In this post I link to and excerpt from Core EM‘s Feb 12, 2020 post “Pediatric Head Trauma” by Ellen Duncan, MD, PhD.

In addition, please see Core EM‘s “The Infant Scalp Score Infographic” by Ellen Duncan, MD, PhD. for infant scalp hematoma.

All that follows is excerpted from the above post.

BACKGROUND

- More than 500,000 annual emergency department visits and 60,000 hospitalizations for pediatric patients with TBI in the United States (Chen, Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018., PubMed ID: 29874782)

- Most head trauma is minor, but it is crucial to identify patients with clinically important traumatic brain injury who require further evaluation and management

- CT scans are associated with significant ionizing radiation, which may be harmful to the developing brain (Brenner, NEJM 2007, PubMed ID: 18046031)

- Always consider non-accidental trauma

CLINICAL EVALUATION

- History should include (S)AMPLE history as well as details about the trauma (mechanism) and high-risk symptoms (loss of consciousness, vomiting, headache, behavioral changes, worsening of symptoms).

- Physical exam should include a full trauma evaluation where indicated, with specific focus on GCS, mental status, and signs of skull fracture and increased ICP

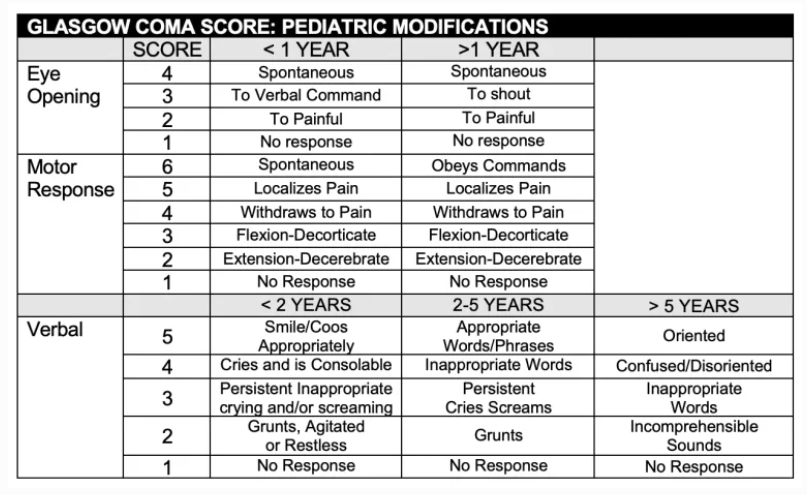

- Pediatric GCS can be difficult to assess in preverbal patients (see below)

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION

- Multiple clinical decision rules have been derived and validated to identify pediatric clinically important traumatic brain injury

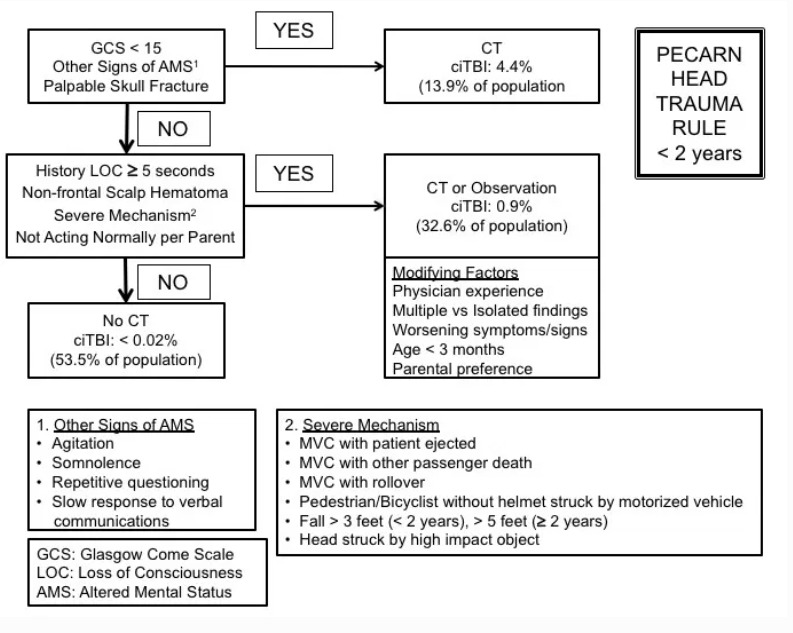

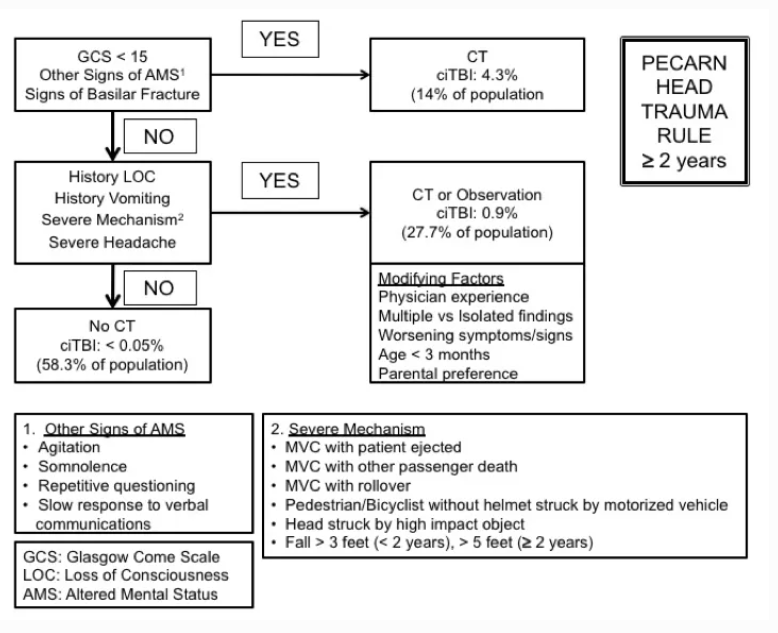

- The PECARN head trauma rule is most frequently utilized in the U.S. (Kupperman, Lancet 2009, PubMed ID: 19758692 , MD CALC)(See below)

- Patients with trivial head trauma and a GCS 14 were excluded

- In an analysis including combined age groups and both the derivation and validation sets 1 in 5,000 with clinically important traumatic brain injury could be missed (high predictive value of a negative test)

- Potential to decrease CT usage

- Rules for < 2 years and > 2 years with specific event, history and physical exam factors associated with clinically important traumatic brain injury.

- Other pediatric head trauma clinical decision tools include the Canadian CATCH rule (MD CALC) and U.K. CHALICE (MD CALC) rule.

- Recent studies suggest the rapid MRI may be an attractive alternative to CT (Ramgopol, BMC Pediatrics 2020, PubMed ID: 31931764, Sheridan, J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016, PubMed ID: 27885947).

MANAGEMENT

- ABCs take priority, as in all trauma patients

- Management includes maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion pressure, as well as addressing increased intracranial pressure (elevating head of bed, analgesics and sedation, osmotic agents)

- Anticonvulsants should be considered in patients with intracranial abnormalities (e.g. Keppra; recommended dose varies)

- Neurosurgical consult should be called for any patients with abnormal CT findings

DISPOSITION

- Most patients can be discharged after either a period of observation or after initial evaluation

- Patients with intracranial abnormalities should be managed in conjunction with neurosurgical consultants

- The CHILDA Score can be used to determine the need for ICU admission (Greenberg, JAMA Pediatrics, PubMed ID: 28192567)