The following are excerpts from Resource (1) below:

Introduction: The purpose of this guideline is to establish clinical practice recommendations for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults, when such treatment is clinically indicated. Unlike previous meta-analyses, which focused on broad classes of drugs, this guideline focuses on individual drugs commonly used to treat insomnia. It includes drugs that are FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia, as well as several drugs commonly used to treat insomnia without an FDA indication for this condition. This guideline should be used in conjunction with other AASM guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of chronic insomnia in adults.*

*See Resources below after the excerpts for these citations.

Methods: The American Academy of Sleep Medicine commissioned a task force of four experts in sleep medicine. A systematic review was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials, and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) process was used to assess the evidence. The task force developed recommendations and assigned strengths based on the quality of evidence, the balance of benefits and

harms, and patient values and preferences. Literature reviews are provided for those pharmacologic agents for which sufficient evidence was available to establish recommendations. The AASM Board of Directors approved the final recommendations.Recommendations: The following recommendations are intended as a guideline for clinicians in choosing a specific pharmacological agent for treatment of chronic insomnia in adults, when such treatment is indicated. Under GRADE, a STRONG recommendation is one that clinicians should, under most circumstances, follow. A WEAK recommendation reflects a lower degree of certainty in the outcome and appropriateness of the patient-care strategy for all patients, but should not be construed as an indication of ineffectiveness. GRADE recommendation strengths do not refer to the magnitude of treatment effects in a particular patient, but rather, to the strength of evidence in published data. Downgrading the quality of evidence for these treatments is predictable

in GRADE, due to the funding source for most pharmacological clinical trials and the attendant risk of publication bias; the relatively small number of eligible trials for each individual agent; and the observed heterogeneity in the data. The ultimate judgment regarding propriety of any specific care must be made by the clinician in light of the individual circumstances presented by the patient, available diagnostic tools, accessible treatment options, and resources.[I have linked the name of each treatment drug to the monograph of that drug on Medscape Reference for the drugs recommended in the guidelines]

1. We suggest that clinicians use suvorexant [Belsomra] as a treatment for sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

2. We suggest that clinicians use eszopiclone [Lunesta] as a treatment for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

3. We suggest that clinicians use zaleplon [Sonata] as a treatment for sleep onset insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

4. We suggest that clinicians use zolpidem [Ambien, Ambien CR, and others] as a treatment for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

5. We suggest that clinicians use triazolam [Halcion] as a treatment for sleep onset insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

6. We suggest that clinicians use temazepam as a treatment for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

7. We suggest that clinicians use ramelteon*[Rozerem] as a treatment for sleep onset insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)*Ramelteon is a melatonin receptor agonist. See Therapeutic Effects of Melatonin Receptor Agonists on Sleep and Comorbid Disorders [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text PMC] [Full Text PDF]. Int J Mol Sci. 2014 Sep 9;15(9):15924-50. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915924.

The above has been cited in 12 PubMed Central articles.

8. We suggest that clinicians use doxepin [Silenor] as a treatment for sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK)

9. We suggest that clinicians not use trazodone as a treatment for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]

10. We suggest that clinicians not use tiagabine as a treatment for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]

11. We suggest that clinicians not use diphenhydramine as a treatment for sleep onset and sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]

12. We suggest that clinicians not use melatonin as a treatment for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]

13. We suggest that clinicians not use tryptophan as a treatment for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]

14. We suggest that clinicians not use valerian as a treatment for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (versus no treatment) in adults. (WEAK) [Emphasis Added]Introduction:

Pharmacotherapy is one of two major approaches to treatment, the alternative being cognitive behavioral therapies for insomnia (CBT-I)*, already identified as a standard of treatment. This paper does not directly address the relative benefits of these two approaches.

*See The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Cognit Ther Res. 2012 Oct 1; 36(5): 427–440.

The above has been cited by 194 articles in PubMed Central.

This clinical practice guideline is intended to serve as one component in an ongoing assessment of the individual patient with insomnia. As discussed elsewhere,5–7 a comprehensive initial evaluation should include a detailed history of sleep complaints, medical and psychiatric history, and medication/substance use. These factors, together with patient preferences and treatment availability, should be used to select specific treatments for specific patients. This clinical practice guideline is not intended to help clinicians determine which patient is appropriate for pharmacotherapy. Rather, it is intended to provide recommendations regarding specific insomnia drugs once the decision has been made to use pharmacotherapy.

This guideline should be used in conjunction with other AASM guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of chronic insomnia. These guidelines indicate that CBT-I is a standard of treatment and that such treatment carries a significantly favorable benefit:risk ratio. Therefore, based on these guidelines, all patients with chronic insomnia should receive CBT-I as a primary intervention. Medications for chronic insomnia disorder should be considered mainly in patients who are unable to participate in CBT-I, who still have symptoms despite participation in such treatments, or, in select cases, as a temporary adjunct to CBT-I.

Background

Insomnia disorder is defined in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition16 as a complaint of trouble initiating or maintaining sleep which is associated with daytime consequences and is not attributable to environmental circumstances or inadequate opportunity to sleep. The disorder is identified as chronic when it has persisted for at least three months at a frequency of at least three times per week. When the disorder meets the symptom criteria but has persisted for

less than three months, it is considered short-term insomnia.Occasional, short-term insomnia affects 30% to 50% of the population.17 The prevalence of chronic insomnia disorder in industrialized nations is estimated to be at least 5% to 10%.18,19 In medically and psychiatrically ill populations, as well as in older age groups, the prevalence is significantly higher. Chronic insomnia is associated with numerous adverse effects on function, health, and quality of life. Epidemiologic studies demonstrate marked impairment in functional status among those with chronic insomnia.20,21

PICO Questions

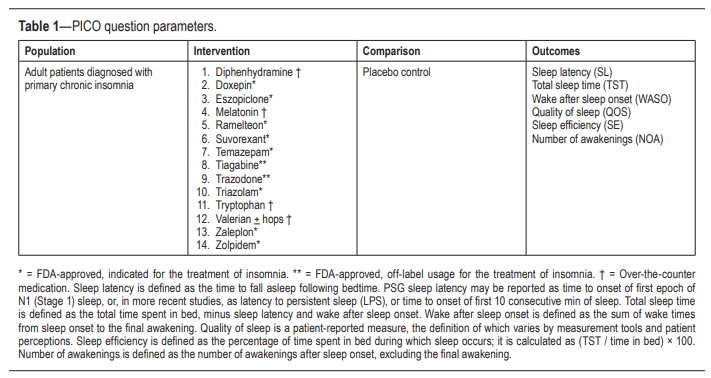

A PICO (Patient, Population or Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes) question template was developed to be the focus of this guideline:

“In adult patients diagnosed with primary chronic insomnia, how does [intervention] improve [outcomes], compared to placebo?”

The following outcomes were determined to be “critical” or “important” for clinical decision making across all interventions: sleep latency, wake after sleep onset, total sleep time, quality of sleep, number of awakenings, and sleep efficiency (Table 1).

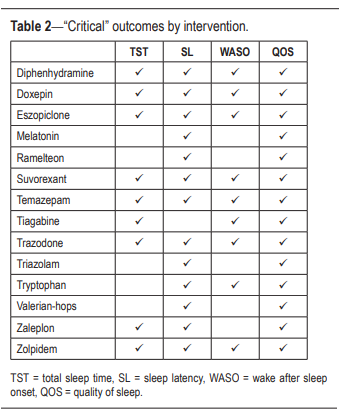

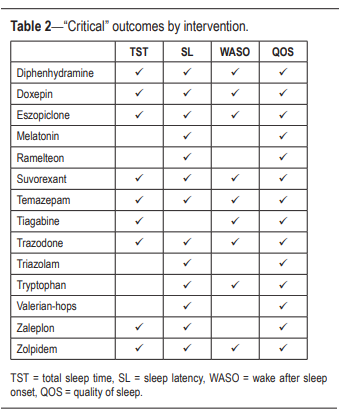

The task force then determined which outcomes

were “critical” for clinical decision making for each individual intervention (Table 2).

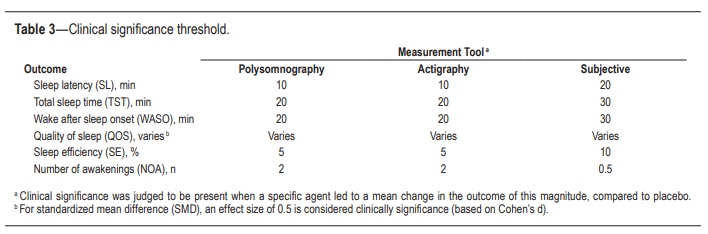

Lastly, clinical significance thresholds, used to determine if a change in an outcome was clinically significant, were defined for each outcome by task force clinical judgement, prior to statistical analysis (Table 3). These decisions were made by nominal consensus of the task force, based on their expertise and familiarity with the literature and clinical practice.

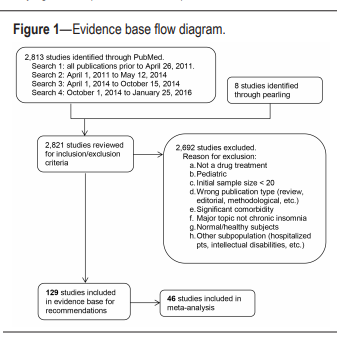

Literature Searches, Evidence Review and Data Extraction Multiple literature searches were performed by the AASM research staff using the PubMed database throughout the guideline development process (see Figure 1). Keywords and

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were:• insomnia OR sleep initiation and maintenance disorder NOT transient AND

• clinical trial OR randomized controlled trial

• NOT editorial, letter, comment, case reports, biography, review

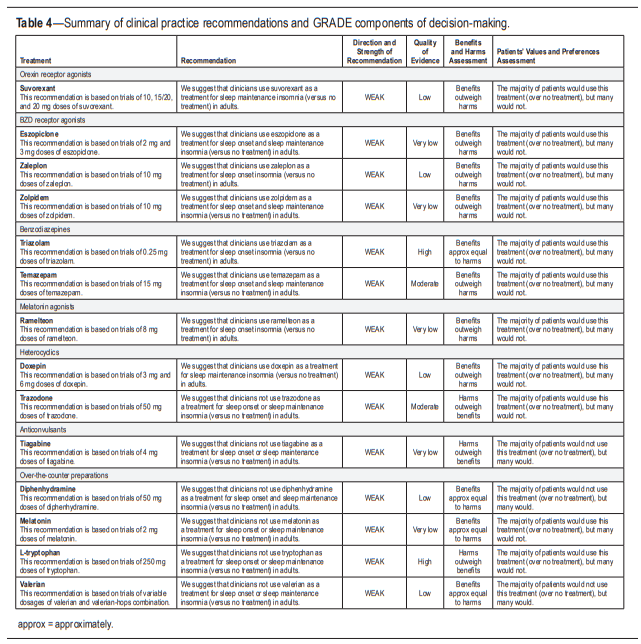

Clinical Practice Recommendations

The following clinical practice recommendations are based on the systematic review and evaluation of evidence following the GRADE methodology. Remarks are intended to provide context for the recommendations. All meta-analyses and summary of findings tables are presented in the supplemental material. A summary of the recommendations and GRADE determinations is presented in Table 4.

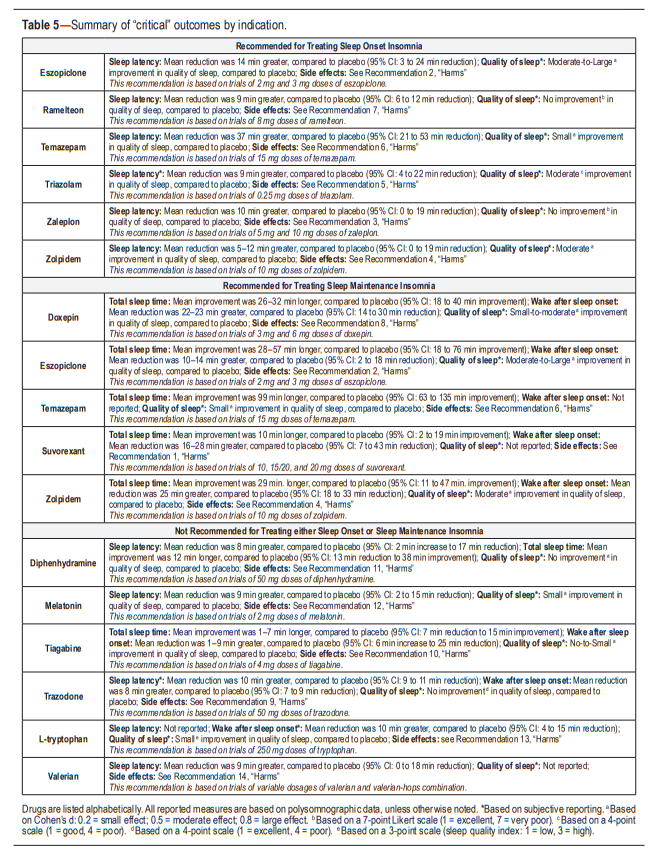

A summary of the recommendations,

“critical” outcomes, and side effects is presented in Table 5.

It is essential that the recommendations which follow be interpreted within the appropriate context of clinical practice. Readers will note that all specific recommendations fall within the “weak” (for or against) classification of the GRADE system. This should not be construed to mean that no sleep promoting medications are clearly efficacious or indicated in the treatment of chronic insomnia. Hypnotic medications, along with management of comorbidities and non-pharmacological interventions such as CBT, are an important therapeutic option for chronic insomnia. The strength of recommendations within the GRADE system are driven by the degree of confidence in a variety of factors related to the intervention including (1) the availability of specific data regarding efficacy; (2) the quality of that data, and (3) other considerations such as potential risks, impact of treatment, patient values and preferences, and perceived burden of treatment.

The strength (or weakness) of these recommendations speaks as much, or more, to the limitations of the data as it does to the relative benefits and risks of the treatments per se.

Clinicians must continue to exercise appropriate judgement, based not only on the recommendations presented herein, but also on individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and patient preferences in the prescribing of sleep-promoting medications and general management of chronic insomnia.

Detailed discussion of each of the medications summarized in Tables 4 and 5 are individually discussed in great detail on pp. 317 – 338.

There were medications for which clinical practice recommendations could not be made the data was inadequate for meta analyisis. These include:

- Estazolam

- Quazepam

- Flurazepam

- Oxazepam

- Quetiapine

- Gabapentin

- Paroxetin

- Trimipramine

Discussion And Future Directions

Defining “Efficacy”

Assessment of the efficacy of a given agent for the treatment of chronic insomnia is a complex and challenging task. It remains unclear which are the most important variables for defining efficacy.

In addition to the variability in outcome measures reported, there are a number of critical unresolved issues regarding evaluating the efficacy of treatments for chronic insomnia. One is the relative importance of subjective versus objective data. Another is whether metrics of sleep quality, whether they be subjective or objective (e.g. analysis of the microstructure of sleep or related physiological parameters), are perhaps more pertinent than measures of SL, TST or WASO.

An additional issue of importance is whether efficacy is better reflected by measures of daytime alertness and cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor function than by measures of sleep.

Recent behavioral treatment studies in chronic insomnia have taken yet another direction: measuring response or remission of the insomnia syndrome as the most clinically-relevant outcome.

This approach makes sense from a patient-centered approach, since most patients complain of “difficulty” falling asleep or staying asleep, rather than tying their complaints to any specific numerical value. Indeed, several studies have identified a group of “non-complaining poor sleepers” whose quantitative sleep measures are similar to those with insomnia. Examining the insomnia syndrome is also useful because it addresses both sleep-related and wake-related symptoms.Absent clear answers to these [the above] questions, the present analysis relies on conventional subjective and objective measures of major sleep variables (sleep onset latency, total sleep time or wake time after sleep onset).

The specific indications for use of a hypnotic employed in this report are limited to “sleep onset” and “sleep maintenance.” insomnia. We chose these since, from a practical clinical consideration, these are the primary complaints with which chronic insomnia patients present, and for which clinicians prescribe medication. Moreover, these are

the subtypes of insomnia that were actually studied in many investigations, consistent with FDA approval strategies and the matching of drugs to particular types of sleep disturbance.Hence, some medications may show substantial improvement in TST or sleep quality, yet demonstrate no or insignificant reduction in SL, WASO or NOA to qualify for a recommendation in favor of use.

Beyond the quality of evidence for or against use of a given drug for sleep onset or maintenance insomnia, the task force also considered the relative benefit:harm ratio and the likelihood that an informed patient would use a specific agent. To a

great extent, these decisions are based on clinical judgement.With respect to the benefit:harm consideration, the data on adverse events is often limited or non-existent. This may reflect the fact that treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) are typically not collected using specific assessment forms, but rather, rely on spontaneous reporting by research participants.

In addition, the frequency of some TEAEs is so low that the reported studies are underpowered to find a difference from placebo. This also implies that the effect size for a TEAE would be very small, and hence, it is unlikely that the clinical significance of TEAEs has been underestimated. However, some

TEAEs are very infrequent but very serious when they do occur (e.g. sleep-related behaviors with BzRA). Clinical trials are likely to underestimate such risks due to the limited number of patients treated and the limited duration of treatment. As a

result of these considerations, assessment of potential harms is largely derived from clinical experience and theoretical considerations, rather than well-documented evidence. This is clearly a limitation of the analysis and further, more systematic investigation of adverse effects is necessary.Clinical Application

Start here.

Resources

(1) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text PubReader] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15;13(2):307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470.

The above article has been cited by 49 PubMed Central articles.

(2) Practice parameters for the evaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Sleep. 2000 Mar 15;23(2):237-41

The above article has been cited 34 PubMed Central articles.

(3) Evaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text PDF]. Sleep. 2000 Mar 15;23(2):243-308.

The above article has been cited by 58 PubMed Central articles.

(4) Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15;4(5):487-504.

The above article has been cited by over 100 PubMed Central articles.

(5) Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 19;165(2):125-33. doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. Epub 2016 May 3.

The above article has been cited by over 100 PubMed Central articles.

(6) American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

The book is not available for free online. Here is a link to the Table of Contents. The book may be purchased online for $90.

Here is a link to the full text PDF from 2014 Chest – International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition: Highlights and Modifications.

The above article has been cited 89 PubMed Central articles.