In this post, I link to and excerpt from Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text PDF]. Originally published14 Apr 2022https://doi.org/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000153Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2022;0:10.1161/ATV.0000000000000153

All that follows is from the above article.

Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an increasingly common condition that is believed to affect >25% of adults worldwide. Unless specific testing is done to identify NAFLD, the condition is typically silent until advanced and potentially irreversible liver impairment occurs. For this reason, the majority of patients with NAFLD are unaware of having this serious condition. Hepatic complications from NAFLD include nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition to these serious complications, NAFLD is a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which is the principal cause of death in patients with NAFLD. Accordingly, the purpose of this scientific statement is to review the underlying risk factors and pathophysiology of NAFLD, the associations with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, diagnostic and screening strategies, and potential interventions.

Keywords: AHA Scientific Statements; cardiovascular diseases; diabetes mellitus; hepatocytes; hypertriglyceridemia; insulin resistance; metabolic syndrome; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; triglycerides.

In the United States, the prevalence of NAFLD varies by race and ethnicity. Hispanic individuals have the highest prevalence rates, followed by White and Black individu-als (21%, 12.5%, and 11.6%, respectively).3,4 Risk among Hispanic people is not uniformly distributed among sub-groups. For example, in MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis), NAFLD prevalence among those of Mexican origin was 33%, but it was only 16% and 18% among those of Dominican and Puerto Rican origin, respectively.5

Accurate prevalence rates for NASH are difficult to approximate because diagnosis currently requires a liver biopsy for histology. In 1 study, among patients with NAFLD diagnosed by ultrasonography, biopsy-proven NASH was demonstrated in 19.4% of Hispanic and 9.8% of White patients (P=0.03).7 Among liver transplant donors, NASH prevalence rates vary from 1.4% to 15%.8–10 The estimated prevalence of NASH is 3% to 6%,11 with potentially higher rates among populations with the highest prevalence of NAFLD. Risk factors for NASH include type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity, all of which are prevalent. The prevalence of NASH in type 2 diabetes may exceed 37%.12 In a recently published study, 664 asymptomatic middle-aged American men and women with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30.5 kg/m2 (15% with type 2 diabe-tes) referred for colonoscopy were assessed for hepatic steatosis and liver stiffness by magnetic resonance and ultrasound imaging. Patients with abnormal imaging param-eters were offered liver biopsy. The prevalence of NAFLD in this cohort was 38%, and biopsy-confirmed NASH was identified in 14%.13

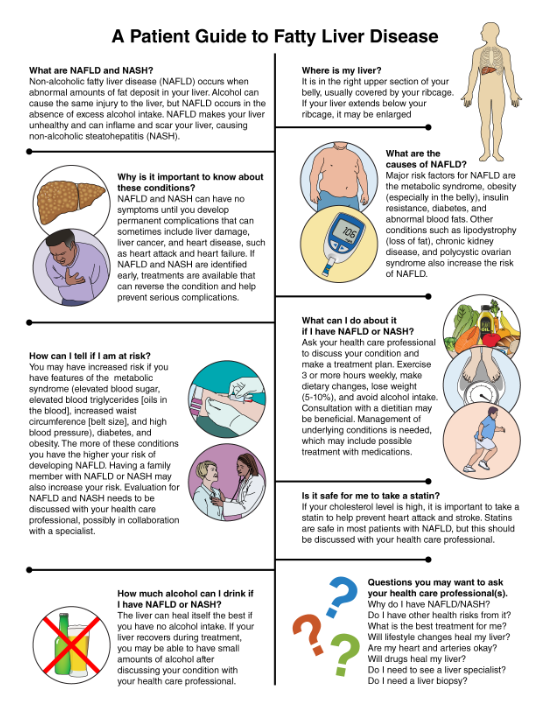

The purpose of this scientific statement is to succinctly highlight the pathophysiology, association with CVD, diagnostic strategies, and potential interventions for NAFLD. An informational handout about NAFLD was also developed for patient education.

KEY TAKE-HOME MESSAGES FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS1. NAFLD is common, occurring in >25% of individu-als worldwide, with rates increasing everywhere in association with rising rates of obesity and the metabolic syndrome.2. Most patients with NAFLD are undiagnosed. Measurements of AST and ALT are not useful for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH because of poor sensitivity and specificity. AST and ALT levels can be normal, even among patients with NASH. Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of NAFLD and NASH, but the procedure is expensive and has increased risk of complications. Noninvasive diag-nostic options such as vibration-controlled tran-sient elastography (FibroScan) are available but are underused.3. Most patients with hepatic steatosis do not prog-ress to develop NASH, cirrhosis, or hepatocel-lular carcinoma, but a subgroup will. It is difficult to identify which patients will have progression of disease, so imaging studies, possibly in combina-tion with liver biopsy, are essential for monitoring disease severity and progression. Routine hepatic ultrasonography is useful if it demonstrates hepatic steatosis, but it cannot quantify the extent of ste-atosis, nor can it rule out hepatic steatosis because of insensitivity of the technique.4. NAFLD occurs in association with insulin resistance, with or without diabetes, obesity (espe-cially visceral adiposity), metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia consisting of hypertriglyceridemia, increased free fatty acids, low high-density lipopro-tein cholesterol, and small dense LDL. Genetic fac-tors (monogenic or polygenic) modulate the risk of development of NAFLD and progression to NASH.5. NASH is an increasingly common cause of end-stage liver disease.6. NASH is a contributor to and marker for increased ASCVD risk. Many risk factors for NAFLD are also risk factors for ASCVD. A component of the increased risk of ASCVD in NAFLD is attributable to individual risk factors, but the presence of NAFLD is associated with increased ASCVD risk compared with individuals who have the same ASCVD risk factors without NAFLD.7. NAFLD can be considered a risk enhancer when ASCVD risk is assessed in patients.8. Lifestyle intervention is the key therapeutic inter-vention for patients with NAFLD. Dietary modifi-cation, increased physical activity, weight loss, and alcohol avoidance are strongly encouraged. Weight loss of 5% to 10% of body weight can reverse hepatic steatosis and stabilize or diminish NASH in many patients, but this goal is frequently diffi-cult to achieve. Improved insulin sensitivity, reduced hyperglycemia, and triglyceride lowering are additional goals of treatment.9. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists may modestly improve NAFLD in association with improved glycemia, weight loss, and reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.10. Novel experimental drug therapies that target vari-ous steps in the pathogenesis of NAFLD are in development, but most have modest efficacy, and toxicity has been a limiting factor for some agents.11. An informational handout about NAFLD is available for patient education (Below).

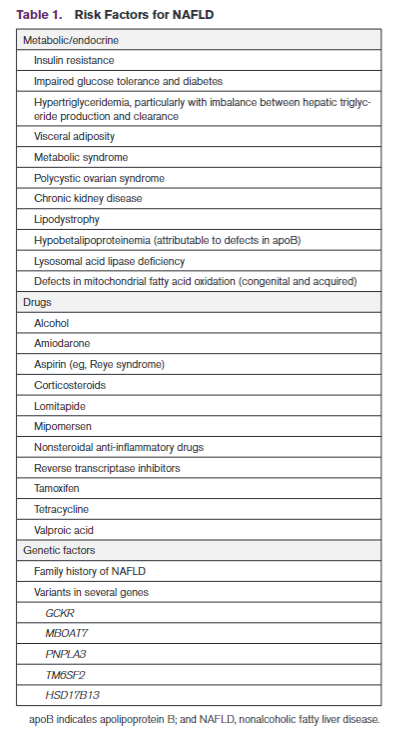

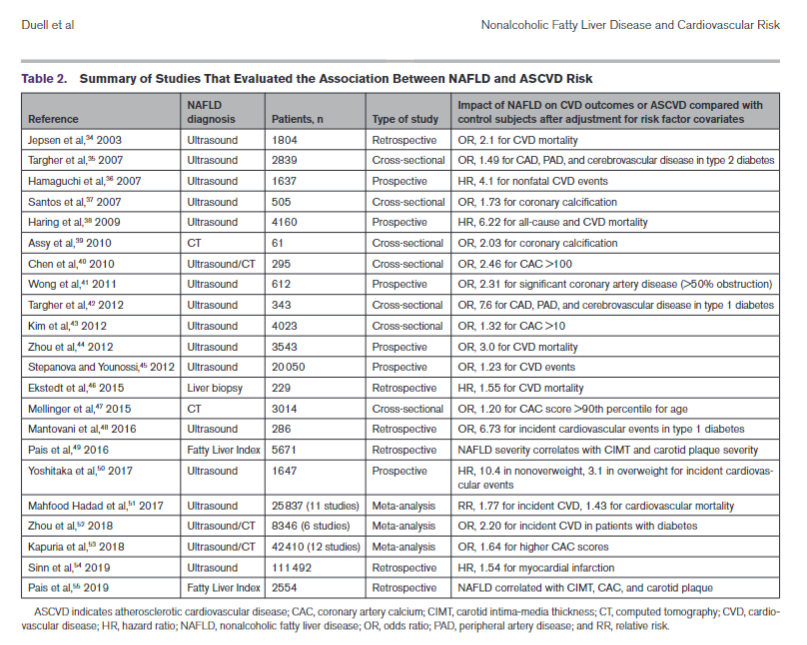

RISK FACTORS FOR NAFLDThere is overlap among risk factors for the metabolic syndrome and NAFLD, but patients can develop the metabolic syndrome without NAFLD and vice versa. Moreover, although a condition such as type 2 diabetes is associated with increased risk of NAFLD, the association is bidirectional, which means a diagnosis of NAFLD in a nondiabetic patient is associated with increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes. These interactions are related to the contribution of visceral adiposity and insulin resis-tance to the pathogenesis of NAFLD and type 2 diabe-tes. A summary of risk factors, including medications, is shown in Table 1.NAFLD AND ATHEROSCLEROTIC CVD RISKNAFLD is an underappreciated and independent risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) even after adjustment for ASCVD risk factor covariates in a large number of investigations (Table 2).34–55 Subclinical CVD and many other cardiovascular risk factors are increased among patients with NAFLD/NASH.56–58Risk factors for ASCVD are also increased by NAFLD; severity of NAFLD is associated with a higher incidence of ASCVD risk factors such as diabetes and hyperten-sion.59

STRATEGIES FOR SCREENING FOR NAFLD AND NASHA common misconception is that confirmation of normal plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) on routine laboratory testing is sufficient to exclude a diagnosis of NAFLD, but many patients with NAFLD have aminotransferase levels in the normal range, although frequently approaching the upper limit of normal. Moreover, hepatic ultrasonography is a relatively insensitive tool for identification of hepatic steatosis. As a consequence, many patients with NAFLD are undiagnosed or may be misdiagnosed as not having NAFLD. In some cases, patients may not be identified as having NAFLD until after they have progressed to NASH with cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease. Several strategies for identification of patients with increased risk or extant NAFLD have been developed. Because the definitive diagnosis of NAFLD is established on the basis of histological findings from liver biopsy, which is often unavailable, additional strategies have been developed to facilitate a tentative nonhistological diagnosis of NAFLD and to determine which patients warrant liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy is the definitive test for diagnosis of more advanced stages of NAFLD that include hepatic steatosis, NASH, and cirrhosis, but it is an expensive procedure that is associated with risk of morbidity and very low risk of death.83 Liver biopsy is not required in many patients but may be considered when the risk of advanced NASH is sufficiently elevated to war-rant liver biopsy or when liver biopsy is required to exclude other causes of liver disease. Consultation with a hepatologist is warranted.

Elevated NAFLD risk scores such as the NAFLD fibrosis score and fibro-sis-4 index score and evidence of fibrosis by liver stiff-ness measurement are potential indications for liver biopsy. The enhanced liver fibrosis score is based on plasma extracellular matrix protein biomarkers, has a high negative predictive value, and has been recom-mended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NAFLD guidelines as a potential additional tool for identifying patients who may benefit from liver biopsy.84,85 The presence of the metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes may lower the threshold for consider-ation of liver biopsy.

4. MRI. MRI is currently the preferred imaging modal-ity for quantitatively assessing NAFLD. It can reli-ably assess mild steatosis as well as moderate to severe grades. In 2 comparative studies, MRI sig-nificantly outperformed both ultrasound and CT imaging for detecting hepatic steatosis.92,93 MRI demonstrated a clear capacity to distinguish his-tological grades of steatosis, whereas ultrasound and CT did not.93 The sensitivity and specificity of MRI for hepatic steatosis are 76.7% to 90.0% and 87.1% to 81%, respectively.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONSNAFLD and NASH are increasingly common conditions that are underdiagnosed and underappreciated as risk factors for ASCVD morbidity and mortality. Improved diagnostic strategies for identification of NAFLD and NASH are needed, but existing modalities such as ultrasound-based vibration-controlled transient elas-tography (FibroScan) assessment of hepatic elasticity and steatosis are useful for disease staging and lon-gitudinal monitoring. A major gap exists in the treatment for NAFLD and NASH. Lifestyle modification that includes 5% to 10% weight loss, increased physical activity, and dietary modification is a key intervention, but further studies are needed to define optimal treat-ment strategies for the prevention of both hepatic and cardiovascular complications from NAFLD. Many exper-imental drugs with targeted mechanisms of action are in development, but toxicity has been an impediment for many. It is hoped that with increased awareness of NAFLD, better access to reliable imaging tools for screening and monitoring for NAFLD, and proven tools for the treatment of NAFLD, the rising tide of NASH and more advanced hepatic disease can be reversed and adverse ASCVD outcomes prevented.