In addition to what follows below, please see Episode #61: Vasculitis and Giant-Cell Arteritis” – Awesome Help From The Curbsiders With Additional Resources

Posted on November 9, 2018 by Tom Wade MD

The following post contains excerpts from Resource (1) below, Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis [Pubmed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Aug; 82(970): 483–488:

Abbreviations: ESR, erthyrocyte sedimentation rate;

CRP, C reactive protein; ANCA, antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibody; p-ANCA, perinuclear ANCA;

ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; AAV, ANCA

associated vasculitides; IF, immunofluorescenceVasculitis means inflammation of the blood vessel wall. Any type of blood vessel in any organ could be affected. Clinical manifestations arise because:

- Systemic inflammatory response resulting from release of chemical mediators from inflamed blood vessels gives rise to various non-specific systemic manifestations. They include fever, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, arthralgia, myalgia and laboratory features such as normocytic and normochromic anaemia, leucocytosis, thrombocytosis, and raised erthyrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

and C reactive protein (CRP). Some patients, especially early in the course of their illness, could present with isolated systemic manifestations posing a diagnostic challenge. Conversely, systemic inflammatory response

is not seen in most patients with localised forms of vasculitis.- More specific manifestations from involvement of various organ systems arise from one or both of the following mechanisms1:

(1) Thinning of vessel wall due to inflammatory

cell infiltration: This leads to increased vascular permeability or vessel wall rupture. Haemorrhage occurs into the affected organ. Clinical presentation depends on site of involvement.

If only cutaneous venules are involved, red cell transudation or haemorrhage occurs within skin presenting with palpable purpura. If pulmonary capillaries are involved, presentation

could be more dramatic with haemorrhage occurring into alveoli presenting with breathlessness and haemoptysis.(2) Narrowing or complete occlusion of affected vessel because of vascular intimal proliferation and intraluminal thrombus formation: This leads to ischaemia or infarction of affected organs. Examples of presenting manifestations are necrotic skin ulcers, mononeuritis multiplex, or infarction of a major organ depending on site of involvement.

GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

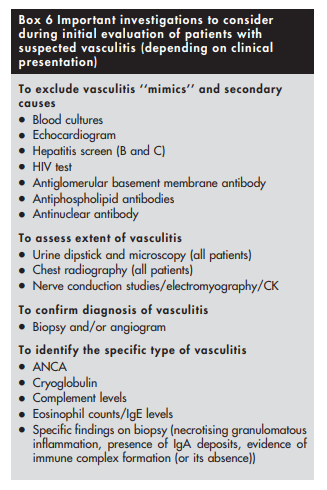

There are five important questions to ask when faced with a patient with possible vasculitis (depending on clinical presentation):

(1) Is this a condition that could mimic the presentation of vasculitis?

(2) Is there a secondary underlying cause?

(3) What is the extent of vasculitis?

(4) How do I confirm the diagnosis of vasculitis?

(5) What specific type of vasculitis is this?(1) Vasculitis ‘‘mimics’’ should be excluded first

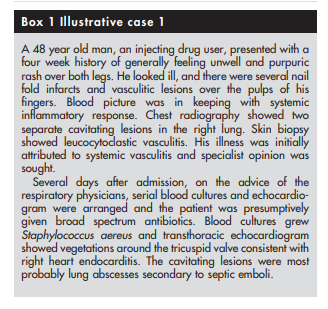

Several conditions could mimic vasculitis7–9 and need to be considered in the differential diagnosis depending on clinical presentation.

Firstly, infection is a great mimic of vasculitis

(see box 1).Several clinical and laboratory features are common to both vasculitis and infection. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia and weight loss, and laboratory features such as normocytic normochromic anaemia, peripheral blood leucocytosis, thrombocytosis, raised ESR, and CRP are encountered in both. Because treatment of vasculitis entails the use of immunosuppressive drugs, the consequences of not recognising infection would be disastrous. Thus, it is mandatory to perform a full and appropriate infection screen in all patients with suspected vasculitis especially those who present with systemic inflammatory features. It has been suggested that procalcitonin levels* are raised in patients with infection but not in those with non-infective inflammatory conditions,10 but this

test is not widely available.

* See Resource (2) below, 2017 Procalcitonin: a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis and antibiotic therapy for more on the use of Procalcitonin.

*And see also Resource (3) below, #25 Don’t perform Procalcitonin testing without an established, evidence-based protocol from Choosing Wisely: Twenty-Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question from the American Society For Clinical Pathology.

Apart from infection, several rare conditions including

thrombotic disorders such as antiphospholipid antibody

syndrome,11 thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, ,12 and sickle cell disease, embolisation from atrial myxoma13 14 and cholesterol emboli from atheroma,15 non-inflammatory vessel wall disorders such as fibromuscular dysplasia,16 amyloidosis, 17 and scurvy,18 and vasospasm due to ergot19 could all mimic presentation of vasculitis by causing ischaemic

manifestations or systemic symptoms.20

*See Resource (4) below, ARUP Consult – The Physician’s Guide to Lab Test Selection and Interpretation, for information on how to evaluate antiphospholipid syndrome, etc. [The above links are to Resource (4) topics.

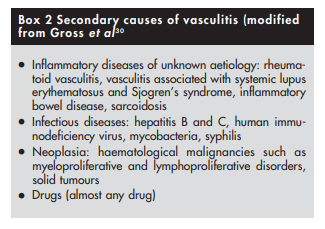

(2) Possible secondary causes of vasculitis should be excluded

Because treatment of some forms of vasculitis such as those that are secondary to infection or drugs is different from that of primary vasculitis, it is important to exclude such conditions that are likely to cause secondary vasculitis (box 2).

Infections often coexist with vasculitis, and some infections such as hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus, infective endocarditis, and tuberculosis are an important secondary cause of vasculitis.21,22,23,24,25 Presence of coexistent infection or an underlying infectious aetiology would change management of vasculitis. Immunosuppressive therapy that is used to treat patients with primary vasculitis could lead to disastrous consequences in the face of unrecognised infection. Thus, for example, patients with infected vasculitic leg ulcer should first receive appropriate antibiotic treatment to eradicate the infection before starting treatment for vasculitis, and those with polyarteritis nodosa secondary to hepatitis B infection should be treated with antiviral drugs and not cyclophosphamide.26

Most forms of secondary vasculitis are extremely rare with the possible exception of rheumatoid vasculitis.20 Vasculitis is seldom the initial presenting manifestation when it occurs in the setting of rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, and is thus readily diagnosed by features of the parent illness.

Among the secondary causes, drug induced vasculitis deserves special mention as resolution of vasculitis is likely to occur after withdrawal of the offending agent [Drug-induced vasculitis]. Patients could present with a wide range of manifestations ranging from isolated cutaneous vasculitis to widespread internal organ involvement. Drugs such as hydralazine, propylthiouracil, and montelukast have been implicated in the causation of ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) associated vasculitis. The ANCA is usually targeted against myeoperoxidase (perinuclear ANCA (p‐ANCA))28 (see below). Clinical presentation might be indistinguishable from idiopathic ANCA associated systemic vasculitides such as Wegener’s granulomatosis or Churg‐Strauss syndrome.29 A comprehensive drug history should therefore be obtained from all patients presenting with vasculitic manifestations.

(3) Extent of vasculitis should be assessed

It is important to assess the extent of vasculitis, and look for internal organ involvement even in patients who seem to have isolated cutaneous vasculitis. Both cutaneous leucocytoclastic angiitis and microscopic polyangiitis (see below) can present with palpable purpura, but while the first is usually a self limiting form of vasculitis that is often restricted to the skin, the second can be complicated by life threatening internal organ involvement.31

Extensive involvement and threat to vital organ function call for aggressive management.

A thorough history and detailed physical examination supplemented with a few simple investigations such as urine dipstick and chest radiography should be sufficient in most patients to assess extent of involvement with vasculitis.

(4) Histological and/or radiological proof of vasculitis should be obtained

Clinical evaluation should be focused towards identifying a suitable site for biopsy, as tissue diagnosis is vital to confirming the diagnosis of vasculitis. The site to be biopsied depends on clinical presentation. Common favoured sites include skin, kidney, temporal artery, muscle, nasal mucosa, lung, sural nerve, and testis.

Biopsy findings might sometimes not be helpful even in patients with definite vasculitis. Histological examination could be normal (yield with sural nerve biopsies in patients with definite vasculitis is only around 45%36) or show only non‐specific findings. For example, necrotising granulomas are not always seen in nasal mucosal or lung biopsy specimens from patients with suspected Wegener’s granulomatosis.37,38

If tissue diagnosis is impractical (patients with large or medium vessel vasculitis with no accessible tissue for obtaining histological proof), angiogram should be considered. For example, mesenteric and coeliac axis angiograms are useful in patients with suspected gastrointestinal tract vasculitis, while renal angiogram is useful in those with suspected renal artery involvement (not glomerulonephritis, which is best diagnosed with renal biopsy). Recently, computed tomographic angiography has been used to permit rapid diagnosis in patients with suspected polyarteritis nodosa.40 Characteristic angiographic findings in patients with medium vessel vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) include multiple microaneurysms (attributable to necrotising inflammation through vessel wall with consequent weakening).41 Magnetic resonance angiogram of the thoracic aorta is the investigation of choice in patients with suspected large vessel vasculitis such as Takayasu’s arteritis (see below).42,43 This would show stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm formation.

(5) The specific type of vasculitis should be identified (where possible)

Finally, it would be useful to identify the type of vasculitis, as

vasculitides with identical clinical presentation can have

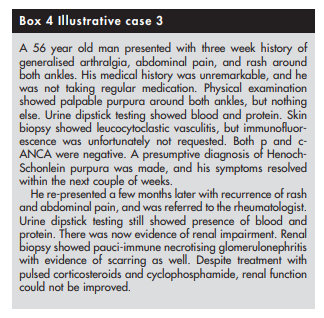

different prognoses. For example, Henoch-Schonlein purpura

and microscopic polyangiitis can both present with palpable

purpura and glomerulonephritis but prognosis is much better

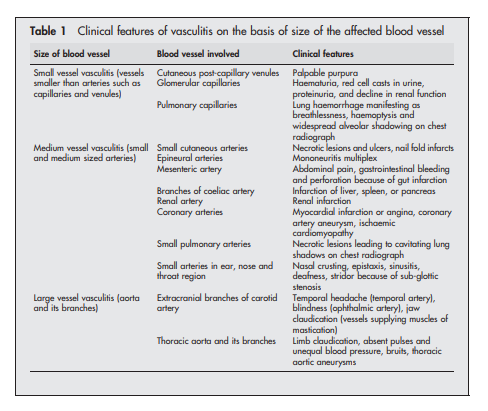

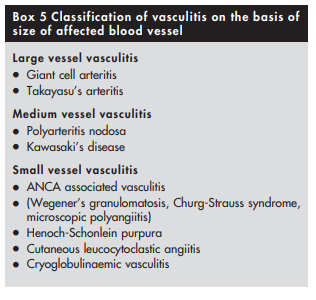

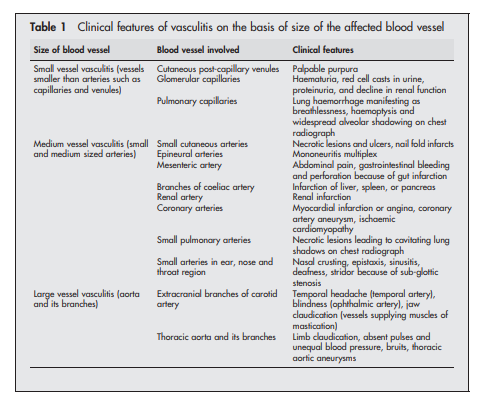

for patients with Henoch-Schonlein purpura44 45 (see box 4)The first step towards identifying the specific type of vasculitis is to categorise them according to the size of the affected vessel46 (see box 5 and table 1).

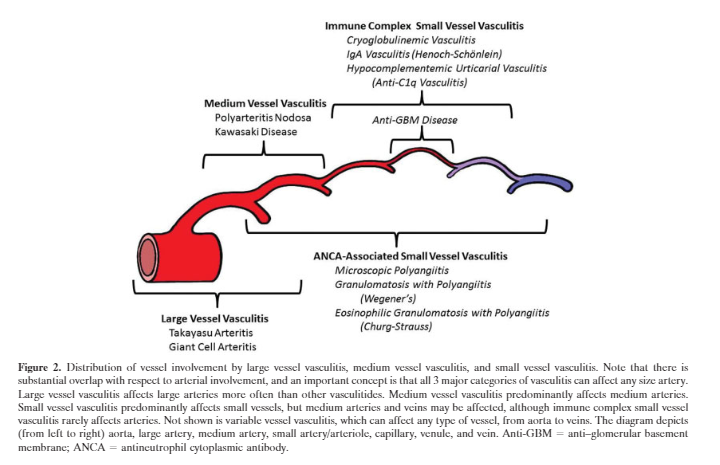

Here is the graphic from Resource (5):

Patients in whom large vessel vasculitis39 is suspected on the basis of involvement of aorta and its branches can then be labelled as either giant cell arteritis or Takayasu’s arteritis depending on their age, ethnic origin, and preference for involvement of specific blood vessels. Giant cell arteritis34 is probable in a white patient >50 years of age with preferential involvement of extracranial branches of the carotid artery, while Takayasu’s arteritis is probable in a Far Eastern patient <50 years of age with preferential involvement of thoracic aorta and its branches supplying upper limbs.

Polyarteritis nodosa is the prototype of medium vessel vasculitis. By definition, patients with small vessel involvement such as glomerulonephritis or pulmonary capillaritis should not be labelled as polyarteritis nodosa.47

Renal involvement can however still occur in polyarteritis nodosa because of hypertension or involvement of medium sized renal arteries leading to renal infarction.

Kawasaki’s disease48 is the equivalent of polyarteritis nodosa that occurs in young children. It is characterised by preferential involvement of coronary arteries leading to formation of coronary artery aneurysm and myocardial infarction.

Small vessel vasculitides are broadly subclassified on the basis of whether pathogenesis involves antibody mediated cytotoxicity or immune complex formation. It is particularly important to recognise those patients in whom vasculitis is likely to be caused by antibody mediated cytotoxicity, as they are prone to developing glomerulonephritis and (rarely) pulmonary capillaritis that require prompt treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. Absence of immune deposits on biopsy and presence of ANCA in serum can help to identify such patients. ANCA associated vasculitides (AAV) not only affect small vessels but also medium sized vessels such as arteries.

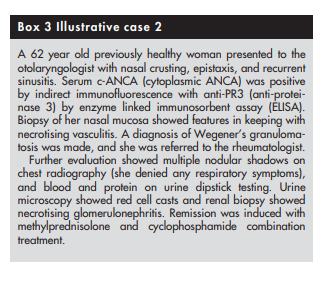

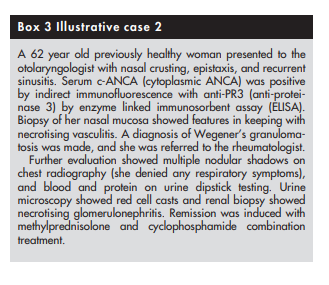

Two types of ANCA staining patterns are seen on immunofluorescence (IF), namely cytoplasmic (c‐ANCA) and perinuclear (p‐ANCA).49 ELISA should then always be performed in patients with positive results on immunofluorescence (IF) to identify the specific antigen targeted by ANCA. Presence of c‐ANCA with anti‐proteinase 3 (anti‐PR3) is highly suggestive of Wegener’s granulomatosis, while p‐ANCA with anti‐myeloperoxidase (anti‐MPO) is more often encountered in those Churg‐Strauss syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis.

Other forms of small vessel vasculitis (those that are immune complex mediated) could be identified by presence of other features. In a patient with joint pains, palpable purpura, abdominal pain, and nephritis, the presence of vascular IgA deposits on biopsy is diagnostic of Henoch‐Schonlein purpura. Presence of cryoglobulin in serum is suggestive of cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis. Cutaneous leucocytoclastic angiitis, which has an excellent prognosis, is a diagnosis of exclusion. Because histological examination of cutaneous leucocytoclastic angiitis is similar to that of dermal lesions occurring as a component of systemic small vessel vasculitides, it is important to exclude systemic disease in such patients.31

Conclusion

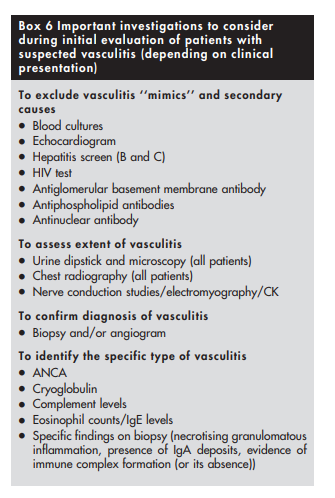

In summary, patients in whom vasculitis is suspected need detailed medical evaluation (box 6 above, near the beginning of this post). Because treatment of most primary forms of vasculitis consists of potentially toxic immunosuppressive therapy, exclusion of conditions that could mimic or cause vasculitis (especially infection and drug exposure) should take priority. Assessment of extent of disease, especially renal involvement, is equally important. Histological or radiological proof of vasculitis should be obtained, and where possible, the specific type of vasculitis should be identified. It is particularly important to recognise ANCA associated vasculitis in view of their poor prognosis and need for early treatment, but indiscriminate testing for ANCA in the absence of clinical evidence of vasculitis should be discouraged.

Resources:

(1) Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis [Pubmed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Aug; 82(970): 483–488.

The above article has been cited by 9 articles in PubMed Central.

(2) Procalcitonin: a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis and antibiotic therapy [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] . J Intensive Care. 2017 Aug 3;5:51. doi: 10.1186/s40560-017-0246-8. eCollection 2017

(3) #25 Don’t perform Procalcitonin testing without an established, evidence-based protocol from Choosing Wisely: Twenty-Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question from the American Society For Clinical Pathology.

Procalcitonin is a biomarker that has been used successfully to identify patients with certain bacterial infections (e.g., sepsis). The appropriate use includes serial (usually daily) measurements of procalcitonin in select patient populations (e.g. patients with fever and presumed serious infection for which antibiotics were initiated).(1) Such uses may help to identify low-risk patients with respiratory infections who would not benefit from antibiotic therapy, and to differentiate blood culture contaminants (e.g., coagulase-negative staphylococci) from true infections.(2,3) When used appropriately there are significant opportunities to decrease unnecessary antimicrobial use. The overuse of antimicrobial agents is directly related to the increasing antimicrobial resistance, so judicious use of these agents is warranted. Unfortunately, procalcitonin is often either misused (i.e. not used in the appropriate setting) or established algorithms are not followed. When the latter occurs, the procalcitonin result becomes simply another piece of laboratory data that adds costs, but does not benefit the patient. These

scenarios often occur because there is not an evidence-based utilization plan established at an institution. Laboratory and intensive care unit leadership are encouraged to identify the major users of procalcitonin, to establish guidelines that are most appropriate for the local setting and to monitor use.Assink-de Jong E. de Lange DW van Oers JA, et al. Stop Antibiotics on guidance of Procalcitonin Study (SAPS): a randomized prospective multicenter investigator-initiated trial to analyse whether daily measurements of procalcitonin versus standard-of-care approach can safely shorten antibiotic duration in intensive care unit patients – calculated sample size: 1816 patients. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013:13:178.

Rhee C. Using Procalcitonin to Guide Antibiotic Therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017:4:ofw249.

Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, et al. Use of Procalcitonin to Reduce Patients’ Exposure to Antibiotics in Intensive Care Units (PRORATA Trial): a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2010; 375:463-74.

(4) ARUP Consult – The Physician’s Guide to Lab Test Selection and Interpretation

ARUP Consult® is a laboratory test selection support tool with more than 2,000 lab tests categorized into disease-related topics and algorithms.

(5) 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1-11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715.

The above article has been cited by over 100 PubMed articles.

(6) Link To Comprehensive Rheumatology Review Of Systems and History Form From The American College Of Rheumatology

Posted on November 9, 2018 by Tom Wade MD

(7) EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 May;77(5):636-643. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212649. Epub 2018 Jan 22.

The above article has been cited by 12 articles in PubMed Central.