Update 1/22/2016: Soon after I initially posted this entry I found an even more helpful podcast resource on pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis from Emergency Medicine Cases: Episode 63 – Pediatric DKA. It turns out that in the pediatric office, the biggest challenge is diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis in the child without a history of known Diabetes. What follows is from Reference (1) Episode 63 – Pediatric DKA.

Why can Pediatric DKA be easy to miss?

In a child without a known history of diabetes, making the diagnosis of DKA can be difficult, especially in the mild cases where symptoms can be quite vague. If we don’t have a high level of suspicion we can easily miss cases of early DKA. Thus, the diagnosis should be considered or ruled out if any of the following are present:

- Abdominal pain

- Isolated vomiting

- Polyuria or polydipsia

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Known diabetes

- Specific high risk groups (ie. Teenagers, children on insulin pumps and those from lower socio-economic status).

Remember that glucose should be considered the sixth vital sign and any “sick” appearing child should have a point of care glucose done!

Once DKA is suspected, elements on history should focus on screening for symptoms of diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia, enuresis ,weight loss) as well as symptoms of DKA (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased alertness). However, be sure to take the assessment one step further and consider any precipitating causes (viral or bacterial illness, social factors etc).

What follows is also from Reference (1) Episode 63 – Pediatric DKA show notes:

Pediatric DKA was identified as one of key diagnoses that we need to get better at managing in a massive national needs assessment conducted by the fine folks at TREKK – Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids – one of EM Cases’ partners who’s mission is to improve the care of children in non-pediatric emergency departments across the country. You might be wondering – why was DKA singled out in this needs assessment?

It turns out that kids who present to the ED in DKA without a known history of diabetes, can sometimes be tricky to diagnose, as they often present with vague symptoms. When a child does have a known history of diabetes, and the diagnosis of DKA is obvious, the challenge turns to managing severe, life-threatening DKA, so that we avoid the many potential complications of the DKA itself as well as the complications of treatment – cerebral edema being the big bad one.

The approach to these patients has evolved over the years, even since I started practicing, from bolusing insulin and super aggressive fluid resuscitation to more gentle fluid management and delayed insulin drips, as examples. There are subtleties and controversies in the management of DKA when it comes to fluid management, correcting serum potassium and acidosis, preventing cerebral edema, as well as airway management for the really sick kids. In this episode we‘ll be asking our guest pediatric emergency medicine experts Dr. Sarah Reid, who you may remember from her powerhouse performance on our recent episodes on pediatric fever and sepsis, and Dr. Sarah Curtis, not only a pediatric emergency physician, but a prominent pediatric emergency researcher in Canada, about the key historical and examination pearls to help pick up this sometimes elusive diagnosis, what the value of serum ketones are in the diagnosis of DKA, how to assess the severity of DKA to guide management, how to avoid the dreaded cerebral edema that all too often complicates DKA, how to best adjust fluids and insulin during treatment, which kids can go home, which kids can go to the floor and which kids need to be transferred to a Pediatric ICU.

______________________________________________________

The protocol in this post only covers the initial diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in a primary care pediatric office (primary care family practice or internal medicine office). The most dreaded complication of pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis is cerebral edema – see the references in Resources. But the best place to go for immediate clear info on DKA cerebral edema is the post, Cerebral Edema and Diabetic Ketoacidosis BY SEAN FOX · FEBRUARY 21, 2014, from Dr. Fox’s outstanding blog – Pediatric EM Morsels.

The following treatment protocol is from Reference (2) in Resources:

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a decrease in effective circulating insulin associated with increase in counter regulatory hormones (e.g., glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, and growth hormone). Hyperglycemia and acidosis result in osmotic diuresis, dehydration, and electrolyte loss. The biochemical criteria included blood glucose greater than 200 mg/dL; venous pH of less than 7.25 (and arterial pH of less than 7.3); and/or bicarbonate of less than 15 mmol per liter. In the office elevated blood glucose with glucosuria and ketonuria in the appropriate clinical setting is enough to suspect DKA and refer the child to the emergency department.

History:

- New or established type I diabetes (IDDM)

- Age

- Concurrent illness

- Estimated weight loss

- Abdominal pain or vomiting

- Altered mental status

- Last dose of insulin: amount and time

Assessment:

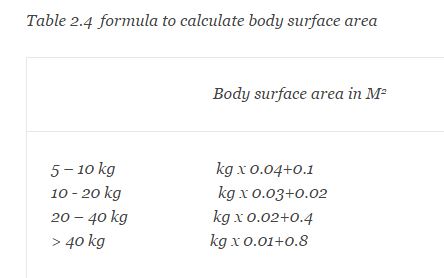

- Pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, weight, length. Calculate the body surface area (table 2.4)

High-Risk children:1. Age <5 years 2. Level of consciousness: AVPU or Glasgow coma scale [Dr Fox, citing an article in his post states that the GCS is not sensitive enough to detect Cerebral Edema in Pediatric DKA and suggests an alternative] Kussmal’s breathing (rapid and/or deep sighing) 3. Dehydration: cool skin, diaphoresis, week pulses, delayed capillary refill, hypotension, oliguria, somnolence 4. Cerebral edema: abnormal disk margins, inappropriately low heart rate, increased blood pressure, altered mental status [Please see link in 2 directly above]

- Age less than five years

- New onset IDDM

- Altered mental status

- Severe dehydration/shock, cardiac arrhythmias, or EKG changes

- Glucose greater than 800 mg/dL

- Cerebral edema (inappropriately low heart rate, increase in blood pressure, altered mental status)

Management: goal is to stabilize and rapidly transferred to the hospital for definitive (insulin and fluid) therapy

- Immediate bedside blood glucose level.

- Assess airway, place on monitor and pulse oximeter.

- Obtain IV access. If in shock, administer oxygen and fluid bolus (below).

- Lactated ringer (LR) 10 mL per kilogram bolus over one hour and if clinically indicated, repeat once (may use normal saline if LR is unavailable)

- Do not give sodium bicarbonate

- Total fluids: 2500 mL per meter squared per day (do not exceed 4000 mL per meter squared per day including bolus)

Transfer to hospital/call EMS when

- Diagnoses of DKA suspected

- Altered mental status

- Dehydration and shock

- Respiratory distress

Resources:

(1) Episode 63 – Pediatric DKA podcast and show notes from Emergency Medicine Cases.

(2) The Complete Resource on Pediatric Office Emergency Preparedness. 2013. Springer. This excellent book is brief and to the point. The authors are from Texas Children’s Hospital and Texas Children’s Pediatrics. pp 29 – 30.

(3) The Harriet Lane Handbook, Twentieth Edition, Elsevier Saunders, 2015. Diabetic Ketoacidosis, pp. 216 – 217.

(4) Pediatric Diabetic Ketoacidosis Treatment & Management, Updated: Apr 25, 2014. Emedicine – Medscape.

(5) Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics. [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jan 25;344(4):264-9.