This podcast and these show notes are outstanding reviews. They are worth frequent review.

Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ “Ep 212 PECARN Febrile Young Infant Prediction Tool: When To Safely Forgo LP and Empiric Antibiotics“.*

*Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Burstein, B. Kuppermann, N. Episode 212 PECARN Febrile Young Infant Prediction Tool: When To Safely Forgo LP and Empiric Antibiotics. Emergency Medicine Cases. January, 2026. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/febrile-infant-pecarn-prediction-tool. Accessed February 2, 2026

All that follows is from the above resource.

If you’ve been practicing EM for more than a decade, your approach to the febrile young infant has (appropriately) evolved. For years, the default was LP + empiric antibiotics + admission for almost everyone. That approach prevented missing meningitis, but at the cost of a lot of harm: invasive testing, unnecessary antibiotics, and hospitalization-related complications. The modern approach is a paradigm shift toward risk stratification, biomarkers, and shared decision-making, while still respecting one immutable truth: Missing neonatal bacterial meningitis can be catastrophic. This episode revisits the framework from a prior EM Cases episode and updates it with a landmark study that directly informs how far we can safely go—especially in the 0–28 day group, with the father of multiple well-known PECARN rules Dr. Nathan Kuppermann and lead author Dr. Brett Burstein…

Click this link to play the podcast. Download (Duration: 47:36 — 43.6MB)

Febrile young infants and the paradigm shift in workup and management

Historically, most febrile young infants were managed with a one-size-fits-all approach that included a routine lumbar puncture, empiric antibiotics, and hospital admission. While this strategy reduced the risk of missing bacterial meningitis, it also caused significant harm through invasive testing, unnecessary antibiotic exposure, and hospitalization-related complications. Management has shifted toward a more nuanced approach that emphasizes careful risk stratification, the use of biomarkers, and shared decision-making with families—while still respecting the reality that missed neonatal meningitis may portend a catastrophic outcome.

This evolution is reflected in a shift in terminology. The older term serious bacterial infection (SBI) grouped together urinary tract infection, bacteremia, and bacterial meningitis. The latest frameworks instead focus on invasive bacterial infection (IBI), as outlined in the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guidelines, which is defined strictly as bacteremia and bacterial meningitis, excluding UTIs. This distinction matters. UTIs are common, generally easier to identify, and urinalysis performs well as a screening test. In contrast, the true “can’t-miss” diagnosis is bacterial meningitis. Even within IBI, meningitis and bacteremia are not equivalent in clinical consequence—meningitis generally carries more morbidity and mortality than bacteremia—and recent studies and decision tools increasingly evaluate meningitis risk separately rather than treating all infections as a single composite outcome.

PECARN Febrile Infant Prediction Tool

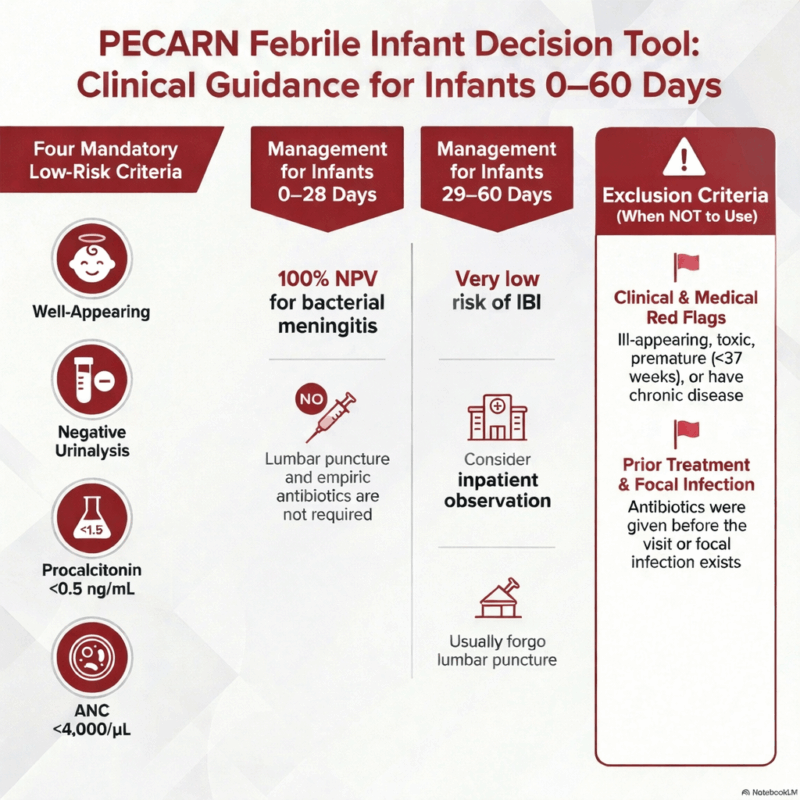

The PECARN Febrile Infant Prediction Tool tool should be used for well-appearing febrile infants <60 days of age. The reason for the new 0–28-day focus: earlier PECARN studies had fewer infants in the first month, so precision was limited; this pooled analysis was done to improve confidence specifically in that age range. The term prediction tool rather than “decision rule,” emphasizing that it estimates risk and should augment—not replace—clinical judgment.

Age Group PECARN Low-Risk Criteria (ALL must be present) Implications if ALL Criteria Met 0–28 days • Well appearing• Negative urinalysis• Procalcitonin < 0.5 ng/mL• ANC < 4,000/µL • 100% NPV for bacterial meningitis• Lumbar puncture NOT required• Admit with no empiric meningitis antibiotics required 29–60 days • Well appearing• Negative urinalysis• Procalcitonin < 0.5 ng/mL• ANC < 4,000/µL • Very low risk of IBI• LP usually not required• Consider inpatient observation without empiric abx PECARN Exclusion Criteria (Do not apply tool if present)

Category Examples Appearance Ill-appearing, toxic, lethargic Gestational age Prematurity (<37 weeks) Medical history Chronic disease, immunodeficiency Prior treatment Antibiotics before ED visit Source Focal bacterial infection on exam

Core principles in risk assessment of young febrile infants

- Fever should be considered binary (≥38°C or <38°C) in decisions around whether or not to work-up a young infant with fever, despite evidence suggesting that the height of fever is more likely to be of a bacterial cause than a viral one

- Home-documented fever by reliable method counts as fever even if afebrile at triage

- Appearance can be misleading in young infants – well-appearing young infants may harbor serious infections

- White blood cell count is unreliable with very poor test characteristics for IBI

- Partial workups create false reassurance

Pitfall: Viral symptoms or a confirmed viral diagnosis does reduce but do not eliminate bacterial risk; concomitant IBI still occurs and viral status should not materially change initial IBI workup in this age group.

PECARN Febrile Infant Prediction Tool study design and results

P (Population)

Febrile infants aged 0–28 days, drawn from a pooled international cohort of >2,500 infants across six cohorts (primary analysis focused on four non-US cohorts).I (Intervention)

Application of the updated PECARN febrile infant decision rule (see above).C (Comparison)

Standard care / usual evaluation pathways (including routine lumbar puncture, empiric antibiotics, and admission).O (Outcomes)

Primary outcome: Invasive bacterial infection (IBI), defined as bacteremia or bacterial meningitis

Missed infections:

- 0 missed cases of bacterial meningitis

- 5 missed cases of bacteremia

Negative predictive value (NPV):

- 100% for bacterial meningitis

- 99.6% for all IBI

Number needed to LP to identify one case of bacterial meningitis: >2,000

Key Takeaway

In this large pooled international analysis, the updated PECARN rule demonstrated no missed bacterial meningitis in neonates 0–28 days old, supporting its safety for ruling out the true “can’t-miss” diagnosis while substantially reducing unnecessary lumbar punctures.Editorial: Note that some “missed” bacteremias may be contaminants, and even true bacteremia without meningitis typically safely tolerates short diagnostic delay if the infant is admitted and observed, as most true positive blood cultures declare within 24 hours.Biomarkers for detection of invasive bacterial infection in young infants: what matters and why

Ranked by accuracy for IBI detection:

- Procalcitonin (best) – rises earliest after infection

- C-reactive protein (CRP) – next best (better than ANC)

- Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) – helpful, but less accurate than CRP and PCT

- White blood cell count (worst – “no better than coin toss”)

Herpes Encephalitis and HSV: a separate pathway (don’t apply PECARN tool if HSV is being considered in the differential)

The PECARN febrile infant tool does not address HSV; infants at meaningful HSV risk (ill‑appearing, seizures, lethargy, abnormal neuro exam, vesicular rash, transaminitis, coagulopathy, concerning maternal or household HSV history) need a separate HSV‑focused evaluation, typically including LP and acyclovir. The overall HSV risk in febrile infants is approximately 1 in 1,000.

HSV Risk Score for Febrile Infants ≤60 Days

A simple HSV risk score can help identify febrile infants at extremely low risk for invasive HSV, supporting more selective use of lumbar puncture, HSV testing, and empiric acyclovir—without missing meningitis.

Purpose:

Identify infants at very low risk for invasive HSV (CNS or disseminated disease) who may not require routine HSV testing or empiric acyclovir.Step 1: Assess Clinical Risk Factors

Assign points for each predictor present:

Risk Factor Points Age <14 days +3 Age 14–28 days +2 Prematurity (<37 weeks) +1 Seizure at home +2 Ill appearance +2 Abnormal triage temperature +1 Vesicular rash +5 Thrombocytopenia +1 CSF pleocytosis +1 Total Score Range: 0–17

Step 2: Interpret the Score

Total Score Clinical Interpretation 0–2 (Low Risk) Extremely low risk for invasive HSV ≥3 (Higher Risk) Increased risk for invasive HSV Test Characteristics (Cut-Point ≥3)

- Sensitivity for invasive HSV: 95.6%

- Negative predictive value: Very high

- Negative likelihood ratio: 0.11

- AUC: 0.85

No missed cases of HSV meningitis at this threshold in the study.

How to Use This Clinically

Score <3:

- Consider withholding routine HSV PCR testing and empiric acyclovir

- Ensure reliable follow-up and reassessment

Score ≥3:

Test for HSV and start empiric acyclovir pending results

Important Caveats

- Vesicular rash or seizures should strongly push toward treatment regardless of score

- Always consider local practice patterns and shared decision-making

Urinalysis collection when applying the PECARN febrile young infant prediction tool

- American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines now accept bag urine collection if negative

- If bag urine is positive, proceed to catheterization for repeat urinalysis and culture

- Never send bag urine for culture due to contamination risk

- Canadian guidelines still recommend catheterization for febrile young infants

Management recommendations for low-risk infants by the PECARN febrile young infant prediction tool

For infants 0–28 days old who meet low-risk PECARN criteria—specifically a negative urinalysis, procalcitonin <0.5 ng/mL, and an absolute neutrophil count <4,000/µL—the recommended management is hospital admission for observation. In these infants, lumbar puncture is deferred and empiric antibiotics are not started initially, unless there is a change in clinical status or culture results return positive.

When procalcitonin is unavailable: Are ANC and CRP good enough?

A major area of controversy emerges when procalcitonin (PCT) is unavailable. One of our guest experts recommends that extending the PECARN rule into the first month of life is only appropriate when PCT is available. Our other guest expert explains that in centers where access to PCT is more limited, clinicians often rely on alternative pathways. These include the Aronson rule, a point-based system using ANC for infants 0–

60 days, or the AAP consensus approach, which combines CRP <20 mg/L, temperature <38.5°C, and ANC <5,200/µL. These strategies prioritize safety and have high sensitivity, but their poor specificity means many infants are labeled high risk, leading to more admissions, LPs, antibiotics, and workups.

The broader theme is that while CRP- and ANC-based pathways may be safe, they often undermine the goal of “doing less.” For infants 0–28 days old, the best-supported strategy to safely avoid LPs and empiric antibiotics appears to depend heavily on access to procalcitonin. A combined CRP-plus-PCT approach may ultimately prove optimal, but this requires further study. Until then, a key takeaway is to advocate for access to PCT if you regularly manage febrile young infants, as it is central to the most evidence-based, less invasive care pathway currently available.

Common pitfalls in the risk stratification and workup of febrile young infants

- Discounting properly documented home fever when infant afebrile at triage

- Assuming viral symptoms or positive viral testing rules out bacterial infection

- Relying on appearance alone in early presentation

- Using white blood cell count for risk stratification

- Performing partial workups

Shared Decision-Making in applying the PECARN febrile young infant prediction tool

Shared decision-making is a key part of managing febrile young infants, especially around whether to perform a lumbar puncture. Parents consistently report that LP is the intervention they most want to avoid, often more than hospital admission or antibiotics. The strength of this PECARN study is that it provides quantified risk, allowing clinicians to have a clear, informed conversation rather than relying on reassurance alone.

For infants who meet low-risk criteria, the estimated risk of missed bacterial meningitis is less than 1 in 2,000. Putting this in context can help—other accepted decision rules, such as the PECARN head CT rule, accept similar negative predictive values, while these febrile infants are still being admitted for observation, not discharged. A typical discussion explains that although LP was historically routine, newer data allow identification of infants at extremely low risk. Families can choose admission with close observation without LP or empiric antibiotics, with a clear plan to escalate care if the exam changes or cultures turn positive. Some parents may still choose LP for zero-risk tolerance, but most prefer avoiding it when the risk is clearly explained.

Key Take-Home Points for PECARN Febrile Young Infant Prediction Tool

- The historical term serious bacterial infection (SBI) is overly broad and can be misleading; urinary tract infections are common but rarely life-threatening. Recent frameworks shift focus to invasive bacterial infection (IBI) — bacteremia and bacterial meningitis — which drive morbidity and mortality, and specifically meningitis which is the most dangerous.

- In febrile infants aged 0–28 days who meet low-risk criteria, the PECARN febrile infant prediction tool has a 100% negative predictive value for bacterial meningitis.

- In these carefully selected low-risk neonates, lumbar puncture is not required, and empiric meningitis antibiotics are not necessary.

- PECARN should only be applied after strict exclusion criteria are met, including well appearance, reassuring history, and absence of focal bacterial infection.

- PECARN does not apply when herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis is a concern.

- Red flags for HSV include seizures, focal neurologic findings, vesicular rash, hypothermia, maternal or household vesicular rash, or toxic appearance.

References

- Pantell RH, Roberts KB, Adams WG, et al. Evaluation and management of well-appearing febrile infants 8 to 60 days old. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021052228. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052228.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Febrile Infants. Clinical practice guideline: evaluation and management of well-appearing febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021052228.

- Burstein B, Robinson J, Guttmann A, et al. Management of well-appearing febrile young infants aged ≤90 days. Paediatr Child Health. 2023;28(1):23-34. doi:10.1093/pch/pxac036.

- Kuppermann N, Dayan PS, Levine DA, et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify febrile infants 60 days and younger at low risk for serious bacterial infections. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):342-351.

- Burstein B, Louie JP, Jain S, et al. Prediction of bacteremia and bacterial meningitis among febrile infants ≤28 days using the PECARN rule: a pooled international cohort analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(1):e244321.

- Kuppermann N, et al. Performance of the PECARN febrile infant rule in neonates 28 days and younger. Pediatrics. 2023;151(3):e2022059276.

- Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM. Bacteremia in previously healthy febrile infants aged 1 to 90 days. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e590-e596.

- Aronson PL, Thurm C, Alpern ER, et al. Variation in care of febrile infants ≤60 days across pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):667-677.

- Yo CH, Hsieh PS, Lee SH, et al. Comparison of the test characteristics of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and leukocyte count for detecting serious bacterial infection in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(10):1137-1145.

- Gomez B, Mintegi S, Bressan S, et al. Validation of the “step-by-step” approach in the management of young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154381.

- Norman-Bruce H, Bevan C, McNaughton C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for invasive bacterial infection in febrile infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2024;8(2):89-99.

- Biondi EA, Mischler M, Jerardi KE, et al. Blood culture time to positivity in febrile infants with bacteremia. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):844-849.

- Kuzniewicz MW, Puopolo KM, Fischer A, et al. Time to positivity of neonatal blood cultures for early-onset sepsis. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20191507.

- Cruz AT, Freedman SB, Kulik DM, et al. Predictors of invasive herpes simplex virus infection in young infants. Pediatrics. 2021;147(2):e2020020660.

- Shah SS, Aronson PL, Mohamad Z, et al. Delayed acyclovir therapy and death among neonates with herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1153-1160.

- Aronson PL, Shapiro ED, Meisel ZF, et al. A prediction model to identify febrile infants ≤60 days at low risk of invasive bacterial infection. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183604.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection. Urinary tract infection in infants and young children: clinical practice guideline. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):595-610.

- Aronson PL, Yau C, Helfaer MA, et al. Parents’ perspectives on communication and shared decision-making for febrile infants ≤60 days. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(2):119-127.

- Sylvestre P, Gravel J, Daoust R, et al. Parental preferences and shared decision-making in the evaluation of febrile infants. Acad Emerg Med. 2024;31(2):167-176.