As usual, Emergency Medicine Cases has another outstanding podcast – this one is on the management of severe pediatric asthma.

Episode 79 – Management of Acute Pediatric Asthma Exacerbations (link is to the podcast and show notes) April 2016 from Emergency Medicine Cases.

Episode 79 Pediatric Asthma with Sanjay Mehta and Dennis Scolnik – This is a link to the PDF of the show notes for this podcast.

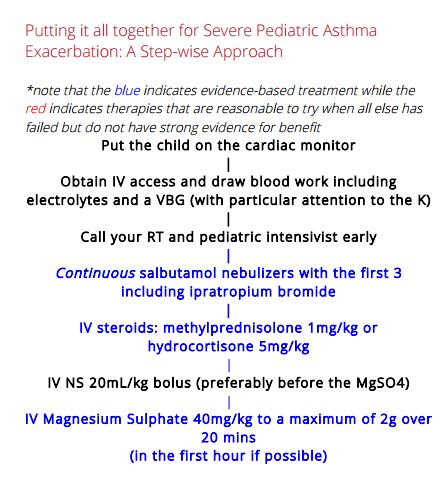

The following are excerpts from the PDF above. But the podcast and show notes contain much more than just these excerpts – as always this blog and podcast is just my own peripheral notes. So listen to the podcast and study the complete show notes. Here are the excerpts:

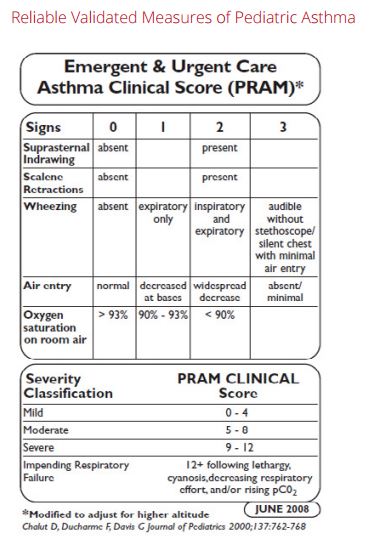

Pediatric Asthma Severity Indicators

- life-threatening exacerbations

- admissions to ICU

- intubation

- deterioration while already on systemic steroids

- using more than 2 canisters of short acting B-agonist per month

- cardiopulmonary and psychiatric comorbidities

Its important to realize that a lack of risk factors does not necessarily confer a lack of risk, so even if a patient has none of these risk factors, they can still be at risk for deterioration from their asthma.

VBG in Pediatric Asthma

A PaCO2 >42 is indicative but not diagnostic of a severe exacerbation

A PaCO2 >50 is a risk factor for impending respiratory failure

Metabolic Acidosis is an indicator of impending arrest!

A VBG is seldom indicated unless the child has no clinical improvement with maximal therapy. The timing of the VBG is important: It may be most useful as a baseline after ED treatment in a patient going to the ICU. Don’t forget the classic teaching: A ‘normal’ Hg partial pressure of CO2 in a patient with extreme tachypnea and retractions could indicate impaired ventilation and impending respiratory failure.

MDI vs Nebs vs IV B-agonists in Pediatric Asthma

Compared with nebulized treatments, metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a spacer use has been shown to be equally effective for children of all ages with a wide range of illness severity and by multiple outcome measures. . . . MDIs with a spacer should not be used in patients with impending respiratory failure and it can be difficult to coordinate breathing with administration of the inhaler for patients less than 1 year old.

IV beta-agonists have not been shown to be superior to inhaled beta-agonists. IV beta-agonists should be considered in those who are unable to tolerate nebulized or MDI treatments

For < 15 kg: Salbutamol MDI 4 puffs or 2.5mg nebulized in 2-3ml NS x3 back to back (continuously)

For > 15kg: Salbutamol MDI 8 puffs or 5mg nebulized in 2-3ml NS x3 back to back (continuously)

A Cochrane review found that those treated with continuously nebulized bronchodilators had lower rates of hospitalization, greater improvements in pulmonary function test results, and similar rates of adverse events compared with those treated intermittently.

Important Warning!

In children receiving multiple beta-agonist treatments, watch for hypokalemia, especially if the patient has diarrhea, or is on diuretic medications.

B-agonists with Ipatropium Bromide are more effective than B-agonists alone in Pediatric Asthma

So multiple doses of ipatropium bromide added to beta-agonists are indicated for kids with moderate to severe asthma exacerbations. However, there are no clinical trials supporting ipratropium use beyond the first hour or first 3 doses in children.

Ipatromium Bromide dosing: MDI 4 puffs (80mcg) or 250mcg nebulized

Single dose Dexamethasone is the preferred oral corticosteroid for Pediatric Asthma

So, it is reasonable to give one dose of dexamethasone at 0.3- 0.6mg/kg po to all but the sickest of kids who present to the ED with an asthma exacerbation, obviating the need for an outpatient prescription. It’s also worth noting that dexamethasone is associated with less vomiting compared to prednisolone as well.

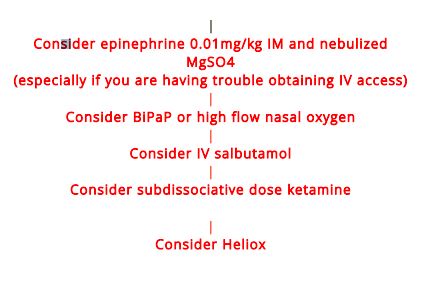

Intubation

The decision to intubate should be based on clinical judgement as opposed to any single vital sign or blood gas result. Some variables to consider for intubation are worsening hypercapnea, patient exhaustion and changes in mental status.