In this post, I link to and excerpt from Autoimmune encephalitis: proposed best practice recommendations for diagnosis and acute management [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021 Jul;92(7):757-768.

There are 37 similar articles in PubMed Central.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

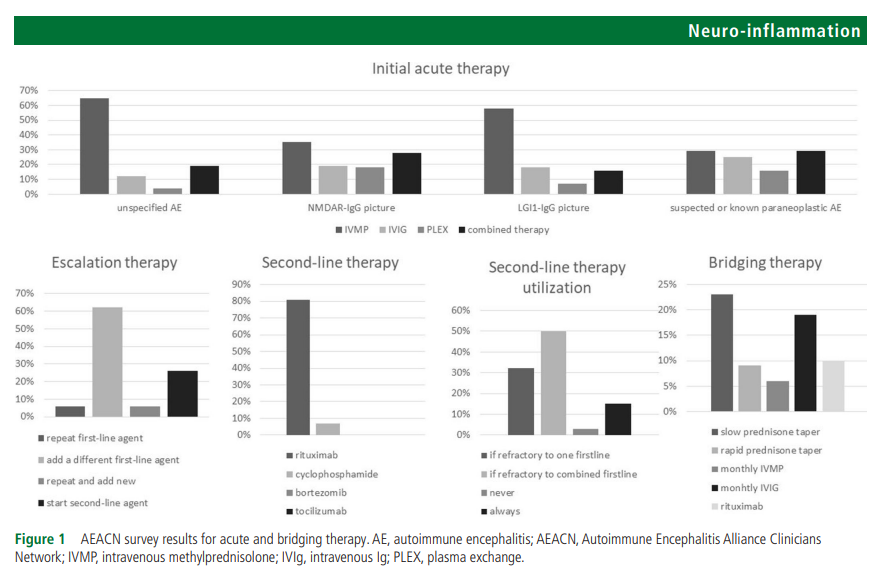

The objective of this paper is to evaluate available evidence for each step in autoimmune encephalitis management and provide expert opinion when evidence is lacking. The paper approaches autoimmune encephalitis as a broad category rather than focusing on individual antibody syndromes. Core authors from the Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance Clinicians Network reviewed literature and developed the first draft. Where evidence was lacking or controversial, an electronic survey was distributed to all members to solicit individual responses. Sixty-eight members from 17 countries answered the survey. Corticosteroids alone or combined with other agents (intravenous IG or plasmapheresis) were selected as a first-line therapy by 84% of responders for patients with a general presentation, 74% for patients presenting with faciobrachial dystonic seizures, 63% for NMDAR-IgG encephalitis and 48.5% for classical paraneoplastic encephalitis. Half the responders indicated they would add a second-line agent only if there was no response to more than one first-line agent, 32% indicated adding a second-line agent if there was no response to one first-line agent, while only 15% indicated using a second-line agent in all patients. As for the preferred second-line agent, 80% of responders chose rituximab while only 10% chose cyclophosphamide in a clinical scenario with unknown antibodies. Detailed survey results are presented in the manuscript and a summary of the diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations is presented at the conclusion.

Introduction

Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) comprises a group of non-infectious immune-mediated inflammatory disorders of the brain parenchyma often involving the cortical or deep grey matter with or without involvement of the white matter, meninges or the spinal cord.1–4 The original description of AE was based on paraneoplastic conditions related to antibodies against intracellular onconeuronal antigens such asANNA-1/anti-Hu.5 6 These ‘classical’ antibodies are non-pathogenic but represent markers of T-cell-mediated immunity against the neoplasm with secondary response against the nervous system. In recent years, an increasing number of antibodies targeting neuronal surface or synaptic antigens have been recognised such as N-MethylD-Aspartate Receptor (NMDAR)-antibody and Leucine-richglioma inactivated (LGI1)-antibody.1 Most of these surface antibodies have been shown to be likely pathogenic and are thought to mediate more immunotherapy-responsive forms of AE and have less association with tumours. Specific types of encephalitis can occur in the setting of antibodies against oligodendrocytes (eg, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) brainstem encephalitis) or astrocytes (eg, anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) diencephalic encephalitis, anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) meningoencephalitis). In addition, some AE patients do not have any identifiable antibodies (seronegative) representing a disease category with novel, yet to be identified antibodies or T-cell mediated disease. Online supplemental appendix S1 contains a list of the commercially available neuronal autoantibodies (NAAs).

Supplemental material

Recent epidemiological studies suggest that AE is possibly as common as infectious encephalitis with an estimated prevalence rate of 13.7/100 000.7 The rapidly advancing knowledge of new antibodies and their associated syndromes has created a new and growing field of autoimmune neurology.8 However, advances from the laboratory bench have not been paralleled by advancement in clinical practice, leading to a large knowledge gap and many unanswered questions regarding the acute and long-term management of AE. The heterogeneity of AE presentation and findings on ancillary testing hinder large-scale clinical trials and limit the quality of evidence behind AE management.

The objective of this paper is to evaluate available evidence for each step in AE management and provide expert opinion when evidence is lacking. Although the turnaround time of commercial NAAs panels may improve in the near future, currently these results are often unavailable at the time of early evaluation and management. Moreover, current commercial NAAs panels are inherently limited in their ability to diagnose AE, given the ever-growing numbers of antibodies identified and the likelihood of T-cell mediated pathogenesis in some cases. Consequently, clinicians have to approach AE initially as a clinical entity when deciding on investigations and treatment.1 Long-term management can then be modified according to the type of antibody identified, if any. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to emphasise the practical acute and long-term management of AE as a broad category rather than focusing on individual antibody syndromes. Another important goal is to represent the practice of experienced clinicians from different clinical and geographical backgrounds.

Survey results

The survey was distributed to 147 Clinical members. Sixty-eight (46%) members responded including the core authors. The most represented specialty/subspecialty of the respondents was neuroimmunology (66%), followed by general neurology (21%), paediatric neurology (16%), epilepsy (9%), behavioural/cognitive neurology (6%), hospital neurology-neurohospitalist (6%), neuromuscular neurology (6%), paediatric rheumatology (6%), neurocritical care (4%), psychiatry (4%), movement disorders (3%), general paediatrics (3%) and one specialist (1.5%) each of the following: autonomic disorders, adult rheumatology and paediatric critical care. Twenty-five members (37%) indicated more than one subspecialty.

Clinicians from 17 countries participated including USA (69%), Brazil (4%), Canada (3%), China (3%), Spain (3%), Argentina, Australia, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK (countries listed in a descending order based on the number of responders and alphabetically when the number of responders was equal). Of the total participating members, 88% practiced at academic tertiary referral centres and 76% were active in AE clinical research or scholarly publications. The participating members indicated personal clinical experience with an average of 7.3 AE subtypes (range 1–13 subtypes, median 8 subtypes). In total, 9% of the participating members were affiliated with reference neuroimmunology laboratories with NAAs testing capabilities. The results of individual survey questions are presented under the corresponding sections of AE management. The final draft was approved by all participating AEACN members after four rounds of revisions. The paper aimed to answer prespecified clinical questions as detailed below.

Data availability statement

The results of the survey are partially summarised in figure 1 and the detailed responses of all survey questions are published as online supplemental document 2.

Supplemental material

Section 1: diagnosis of AE

When to suspect AE clinically?

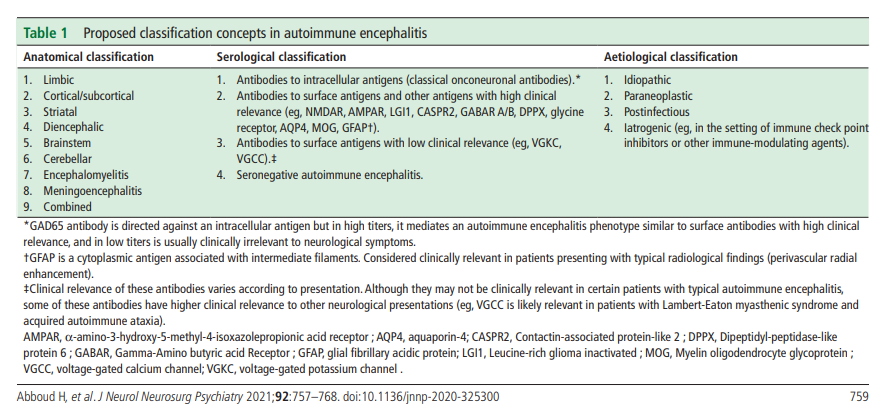

A detailed history and examination is the first and most important step in AE diagnosis. The immune reaction in AE often results in acute or subacute presentation of a duration less than 3 months.1 Chronic presentations are only seen in some of these conditions, especially LGI1, Contactin-associatedprotein-like 2 (CASPR2), Dipeptidyl-peptidase-likeprotein 6 (DPPX) and Glutamicacid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65)-antibody encephalitis, and should otherwise raise suspicion of a neurodegenerative disease or other etiologies.9 Likewise, hyperacute presentations are also atypical and a vascular aetiology should be considered in those cases. A recurrent course may point towards an autoimmune aetiology but unlike the typical relapsing-remitting course of multiple sclerosis and systemic inflammatory disorders, AE relapses are rare and often result from insufficient treatment or rapid interruption of immunotherapy. A monophasic course is more common in idiopathic AE while a progressive course may be seen in some paraneoplastic syndromes especially paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, which tends to plateau after the cancer is treated. Patients with known cancer or those at increased cancer risk (smokers, the elderly, and patients with rapid unintentional weight loss) are prone to paraneoplastic AE, while patients with personal or family history of other autoimmune disorders are at increased risk of idiopathic AE.10 A preceding viral infection, fever or viral-like prodrome is common.11 AE may be triggered by herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis or certain immune-modulating therapies such as TNFα inhibitors, and immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)—the latter can cause an accelerated form of paraneoplastic encephalitis in patients with advanced cancer.1 12 Table 1 shows practical classification concepts in AE.

Importantly, brain MRI can also help exclude alternativediagnoses such as acute stroke, neoplasm or Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD), although AE MRI changes can sometimes mimic some of these entities. Unilateral, and to a lesser extent bilateral, inflammation of the mesial and non-mesial temporal lobe as well as the orbitofrontal cortex on FLAIR or DWI sequences supports herpetic encephalitis over AE.13 Parenchymal haemorrhage on gradient echo sequence is more common in herpetic encephalitis than AE although this difference did not reach statistical significance in one underpowered study comparing the two types of encephalitis.14

In some related immune-mediated conditions, the diagnosis can be inferred from typical MRI patterns such as radial perivascular enhancement in autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy and punctate brainstem/cerebellar enhancement in chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS).15 16

The immune reaction in AE is usually diffuse, resulting in multifocal brain inflammation and occasionally additional involvement of the meninges, spinal cord and/or the peripheral nervous system.3 6 This diffuse inflammation may or may not be detectable on ancillary testing but it usually results in a polysyndromic presentation which is a clinical hallmark of AE. Although some antibodies have been linked to stereotypical symptoms (eg, oromandibular dyskinesia, cognitive/behavioural changes, and speech and autonomic dysfunction in NMDAR-antibody encephalitis, faciobrachial dystonic seizures in LGI1-antibody encephalitis, etc), there is significant symptom overlap between all antibodies and all forms of AE.1 11 Symptoms vary according to the anatomical localisation of inflammation and there are several clinical-anatomical syndrome categories in AE as summarised in table 2.

What investigations should be ordered when AE is suspected?

After AE is suspected clinically, a detailed workup is needed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude competing possibilities like infective encephalitis or systemic/metabolic causes. In most cases, the workup starts with brain imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. The diagnostic algorithm follows the structure summarised in figure 2 and detailed below:

Aim 1: confirming the presence of focal or multifocal brain abnormality suggestive of encephalitis

Aim 1: confirming the presence of focal or multifocal brain

abnormality suggestive of encephalitisBrain MRI

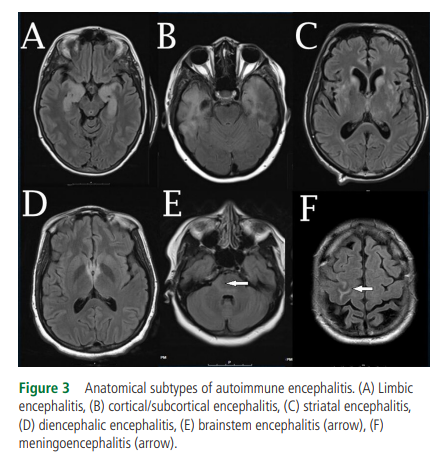

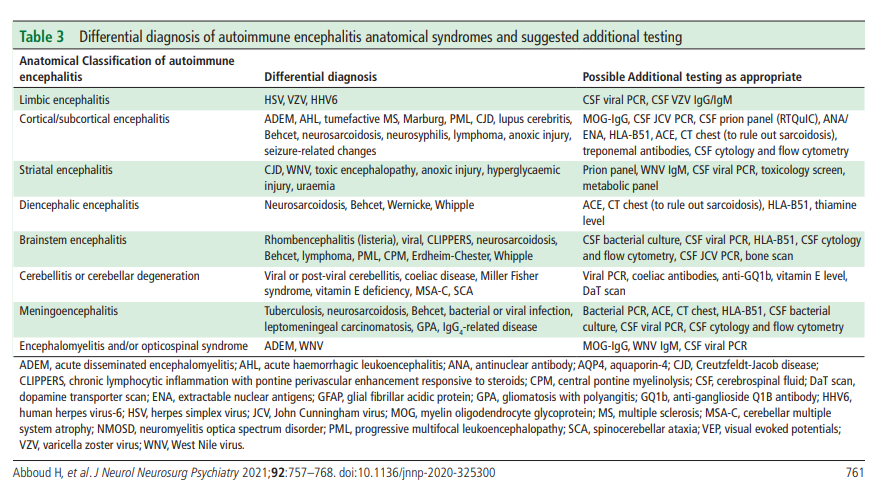

In addition to ruling out alternative diagnoses, standard Brain MRI with contrast can show changes consistent with one or more of the AE anatomical syndromes (table 1 and figure 3).

According to the 2016 AE clinical criteria by Graus et al, the presence of bilateral limbic encephalitis is the only MRI finding sufficient to diagnose definite AE in the correct clinical setting (eg, negative CSF viral studies) even in absence of NAAs.1

All other MRI patterns (cortical/subcortical, striatal, diencephalic, brainstem, encephalomyelitis and meningoencephalitis) can support possible or probable

AE unless the NAAs panel is positive for a clinically relevant

antibody.1 2 Diffuse or patchy contrast enhancement suggestive of inflammation is seen in a few patients while intense

enhancing lesions are unlikely in AE.3 9 Rare findings include

focal or extensive demyelination, meningeal enhancement, and rarely cortical diffusion restriction (often related to secondary seizures). Brain MRI may also be normal. Patients with initially negative MRI may show changes suggestive of AE on repeat MRI a few days later. Gadolinium should be avoided during pregnancy. Table 3 shows the main differential diagnoses for each of the AE anatomical syndromes.Importantly, brain MRI can also help exclude alternative diagnoses such as acute stroke, neoplasm or Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD), although AE MRI changes can sometimes mimic some of these entities. Unilateral, and to a lesser extent bilateral, inflammation of the mesial and non-mesial temporal lobe as well as the orbitofrontal cortex on FLAIR or DWI sequences supports herpetic encephalitis over AE.13 Parenchymal haemorrhage on gradient echo sequence is more common in herpetic encephalitis than AE although this difference did not reach statistical significance in one underpowered study comparing the two types of encephalitis.14

In some related immune-mediated conditions, the diagnosis can be inferred from typical MRI patterns such as radial perivascular enhancement in autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy and punctate brainstem/cerebellar enhancement in chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS).15 16

Electroencephalogram

Electroencephalogram (EEG) is commonly performed in patients with suspected AE to exclude subclinical status epilepticus in encephalopathic patients or to monitor treatment response in patients with seizures. AE is a major cause of new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE), which can be convulsive or non-convulsive.17 EEG can also provide evidence of focal or multifocal brain abnormality when MRI is negative which would support encephalitis over metabolic encephalopathy.1 Findings suggestive of AE include focal slowing/seizures, lateralised periodic discharges and/or extreme delta brush, which is occasionally seen in NMDAR-antibody encephalitis.18 Frequent subclinical seizures are commonly identified in LGI1-antibody encephalitis but patients may also have a normal EEG including those with classical faciobrachial dystonic seizures (FBDS).19 20 Although a normal EEG does not exclude AE, it can support primary psychiatric disorders when investigating patients with isolated new psychiatric symptoms. EEG can also help differentiate AE from CJD.