The place to start is here at the link to the outstanding show notes and podcast Resource (1): #123 Sleep Apnea Pearls and Pitfalls from Dr. Barbara Phillips and The Curbsiders

NOVEMBER 5, 2018.

I’ve embedded the podcast because it is wonderful and is the resource to start with.

There are no excerpts from the above. Just review the show notes because they are perfect.

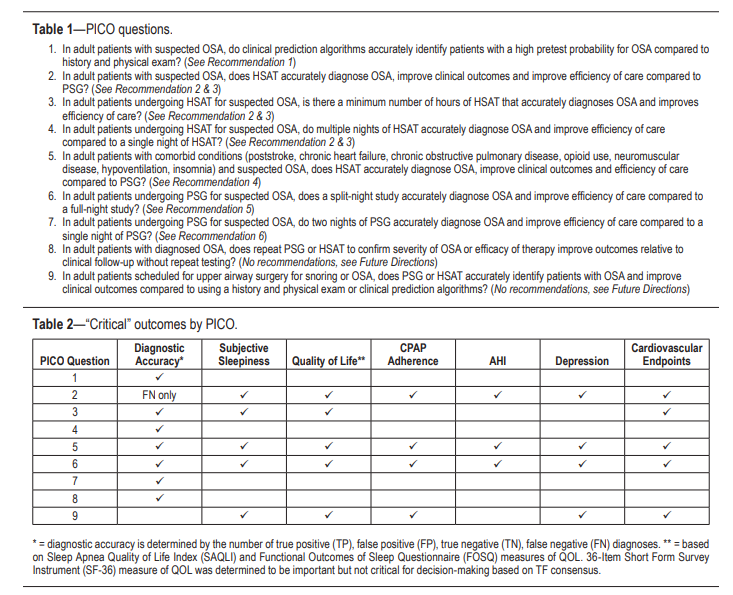

Resource (2) is the 2017 guideline for diagnostic testing for obstructive sleep apnea. Here is the link to the PDF.

It is to be noted that Dr. Phillips in the Curbsiders podcast above is not completely comfortable with all of the recommendations in the 2017 Guidelines. And some of the recommendations, which are based on very weak evidence, may increase cost to patients and reduce access.

Here are excerpts from Resource (2) below:

The term sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) encompasses a range of disorders, with most falling into the categories of OSA, central sleep apnea (CSA) or sleep-related hypoventilation. This paper focuses on diagnostic issues related to the diagnosis of OSA, a breathing disorder characterized by narrowing of the upper airway that impairs normal ventilation

during sleep. Recent reviews on the evaluation and management of CSA and sleep-related hypoventilation have been published separately by the AASM.3–5The prevalence of OSA varies significantly based on the population being studied and how OSA is defined (e.g., testing methodology, scoring criteria used, and apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] threshold). The prevalence of OSA has been estimated to be 14% of men and 5% of women, in a population-based study utilizing an AHI cutoff of ≥ 5 events/h (hypopneas associated with 4% oxygen desaturations) combined with clinical symptoms to define OSA.6 . . . In some populations, the prevalence of OSA is substantially higher than this estimate, for example, in patients being evaluated for bariatric surgery (estimated range of 70% to 80%)11 or in patients who have had a transient ischemic attack or stroke (estimated range of 60% to 70%).12

The third edition of the International Classification

of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) defines OSA as a PSG-determined obstructive respiratory disturbance index (RDI) ≥ 5 events/h associated with the typical symptoms of OSA (e.g., unrefreshing sleep, daytime sleepiness, fatigue or insomnia, awakening with a gasping or choking sensation, loud snoring, or witnessed apneas), or an obstructive RDI ≥ 15

events/h (even in the absence of symptoms).23 In addition to apneas and hypopneas that are included in the AHI, the RDI includes respiratory effort-related arousals (RERAs). The scoring of respiratory events is defined in The AASM

Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.3 (AASM Scoring Manual).24Due to the high prevalence of OSA, there is significant cost associated with evaluating all patients suspected of having OSA with PSG (currently considered the gold standard diagnostic test). Further, there also may be limited access to in laboratory testing in some areas. HSAT, which has limitations, is an alternative method to diagnose OSA in adults, and may be less costly and more efficient in some populations. This guideline addresses some of these issues using an evidence-based approach.

start here

Resources:

(1) #123 Sleep Apnea Pearls and Pitfalls [Link is to podcast and show notes.]

NOVEMBER 5, 2018 By Dr CYRUS ASKIN featuring Dr Barbara Phillips.

(2) Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Mar 15;13(3):479-504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506.

The above article has been cited 90 PubMed Central articles.

(3) Type I, Type II, Type III Sleep Monitors, CMS AASM Guidelines from the Cleveland Clinic, accessed 7-26-2019.

(4) Aurora RN, Chowdhuri S, Ramar K, et al. The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses. Sleep. 2012;35(1):17–40.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

(5) Berry RB, Chediak A, Brown LK, et al. Best clinical practices for the sleep center adjustment of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) in stable chronic alveolar hypoventilation syndromes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(5):491–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

(6) Aurora RN, Bista SR, Casey KR, et al. Updated adaptive servo-ventilation recommendations for the 2012 AASM guideline: “The Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea Syndromes in Adults: Practice Parameters with an Evidence-Based Literature Review and Meta-Analyses.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):757–761.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

(7) American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

24. Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications.Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2016. Version 2.3. [Google Scholar]