Today, I reviewed, link to, and excerpt from the outstanding Neuropsychological Assessment in Dementia Diagnosis. [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Sandra Weintraub, PhD, ABCN/ABPP, FAAN. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2022 Jun 1; 28(3): 781–799. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001135

The above article has been cited by 3 articles in PubMed.

There are 112 similar articles in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above outstanding resource.

KEY POINTS

Abstract

Purpose of review:

This article discusses the application of neuropsychological evaluation to the workup of individuals with age-related cognitive impairment and suspected dementia. Referral questions, principles of evaluation, and common instruments to detect abnormalities in cognition and behavior in this population are reviewed. The integration of neuropsychological test findings with other clinical and biomarker information enhances early detection, differential diagnosis, and care planning.

Recent findings:

Life expectancy is increasing in the United States, and, accordingly, the prevalence and incidence of dementia associated with age-related neurodegenerative brain disease are rising. Age is the greatest risk factor for the dementia associated with Alzheimer disease, the most common neurodegenerative cause of dementia in people over 65 years of age; other etiologies, such as the class of frontotemporal lobar degenerations, are increasingly recognized in individuals both younger and older than 65 years of age. The clinical dementia diagnosis, unfortunately, is imperfectly related to disease etiology; however, probabilistic relationships can aid in diagnosis. Further, mounting evidence from postmortem brain autopsies points to multiple etiologies. The case examples in this article illustrate how the neuropsychological evaluation increases diagnostic accuracy and, most important, identifies salient cognitive and behavioral symptoms to target for nonpharmacologic intervention and caregiver education and support. Sharing the diagnosis with affected individuals is also discussed with reference to prognosis and severity of illness.

Summary:

The clinical neuropsychological examination facilitates early detection of dementia, characterizes the level of severity, defines salient clinical features, aids in differential diagnosis, and points to a pathway for care planning and disease education.

INTRODUCTION

In 1968, Blessed and colleagues2 published findings relating postmortem plaque counts to scores on a brief mental status questionnaire. This and other evidence linking Alzheimer neuropathology to cognitive loss argued strongly that dementia should be considered a disease and not a natural or obligatory outcome of the brain aging process. Katzman’s prophecy has come to pass; it has been estimated that the clinical syndrome of dementia occurs in 6% to 10% of the population older than 65 years of age, two-thirds due to AD pathophysiology.3 As lifespan in the United States and other developed countries increases, and as age constitutes the greatest risk factor for AD and related disorders, a concomitant increase will be seen in the incidence and prevalence of dementia.

The clinical syndrome of dementia (currently designated as major neurocognitive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5]6) is defined not only by the presence of cognitive and behavioral decline but also the degree to which this decline interferes with customary functional daily activities.

Before dementia, a patient’s cognition and behavior may be changing for many years but not to the extent that prevents an independent existence. During that time, the individual may remain productive and engaged, with appropriate support (Case 6-1).

A 71-year-old woman shared her concerns about memory loss with her primary care physician. She had been a librarian, and her physician, who had known her for 6 years, referred her for neuropsychological evaluation to assess baseline functioning given the patient’s past level of cognitive achievement and the absence of symptoms in routine screening. The patient had recently lost her spouse and was very tearful when describing her loss and the resulting void in her life. She had been prescribed an antidepressant, which she found helpful. She had no past history of depression, and her medical history was relatively benign except for elevated cholesterol, for which she took medication.

See the article for complete case.

Despite the marked limitation in her short-term retentive memory, scores on tests of reasoning were preserved and she did not report a significant level of depression or anxiety, despite mourning the loss of her spouse. A survey of activities of daily living9 completed by a relative disclosed very minimal changes in activities of daily living.

Her cognitive profile was marked by significant decline from expected levels in retentive memory and additional difficulties on tests of attention and semantic memory (ie, amnestic, multidomain profile). The clinical diagnosis was mild cognitive impairment,10 not dementia, because, by informant report, she was still independent in most activities of daily living.

She continued to be followed, and in 4 years, her symptoms had progressed to the point of severely limiting independence, and she required assistance in most complex activities of daily living. This represented both a decline in cognitive test performance and the emergence of difficulties in performing routine tasks. Based on worsening test scores and increased difficulty in activities of daily living, which now were in the severely impaired range, she was given a clinical diagnosis of dementia (major neurocognitive disorder). Because of the prominence of memory loss in the clinical profile, Alzheimer disease neuropathology was high on the list for differential diagnosis of etiology.4

COMMENT

This patient’s initial neuropsychological findings allowed her family to understand her level of impairment and begin making plans for care needs down the road. At that time, strategies for providing support for activities she eventually could no longer do (such as managing her finances) were built in, and accommodations to allow her to function maximally at her level were initiated in the form of calendars, checklists, telephone reminders, and someone to accompany her to doctors’ appointments. Despite the decline in neuropsychological test scores over time because of worsening disease, she continued to function with in-home assistance until her death 3 years later. A postmortem brain autopsy showed Alzheimer disease as the predominant neuropathologic finding.

Many dementia syndromes may begin with so-called atypical symptoms that may be attributed to peripheral organ changes (eg, eye problems) (Case 6-2) and misdiagnosed or go unrecognized until further progression occurs.

A 63-year-old man was referred for neuropsychological evaluation of a 4-year history of progressive visuospatial problems and difficulty acquiring new skills. Once when he was driving his car in the rain, he commented to his spouse that all he could see were the raindrops on the windshield. He was evaluated for visual acuity and was found to need mild correction with glasses; however, he continued to report “difficulty seeing.” Over time, his symptoms worsened, and he often bumped into objects in his path, misreached for objects within grasp, and could not “see” clothing in his closet, although it was in full view. A second visit to the ophthalmologist did not show evidence of changes in acuity. He had been having some challenges at his work as an accountant and was told that he might be experiencing excessive stress. His physician referred him for neuropsychological evaluation.

On examination, he had a perfect score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Despite this, his spouse reported that he had a moderate level of difficulty in executing routine daily tasks, including maintaining his personal belongings, and learning to use new devices, such as the new remote control for the television set. He was not able to manipulate the proper sequence of buttons and always held the controller in an awkward manner. In addition, his spouse reported the emergence of some behavioral changes on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q),11 largely in the form of apathy and irritability.

The profile derived from his test performance showed particular difficulty with visual attention and other visually based tasks, such as visual memory. Refer to the grid for his test scores and interpretation of the level of performance on tests of different domains by normative standards.

On the Trail Making Test, which is a test of executive attention, his performance was severely reduced not because of executive dysfunction but rather because he could not effectively search for the next item in the sequence. He had no difficulty judging angularity or copying a cube, but visual search in the absence of structure was challenging. Simultanagnosia was evident in his tendency to focus on only parts of an object. He was shown two pages, one of which contained a sentence written in 4-inch-high letters and a second with the same sentence in tiny letters. He immediately read aloud the small script but struggled with the large script, craning his neck and stepping back from the page. This indicated that when the visual image required successive eye movements, as with the large script, he could not “see,” but when the information was obtainable in a single fixation, it was easier for him.

See the article for details on the results of the neuropsychological tests.

COMMENT

This patient’s profile was one of progressive visuospatial dysfunction. This cognitive profile, also referred to as posterior cortical atrophy, is associated with occipitoparietal dysfunction and can be caused by Alzheimer neuropathology, cortical Lewy body disease, or corticobasal degeneration.12 Recommendations for care following the initial evaluation included home occupational therapy to ensure safety in the home and strategies for reducing the impact of visual limitations. The patient’s condition declined to the point that he was not able to continue caring for himself because of severe visual restrictions. As symptoms progressed, intervention strategies were initiated to help him adapt to the changes.

Although brain autopsy may disclose one predominant neuropathology in an individual with dementia, more often mixed pathologies are detected.5 AD is currently the best studied of the neurodegenerative causes of dementia, likely because of its prevalence; as a result, we now have in vivo biomarkers of its major protein abnormalities (ie, aggregated amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau) that can be detected in CSF or by specialized positron emission tomography (PET) scans using tau and amyloid ligands. Less invasive tests for plasma-based biomarkers, including neurofilament light chain, amyloid, and phosphorylated tau, are increasingly used predictively13–15 and, when broadly available, will have a significant impact on the diagnostic process. The emergence of amyloid-altering treatments calls for neuropsychological assessment before considering treatment to determine whether an individual has clinical symptoms of AD.

Biomarkers notwithstanding, however, increasing concern for dementia is causing individuals to seek evaluation when they subjectively sense a change from their baseline abilities. Interestingly, as cognitive symptoms increase, personal awareness decreases and observer awareness increases.16 In the prodromal or earliest stages of a dementia, especially in those with high prior levels of cognitive achievement and/or education, the routine screening accomplished with such tests as the Mini-Mental State Examination

(MMSE),17 the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),18 or the cursory bedside clinical mental status examination may yield no abnormalities. In those cases, it is important not to assume that cognition is normal but rather to escalate to a more rigorous

neuropsychological examination. In this case, the neuropsychological examination can detect subtle impairments, identify nonamnestic symptoms that are atypical for dementia

onset (eg, simultanagnosia), and, most important, provide a baseline against which longitudinal follow-up examinations can be compared to track progression. If cognitive screening test scores are in the impaired range, neuropsychological testing is also indicated since the examination provides an objective measure of the severity and characteristics of symptoms to use in care planning.19 In the event that the screening score indicatessubstantial cognitive impairment (eg, 10/30 on the MoCA or 13/30 on the MMSE), neuropsychological examination is likely to be too challenging for the patient, who in this

case would fail on every test, making the detection of a profile impossible. Even in severe cases, however, the neuropsychologist may choose to administer a brief set of appropriately tailored tests to pinpoint the primary area of deficit (eg, aphasia versus amnesia). In many instances, individuals may no longer be able to remain independent, and several ways to assess safety and decision-making capacity20 are available and can be added to the evaluation as required.THE CLINICAL NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

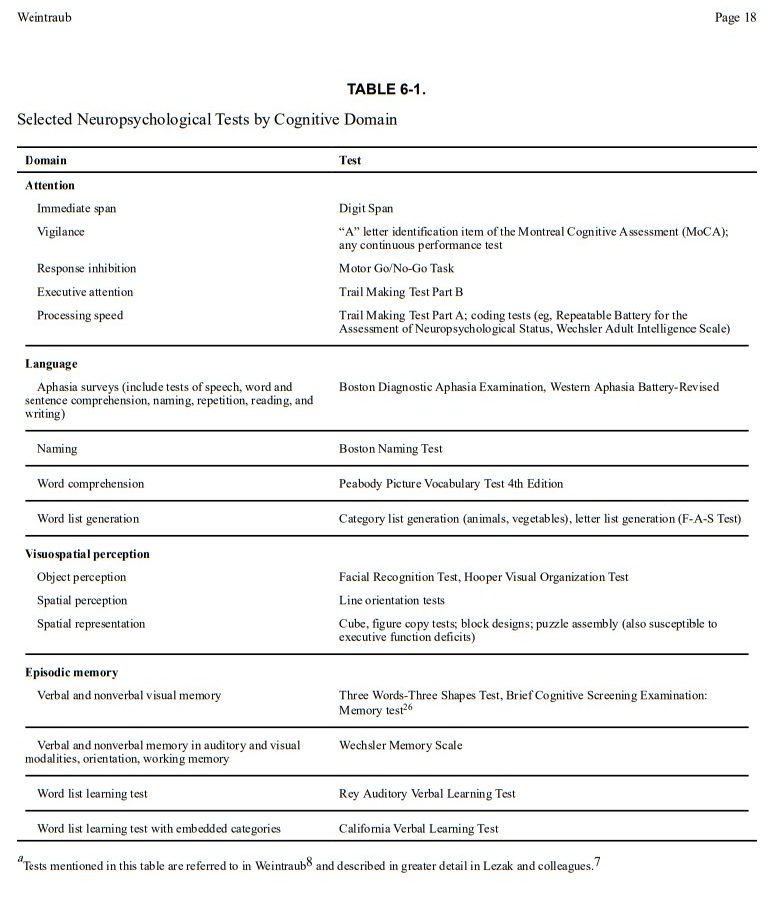

The examination itself consists of objective standardized tests of attention, language,

visuospatial perception, episodic memory, and executive functions (Table 6-1 26).

Each of these domains has been well studied in terms of the brain networks underlying them and how they are disrupted by neurologic disease. The scores obtained are compared with normative standards for the patient’s age, level of education, and other relevant demographics so that the level of functioning in each domain and the degree to

which it diverges from expectation can be quantified. Social cognition, also referred to as comportment or social-interpersonal skill, is commonly assessed through informant

interview and, in some cases, by objective measures.27 In addition to weighing the impact of education and experience on test performance, the neuropsychologist must also consider

whether medications or extant medical conditions could be contributing to test performance.Some common scenarios for considering referral for neuropsychological evaluation include the following:

Some common scenarios for considering referral for neuropsychological evaluation include the following:

History Taking

The neuropsychologist probes for evidence of a change from a person’s prior level of cognitive ability, character, and/or emotions and behavior. This is typically difficult to obtain because patients often do not recognize the changes. Even those who observe them may not accurately time the onset of symptoms, becoming aware of them only after a crisis. It is important to ask when patients last seemed like themselves in terms of carrying out routine activities, interacting with others, making decisions, and displaying typical emotional reactions (eg, sympathy, empathy). The key to detecting a dementia syndrome is change, not the specific symptom itself. Most individuals report a variety of cognitive symptoms as “memory loss.” Deeper probing can determine the neurocognitive domain within which the symptom really falls. For example, individuals with aphasia may report forgetting words, individuals with visuospatial deficits may report forgetting how to use common tools, and individuals with behavioral changes may report forgetting their manners. Table 6-2 lists some questions to use in history taking to elicit distinctive symptoms in a framework that is neurologically relevant for cognitive-behavioral neuroanatomic networks.

fig4when server ready.

The cognitive and behavioral functions surveyed in the examination are based on a model that relates complex cognitive functions to their underlying neuroanatomic and functional brain networks. Symptoms in domains such as language, spatial perception, visual object perception, social cognition, and episodic memory lend themselves to neuroanatomic network localization, whereas symptoms such as reduced arousal and attention are not easily localized in the same manner.8 The goal of the neuropsychological examination of an individual with suspected dementia, especially in the early stages, is to identify whether a single domain is involved (eg, episodic memory versus aphasia) or whether the patient has multiple cognitive and behavioral deficits. The early clinical profile (Figure 6-1) reflects the areas of the brain influenced by disease rather than the disease itself. Thus, aphasia as a predominant early symptom implies left-sided cerebral involvement in most right-handers and half of left-handers, whereas amnesia implies damage to medial temporal limbic areas.

fig5 when server ready.

The neuropsychological examination reviews attention, episodic memory, language, visuospatial functions, and executive abilities such as reasoning and set shifting. The interpretation takes into account how deficits in one domain can affect scores on tests in another domain, although that domain itself may be intact. For example, to establish that episodic memory is intact in the patient with word-finding difficulty, tests that will not be affected by the aphasia have to be used. The Three Words–Three Shapes Test was designed to compare verbal and nonverbal memory in the visual modality; the test can distinguish among different clinical dementia syndromes such as amnestic dementia (in which memory loss is paramount) and primary progressive aphasia (in which patterns of performance reflect the integrity of nonverbal episodic memory and recognition of verbal information that may not be retrievable spontaneously).29,30

Biomarkers have clearly been an advance in diagnosis, at least for AD. However, biomarkers do not provide information about the specific cognitive and behavioral symptoms an individual is experiencing, and these symptoms are not homogeneous across individuals with AD or other neurodegenerative diseases. Symptoms can differ vastly and need different interventions.

A BLUEPRINT FOR EDUCATION, SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT, AND MONITORING

The results of the neuropsychological examination are shared with the patient and support network as available, usually in the form of an in-person feedback session. During this session, the neuropsychologist reviews the findings and translates what they mean in terms of the individual’s experience, impact on daily living, and significance for diagnosis. It is important to explain the limits of knowledge based on the examination, that is, that the neuropsychological examination detects whether cognition or behavior is abnormal and specifies which functions are not normal but does not identify the disease causing the abnormality. An explanation of how brain regions implicated in disease are inferred by the test results provides patients with the knowledge that their symptoms reflect disease and are not the product of stress or lack of cooperation. This information also helps caregivers understand that neurologic limitations in the patient’s insight/awareness of illness makes it difficult for them to see reason, understand explanations, or even remember their diagnosis. In the course of feedback, the neuropsychologist can also explain how different diseases can cause dementia and that the biological nature of the disease rests on biomarker tests. It is important to explain that the pathophysiologic diagnosis still rests on biomarkers or postmortem brain autopsy, but the neuropsychological evaluation can give us probabilistic diagnoses.4 This helps caregivers understand why someone with a clinical diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia can be found to have AD or TDP-43 proteinopathy postmortem and that the initial clinical diagnosis is not in error.

CONCLUSION

Cognitive aging is heterogeneous, and not all decline is benign. With increasing recognition that age-related cognitive decline could imply future dementia, it is important for neurologists to obtain an objective measure of a patient’s cognitive function to inform the diagnosis, prognosis, and care recommendations. The clinical neuropsychological examination addresses issues that are not easily assessed in the cursory mental status examination or obtained in routine imaging and laboratory tests:

The neuropsychological examination can also document normal mental state in an individual with cognitive symptoms and then serve as a baseline against which future changes can be measured.