In addition to today’s resource, please see and review:

- Links To And Excerpts From The “2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Evaluation and Disposition of Acute Chest In The Emergency Department” With Links To Additional Resources

Posted on August 30, 2023 by Tom Wade MD - the outstanding YouTube lecture, The Role of Coronary CTA in the New Guideline Era, from Yale Cardiovascular Medicine Grand Rounds, 1:07:31, Jan 11, 2022, by Todd C. Villenes, MD.

See also 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. [PubMed Abstract]. Circulation

. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from 2021AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Circulation

. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029. Epub 2021 Oct 28.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Jump to

- Abstract

- Contents

- Top 10 Take-Home Messages for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain

- Preamble

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Initial Evaluation

- 3. Cardiac Testing General Considerations

- 4. Choosing the Right Pathway With Patient-Centric Algorithms for Acute Chest Pain

- 5. Evaluation of Patients With Stable Chest Pain

- 6. Evidence Gaps and Future Research

- ACC/AHA Joint Committee Members

- Staff

- Footnotes

- References

- Supplementary Materials

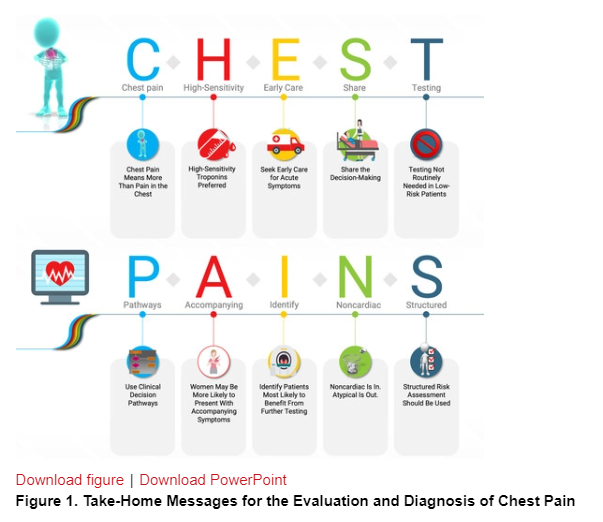

Top 10 Take-Home Messages for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain

Chest Pain Means More Than Pain in the Chest. Pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort in the chest, shoulders, arms, neck, back, upper abdomen, or jaw, as well as shortness of breath and fatigue should all be considered anginal equivalents.

High-Sensitivity Troponins Preferred. High-sensitivity cardiac troponins are the preferred standard for establishing a biomarker diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, allowing for more accurate detection and exclusion of myocardial injury.

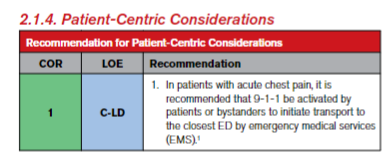

Early Care for Acute Symptoms. Patients with acute chest pain or chest pain equivalent symptoms should seek medical care immediately by calling 9-1-1. Although most patients will not have a cardiac cause, the evaluation of all patients should focus on the early identification or exclusion of life-threatening causes.

Share the Decision-Making. Clinically stable patients presenting with chest pain should be included in decision-making; information about risk of adverse events, radiation exposure, costs, and alternative options should be provided to facilitate the discussion.

Testing Not Needed Routinely for Low-Risk Patients. For patients with acute or stable chest pain determined to be low risk, urgent diagnostic testing for suspected coronary artery disease is not needed.

Pathways. Clinical decision pathways for chest pain in the emergency department and outpatient settings should be used routinely.

Accompanying Symptoms. Chest pain is the dominant and most frequent symptom for both men and women ultimately diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome. Women may be more likely to present with accompanying symptoms such as nausea and shortness of breath.

Identify Patients Most Likely to Benefit From Further Testing. Patients with acute or stable chest pain who are at intermediate risk or intermediate to high pre-test risk of obstructive coronary artery disease, respectively, will benefit the most from cardiac imaging and testing.

Noncardiac Is In. Atypical Is Out. “Noncardiac” should be used if heart disease is not suspected. “Atypical” is a misleading descriptor of chest pain, and its use is discouraged.

Structured Risk Assessment Should Be Used. For patients presenting with acute or stable chest pain, risk for coronary artery disease and adverse events should be estimated using evidence-based diagnostic protocols.

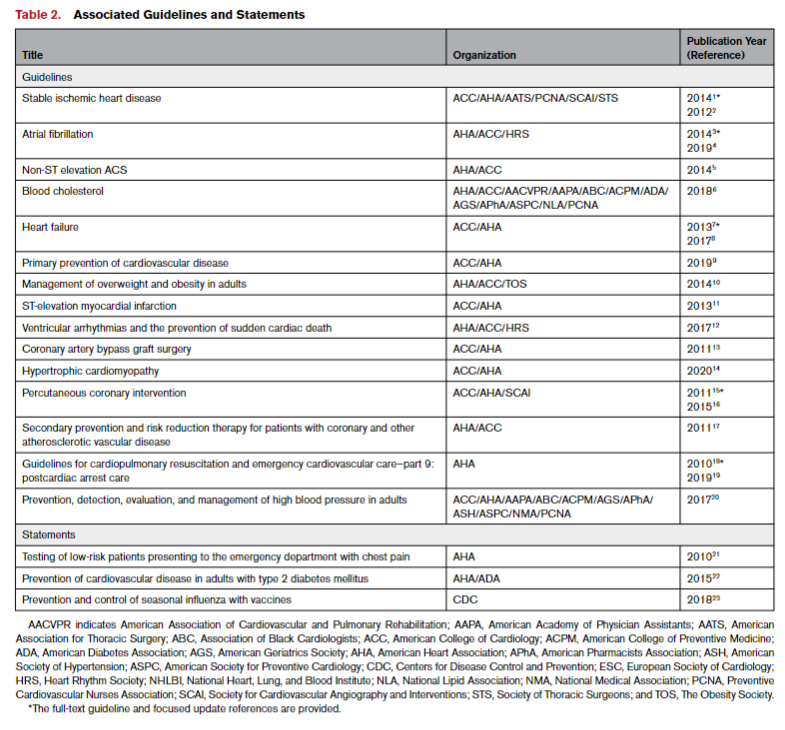

1.4. Scope of the Guideline

The charge of the writing committee was to develop a guideline for the evaluation of acute or stable chest pain or other anginal equivalents, in various clinical settings, with an emphasis on the diagnosis on ischemic causes. This guideline will not provide recommendations on whether revascularization is appropriate or what modality is indicated. Such recommendations can be found in the forthcoming ACC/AHA coronary artery revascularization guideline.* In developing the “2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain,” the writing committee first reviewed previous published guidelines and related statements. Table 2 contains a list of these publications deemed pertinent to this writing effort and is intended for use as a resource, thus obviating the need to repeat existing guideline recommendations.

*2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Jan 18;79(2):e21-e129.

Synopsis

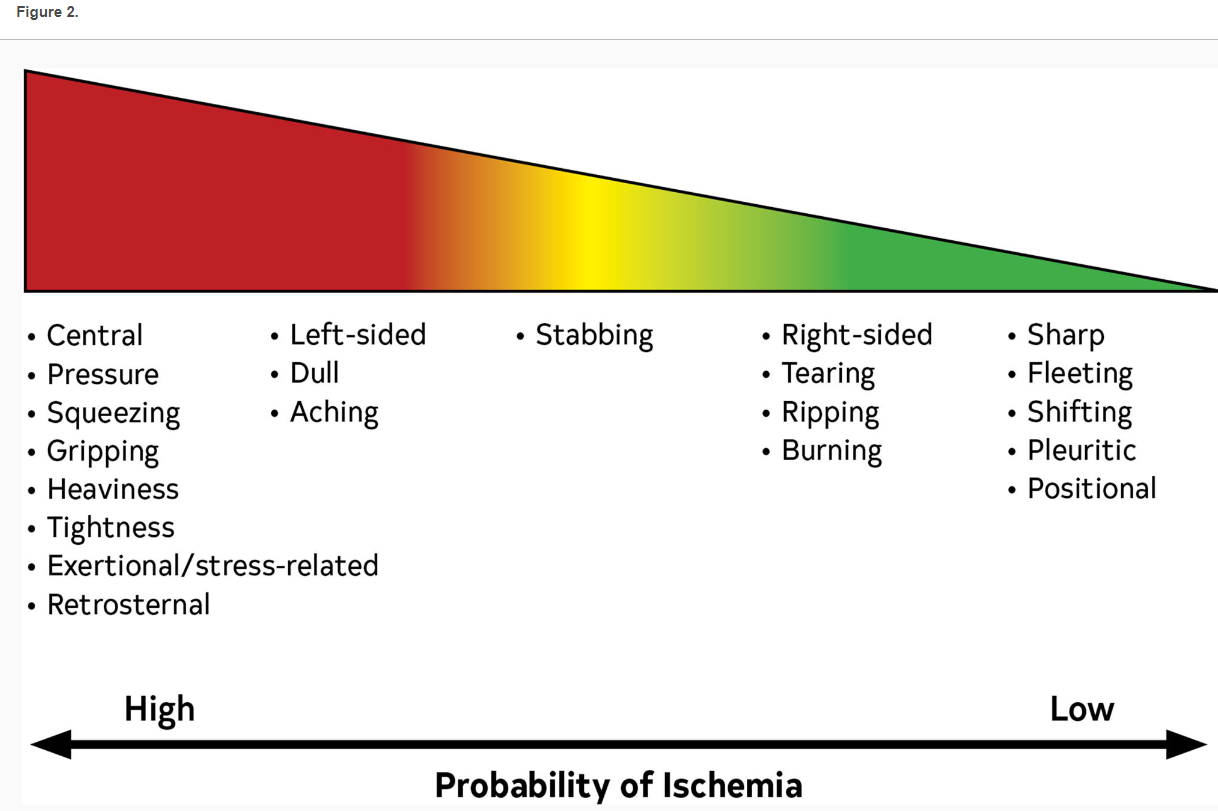

Chest pain is one of the most common reasons that people seek medical care. The term “chest pain” is used by patients and applied by clinicians to describe the many unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations in the anterior chest that prompt concern for a cardiac problem. Chest pain should be considered acute when it is new onset or involves a change in pattern, intensity, or duration compared with previous episodes in a patient with recurrent symptoms. Chest pain should be considered stable when symptoms are chronic and associated with consistent precipitants such as exertion or emotional stress.

Although the term chest pain is used in clinical practice, patients often report pressure, tightness, squeezing, heaviness, or burning. In this regard, a more appropriate term is “chest discomfort,” because patients may not use the descriptor “pain.” They may also report a location other than the chest, including the shoulder, arm, neck, back, upper abdomen, or jaw.

2. Initial Evaluation

2.1. History

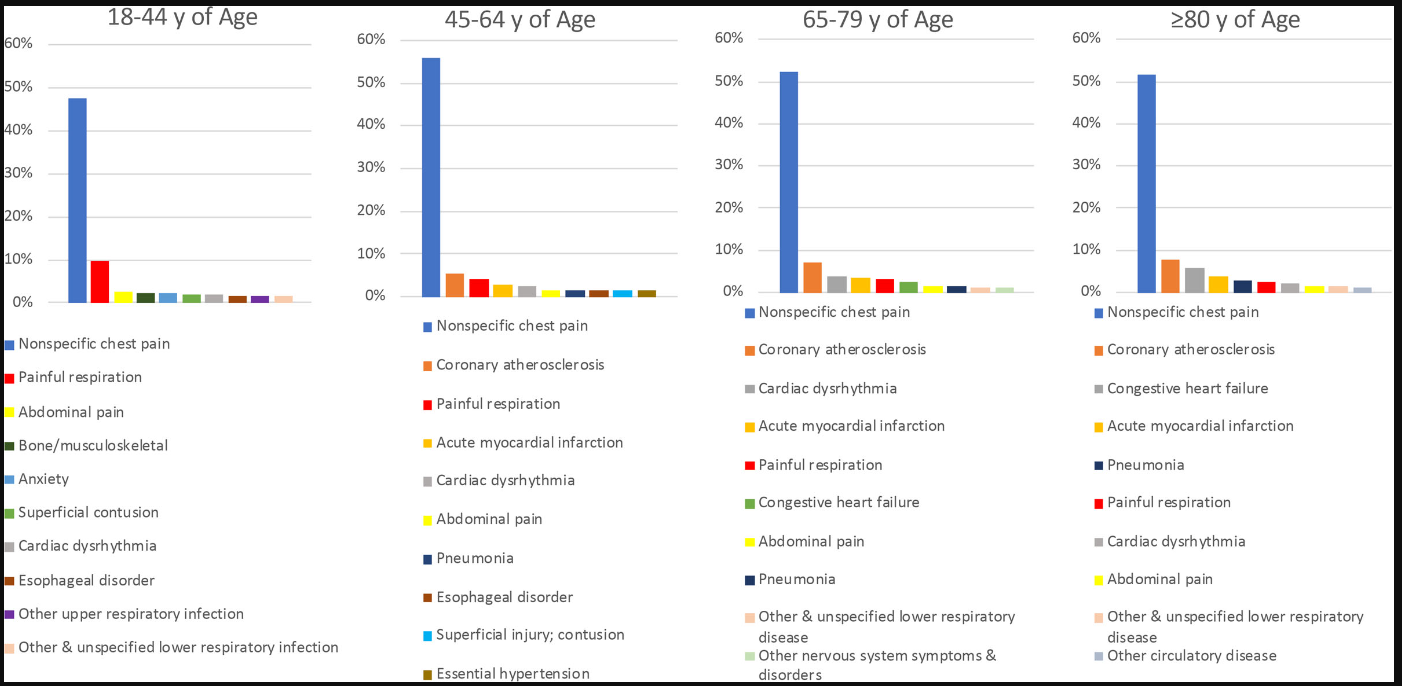

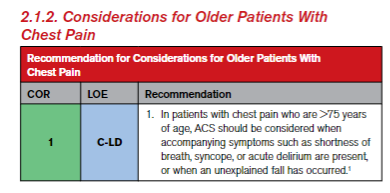

Figure 3 presents the top 10 causes of chest pain in ED based on age.

Figure 3. Top 10 Causes of Chest Pain in the ED Based on Age (Weighted Percentage) Created using data from Hsia RY, et al.7 ED indicates emergency department:

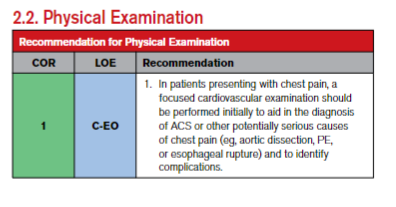

Table 3. Physical Examination in Patients With Chest Pain Clinical Syndrome Findings Emergency ACS Diaphoresis, tachypnea, tachycardia, hypotension, crackles, S3, MR murmur22; examination may be normal in uncomplicated cases PE Tachycardia + dyspnea—>90% of patients; pain with inspiration23 Aortic dissection Connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome), extremity pulse differential (30% of patients, type A>B)24 Severe pain, abrupt onset + pulse differential + widened mediastinum on CXR >80% probability of dissection25 Frequency of syncope >10%24, AR 40%–75% (type A)26 Esophageal rupture Emesis, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax (20% patients), unilateral decreased or absent breath sounds Other Noncoronary cardiac: AS, AR, HCM AS: Characteristic systolic murmur, tardus or parvus carotid pulse

AR: Diastolic murmur at right of sternum, rapid carotid upstroke

HCM: Increased or displaced left ventricular impulse, prominent a wave in jugular venous pressure, systolic murmurPericarditis Fever, pleuritic chest pain, increased in supine position, friction rub Myocarditis Fever, chest pain, heart failure, S3 Esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, gall bladder disease Epigastric tenderness

Right upper quadrant tenderness, Murphy signPneumonia Fever, localized chest pain, may be pleuritic, friction rub may be present, regional dullness to percussion, egophony Pneumothorax Dyspnea and pain on inspiration, unilateral absence of breath sounds Costochondritis, Tietze syndrome Tenderness of costochondral joints Herpes zoster Pain in dermatomal distribution, triggered by touch; characteristic rash (unilateral and dermatomal distribution)