In addition to what follows below, please see my post “Exercise Prescriptions in Older Adults” – Link To The 2017 AFP Article With Excerpts And Additional Resources.

The following are excerpts from (1) How to Write an Exercise Prescription [Full Text PDF]:

Exercise Prescription

D. Intensity

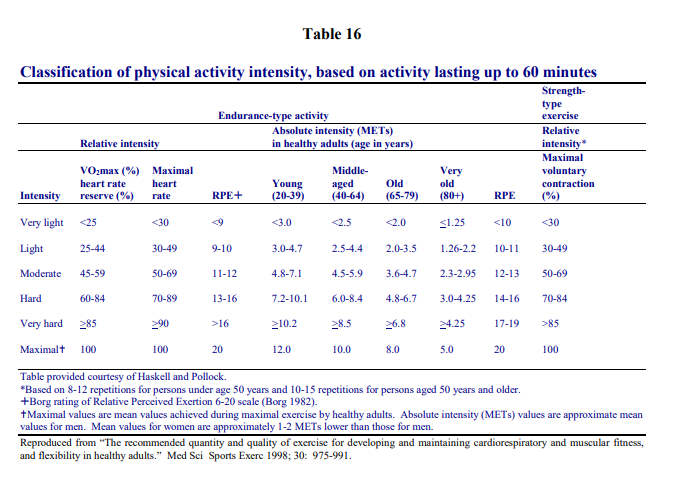

The final and most difficult aspect of the exercise prescription to write is intensity. The intensity should be specifically tailored to the patient’s performance goals. The optimal intensity for aerobic exercise training occurs between 50% to 85% of the functional aerobic capacity (VO2max). Deconditioned patients should start at 40% to 50% of their VO2max.78 VO2max represents the amount of oxygen transported and used in cellular metabolism during maximal exercise.

Exercise intensity can be prescribed by several methods, the most popular of which are utilization of the target heart rate; calculated VO2max; or category-ratio scales for rating of

perceived exertion.79 In most cases it is not feasible to directly measure oxygen uptake in patients. Studies show that heart rate and oxygen uptake are linearly related during peak exercise.63 Thus heart rate monitoring has become widely accepted as an indicator of exercise intensity.The recommended target heart rate (THR) should be 65% to 90% of maximum heart rate (MHR). This heart rate range is for improvement/maintenance of VO2max. Health-related benefits may be seen at lower heart rate ranges. This method of calculating THR has come under some scrutiny because the variability of age-predicted heart rate maximums. Furthermore, recent data suggest the use of the “220 minus the patients age” formula significantly underestimates the MHR, especially in the elderly population.80 [Emphasis Added]

The alternate method to calculate THR employs the use of heart rate reserve (HRR) – the Karvonen equation. First, calculate the MHR. Women subtract their age from 220 and men subtract one-half their age from 205. The second step is to determine the resting heart rate (RHR). Third, calculate the HRR. The HRR is MHR minus RHR. Lastly, the THR is the product of training intensity (TI), generally 60% to 80%, multiplied by the HRR then adding the RHR.

[THR = (MHR – RHR) x %TI + RHR]

For example, what is the THR for a 40 year old male with a RHR of 60 who is to exercise between 70% and 80% TI? His MHR is 205 minus 40 divided by 2, which equates to 185

beats per minute (BPM). Thus his HRR is 185 (MHR) minus 60 (RHR) which is 125 BPM. Seventy percent TI equals 0.7 (TI) multiplied by 125 (HRR) plus 60 (RHR). This figure calculates to 147.5 BPM. Eighty percent TI when calculated using the same formula yields 160 BPM. Thus this individual would have a THR ranging from 148 to 160 BPM.When a THR is calculated, the patient should be taught to monitor their heart rate at various stages of exercise.

The individual can easily learn to palpate the radial pulse.

But I think the best way to monitor your pulse is with an oximeter. The oximeter, in addition to giving your oxygen saturation, will measure your heart rate at the same time. You can get an oximeter for perhaps $25 at any pharmacy.

When the patient prefers not to monitor the heart rate or when, for clinical reasons, heart rate monitoring is inappropriate, the clinician can use the rate of perceived exertion (RPE):

Intensity can also be judged as a rating of perceived exertion (RPE), which can be equated to desirable heart rate during individual activities. The original scale introduced by Borg

in the early 1960’s is a 15 grade category scale ranging from 6 to 20, with a verbal description at every odd number that is an important adjunct to heart rate monitoring during training. The RPE scale provides valuable information related to the amount of strain or fatigue the patient is experiencing during exercise. The original scale was validated in a young population to represent the actual heart rate at a given level of work.

Unfortunately, heart rate maximums decline with age and therefore actual heart rates and

RPE do not match. Despite these findings, the linear relationship between heart rate and work intensity remains for individuals at all ages.76 The following rating of perceivedexertion values should be followed:81

- less than 12 – light, 40% to 60% of maximal

- 12 to 13 – somewhat hard (moderate), 60% to 75% of maximal

- 14 to 16 – hard (heavy), 75% to 90% of maximal

The RPE can be a very powerful tool, particularly in populations who are uncomfortable in measuring pulse, those with arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter), and patients

on drugs that slow the heart rate (e.g., beta-blockers, certain calcium channel blockers). The RPE can be performed safely, efficiently and accurately without interfering aerobic activity.E. The Exercise Session

A typical exercise session includes a warm-up period, a cardiorespiratory phase, and a cool-down period. Warm-up should last five to ten minutes and is designed to prepare the

body for transition from rest to the cardiorespiratory phase. A preliminary warm-up serves to stretch muscles, increase flexibility and gradually increases heart rate and circulation.

An appropriate warm-up will decrease the incidence of both orthopedic injury and the potential for adverse ischemic responses. Thus warm-up has musculoskeletal and cardiovascular preventive value. An ideal warm-up for the endurance phase of training should be the same activity only at a lower intensity.The cardiorespiratory phase of exercise should last 20 to 60 minutes at the individual’s predetermined heart rate range or rating of perceived exertion. This phase serves to stimulate oxygen transport and maximize caloric expenditure. There appears to be little additional cardiovascular benefit beyond 30 minutes of the endurance phase.82 Longer exercise sessions are also associated with a disproportionate incidence of musculoskeletal injuries.63 Improvement in VO2max increases linearly with increasing intensity of exercise to a peak of 80% VO2max with little additional cardiorespiratory benefit thereafter.

The cool-down period follows the cardiorespiratory phase and should last 5 to 10 minutes. The cool-down period again may be the same exercise only at a much lower intensity.

of a muscle-stretching or muscle lengthening nature are likewise encouraged. Specific muscle groups should include extensor muscle of the back, lower leg and upper extremity. These activities will gradually decrease the heart rate and blood pressure to near resting values.F. Rate of Progression

The provider’s first goal should be to engage the patient in a regular exercise program at an acceptable minimum frequency. Thereafter, emphasis is placed first on increasing frequency, second on increasing duration, and lastly, on increasing intensity. It is best to maximize the preceding variable prior to increasing subsequent variables.

The rates of progression can be separated into 3 phases: initial conditioning phase; improvement conditioning phase; and maintenance conditioning phase. The benefits derived from each of these phases will depend on the patient’s age, current level of fitness, intensity of their physical activity program and individual goals. In general, the benefits of physical activity represent a dose-response curve.

The initial conditioning phase lasts approximately 4 to 6 weeks. During this phase,

training effects should be appreciated. These are a decrease in resting heart rate, more

rapid recovery of resting heart rate following physical activity, and the ability to increase

duration and intensity without increasing fatigue.The improvement conditioning phase lasts approximately 4 to 6 months. Patients can be

progressed to reach target heart rates or desired duration of physical activity. It is best to

first increase the duration of activity to the desired length and then increase the intensity.

The patient will continue to enhance cardiorespiratory fitness resulting in improved

endurance and resistance to early fatigue.Most patients enter the maintenance conditioning phase after 6 months of regular

exercise. Individuals will have obtained the desired level of cardiorespiratory fitness and

do not need to increase their duration or intensity of exercise. Emphasis may be refocused

from an exercise program involving primarily fitness activities to one which includes a

more diverse array of enjoyable activities. Patients should be advised that different forms

of exercise or activities of similar intensity can be employed to maintain interest in

exercise.

Resources:

(1) How to Write an Exercise Prescription [Full Text PDF] MAJ Robert L. Gauer, MD, LTC Francis G. O’Connor, MD, FACSM. Department of Family Medicine: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

(2) Exercise Prescriptions in Older Adults [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Apr 1;95(7):425-432.