Here is a list of all the types of resources available on PedsCases, Categories.

Today I review PedsCases Approach to Pediatric Vomiting Part 2. I’ve reviewed Approach to Pediatric Vomiting Part 1 previously. Here are the direct links:

- Approach to Pediatric Vomiting (Part 1)

by Erin Boschee Aug 25, 2014- Link to the script [PDF]

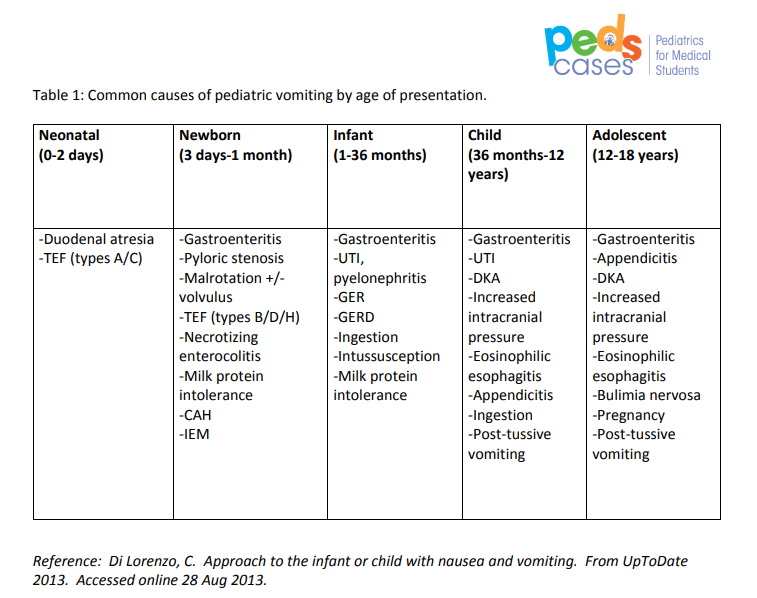

- Link to Table 1: Common causes of pediatric vomiting by age of presentation [PDF]

- Here is the link to my post on Part 1, Links To PedsCases Approach to Pediatric Vomitting Part 1

Posted on May 11, 2020 by Tom Wade MD

- Approach to Pediatric Vomiting (Part 2)

by Erin Boschee Aug 25, 2014

Here are excerpts from Part 2 [Note: be sure and also review my post, Links To PedsCases Approach to Pediatric Vomitting Part 1]:

History

[Determine:]

- the onset,

- frequency,

- time frame,

- provoking and alleviating factors should be explored.

- The vomit should be characterized in detail

including the amount, color, and consistency.First, it should be categorized as bilious or non-bilious.

Second, it should be categorized as bloody or non-bloody.

Third, the vomit should be identified as projectile or non-projectile, as projectile vomiting may point to a specific diagnosis – namely, pyloric stenosis.

Fourth, the age of presentation should be considered.

- In the neonatal period, consider:

- Gastroenteritis

- Malrotation

- Pyloric stenosis

- Tracheo-esophageal fistula

- Necrotizing enterocholitis

- In infancy, common causes to consider include:

- GERD

- Gastroenteritis

- Bowel Obstruction

- Milk protein allergy

- UTI

- In children, one must think of:

- Gastroenteritis

- UTI

- DKA

- Post-tussive vomiting

- Increased intracranial pressure.

- In adolescents, consider:

- Gastroenteritis

- Appendicitis

- DKA

- Increased intracranial pressure

Fifth, one should determine whether the child is febrile or afebrile. The presence of fever increases the likelihood of an infectious etiology.

[Sixth, determine] the presence of any associated GI symptoms

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain

- [Abdominal] distension

- Diarrhea

- Obstipation

[Seventh,] infectious symptoms should be elicited, including:

- Fever,

- Dysuria,

- Ear pain,

- Cough,

- Coryza,

- Shortness of breath

- Meningismus

[Eighth, consider the possibility of diabetic ketoacidosis, DKA:]

- Source: PMID: PMID: 25941653 – The clinical signs of DKA include dehydration (may be difficult to detect), tachycardia, tachypnoea (may be mistaken for pneumonia or asthma), deep sighing (Kussmaul) respiration with a typical smell of ketones in the breath (variously described as the odor of nail polish remover or rotten fruit), nausea, vomiting (may be mistaken for gastroenteritis), abdominal pain (may mimic an acute abdominal condition), confusion, drowsiness, progressive reduction in level of consciousness, and eventually loss of consciousness.

- Review also Diabetic Ketoacidosis – Outstanding Summary And Flow Chart From Emergency Medicine Cases

Posted on April 24, 2020 by Tom Wade MD[Ninth,] Red flag symptoms that you do not want to miss include meningismus, costovertebral tenderness, abdominal pain and any evidence of increased intracranial pressure. Do

not miss a child who is vomiting due to a life-threatening condition such as meningitis, DKA or pyelonephritis.[Tenth,] Increased Intracranial Hypertension [Link is to Download PDF revised 1/15] from Nationwide Children’s Hospital:

Basically if the pediatric vomiting patient has any sign or symptom that could be neurologic, consider Increased Intracranial Pressure.

[This is from the above parent handout. The key is for the pediatrician to look for any of these behaviors in the patient with vomitting. And then to consider Increased Intracranial Pressure as a possible cause.]

- Change in your child’s behavior such as extreme irritability (child is cranky, cannot

be consoled or comforted)- Increased sleepiness (does not act as usual when

you offer a favorite toy, or is difficult to wake up)- Shrill or high-pitched cry

- Nausea (child feels like throwing up)

- Vomiting (throwing up)

- Complaint of a headache or stiff neck

when waking up- Complaint of nausea or throwing up in

the morning- Convulsions (seizures)

- Weakness of one side of the body

- Trouble walking or uncoordinated movement

(staggering or swaying)- Eye changes (crossed eyes, droopy eyelids, blurred or double vision, trouble using eyes,

unequal size of eye pupils, or continuous downward gaze)- Increased head size, if your child is younger than 18 months

- Full or tight fontanel (soft spot), if your child is younger than 18 months

- Loss of consciousness (does not awaken when you touch and talk to him)

- Child just does not “look right” to you

[Eleventh,] assess the patient’s hydration status and ask about:

- Oral intake

- Urine output

- Tear production

- Weight changes.

Finally, it is very important to elucidate the child’s hydration status, so one should always ask about oral intake, urine output, tear production and weight changes

Physical Exam

As with any physical exam, begin with an assessment of the patient’s vital signs and

ask yourself, is this child well or unwell? The initial management and investigations of a stable versus unstable child can be quite different.The physical exam should then begin with an assessment of hydration status. The examiner should assess the fontanelles, skin turgor, mucous membranes, and look for objective measures of stool and urine output. A thorough abdominal exam should be performed looking for abdominal distension, masses or visible peristalsis on inspection. Auscultation should be done to look for

hyperactive or absent bowel sounds. Palpation should assess for tenderness, though this is difficult to assess in infants and younger children, and feel for masses or organomegaly. In older children, special tests to assess for appendicitis or cholecystitis can be performed.A neurological exam should also be done to rule out signs of increased intracranial pressure. This should include assessment for papilledema, bulging fontanelles and the presence of focal neurological signs. A full neurological examination should be done including the cranial nerves, focusing especially on cranial nerve VI, which is typically

the first affected to due its long intracranial course.Examination for evidence of infection is also important and should include inspection

of the tympanic membranes and pharynx, auscultation of the chest and assessment for

meningismus.Lastly, particularly in neonates and infants, the presence of dysmorphic features, ambiguous genitalia or unusual odours should be noted as they may point to an underlying congenital or metabolic cause.

Investigations

Investigations should be based on the history and age of the patient. For instance, a three-month old with vomiting, fever and lethargy is at a high risk of sepsis, so this child should receive a full septic work-up including blood cultures, urine cultures and a

lumbar puncture. An older child with a history clearly suggestive of gastroenteritis who

does not appear unwell will likely not require any investigations.Standard investigations might begin with a CBC with differential, electrolytes, creatinine,

urea, glucose, liver function tests, and urinalysis with culture and sensitivities to rule out systemic infectious or common endocrine causes. In the presence of bloody diarrhea or history of recent travel, stools should be sent for culture and sensitivity.Abdominal imaging can be very useful to identify the cause of GI-associated vomiting.

An abdominal flat plate can assess for bowel obstruction through the presence of air

fluid levels and bowel distension. A CT scan of the abdomen or upper GI series with

contrast can be used to further identify the location of the obstruction or anatomical

abnormality. Abdominal ultrasound is the modality of choice to assess for suspected

pyloric stenosis.