Resource (1) is the 2011 complete guide on managing patients with stable respiratory disease from the British Thoracic Society (BTS). As you review the excerpts in this post, you will note that the guideline also offers guidance on the use of oxygen therapy in other diseases such as congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, bronchiectasis and cancer, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension and other chronic conditions. All the chronic conditions discussed in the guideline are listed in this blog post and many of them are excerpted in the blog

Resource (2) is 2013 primary care summary of Resource (1).

And here is a link to all of the British Thoracic Society Guidelines.

The following are excerpts from Resource (1):

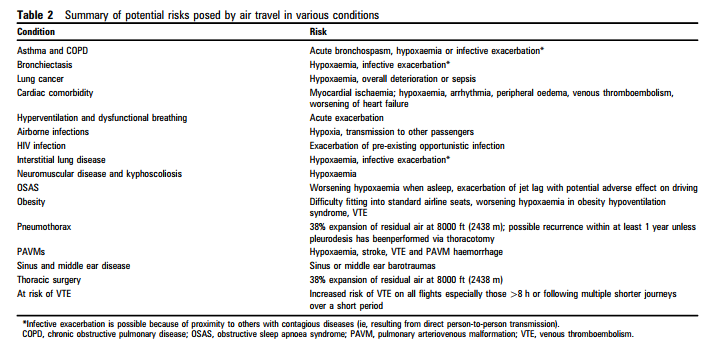

Pre-flight assessment for adults

If there is doubt about the patient’s fitness to fly and if there are comorbidities affecting fitness (such as cardiovascular disease or immunosuppressant therapy), assessment is advised. In general the patient should be stable and have recovered from any recent exacerbation before travel. We recommend that those with the following conditions should be assessed with history and examination as a minimum:

- Previous air travel intolerance with significant respiratory symptoms (dyspnoea, chest pain, confusion or syncope).

- Severe COPD (FEV1 30% predicted) or asthma.

- Bullous lung disease.

- Severe (vital capacity <1 litre) restrictive disease (including chest wall and respiratory muscle disease), especially with hypoxaemia and/or hypercapnia.

- Cystic fibrosis.

- Comorbidity with conditions worsened by hypoxaemia (cerebrovascular disease, cardiac disease or pulmonary hypertension).

- Pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Within 6 weeks of hospital discharge for acute respiratory illness.

- Recent pneumothorax.

- Risk of or previous venous thromboembolism

- Pre-existing requirement for oxygen, CPAP or ventilator support.

Contraindications to commercial air travel

- Infectious tuberculosis.

- Ongoing pneumothorax with persistent air leak. < Major haemoptysis.

- Usual oxygen requirement at sea level at a flow rate exceeding 4 l/min.

Hypoxic challenge testing (HCT)

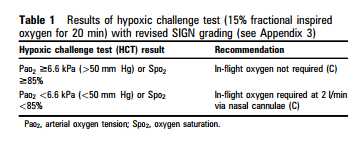

The hypoxic challenge test (HCT) is used to assess whether patients need in-flight oxygen; further research is needed to determine more precisely its place in assessing respiratory patients before air travel. There is currently no evidence to justify amending earlier advice for patients in whom the respiratory physician considers HCT is required. The HCT is performed in a specialist lung function unit after referral to a respiratory specialist. The UK Flight Outcomes Study showed that, even in specialist centres, only 10% of patients undergo a walk test as part of a fitness to fly assessment.6 We have therefore removed the earlier reference to walk tests.*

* Although a reference to walk tests has been removed from the 2011 Resource (1), it is to be noted that the improved and apparently well validated, 2012 Air Travel and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A New Algorithm for Pre-flight Evaluation – Resource (3), only became available in 2012 and is cited 2013 Primary Care Summary – Resource (2).

The recommended course of action, depending on the HCT result, is shown in table 1. Normal temperature and PaCO2 are assumed; results in hyperventilation must be interpreted with caution. Where there is doubt, it seems prudent to err on the side of recommending oxygen.

Logistics of travel with oxygen is discussed on pp i3 + i4.

Bronchiectasis and Cancer are discussed on p i4.

Cardiac comorbidity

The British Cardiovascular Society recently published guidance for air passengers with cardiovascular disease.30 However, since cardiac and pulmonary conditions often coexist and respiratory physicians are often consulted about HCT in cardiac patients, we felt it appropriate to retain this section in our current recommendations. Physicians should use their discretion to undertake HCTor recommend in-flight oxygen for patients with coexistent cardiac and pulmonary disease. Where measured haemodynamics or correlates of ventricular function are more severe than symptoms suggest, physician discretion should determine use of in-flight oxygen.

Coronary artery disease

At 8000 ft (2438 m) there is a 5% fall in ischaemic threshold

(measured as the product of heart rate and systolic blood pressure at the ECG threshold for ischaemia).31

- Patients who have undergone elective percutaneous coronary intervention can fly after 2 days (C).

- Patients at low risk after ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)dnamely, restored TIMI grade 3 flow on angiography, age <60, no signs of heart failure, normal ejection fraction and no arrhythmias – can fly after 3 days (C).

- Other patients may travel 10 days after STEMI unless awaiting further investigation or treatment such as revascularisation or device implantation. (C) For those with complications such as arrhythmias or heart failure, advice in the relevant section below should be followed.

- Patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) should undergo angiography and revascularisation before considering air travel (C).

- Patients who have undergone uncomplicated coronary artery bypass grafting should be able to fly within 14 days but must first have a chest x-ray to exclude pneumothorax (C).

- Patients with stable angina up to Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) functional class III are not expected to develop symptoms during commercial air travel (C).

- Patients with CCS functional class IV symptoms (defined as the inability to carry on any activity without discomfort), who may also get stable angina at rest, should be discouraged from flying. (C) If air travel is essential they should receive in- flight oxygen at 2 l/min and a wheelchair is advisable (C).

- Patients with unstable angina should not fly (D).

Cyanotic congenital heart disease

- Physicians should use their discretion in deciding whether to perform HCT and/or advise in-flight oxygen (O).

- Those in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class IV should avoid air travel unless essential. If flying cannot be avoided, they should receive in-flight oxygen at 2 l/min (D).

Heart failure

- Patients who are hypoxaemic at sea level with coexistent lung and/or pulmonary vascular disease should be considered for HCT (D).

- Patients in NYHA functional class IeIII (without significant pulmonary hypertension) can fly without oxygen (C).

- Patients with severe disease in NYHA functional class IV should not fly unless essential. If air travel cannot be avoided, they should have in-flight oxygen at 2 l/min (C).

Hypertension

- Patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension should have it controlled before embarking on commercial air travel (D).

Pulmonary hypertension

- Those in NYHA functional class I or II can fly without oxygen (D).

- Those in NYHA functional class III or IV should receive in- flight oxygen (D).

Rhythm disturbance, pacemakers and defibrillators

Modern pacemakers and defibrillators are compatible with aircraft systems.

- Patients with unstable arrhythmias should not fly (C).

- Patients with high-grade premature ventricular contractions (Lown grade >/= 4b) should be discouraged from flying, but may fly at the physician’s discretion with continuous oxygen at 2 l/min (D).

Valvular disease

- Patients with valvular disease causing functional class IV symptoms, angina or syncope should use in-flight oxygen at 2 l/min if air travel is essential (D).

Hyperventilation and dysfunctional breathing, Airborne infections, Airborne infections, and Interstitial lung disease are discussedf on p. i5.

Neuromuscular disease and kyphoscoliosis

- All patients with severe extrapulmonary restriction, including those needing home ventilation, should undergo HCT before travel (C).

- The decision to recommend in-flight oxygen and/or noninvasive ventilation must be made on an individual clinical basis (D).

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, Obesity, Pneumothorax, Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs), and Thoracic surgery are discussed on p i6.

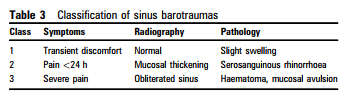

Sinus and middle ear disease

- Adults with risk factors for sinus or middle ear barotrauma (mucosal oedema, bacterial infection, thick mucin, intrasinus and extrasinus pathology and tumours) should receive an oral decongestant before travel and a nasal decongestant spray during the flight just before descent (D).

- Women in the first trimester of pregnancy may wish to take intranasal steroids instead of topical decongestants (D).

- Passengers who develop sinus barotrauma after flying should receive topical and oral decongestants, analgesics and oral steroids (D).

- Antibiotics are advised if bacterial sinusitis is thought to be the trigger, and antihistamines if allergic rhinitis is suspected (D).

- Symptoms and signs of barotrauma should have resolved before flying again; some recommend plain radiography to ensure that mucosal swelling has settled. This usually takes at least a week and may take up to 6 weeks (D).

- Recurrent sinus barotrauma is usually only seen in military air crew and has been shown to respond to functional endoscopic sinus surgery (D).

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) for flights >8 h or multiple shorter journeys over a short period

The evidence is unclear, current guidelines conflicting and recommendations controversial. Patients are usually stratified into three groups, but physicians may wish to make decisions on an individual case-by-case basis as the evidence for any particular recommendation is limited and firm guidelines cannot be formulated. The risk of VTE is greatest on flights lasting >8 h and is reduced if passengers occupy an aisle seat.

Low risk of VTE: all passengers not in the categories listed below.

- Passengers should avoid excess alcohol and caffeine containing drinks, and preferably remain mobile and/or exercise their legs during the flight (D).

Moderately increased risk of VTE:

- family history of VTE,

- past history of provoked VTE,

- thrombophilia,

- obesity (BMI >30 kg/ m2 ),

- height >1.90 m or <1.60 m,

- significant medical illness within previous 6 weeks,

- cardiac disease,

- immobility,

- pregnancy or oestrogen therapy (including hormone replacement therapy and some types of oral

- contraception) and postnatal patients within 2 weeks of delivery.

- < Patients should be advised to wear below-knee elastic compression stockings as well as the following recommendations for low-risk passengers. They should be advised against the use of sedatives or sleeping for prolonged periods in abnormal positions. (D)

- Passengers with varicose veins may be at risk of superficial thrombophlebitis with use of stockings; the risk/benefit ratio here is unclear.

Greatest increased risk of VTE:

- past history of idiopathic VTE,

- those within 6 weeks of major surgery or trauma and active malignancy

- There is no evidence to support the use of low- or high-dose aspirin.

- < Pre-flight prophylactic dose of low molecular heparin should be considered or formal anticoagulation to achieve a stable INR of 2e3 for both outward and return journeys, and decisions made on a case-by-case basis. These recommendations are in addition to general advice for those at low to moderate risk (D).

- < Patients who have had a VTE should ideally not travel for 4 weeks or until proximal (above-knee) deep vein thrombosis has been treated and symptoms resolved, with no evidence of pre- or post-exercise desaturation. (D)

THE BACKGROUND LITERATURE REVIEW discusses the evidence base for all of the recommendations above. It runs from pp i7 – i24. The section is very much worth reviewing.

Resources:

(1) Managing passengers with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Thorax. 2011 Sep;66 Suppl 1:i1-30. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200295.

(2) Managing patients with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: a primary care summary of the British Thoracic Society recommendations [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Prim Care Respir J. 2013 Jun;22(2):234-8. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00046.

(3) Air Travel and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A New Algorithm for Pre-flight Evaluation [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] Edvardsen A, Akerø A, Christensen CC, Ryg M, Skjønsberg OH Thorax. 2012;67:964-969