Today, I review, link to, and excerpt from Addiction Medicine’s #29 Hallucinogens with Dr. Al Garcia-Romeu.*

*Mullins KM; Garcia-Romeu A; Cohen SM; Sonoda K; Chan, CA. “#29 Hallucinogens with Dr. Al Garcia-Romeu”. The Curbsiders Addiction Medicine Podcast.https://thecurbsiders.com/addiction August 15th, 2024.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Aug 15, 2024 Addiction Medicine (Mini-series)Claim CME for this episode at curbsiders.vcuhealth.org!

By listening to this episode and completing CME, this can be used to count towards the new DEA 8-hr requirement on substance use disorders education.

The Curbsiders Addiction Medicine are proud to partner with The American College of Addiction Medicine (ACAAM) to bring you this mini-series. ACAAM is the proud home for academic addiction medicine faculty and trainees and is dedicated to training and supporting the next generation of academic addiction medicine leaders. Visit their website at acaam.org to learn more about their organization.

Show Segments

- Intro, disclaimer, guest bio

- Case from Kashlak; Definitions of hallucinogens and psychedelics

- Examples of hallucinogens and mechanisms of action

- Dosing strategies

- Risks of Use

- Psychedelic Assisted Therapy

- Outro

Hallucinogen Pearls

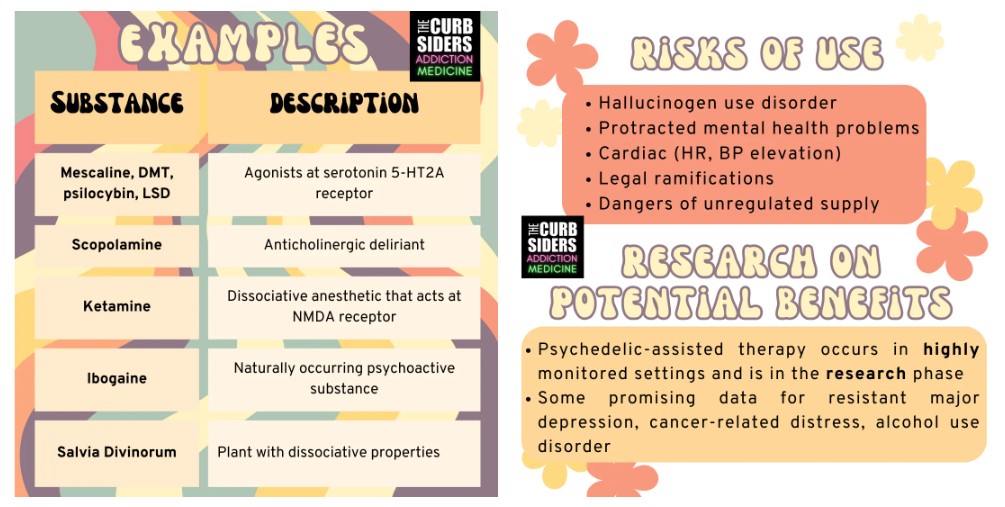

- Hallucinogens are a broad category of drugs that alter perception. Classic psychedelics that work through serotonin receptor agonism include mescaline, psilocybin, N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

- Microdosing hallucinogens has gained popularity in recent years, but evidence does not demonstrate any significant effect from this practice. The use of a single high dose of some hallucinogens has rapid-acting anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.

- Even though physical dependence to most hallucinogens is unlikely, hallucinogen use disorder exists and may be increasing in frequency.

- Risks of use include protracted mental health problems in certain at-risk individuals, elevated heart rate or blood pressure, and legal repercussions.

- Studies of therapeutic use differ from recreational use because they typically involve a structured therapeutic intervention, as well as weeks of preparation and integration.

Intro to Hallucinogens

Definitions

‘Hallucinogens’ are a broad category of drugs that induce perceptual changes, altered thoughts, and sensory distortions through diverse mechanisms of action. The term ‘psychedelic’ was coined in the 1950s by British psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond. Psychedelics classically includes the following compounds that work at least partially through serotonin receptor agonism (Halbertstadt 2015):

Examples and Mechanisms of Action

Mescaline: Naturally occurring in cacti such as peyote.

Psilocybin: An alkaloid produced by ~ 200 species of fungi in the psilocybe genus.

N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT): Present in various plants and animals, including ayahuasca.

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): A semi-synthetic compound.

The exact categorization and definitions are matters of expert opinion. Other hallucinogens include scopolamine (an anticholinergic deliriant), ketamine (a dissociative anesthetic that acts at the NMDA receptor), nitrous oxide (a dissociative anesthetic at certain doses), salvia divinorum (a plant with dissociative properties), and ibogaine (a naturally occurring psychoactive substance).

“Microdosing:” the practice of taking small, “sub-perceptual” doses of hallucinogens with the hope of producing some mental health benefit. Evidence at this time is limited (this is a challenging practice to study) and does not clearly suggest any significant effect (Polito 2024).

“High Dose:” a single high dose of some hallucinogens (psilocybin is currently one of the most well-studied) administered in conjunction with a therapeutic process has rapid-acting antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. Studies have supported this effect in resistant major depression (Goodwin 2022) and cancer-related existential distress (Griffiths 2016, Ross 2016) in particular.

Research also suggests a potential benefit for patients living with substance use disorders, including opioid use disorder (Savage 1973) and alcohol use disorder (Bogenschutz 2022).

Risks of Hallucinogen Use

Hallucinogen Use Disorder

Generally, psychedelic use and public interest have increased dramatically in the past few years (Patrick, 2022). Hallucinogen use disorder is listed in the DSM-V and may be increasing in frequency (Singh 2021), but remains uncommon compared to other substance use disorders (Shalit 2019). Psychologic dependence can occur, and physical dependence is unlikely for a few reasons. The first is tachyphylaxis, where the brain experiences a rapidly diminishing response to repeated doses until the drug has no effect at all (Nichols 2016). The second is the absence of a withdrawal syndrome for many hallucinogens. Since the effects tend to be long-lasting, these drugs also do not lend themselves to casual use on a regular basis. There is a documented recent increase in ketamine use disorder, but little is known about its treatment (Roberts 2024).

Health Risks of Use

Some people experience protracted mental health problems after use. It is difficult to predict who is at risk, but a personal or family history of psychosis or bipolar disorder may confer a higher risk (Simonsson, 2023). These drugs can also raise heart rate and blood pressure. There is a theoretical risk of valvular heart disease with chronic use due to activation of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor (Tagen 2023).

Legal and Practical Risks

Dr. Garcia-Romeu reminds us that most of these substances are illegal, so possession or use could have significant legal consequences. Most are currently Schedule 1 substances, so use is illegal by federal law without a research license. The illicit market also means that the supply is unregulated, so consumers can’t guarantee what they are taking (Leas 2024). Up to a third of products marketed to have psilocybin, did not contain any of that substances, but rather a synthetic drug called 4-ACO-DMT (SFGate).

Psychedelic Assisted Therapy

The Research Setting

Use in therapeutic contexts differs from recreational use in several key ways. It is important to note that Indigenous cultures were using these substances as part of their spiritual lives long before Western cultures started to try to fit them into a scientific framework.

Current clinical trials typically involve a three to four-week process leading up to drug administration involving intensive screening, intensive counseling, or structured therapy, often combined with psychoeducation. Different dosing models have been developed but are typically spaced out by at least a week or longer and may last for eight hours. High doses are used, and rescue medications are often available in case of agitation or dysphoria. All of this is followed by integration, an aftercare experience involving a debrief of what the person has experienced, including regular check-ins, typically for a number of weeks after the experience. Dr. Garcia-Romeu reports there is still a lot to learn on what the best type of therapy is to use in these different settings.

Public Access and Other Settings

A few of these substances may be in the pipeline to be considered for FDA approval based on the research (for instance, MDMA for the treatment of PTSD), but the time course remains unclear (Reiff 2020). In the meantime, recruiting clinical trials are available at clinicaltrials.gov.

In the case of ketamine, many variations of clinics with different degrees of medical or therapeutic oversight exist, which presents a challenge to consumers since the ways that ketamine is administered vary widely. For the field in general, Dr. Al cautions about the hype and media interest that may serve to distract us and our patients from the science.

Links

- ClinicalTrials.gov (list of clinical trials)

- Hopkins Psychedelic Lab

.