Today, I review, link to and excerpt from The Cribsiders‘ #81: Pediatric Brain Tumors – Let’s Think About It!* March 29, 2023 | By Sam Masur.

*Holloway R, Hummel T, Lee N, Mao C, Masur S, Chiu C, Berk J. “#81: Pediatric Brain Tumors – Let’s Think About It!”. The Cribsiders Pediatric Podcast. https:/www.thecribsiders.com/ March 29, 2023.

All that follows is from the above resource.

AUDIO

Summary:

Brain tumors can be intimidating, for families and providers alike! Tune into this episode as Dr. Trent Hummel, Pediatric Neuro-Oncologist, guides us through the red flags to look for, when to escalate care and how to approach discussions with families. This conversation will blow your mind!

Pediatric Brain Tumor Pearls

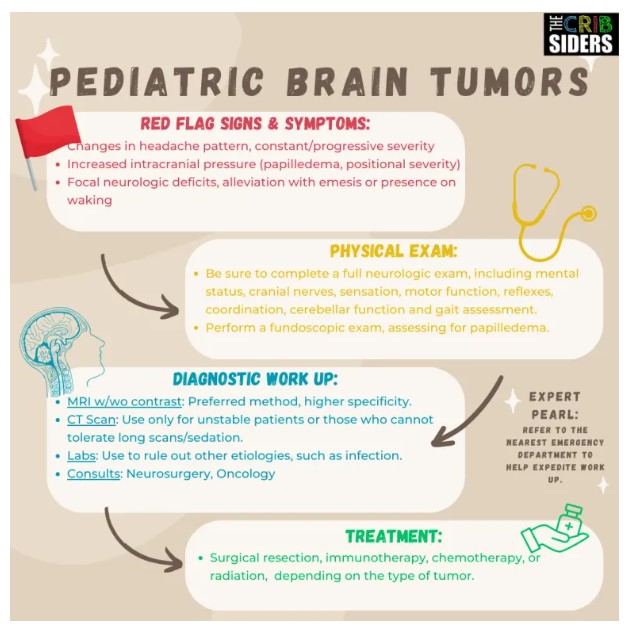

- When a patient presents with headache, be on the lookout for red-flag signs and symptoms, including severe and sudden onset, persistent and progressive pain, pain upon waking in the morning, alleviation of pain with vomiting or new-onset neurologic symptoms (frequent falls, dizziness, lack of use of an extremity, etc.).

- In addition to obtaining a symptom history, be sure to take a thorough past medical history, medication reconciliation and social history, looking for pertinent factors such as smoking or drug use.

- Complete a thorough neurologic and fundoscopic exam in patients with red flag symptoms.

- If you have concern for a potential mass-like process, you should have a low threshold for obtaining imaging. CT scans are good for screening, and MRIs are more definitive. Take into consideration your patient’s individual factors (ability to tolerate longer scans, ability to undergo sedation, etc.) and your level of concern in deciding which imaging is best.

- Obtain lab work judiciously – consider a complete blood count and a renal panel to assess for anemia/leukocytosis and electrolyte abnormalities, respectively.

- In cases in which you have high concern for a brain mass, consider referring to an Emergency Department to expedite work up.

- The majority of pediatric brain tumors are in the posterior fossa (60%). The most common types, in decreasing frequency, include medulloblastoma, juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma (JPA), ependymoma, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT). The other 40% of pediatric brain tumors are in the cerebral hemispheres of the brain, and include astrocytomas, gangliogliomas, craniopharyngiomas and meningiomas, amongst others. [1]

- Depending on the type of tumor, treatment can range from various combinations of surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation and/or immunotherapy.

- Minority groups are traditionally under-represented in clinical trials, and often have difficulty accessing quality care for their child’s tumor.

Pediatric Brain Tumor Notes

Patient History

- Key history components include: location of pain, characteristics, onset, timing, duration, alleviating and aggravating factors, and associated symptoms (e.g., focal weakness, dizziness, loss of consciousness, increased falls, vomiting that alleviates pain, waking from sleep, phono/photophobia).

- In younger kids who may have more difficulty verbalizing their symptoms, parents may notice things like not eating as well, increased vomiting, poor growth/development, fussiness or increased clumsiness (i.e., running into walls).

- Expert Opinion: Oftentimes, a parent will have concern that something is different than before, though they may be unable to specify or verbalize what exactly is different. Dr. Hummel recommends taking this “parent’s intuition” into account.

- Other important history questions include: family history of migraines or headaches (strong predictor of benign headaches), a thorough medication reconciliation (e.g., contraceptive pill or acne medications, which could make other benign differential diagnoses such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension more likely), and a thorough social history (e.g., smoking, caffeine, alcohol or other drug use, stress, trauma).

History Red Flags

- Systemic symptoms (e.g., fever, signs of meningitis, myalgia, malaise)

- Neurological deficits/dysfunction (e.g., altered mental status, weakness, seizures)

- Severity of headache is constant and progressive

- Pattern changes of headache or recent onset (pearl: symptom onset in primary brain tumors is usually insidious, while symptom onset in patients with brain metastases is typically acute or subacute).

- Positional headache

- Papilledema and other signs of increased ICP

- Visual deficits

- Pain on waking in the morning

Physical Exam

- Complete neurologic exam, including mental status, cranial nerves, sensation, motor function, reflexes, coordination, cerebellar function and gait assessment. Be on the lookout for nystagmus, focal neurologic deficits or signs of cerebellar dysfunction, which can be present in patients with brain tumors.

- Fundoscopic exam, assessing for papilledema (sign of increased intracranial pressure). Tips include: In a dark room, have the patient fixate on a target as far as possible in the room to best dilate the eye. Angle the fundoscope 15 degrees lateral to the patient’s line of sight, and identify the red reflex by slowly approaching the patient until the instrument is 2-4 cm from the eye. Angle the ophthalmoscope to visualize the structure of the eye, starting with branching blood vessels. Once you have identified a blood vessel, follow it in towards the optic disc. Assess for papilledema (a blurred, swollen disc). Other tips and abnormal findings can be found at this site. [2]

Diagnostic Work Up

- In a patient with concern for a brain mass, Dr. Hummel recommends having a low threshold for imaging. You can refer to your nearby Emergency Department to expedite the process.

- CT scan: Good for screening in patients who are unstable, cannot tolerate long scans or sedation. Order without contrast, as this will be sufficient to identify a mass. If you have concern for other metabolically active etiologies like infection, you can consider a CT scan with/without contrast.

- MRI with/without contrast: Preferred method of imaging in patients who are stable, can tolerate long scans and/or can tolerate sedation. Lookout for kids with decreased renal function and consider omitting contrast.

- Labs: Labs have little function in diagnosing brain tumors outside of ruling out other etiologies, such as infection. That said, Dr. Hummel recognizes the utility of a CBC to assess for anemia/leukocytosis and a renal panel to assess for electrolyte abnormalities.

- Pearl: In patients with hydrocephalus, there can be pituitary involvement leading to precocious puberty, short stature or panhypopituitarism.

- Consults: If imaging shows a mass, consult your friendly neighborhood neurosurgeon and oncologist.

Communicating Bad News

- Find tips on breaking bad news at this American Academy of Family Physicians article. [3]

- Dr. Hummel recommends using the phrasing, “mass”, in place of definitive words like “malignant” or “cancer”. This is often unsettling to parents and can be premature.

- Dr. Hummel emphasizes the importance of defining benign, malignant and metastatic. “Benign” refers to well-differentiated tumors that have slow growth, and often do not recur after resection. “Malignant” refers to poorly-differentiated tumors with unpredictable growth and metastatic potential, and often recur after resection. “Metastatic” refers to the ability of cancer to disseminate from the primary site of cancer to other parts of the body. While all tumors will have an impact on the life of a child, it is important to be accurate when discussing brain masses with families.