The purpose of this post is simply to remind me to consider autoimmune encephalitis in patients presenting to the office with even just subtle acute or subacute behavioral or acute mental status changes. And to move promptly to refer to the emergency department or neurologist if indicated.

The most important resource for primary care clinicians is actually Resource (3) Meningitis And Encephalitis article and podcast from The Internet Book Of Critical Care by Dr. Josh Farkas.

In addition, I’ve included three additional resources, (4) – (6), on other aspects of encephalitis.

This post consists of excerpts from Resource (1) below, A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis.

Abstract

Encephalitis is a severe inflammatory disorder of the brain with many possible causes and a complex differential diagnosis. Advances in autoimmune encephalitis research in the past 10 years have led to the identification of new syndromes and biomarkers that have transformed the diagnostic approach to these disorders. However, existing criteria for autoimmune encephalitis are too reliant on antibody testing and response to immunotherapy, which might delay the diagnosis. We reviewed the literature and gathered the experience of a team of experts with the aims of developing a practical, syndrome-based diagnostic approach to autoimmune encephalitis and

providing guidelines to navigate through the differential diagnosis. Because autoantibody test results and response to therapy are not available at disease onset, we based the initial diagnostic approach on neurological assessment and conventional tests that are accessible to most clinicians.

Through logical differential diagnosis, levels of evidence for autoimmune encephalitis (possible, probable, or definite) are achieved, which can lead to prompt immunotherapy.Introduction

Acute encephalitis is a debilitating neurological disorder that develops as a rapidly progressive encephalopathy (usually in less than 6 weeks) caused by brain inflammation.1 The estimated incidence of encephalitis in high-income countries is about 5–10 per 100 000 inhabitants per year; encephalitis affects patients of all ages and represents a significant

burden to patients, families, and society.2,3 Because the most frequently recognised causes of encephalitis are infectious, existing diagnostic criteria and consensus guidelines for encephalitis assume an infectious origin.1,4–6 However, in the past 10 years an increasing number of non-infectious, mostly autoimmune, encephalitis cases have been identified and some of them do not meet existing criteria.7 These newly identified forms of autoimmune encephalitis might be associated with antibodies against neuronal cell-surface or synaptic proteins (table)8–23 and can develop with core symptoms resembling infectious encephalitis, and also with neurological and psychiatric manifestations without fever or CSF pleocytosis.7

To improve the recognition of these disorders, in this Position Paper, we aim to provide a practical clinical approach to diagnosis that should be accessible to most physicians.These guidelines focus on autoimmune encephalitis that presents with subacute onset of memory deficits or altered mental status, accompanied or not by other symptoms and manifestations, with the goal of helping to establish a prompt diagnosis. These guidelines do not address the clinical approach to other CNS autoimmune disorders (stiff person syndrome,24 progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus,25 or autoimmune cerebellopathies26) that usually present with a clinical profile clearly different from autoimmune encephalitis.

Existing diagnostic criteria for autoimmune encephalitis are too reliant on antibody testing and response to immunotherapy.27 In our opinion, it is not realistic to include antibody status as part of the early diagnostic criteria in view of the fact that antibody testing is not readily accessible in many institutions and results can take several weeks to obtain. Furthermore, the absence of autoantibodies does not exclude the possibility that a disorder is immune mediated, and a positive test does not always imply an accurate diagnosis. Use of the response to immunotherapy as part of the diagnostic criteria is also not practical because this information is not available at the time of symptom onset or early clinical evaluation. Some patients with autoimmune encephalitis might not respond to immunotherapy or could need intensive and prolonged therapies that are not available in most health-care systems unless a firm diagnosis has been pre-established.28 Conversely, patients with other disorders might respond to immunotherapy (eg, primary CNS lymphoma).

The clinical facts and evidence suggesting that early immunotherapy improves outcome29–31 have been considered in the development of the guidelines presented here, in which conventional neurological evaluation and standard diagnostic tests (eg, MRI, CSF, or EEG studies) prevail in the initial assessment. This approach should allow the initiation of preliminary treatment while other studies and comprehensive antibody tests are processed and subsequently used to refine the diagnosis and treatment.

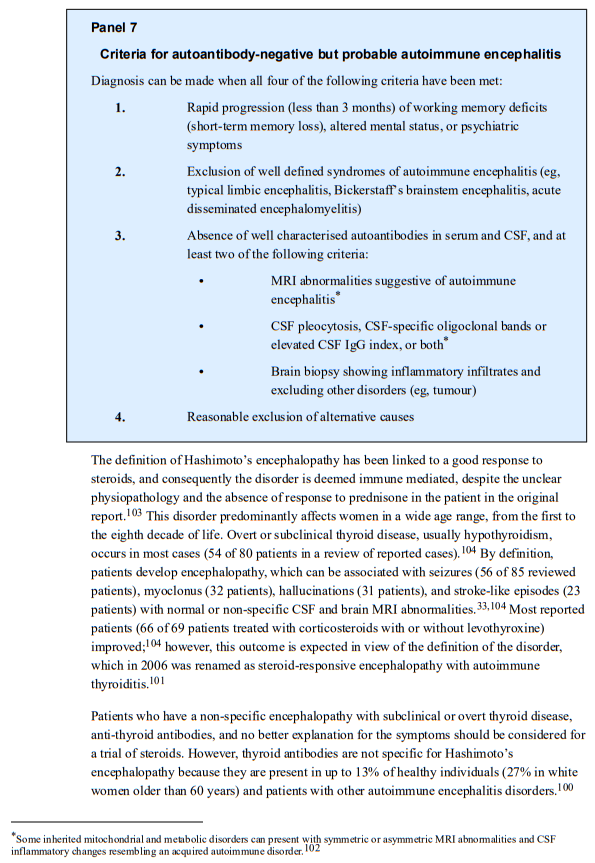

The above-mentioned focus of these guidelines and the initial approach based on conventional clinical assessment explain why some disorders are included in the main text and others are included in the appendix or excluded. As an example, we have included acute disseminated encephalomyelitis because the clinical presentation can be similar to that of other autoimmune encephalitis disorders.32 Another example is Hashimoto’s

encephalopathy, the existence of which is under discussion, but in practice is frequently listed in the differential diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis;33 thus, we believed it should be discussed, while emphasising the controversies and diagnostic limitations. By contrast, Morvan’s syndrome34 and Rasmussen’s encephalitis,35 which have a solid autoimmune

basis, are not included in the main text because they usually follow a more chronic course and the initial or predominant symptoms (peripheral nerve hyperexcitability, or focal seizures and unilateral deficits) are different from those mentioned above. We recognise the overlap that can occur between these disorders and autoimmune encephalitis and for this reason they are discussed in the appendix.Because children do not develop many of the autoimmune encephalitis disorders that affect adults, and the syndrome presentation might be different or less clinically recognisable,

these guidelines should be applied with caution in children, particularly in children younger than 5 years.36,37Initial clinical assessment: possible autoimmune encephalitis

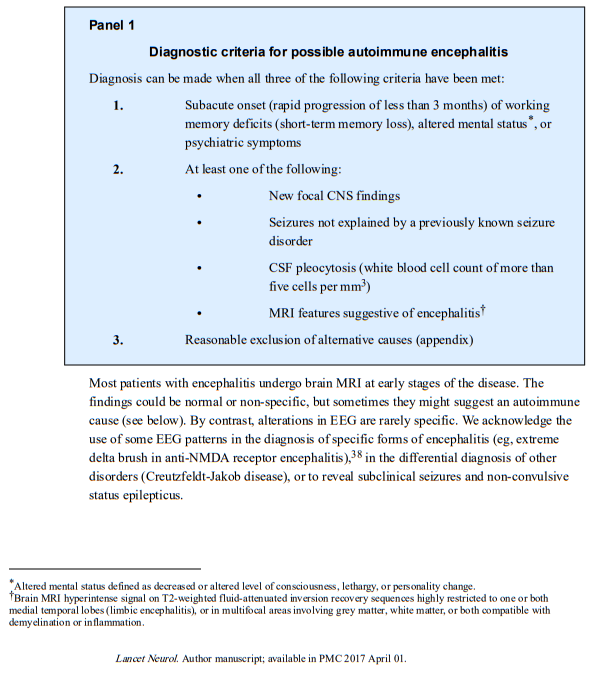

We regard a patient with new-onset encephalitis as having possible autoimmune encephalitis if the criteria shown in panel 1 are met.

These criteria differ from those previously proposed for encephalitis (any cause or idiopathic) in which changes in the level of consciousness, fever, CSF pleocytosis, and EEG alterations are more often needed.1,4–6 These criteria

needed to be adapted for autoimmune encephalitis because patients with autoimmune encephalitis could present with memory or behavioural deficits without fever or alteration in

the level of consciousness, or with normal brain MRI or CSF results.7 In this context, memory deficits refer to the inability to form new, long-term memories owing to hippocampal dysfunction, or problems with working memory, which refers to structures and processes used for temporary storage and manipulation of information.In addition to the above criteria, patients should be carefully examined for other diseases that can mimic autoimmune encephalitis and cause rapidly progressive encephalopathy

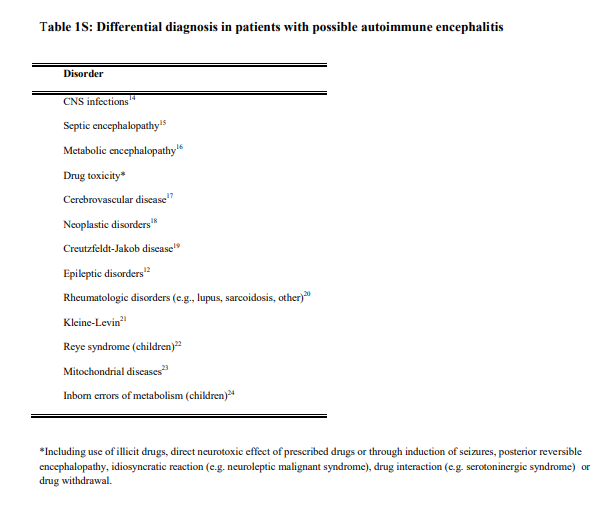

(appendix)* [Link is to the download of the appendix PDF].

*Table 1S from the Appendix:

Returning to excerpts from Resource (1):

These diseases should be excluded before immunotherapy begins and in most instances a detailed clinical history, complete general and neurological examination, routine blood and CSF analysis, and brain MRI including diffusion sequences will suffice to accomplish this goal. The most frequent differential diagnoses are herpes simplex virus encephalitis and other CNS infections. Importantly, CSF herpes simplex virus PCR can be negative if done too early (eg, within 24 h), and this test should be repeated if the clinical suspicion remains high.39 Previous reviews have addressed the differential diagnosis of

infectious encephalitis.1,40Approach to patients with clinically recognisable syndromes

A substantial number of patients with autoimmune encephalitis do not present with a well defined syndrome. In some of these patients, demographic information and some comorbidities (eg, diarrhoea, ovarian teratoma, faciobrachial dystonic seizures) might initially suggest the underlying disorder (anti-dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein-6 [DPPX], anti-NMDA receptor, anti leucine-rich, glioma-inactivated 1 [LGI1] encephalitis), but these

features are not pathognomonic and might be absent in some patients.11,41,42 In such cases, the diagnosis of definite autoimmune encephalitis greatly depends on the results of autoantibody tests. By contrast, disorders exist in which the clinical syndrome and MRI findings allow for classification as probable or definite autoimmune encephalitis before the autoantibody status is known. These include limbic encephalitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and other syndromes with MRI features that predominantly involve white matter, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, and Bickerstaff’s brainstem encephalitis (Figure 1).43

In addition I’ve included additional resources on encephalitis below.

Resources

(1) A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Apr;15(4):391-404. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9. Epub 2016 Feb 20.

The above article has been cited by over 100 articles in PubMed Central.

(2) Supplement to: Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of

autoimmune encephalitis [Download PDF]. Lancet Neurol 2016; published online Feb 19. https://dx.doi. org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9.

(3) Meningitis And Encephalitis article and podcast from The Internet Book Of Critical Care by Dr. Josh Farkas.

(4) Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults – Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. J Infect. 2012 Apr;64(4):347-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.014. Epub 2011 Nov 18.

The above article has been cited by 50 articles in PubMed Central.

(5) SUMMARY DOCUMENT: Management of Suspected Viral Encephalitis in Adults – Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines [Link is to the Word download – this file can also be opened with OpenOffice which is free].

(6) Case Definitions, Diagnostic Algorithms, and Priorities in Encephalitis: Consensus Statement of the International Encephalitis Consortium [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Oct;57(8):1114-28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit458. Epub 2013 Jul 15.

The above article has been cited by 78 articles in PubMed Central.

(6) Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: diagnosis and treatment [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018 Jul 9;11:1756286418785071. doi: 10.1177/1756286418785071. eCollection 2018.