culture, protein, and glucose. The most important thing according to Dr. Patel is the white blood cell count: a normal person would have zero to one WBC. If the number is anything above 5 WBCs, this is concerning for meningitis. If the WBC is very high, the common causes of bacterial meningitis are more likely. As that number decreases, the differential diagnosis becomes broader and includes rare bacterial sources as well as viral etiologies.

While initial testing with cell count and gram stain is key in developing a treatment plan, advanced diagnostics/panel PCR testing can be useful for diagnosing the most common pathogens–Strep, Haemophilus, and Neisseria species, especially in patients who have already received antibiotics. As such, this type of testing can be helpful in determining when to initiate or stop antibiotics. [Tunkel, et al 2004]]

Dr. Patel says that when obtaining CSF, it is important to try to secure more fluid than is required for the initial work-up in case additional studies are needed. When bacterial work-up is negative, Dr. Patel advises testing for other pathogens. These should include fungal and viral studies and sometimes may include universal PCR testing or meta genomic next-generation sequencing. If these tests are also negative, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis should be considered.

Management

The most important thing in management is starting antibiotics ASAP, as delay increases morbidity and mortality. As mentioned above, it is key to obtain blood cultures prior to administering antibiotics[Tunkel, et al 2004].

When selecting empiric coverage, it is important to take into account patient risk factors for specific pathogens (e.g. immunocompromise, advanced age, recent neurosurgery). [Tunkel, et al 2004]

Antibiotics

The guiding principles to choosing antibiotics include determining what the potential causative organisms are for a particular patient as well as accounting for which antibiotics cross the blood-brain barrier. In the case of community acquired infections, an appropriate empiric regimen includes vancomycin and ceftriaxone [Tunkel, et al 2004]. Over time, strep has become resistant to ceftriaxone, hence the recommendation to add vancomycin. If the infection is found to be MSSA, the treatment can be narrowed to nafcillin. Ceftriaxone also covers gram-negative causes as well. [Tunkel, et al 2004]

In older patients (>50 years), the incidence of listeria meningitis is higher and requires ampicillin, as ceftriaxone is not effective against listeria. Notably, listeria is frequently associated with bacteremia. [Tunkel, et al 2004]]

Hospital-acquired infections include MRSA and Pseudomonas spp. Appropriate choices for such infections are vancomycin, cefepime or ceftazidime. [Tunkel, et al 2004]

Steroids

Steroids (traditionally dexamethasone) are helpful in the early stages of strep pneumo meningitis. They should be administered before or with antibiotics. After this initial period, steroids are less not effective. The mechanisms of action of steroids are thought to include decreasing cerebral edema and intracranial pressure, and mitigating other effects of inflammation due to pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [Tunkel, et al 2004]. In high-income countries, steroids are effective at reducing hearing loss and short-term neurologic sequelae when given with or before antibiotics in patients with Strep pneumoniae infections but not Haemophilus or Neisseria infections. In lower-income countries, steroids have not been shown to be beneficial [Brouwer M, et al 2015].

Antivirals

Dr. Patel notes it is okay to start antivirals initially, but once CSF results have returned, use the information to decide whether they are needed. If you have a lymphocytic predominance in the CSF but PCR is negative for HSV, consider a repeat LP if your suspicion is high enough to continue antivirals.

Duration of therapy

Length of treatment is dependent on pathogen as well as presence or absence of bacteremia. Duration in treatment of meningitis is not as well studied, and consulting Infectious Disease is recommended to determine the best course for your patients. For simple, non-bacteremic infections, 10-14 days of antibiotics are appropriate. Regarding steroids, these should be administered for the first four days of treatment of strep infections only. [Tunkel, et al 2004]]

Transitions of Care

Up to 40% of patients can have neurologic sequelae following a course of meningitis, and patients should be counseled on this. These can include hearing loss (though this is more common in children). Mortality in meningitis was as high as 95% before antibiotics. Since the advent of antibiotics, mortality is as low as 7%. Before vaccines, deafness and other neurologic complications were more prevalent. Since the advent of vaccines, these have decreased significantly.